KRAFFT Hugues (EN)

Biographical article

A Great Bourgeois Heir

Hugues Krafft was born on December 1, 1853 at 1, rue de Rivoli, in Paris. He was the eldest child in a wealthy bourgeois family of German origin. On June 3, 1852 in Frankfurt, his father Guillaume Hugues Krafft (1804-1877), a traveling salesman who was then a partner of Louis Roederer (1809-1870), married Maria Elisabeth Emma Mumm (1828-1880), cousin of the founder of the prestigious house of champagne. Hugues was raised in the Protestant faith and entered the small high school in Reims in 1860, the city where his family had settled in 1855 near the cellars of the Roederer establishments (SAVR, s.c.). That same year, his father acquired the Château de Toussicourt (SAVR, s.c.) in the Marne countryside. Although he was enrolled from 1865 to 1875 at the Lycée de Reims, Hugues had a chaotic schooling which was disrupted for health reasons and disrupted by numerous stays abroad and by the Franco-Prussian war: the family took refuge in Boulogne-sur-Mer. From 1873 to 1874, he perfected his English at Eton in England. On his return, he joined the French army in the 3rd engineer regiment in Arras from 1875 to 1876. He was then hired as a wine merchant by Roederer until 1877, the year of his father's death: he became the heir to an immense fortune which enabled him to live out his passions for art and travel. He then embraced the life of an heir in Paris: in 1879 in particular, he was admitted to the Cercle de l’Union artistique, which brought men of the world in contact with artists.

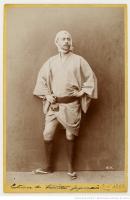

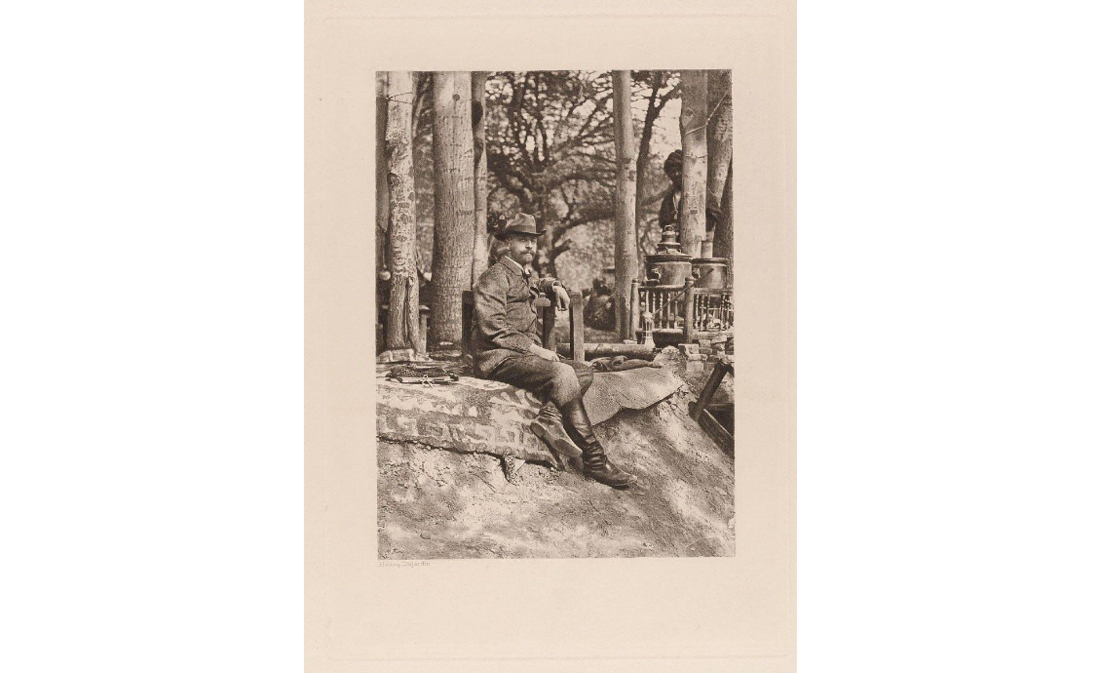

Photographer-Traveler

The year following his mother’s death in 1880, he launched a world tour with his brother, Édouard-Hermann and two friends, Louis Borchard and Charles Kessler. From October 31, 1881 to March 1883, modeling their itinerary on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne, they visited Egypt, the Indies, the island of Ceylon, Cochinchina, island of Java, China (Hong Kong, Canton, Macao, Shanghai and Beijing) and Japan and then crossed the Pacific towards the United States (Honolulu) before returning to the Old Continent. For Hugues Krafft, the highlight of the trip was Japan, which fascinated him with its landscapes as well as its civilisation. From August 13 to November 1882, he settled with his companions in Yokohama, the starting point for a journey of 1000 kilometres on the two main roads linking Tokyo to Kyoto, the Tokaido to the east and the Nakasendo to the west. The main cities on this excursion were Yokohama, the three cities of Kansai (Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe), Nagasaki, briefly, and Tokyo, the new capital. After his comrades left for North America in November 1882, Hugues extended his stay until March 22, 1883 to devote himself to making photographs and exploring. He continued his travel between Tokyo and Yokohama, visiting Nikko, Hakone, Atami, Kamakura, etc. He was a globetrotter who, throughout his life, would satisfy his passion for travel and photography (he was a member of the Société française de photographie from 1884 to 1890 and traveled with his gelatin-silver bromide glass plate camera). Subsequently, he visited Greece, Italy, Bavaria, the Maghreb (Algeria, Tunisia), Egypt, Palestine, Spain, Scotland, Austria, Bosnia, Montenegro, and Sweden. He traveled several times to all these destinations for tourist or therapeutic reasons: his fragile health forced him to take numerous cures in European spa towns, primarily German and French. He was one of the travellers who explored Central Asia under Russian domination. The first time, in May 1896, he attended the coronation of Tsar Nicolas II in Moscow accompanied by Baron Joseph Berthelot de Baye (1853-1931), an archaeologist from Champagne who was a friend. Krafft then followed him on his archaeological mission to Tatarstan, then in Siberia to Ekaterinburg in July 1896. On August 11, Krafft continued his journey alone towards Western Georgia via Kiev to the Crimea until mid-October. Two years later, he joined de Baye, who was then on an archaeological and ethnographic mission in the region, for a second journey through the southern Caucasus (the republics of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) from early October to mid-December 1898. He then journeyed to Russian Turkestan alone (republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan), which he explored for five months (visiting Samarkand, Ferghana, Tashkent, Bukhara, etc.) in 1899.

Philanthropic Protector of Heritage

Krafft naturally became a member of many heritage associations and travellers' societies, such as the Société de géographie de Paris, where he exhibited photographs embellished with Japanese objects in December 1883 and made numerous presentations such as that of April 4, 1884 (SAVR, sc) about his travel in Japan. In 1885, he became a member of the Société de géographie commerciale de Paris, where on January 15, 1884 he had given a talk about Japan. On May 19, 1890, he participated in his first dinner of the Réunion des voyageurs français which was followed by many others. He joined various circles of japonisants, such as the Société franco-japonaise de Paris in 1900, the year of its foundation: he became a life member and regularly occupied a seat on its board of directors. He also belonged to the Association française des amis de l’Orient created at the Museé Guimet in 1920. He was a member of the Société des amis des monuments parisiens from 1886 until its dissolution at the beginning of the 20th century.Beginning in 1891, he belonged to the 60-member administration committee appointed by the general council. In 1908, he joined the Société française d’archéologie and was elected to the Commission des monuments historiques on June 4, 1920, in which he was involved until 1933. Since 1890, he had been a member of the council of administration of the Union centrale des Arts décoratifs (where he was the second secretary from 1894 to 1898). There, he met the Reims scholar Ernest Kalas (1861-1928) with whom he founded the Société des amis du vieux Reims (SAVR) on February 3, 1909. The society’s headquarters were none other than the residence of Kalas, the Hotel Coquebert located at 5, rue Salin, where there was a first-floor apartment for Krafft, the founding president. The following year, he bought the hotel Le Vergeur, 1, rue du Marc, which he had to restore after the damage suffered by the German bombardments during the Great War, in order to make it his residence and the headquarters of the SAVR from 1930. This is where he died on May 10, 1935, at the age of eighty-one. He left the entire building, which since 1932 had also been a museum, to the society.

A Known and Recognised Personality

Krafft divided his time between his apartments in the northwest of Paris in the 8th, 16th and 17th arrondissements, his properties in Loges-en-Josas and Toussicourt, and his residences in Reims. In all these places, he received or was received by the literary and artistic tout Paris as well as major world figures (SAVR, s.c.). His reputation and involvement in cultural and patrimonial activities granted him much recognition and many honours: on April 30, 1886, he was appointed an officer of the Academy as a member of the Société de géographie de Paris, then on April 9, 1903, an officer of public education as a man of letters and laureate of the Institute (SAVR, sc). The Minister of Commerce elevated him to the rank of Chevalier in the ordre de la Légion d’honneur by decree of October 29, 1889, following his contribution to the Paris Exposition universelle of 1889 as exhibitor and secretary of the committee of the section on retrospective labor history (AN, 19800035/187/24381). Among his many additional decorations are the Order of Danilo I, Prince of Montenegro, in 1897 and Knight of the Order of Stanislas on September 21, 1901. In 1902, he was appointed corresponding member of the Académie nationale de Reims before being elected a full member in 1909 and becoming its annual president in 1930.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

The collection

An Enlightened Collector

Hugues Krafft's passion for collecting works of art can be explained both by his personality as an aesthete and by his family heritage. The artist Jacques-Raymond Brascassat (1804-1867) was a friend of his father, who became his patron and primary collector (Foucart P., 1887). Alongside the other European collections, Krafft inherited this collection, which he exhibited at home after donating numerous graphic or painted works to French and foreign museums (Foucart P., 1887, p. 51-52). He himself was an amateur artist whose talent was apparent in both his watercolours from Japan and his photographs, which he would sometimes color, and which remain first-class patrimonial and ethnographic documents.

An Eclectic Collection of a Traveler and Art Lover

Above all, his collection is the result of his travels and discoveries. Japan played a dominant role, while Central Asia represented a second center of interest, especially due to his trip to Turkestan. He had the passion of an ethnographer and collector of authentic folkloric works. In his writings, he admits to not giving in to the fashion for modern tourist objects adapted to the tastes of Westerners both in India and in Turkestan, where he deplored the degeneration of craftsmanship (Krafft H., 1902, p. 28). This is particularly true in Japan where he sought the preservation of traditions, often fantasised, in the midst of disappearing. He also called for the creation of “museums of indigenous decorative art – as was done in Tashkent” (Krafft H., 1902, p. 29). He made many of his purchases from reputable merchants, such as in Delhi Manik Chund at the end of December 1881: “What a lot of sessions at their house! What endless colloquies! What a lot of unpacking and haggling for the costumes ordered, for the embroideries and cashmeres chosen!...” (Krafft H., 1885, p. 43-44). In China, “Guided by his experience (M de Semallé à Pékin, bibeloteur et photographe), we have embarked on considerable purchases here […]. Thus we will take away exceptional pieces: precious furs, bronzes and old cloisonné, porcelain from good periods, silks of imperial provenance, etc.” (Krafft H., 1885, p. 240-241). In Japan, mainly in Tokyo, he purchased many objects from art dealers and antique dealers, such as lacquers, ceramics, textiles, bronzes, weapons, etc., as well as about 350 photographs, often complementary to his own shots, from the studios of Felix Beato (1832-1909), Stillefried & Andersen, Suzuki Shinichi (1835-1918) in Yokohama. In February 1883, he commissioned a traditional wooden house from a Tokyo architect to be assembled by a Japanese carpenter on the family property of Jouy-en-Josas, renamed Midori-No-Sato (the hill of fresh greenery) [Omoto, K., 2018, p. 222-237]. The 12 hectares were transformed into a Japanese garden by Japanese nationals such as Wasuke Hata (1865-1929) who even laid out a miniature garden. Inaugurated on June 19, 1886, this "corner of Japan at the gates of Paris" (Régamey F., 1891, p. 213) allowed him to receive the Parisian literary and artistic elite during tea ceremonies which he organised in the ‘pavilion of pleasure’. In 1893, he completed the ensemble by building a Moorish courtyard. From the beginning of the 20th century, he added to his notably Japanese collection, by buying objects from art dealers such as the Japanese Tadamasa Hayashi (1853-1906) or Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), as well as by auction at Drouot during the dispersal of major collections such as the sales of Hayashi (February 1903), Charles Gillot (February 1904), J. Garié (March 1906), Siegfried Bing (May 1906) and Louis Gonse (May 1924) [Collection Hugues Krafft. Objets d'art d'Orient et d'Extrême-Orient, 1925, p. 1].

A Private Exhibition Displayed Often…

The collections were presented in his various residences and more particularly in the Japanese pavilion of Midori, where Krafft placed part of his Japanese collection for his own private enjoyment as well as for sharing with japonisant friends, such asLouis Gonse (1846 -1921), Siegfried Bing, and Raymond Koechlin (1860-1931). Several of his trips were the subject of publications, such as the Souvenirs de notre tour du monde in 1885 or À travers le Turkestan russe in 1902, amply illustrated with his photographs. He also participated in exhibitions of photographs, paintings and objects brought back from his wanderings: in Brussels in 1883, in Toulouse in 1884 and in Beauvais and Antwerp in 1885. To the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris he lent 160 items, a third of which were taken from his photographs, for the ethnographic anthropology section of the retrospective exhibition of work and anthropological sciences (Exposition universelle internationale de 1889 à Paris, Catalogue général officiel : exposition rétrospective du travail et des sciences anthropologique, 1889). The most important lot was 73 wooden figurines painted and dressed in hemp or silk kimonos constituting 52 scenes of daily life in Japan in a fantasised and anthropological vision of the country. These dolls can be related to ningyo lucky charms. From June 22 to July 8, 1899, on his return from Russian Turkestan, he exhibited in the premises of the Union centrale des Arts décoratifs (UCAD) in Paris more than 500 photographs accompanied by various objects: costumes, textiles, jewellery, ceramics, brassware, folk objects, archaeological earthenware, and so on (Balmont, J., 1899, p. 237-238). For the exhibition of Muslim arts organised by the UCAD at the Marsan pavilion at the Louvre from April 21 to June 30, 1903, he lent five objects including Egyptian copper ware from the 13th and 18th centuries, a Mongol helmet from the 14th century, and a piece of 15th century Persian armour (Migeon, G., 1903). With the 1905 establishment of the Musée des Arts décoratifs at this location, exhibitions were organised in the great nave. From 1906, he participated in one featuring old Japanese fabrics. In 1911, he was one of the 24 lenders of Japanese objects at the exhibition of Inro (small compartmentalised medicine boxes that had become fashion accessories) and sword fittings. He did the same the following year for the exhibition on Japanese lacquers.

… then Donated and Dispered

During his lifetime, Krafft regularly made donations to fledgling museum institutions, often after exhibitions. A founding member of the Société des Amis du Louvre in 1897, first in December 1893 and again in January 1919 he donated a series of works from Japan to the museum: an embroidered fukusa (silk square) (EO 62), a painting of a falcon on a perch from the 17th century Kano school (EO 2432), an early 16th century painting of a "daimio squire" attributed to Mitsunobu (EO 2431), pendant of a "horseman" (EO 2433) offered by Louis Gonse (1846-1921), and two remarkable eight-leaf screens of paint on paper on a gold background by Mitsousoumi of the 17th century Tosa school (EO 61). One bronze incense burner representing a mountain of Immortals came from China in the Ming period. The entirety was transferred to the Musée Guimet between 1927 and 1928. At the end of the 1889 exhibition, he gave the 73 Japanese statuettes to the Musée de l'Homme, the first Japanese collection there. They are conserved today at the Musée du Quai-Branly in Paris in the department of Asia (no. 71.1889.142.1 to 73). In 1899, he donated most of the objects brought back from Central Asia to the Union des Arts décoratifs, the future musée des Arts décoratifs (MAD). Here works in metal including a copper ewer by metalsmith Ata Oulla dated 1874 (9104) took their place alongside textiles using the Uzbek technique of suzani embroidery (9111; 9113 to 9117) as well as an interesting mixture of contemporary and archaeological ceramics: "In the deserted grounds of Afrâsiâb, near Samarkand, one finds vases decorated with Christian crosses […].” The author brought back some of this pottery, as well as fragments of Muslim pottery from the Middle Ages, and offered them, along with enamelled earthenware from different Muslim periods, to the Musée de la Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres and to the Musée de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (Krafft H., 1902, p. 214). 57 entries can be identified today at the Musée National de la Céramique in Sèvres (no. 12924.1 to 47) out of approximately 90 fragments from the lot donated in 1899. At MAD, the set donated the same year and now conserved at the Louvre includes 57 archaeological pieces both Christian (MAD 9087) and Muslim (9088 3 or 226-651) from the site of Afrasiab, near Samarkand, or from buildings in the city whose state of degradation from earthquakes suggests that Krafft saved elements that he took from the field (Krafft H., 1902, p. 46). Up until his death, he donated to the MAD (1904, 1907, 1919, 1924, 1933) more than 200 works of all types (textiles, ceramics, furniture, brassware, weapons, etc.) in addition to the 1,300 photographs taken during his various trips. The most important donation after 1899 were the Japanese and Chinese textiles and other Japanese objects offered in 1933, among them exceptional Chinese silk costumes dating from the Qing dynasty (28822 to 25 and 38 39), complementing the complete set of armour (24035 1 to 18) from the same period, already given in 1924. Most of the Japanese textiles, not to mention seven precious fukusa, belong to the Edo period, pieces remarkable for their quality as well as their state of preservation: garments of armour incorporating silk, gold, printed animal skin (28831) and peacock feathers (28833). Alongside elements of traditional furniture such as inros or tea boxes and bladed weapons are a set of headdresses with lacquered examples of hunting caps (28844 to 47). But the masterpiece of the collection remains the palanquin (21772), exhibited in 1889 and donated in 1919, probably acquired during his trip to Japan and since 1934 deposited in the musée de la Voiture du château de Compiègne. It is an exceptional norimono, dating from the end of the 18th century, in black and gold lacquered wood with vegetal and heraldic decoration (arms of the Tokugawa family), with a wallpapered interior illustrating The Tale of Genji (Lacambre, G., 2010, p. 174-175). Partially to pay for the restoration of the Hôtel Le Vergeur, he dispersed most of his collections at the Drouot auction house on February 26 and 27, 1925, in 295 lots, 90% of which came from China and Japan (lacquers, cloisonné enamels, weapons, sculptures, textiles, ceramics, painted works…) [Collection Hugues Krafft. Objets d'art d'Orient et d'Extrême-Orient, 1925). Among the pieces noted by Raymond Koechlin in the preface to the auction catalog are a print by Sharaku, a Japanese bronze incense burner representing a horse from the 18th century, a Mosul tray from the 13th century, and a candlestick of a Rassoulide sultan from the Yemen, the latter two being among the four objects he had lent to the exhibition on Muslim arts in 1903.

Fragmented Sites of Conservation

In addition to the museum institutions previously mentioned, the hotel Le Vergeur in Reims, as the headquarters of the SAVR, was the greatest beneficiary of Hugues Krafft’s collections. In addition to the pieces from his family of German origin (furniture, graphic arts, ceramics, etc.), including the Brascassat collection of around 100 works, the museum preserves hundreds of photographic glass plates of Asian views: his own photos, as well as purchases such as the 350 images purchased in Japan. The museum's non-European works currently being compiled and analysed reflect his taste for and his travels in Japan in around twenty pieces (furniture, lacquers, prints, art objects), including furniture from the Edo period from the Tokugawa clan (a lacquered wooden foot chest no. 2006.0.81; an incense burner no. 2006.0.80.1-2; a metal flute, unnumbered). The objects brought back from his trip to Russian Turkestan figure prominently with exceptional lots of metalsmithing (ten occurrences of women's jewellery or buckle plates), textiles (fabrics, clothing, headgear, etc.), leather goods and other ethnographic objects, such as weapons or gourds generally used as tobacco boxes (2006.0.315.1-4). Furthermore, in an attempt to rescue items of patrimony, Krafft brought back shards from Samarkand: one bears the handwritten notice Bibi Khani in reference to the madrasah of Biby-Khanim of Samarkand heavily damaged by the 1897 earthquake (Krafft H., 1902, p. 46). The same is true for the Chinese collections, with two remnants (2006.0.264.1 and 2) of the faience decoration of the "Summer Palace of Yuen-Ming-Yuen in Beijing dating from the 18th century and destroyed by the allies in 1861", as notes the guide of the 1889 Exposition Universelle of Paris where Krafft exhibited them. Particular mention should be made of a cloisonné enamel vase from China (2006.0.293), statuettes in ivory (2006.0.298.1 and 2), and in wood (2006.0.255). The importance of the MAD as a sanctuary for the works of Krafft bears remembering, although the objects of Muslim art (ceramics, brassware and carpets, excepting other textiles) have been deposited at the Louvre since 2005.

Consult the collections bequeathed by Hugues Krafft here: https://musees-reims.fr/fr/musee-numerique/oeuvres-en-ligne

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne