HOSTUN Marie Joseph d' (EN)

Biographical article

The Duc de Tallard belonged to the high nobility of the court. His father had been made a Marshal of France in 1703. He was a member of the Conseil de Régence in 1717, then Minister of State in 1726. Marie Joseph became governor of Franche-Comté in 1728. On 13 March 1713, he married Marie Isabelle Gabrielle Angélique de Rohan-Soubise (1699–1754) in Versailles. They had a son in 1716, Charles Louis Joseph, Duc d’Hostun (1716–1739), who died without children. The Duchesse de Tallard was named a dame du palais of Queen Marie Leszczynska (1703–1768) in 1725, then governess to the royal children in 1732. The Duc presented his collections in his mansion on the Rue des Enfants-Rouges, in Paris, which Jean Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny (1731–1802) visited at the end of the Duc’s life; he depicted the Duc as follows: ‘A connoisseur of pictures and fine objects, he found my youthfulness appealing. Suffering from gout, he moved around in a wheelchair and was a connoisseur of everything he owned that was precious’ (Dufort de Cheverny, J.-N., 1990, p. 61). The Duc de Tallard died in his Parisian mansion, where the sale of his furniture and collections was held on 22 March 1756 and lasted until the following June (Annonces, affiches et avis divers, 18 March 1756, p. 181; 5 April 1756, p. 220; 8 April 1756, p. 228; 26 April 1756, p. 260; 10 May 1756, p. 293; 24 May 1756, p. 324; and 10 June 1756, p. 356).

CC0

The collection

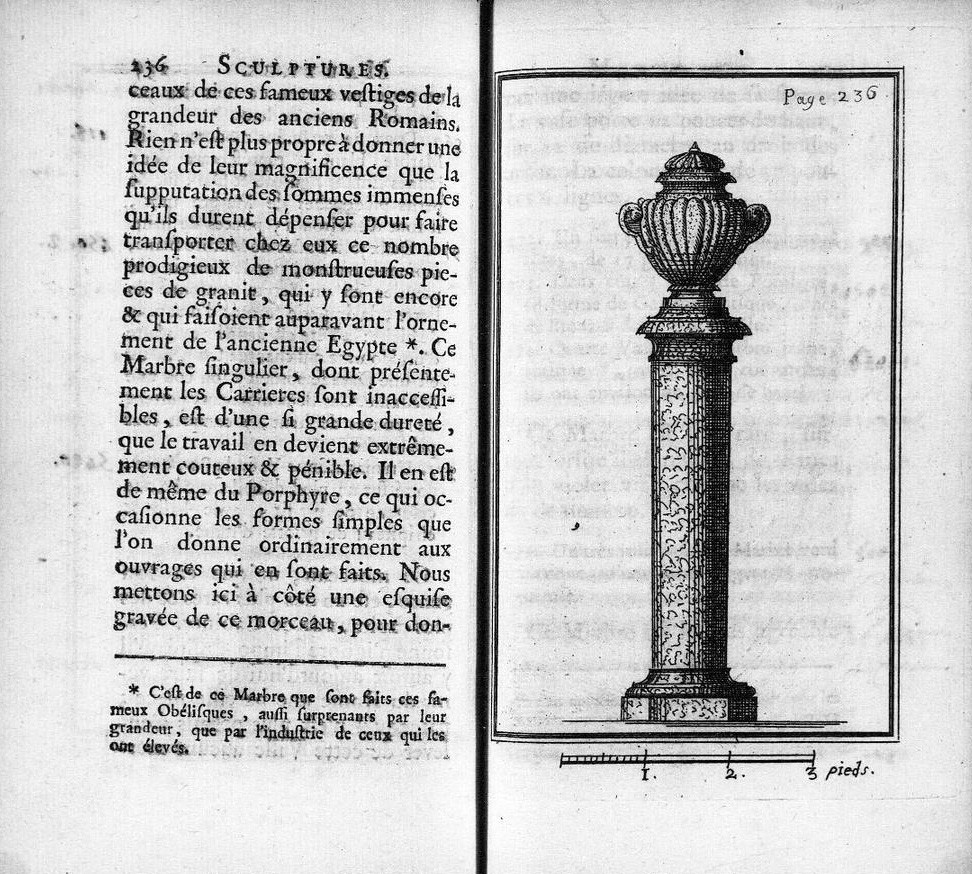

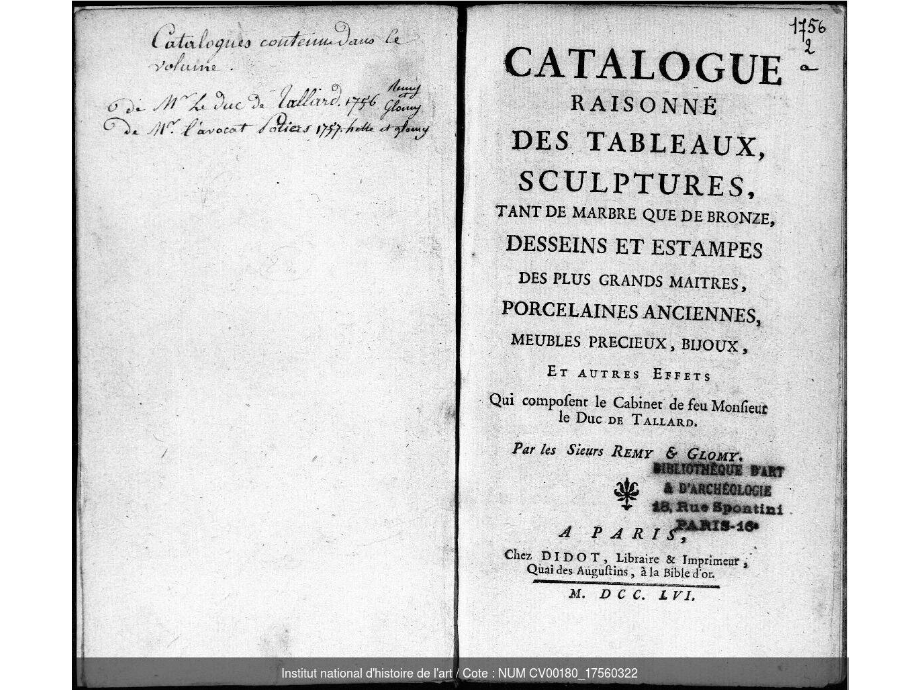

The catalogue of the post-death sale of the Duc de Tallard’s collection included 184 pictures, nine sculptures, twenty-four marble busts, 489 drawings, 232 prints, thirteen small bronzes, two busts, two bronze vases, 301 Oriental porcelains, thirty-three vases, twenty-six tables, and a granite column with a base and capital made of griotte marble, surmounted by a porphyry vase. The Duc de Tallard’s collection was known for its high quality and Rémy and Glomy, the catalogue’s authors, rated it immediately after that of the king and of the Duc d’Orléans, due to the splendid nature of the works collected in every field. The Duc focused on Italian painters (122 pictures) and the most prestigious schools such as those of Venice (four pictures), with works by Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Veronese, and Rosalba Carriera; the Bolognese school (thirty-one pictures), with Carraccio, Guido, Albani, Domenichino, and Guercio; the Roman school (twenty-nine pictures), including Perugino, Raphael, Julius Romanus, and Cortone; the Parmese school (eight pictures), with Correggio, Parmigiano, and Lanfranco; and the Florentine school (seven pictures), with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Del Sarto; these were complemented by three from the Milanese school and two from the school of Sienna. More authentically, there were nine works by masters from Genoa, Naples, and, above all, Spain, with a Ribera and seven works by Murillo. the Northern Schools (twenty-nine pictures) were represented by the most famous artists, such as Dürer, Rubens (five works), van Dyck (four works), and Rembrandt (two works). The French school was the least represented (twenty-four pictures in total), with works by seventeenth-century painters such as Poussin, Valentin, and de la Hire. The same schools were present in identical proportions in the ensembles of drawings and prints. The schools and subjects of the pictures, drawings, and prints were typical of the taste of the major connoisseurs at the end of the seventeenth century (Michel, P., 2007; Guichard, C., 2008).

As he belonged to the high nobility of the Court, the Duc de Tallard collected the works of the most prestigious painters: the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian masters, the most famous names of the Northern Schools, and the seventeenth-century French School. These major schools were considered a benchmark of taste by collectors and the Académie de Peinture, with a preference for the Bolognese, Roman, and Florentine schools. However, the large number of pictures from the Venetian School attest to the changing tastes of connoisseurs at the end of the seventeenth century and their renewed interest in colour (Michel, P., 2007; Guichard, C., 2008). Aside from Rosalba Carriera, the Duc de Tallard owned no works by contemporary painters, such as La Fosse or Boucher. This grand aristocratic taste was also evident in the subject matter, with a majority of historical subjects. With regard to the Northern School, Tallard only kept the historical or religious themes, a still life, and two landscapes, but no tavern scenes and other bambocciate (genre scenes of everyday life). The most interesting aspect was the presence of works by Spanish painters, even though the aesthetics were quite removed from academic canons. Although four pictures represented religious themes, the other three depicted a man drinking and children, subjects considered not particularly noble. Was the Duc drawn to the different atmosphere and aesthetics in Murillo’s works? The presence of bronzes and eastern porcelains was standard due to the taste for dense presentation and contrasts between materials and colours.

The composition of the collection of porcelains reflected the changing sensibilities in the first half of the eighteenth century, consisting of one third of polychrome, celestial blue, and celadon porcelains, a third of Japanese porcelains, but only one fifth of blue and white porcelains, which had been so popular in the preceding century. The presence of many vases and marble and granite tables attests to the new fashion that emerged in the middle of the eighteenth century for such pieces, inspired by ancient lapidary works (Castelluccio, S., 2013, pp. 135–146). The Duc de Tallard’s collection was in keeping with the fashions of his times, as attested by the predominance of the Italian schools and the focus on the Venetian school, as well as the many Eastern porcelains, aside from the blue and white wares. However, he did impose his own taste by collecting the works of the Spanish masters rather than going along with the fashion for the genre scenes of the Northern schools. A collector first and foremost, he was not a patron, as indicated by the absence of works by contemporary painters. However, the Duc was also a pioneering collector, as he collected marble and granite tables and vases before the vogue for neo-classicism revitalised by the discoveries made in the archaeological excavations at the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the second half of the eighteenth century. For the first time in a sale catalogue, one of the lots offered for sale was illustrated by a granite column surmounted with a porphyry vase. Although the quality of the engraving was mediocre, its presence attested to the novelty and prestige of these objects, whose success only increased over the ensuing decades. The composition of the Duc de Tallard’s collections reflected his artistic education acquired in the second half of the seventeenth century, with however a certain independence with regard to contemporary aesthetic standards, as well as his willingness to adopt new approaches to collecting, attesting to his open-mindedness.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne