POMPADOUR marquise de (EN)

Biographical article

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson—Marquise de Pompadour, Duchesse de Ménars (near Blois), and Dame de Saint-Ouen—was born in Paris on 29 December 1721. She received an excellent education thanks to the protection of her mother’s friend, the wealthy financier Le Normand de Tournehem, and, on 9 March 1741, she married his nephew, Charles-Guillaume Le Normand d’Étiolles (1717–1799), Chevalier d’Honneur at the Presidial of Blois, then Farmer-General, for whom she bore a son, Charles-Guillaume (who died before his first birthday in 1741) and a daughter Alexandrine (1744–1754). Her ambition was to become the mistress of Louis XV (1710–1774). At first, she held a brilliant salon that was frequented by financiers, artists, and writers, and eventually she succeeded in attracting the King’s attention. On 23 April 1745, she moved into the former apartment of Madame de Mailly in the Château de Versailles and became the Marquise de Pompadour. She played a decisive role in the court. On 8 February 1756, she was appointed Dame du Palais to Queen Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768). She ruled over Louis XV and indirectly governed France for nineteen years, until her untimely death in Versailles, on 15 April 1764, at the age of forty-two. Her brother Abel-François, the Marquis de Marigny (1727–1781), inherited all her worldly goods (AN, MC/ET/LVI/113). Despite the intrigues and the libelles (pamphlets about the real or imagined debauches of the powerful) of every kind that were devoted to her, she protected the arts and literature, contributed to the foundation of the Sèvres Manufactory, and was involved in intense diplomatic activities, sometimes to the detriment of France (Petitfils, J.-C., 2014).

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

The collection

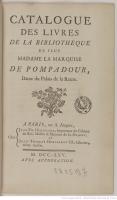

Madame de Pompadour was a woman of pronounced artistic taste. She renovated the Château de Crécy and commissioned Jean Lassurance (1690–1755) to construct the Château de Bellevue on the slope of Meudon. In 1757, she rented the Château de Champs, and, three years later, she acquired the elegant and imposing building at Ménars, on the Loire, entrusting the architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel (1698–1781) with its renovation. The Hôtel d’Évreux (now the Élysée Palace) was her Parisian residence. Upon her death, her many properties were adorned with works of art, so it was necessary to draft an post-death inventory to facilitate the inheritance and assess the value of her collections. The inventory began in June 1764 and was completed in July 1765 (AN, MC/ET/LVI113 and AN, MC/ET/LVI/114). Madame de Pompadour was a great collector of pictures, sculptures, furniture, lacquered objects, porcelain wares from France and the Far East, engraved stones, jewellery, silver and gold items, books, and prints. Only the contents of her library, which was dispersed between 3 June and 26 July 1765, were listed in a detailed printed catalogue.

Madame de Pompadour’s porcelain wares

The porcelain wares described in her post-death inventory were sought after by the marchand-mercier (dealer) Simon-Philipe Poirier (circa 1720–1785), who had a boutique on the Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris. For Madame de Pompadour the Parisian dealers were the main suppliers of Asiatic objets d’art inventoried in her residences. With her considerable wealth, she was able to purchase highly expensive objects that were very rare on the French art market. She thus accumulated almost three hundred items of Far-Eastern porcelain, for the most part adorned with gilt bronze mounts in the rocaille style. It was in the boutique of Lazare Duvaux (circa 1703–1758), her favourite dealer on the Rue Saint-Honoré, that Madame de Pompadour bought more than one hundred and fifty mounted porcelain objects. Thanks to the dealer’s journal, we know that her acquisitions of Asiatic ceramics began in April 1750 (Courajod, 1748–1758, p. 48). Up until 1752, she spent an enormous sum of money on vases, magots, and animals. Her purchases rapidly decreased until 1757. Aside from Duvaux, the Marquise was in contact with the dealer Edme-François Gersaint (1694–1750). Hence, as of 1748 and on behalf the Marquise, Gersaint purchased—during the Angran de Fonspertuis (1669–1747) auction—a large Chinese porcelain pot for 1,100 livres (auction in Paris, December 1747, lot 52). Most of the porcelain wares acquired by the Marquise came from China, and were often relatively recent. Hence, her taste seems to have focused on plain, speckled, or cracked celadon (jade) pieces, monochrome porcelain objects with a lapis lazuli ground, several rare blancs de Chine (Chinese ceramics) and marbled porcelain wares, all of which dated from the end of the seventeenth century or the first half of the eighteenth century.

The laquered objects

Highly luxurious objects, these lacquered pieces were also described and evaluated by Poirier during the post-death inventory. Madame de Pompadour owned lacquered objects of an exceptional quality, such as the large casket from the former collection of the Duchesse du Maine purchased from Duvaux, on 15 April 1753, for the sum of 5,000 livres (Courajod, 1748–1758, pp. 156–157). Bought for only 2,800 livres, it was subsequently part of the collection of the financier Randon de Boisset (1708–1776) (auction in Paris, 27 February 1777, lot 745), then that of the great English collector William Thomas Beckford (1760–1844). She owned many seventeenth-century Japanese lacquered pieces, including caskets, boxes of varying sizes, potpourri containers, vases, bottles, containers for flowers that were often fitted with gilt bronze mounts. The Marquise’s furnishings were complemented by several fine examples of Parisian cabinetmaking covered with Far-Eastern lacquered panels. These luxurious and highly expensive items of furniture, such as chests of drawers, corner cabinets, secretaires (secrétaires en armoire or à dos d’âne) veneered with oriental lacquered panels, were made by the marchand-mercier Thomas-Joachim Hébert (1687–1773). Eager to rapidly settle the question of the Marquise’s legacy (AN, MC/ET/LVI113), Madame de Pompadour’s furniture, lacquered objects, and Chinese porcelain wares were not transferred to the collection of her brother the Marquis de Marigny, with the exception of those inventoried in the Château de Ménars. They were dispersed via auctions on an almost daily basis as of November 1764 in the Hôtel d’Évreux, and the auctions continued for more than two months. At the beginning of 1766, the last lots of these auctions were finally dispersed, to the great satisfaction of major collectors, art dealers, and merchants (Cordey, 1939, pp. 263–267).

Refined taste

Given the Marquise’s reputation for good taste and high standards, the provenance of the lacquered objects, like that of the oriental ceramic objects, became an indispensable reference. This prestigious provenance was sometimes remarked on in later auctions. Attesting to her singular interest in China, Madame de Pompadour owned fifteen objects with Chinese decorations made from Sèvres porcelain by Charles-Nicolas Dodin (1734–1803). This love of wares with Chinese decorations made by the Royal Manufactory of Sèvres was of some significance because it is well known that the royal mistress had a passion for Chinese porcelain. The Asiatic objets d’art from the Marquise de Pompadour’s collection are now held in the Musée du Louvre, the Musée Nissim de Camondo, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the English royal collections, and in certain prestigious private collections.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne