ANCEZUNE duc d' (EN)

Biographical article

The son of Jacques-Louis d’Ancezune (1669–1751) and Madeleine d’Oraison (?–1750), André-Joseph d’Ancezune Cadart de Tournon d’Oraison was born in December 1695. He was the Marquis d’Ancezune, and later Duc de Caderousse upon the death of his father in 1751. In 1715, André-Joseph joined the King’s musketeers and in April of that year (Mercure galant, 1715, pp. 316–320) he married Françoise-Félicité Colbert de Torcy (1698–1749), the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Torcy (1665–1746), Minister and Secretary of State, and Catherine Félicité Arnault de Pomponne (1670–1757). The young bride had a significant dowry of 200,000 livres. Initially, the young couple lived with Jean-Baptiste Colbert, in the Hôtel de Torcy, Rue de Bourbon (present-day Rue de Lille), in Paris. In April 1716, André-Joseph was sent to Vienna, in Austria, on the orders of Regent Philippe d’Orléans (1674–1723), on a diplomatic mission for the birth of an Archduke, but he failed to fulfil his mission (Balteau, J., Barroux, M., and Prévost, M., 1936, p. 804). On 1 December 1716, he was entrusted with the command of a regiment of the King’s cuirassiers, which ended in 1721. In 1720, he became maître des campsde cavalerie. In 1733, he took over the command of the Dragoon regiment based in Caderousse. Acting under the orders of Maréchal Claude Louis Hector de Villars (1653–1734), he fought in the War for the Polish Succession and took part in the Italian expedition in Pavia, Novara, and Milan. In 1734, he was appointed maître des camps of his regiment and joined the Rhine army during the siege of Philippsburg. He was promoted to the rank of Maréchal des Camps on 1 January 1740, and subsequently resigned from his regiment. He left the army and the Court, and followed his father to Sceaux, in the company of Louise-Bénédicte de Bourbon-Condé, the Duchesse du Maine (1676–1753). In 1740, after the end of his military career, André-Joseph joined the entourage of the Duchesse du Maine at the Château de Sceaux. In 1751, as Duc de Caderousseas, he was called the Duc d’Ancezune. According to the Duc de Luynes and Saint-Simon, Françoise-Félicité, his wife, was an unattractive brunette, but well educated, lively, and extremely pious; she suffered from ill health and died on 28 April 1749, childless. André-Joseph never remarried and passed away in his mansion on the Rue de Bourbon, in Paris, on 17 October 1767 (Gazette de France, October 1767, p. 366). In his will (ADV, 1B17*, fol. 296–302), André-Joseph appointed as sole legatee his nephew Marie-Philippe-Guillaume de Gramont (1719–1800), who became the Duc de Caderousse and inherited the Parisian mansion on the Rue de Bourbon and all the property of the Duchy of Caderousse in the Vaucluse.

The collection

In November 1719, the Marquis d’Ancezune and his wife bought from Sieur Duguet land in Paris and a recently built mansion constructed by the architect Gilles de La Fontaine, of which only the attics were not completed (Constans, M., 1983, p. 68). Demolished in 1876, the mansion was located at the time on the Rue de Bourbon (now, the Rue de Lille), opposite the Hôtel de Torcy, his father-in-law’s residence. This residence was constructed with a courtyard and garden, and consisted of two identical apartments on the ground and first floor. It was in these areas that the future Duc d’Ancezune placed his collections of objets d’art, pictures, porcelain wares, and precious lacquer objects.

Very little is known about how his collection was assembled. Indeed, although is cabinet was entirely dispersed after his death in 1767, no printed catalogue was produced. Only his wife’s post-death inventories, in 1749, and his own, in December 1767 (AN, MC, AND/CXII/740), give us a comprehensive idea of this collection.

His wife Françoise-Félicité died on 27 April 1749. An inventory was subsequently drawn up as of 5 May (AN, MC, AND/I/441): it attests to rich and tasteful furnishings. In 1749, the collection already included bronze figures and pictures by the greatest masters, such as Albani, Titian, Rembrandt, and Veronese. In one of his cabinets, the Marquise d’Ancezune owned boxes, chests, red lacquer (probably Chinese) candleholders, and, on a plateau in the same lacquer, a Chinese porcelain tea service or ‘cabaret’ with a silver mount, and an East Indies pottery teapot, that is to say Yixing stoneware. There were also twelve scrolls, eight urns, and four large Chinese ‘blue-and-white’ porcelain cornet vases, as well as some Japanese porcelain objects decorated with silver. But the vast majority of the porcelain wares acquired by the Marquise came from Saxony.

It was an entirely different affair after the duke’s death in 1767. The evaluation of his collection of pictures was organised by the Sieur Colins, an Académie painter, on 14 December 1767, and it was sold on 29 February 1768 in his mansion on the Rue de Bourbon (Annonces affiches et avis divers, 18 February 1768, p. 145).

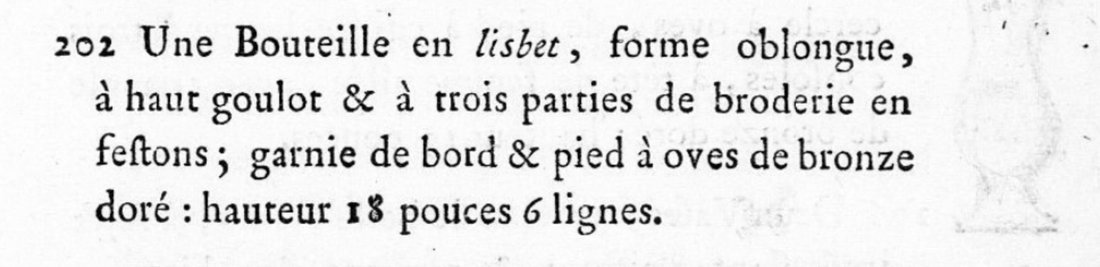

The famous marchand-mercier, or dealer, Claude-François Julliot (1727–1794), carried out the evaluation of the porcelain wares, bronzes, and lacquer objects in the collection of the late Monseigneur the Duc d’Ancezune. Hence, in the first-floor cabinet overlooking the courtyard, amidst the vases in porphyry, alabaster, and hard stones, there were tables made from precious marble and white marble sculptures, four Japanese porcelain vases with Kakiemon decorations, two birds of prey made from Arita porcelain transformed into girandoles, and several cabinets and other Japanese furniture in black lacquer or in relief (AN, MC, AND/CXII/740). But it was in the ground-floor salon that overlooked the garden, that his cabinet was truly established, comprising one hundred and sixty Far-Eastern porcelain articles. The Duc owned some Chinese porcelain objects from Dehua, celadons, and Chinese porcelain wares with a turquoise glaze. But most of his cabinet consisted of ‘blue and white’ porcelain articles from the Transition (1620–1683) and Kangxi (1662–1722) epochs, and some blue and white ceramic wares dating from the end of the seventeenth century, which came from the Japanese kilns of Arita. These works are adorned with decorations of embroidery, groves, patterns, and jasmine, and most are adorned with moulded gilt bronze or copper mounts. The Duc d’Ancezune owned several ‘blue and white’ porcelain pieces that came from the prestigious collection of Monseigneur the Grand Dauphin (1661–1711), the son of Louis XIV, including article no. 233 mentioned in the 1689 inventory (Sir Francis Watson and John Whitehead, ‘An inventory dated 1689 of the Chinese porcelain wares in the collection of the Grand Dauphin, son of Louis XIV, at Versailles’, no. 233). The article in question was ‘a large bottle in the shape of a Chinese blue and white porcelain “lisbet” vase with “embroidery” decorations, adorned at its base and neck with an egg-and-dart motif in chased and moulded gilt copper’ (AN, MC, AND/CXII/740), which was subsequently held in the collections of Louis-Marie-Augustin, the fifth Duc d’Aumont (1709–1782) (Aumont sale, 1782, lot 202). Dating from the beginning of the Kangxi (1662–1722) period, this bottle is one of the rare articles in the Duc d’Ancezune’s collection that has been identified (private collection).

Although, today, the Duc d’Ancezune’s Far-Eastern collections remain to be rediscovered, during the Enlightenment his cabinet was famous enough to feature in the catalogues of the greatest collections of the second half of the eighteenth century, as in those of Pierre-Louis-Paul Randon de Boisset (1706–1776), on 27 February 1777, and of the Duc d’Aumont, on 12 December 1782.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne