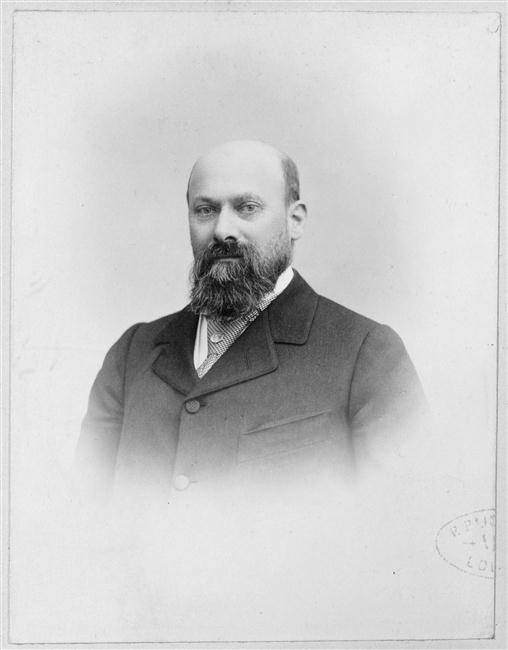

MARTEAU Georges (EN)

Biographical article

Georges Edgard Marteau was born on 21 December 1851 in Chizé, a small village in the Deux-Sèvres département (Peli, 2000–2001, pp. 4–5). The early life of the young man was marked by his father’s premature death in 1858, and by his departure for Paris in 1868 (Peli, 2000–2001, pp. 4–5). He attended the Lycée Saint-Louis and, after obtaining his baccalaureate in sciences and literature in 1871, he enrolled in 1872 at the École Centrale des Arts and Manufactures (Peli, 2000–2001, pp. 5–6). Here, he attended the course on metallurgy, followed in 1876 by a mechanic’s course, and graduated as a civil engineer that year (Peli, 2000–2001, pp. 5–6).

When he first arrived in Paris, he stayed with his uncle Baptiste Paul Grimaud, who had been a playing cards manufacturer since 1851. It was under his protective wing that Georges Marteau’s professional future was mapped out, to such an extent that it is easy to believe that his career path was carefully chosen by his shrewd and visionary uncle, who, letting no opportunity pass him by in this era of unbridled mechanisation, no doubt made the most of his nephew’s situation to benefit the latter and his industry. In 1877, as a young civil engineer, Marteau joined the firm Aubert, which specialised in manufacturing steam machines and locomotives. On 16 September 1878, in association with the engineer and mechanic Émile Gontard, he bought the Steinmetz factory and founded the firm ‘Gontard, Marteau et Cie’. The aim of the new establishment was to manufacture clasps for travel cases and construct machine tools used by binders, paper manufacturers, and wallpaper makers. Metalworking and the art of paper manufacture formed the basis for Georges Marteau’s early interest in the two materials as the supports of industrial and artistic genius. The business slackened in May 1884 and, in July of that year, Marteau became a divisional labour inspector of underage children and girls working in industry, initially based in Limoges, then in Nancy. He left this post in July 1886. On 5 December 1887, in Suresnes, he married Marguerite Seiler (1863–1899) the daughter of the director of the Cristalleries de Saint-Louis, in Moselle (AD 92, E_NUM_SUR_M1887/53). The marriage contract drawn up on this occasion mentioned no collection, and no playing cards, Japanese art, or Persian art, but did mention the existence of a library that contained ‘various scientific, artistic, and literary works’.

Several months later, on 2 July 1888, Marteau joined the company ‘Grimaud et Chartier’ as an associate. Henceforth, and for the next twenty-one years of his professional life, he devoted himself to the manufacture and sale of playing cards. The family business, professional opportunities, and Marteau’s technical interest in the manufacture of the cards and their raw materials—paper—probably motivated the birth of his collection of playing cards. This motivation emerged in 1894 in his translation of two German essays, Analyse et essais des papiers and Étude sur les papiers destinés à l’usage administrative en Prusse (Normal-Papier), and in his participation in 1906 in Henry-René d’Allemagne’s book Les Cartes à jouer du xive au xxe siècle. For the purposes of this study, Marteau allowed d’Allemagne to have complete access to his library and collection, and to reproduce many of the items. He even drafted a short article about the manufacture of playing cards in the nineteenth century. As the primary support for writing and images, paper was a vital component in constituting Marteau’s collection of cards, and it is very likely that the collector’s passion for drawings, Dürer’s engravings, Japanese prints, and Persian miniatures, reflected his interest in paper. Very soon, because they were of little interest to collectors and could be bought cheaply, Georges Marteau compiled an extraordinary collection of playing cards, complemented by envelopes, print moulds, and other documents attesting to their history. Upon his death, it included ‘856 sheets that came from 382 old and modern packs; 132 types of tarot paper; thirty reproductions of old cards; ninety-five prints relating to playing cards; sixty-nine judgements, orders, and edicts, …; 115 books about playing cards’. In 1902, the members of the association ‘Le Vieux Papier’, who, upon his invitation, came to admire the collection, were able to see a rare example of a real ‘collection, as the quality was matched by the quantity’ (Flobert, 1902).

In July 1907, Georges Marteau presented a selection of items from his collection at the Exposition Internationale du Livre, des Industries du Papier, des Journaux et de la Publicité, at the Grand Palais. The large and structured collection was arranged chronologically, and complemented by a whole library of books, judgements, advertising material, and official documents, attesting to a documentary interest, which was also evident in the many annotations Marteau placed on the boxes on which he presented his packs of cards. To compile this considerable ensemble, he obtained his supplies via an extensive network of French libraires and antique dealers, Corresponding Members, and foreign dealers, also by gradually using prints from Grimaud’s productions. While he continued, until his death, to rearrange and enrich the collection, Georges Marteau certainly devoted himself more intensely, in the first years of the twentieth century, to compiling a collection of Japanese art that comprised almost 2,000 objects, along with a significant collection of Persian art.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Japanese art

Georges Marteau seemed to take a late interest in Japanese art: he only became a member of the Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris in 1906 or 1907 and none of the works from his Japanese collection came directly from the Burty (1891) or Goncourt (1897) sales. In fact, he only joined the Société des Amis d’Art Japonais quite late; the printer Charles Gillot, the high-ranking official Edmond Taigny, the collector Alexis Rouart, the painter and engraver Henri Rivière, the dealer Siegfried Bing, and his friend Henri Vever were already members. Yet, the first documented and dated acquisitions of Japanese pieces by Georges Marteau were made in 1894 and 1898. At the sale of the Montefiore Collection, in May 1894 (Montefiore sale, 1894, 12; AN, *9DD7/20144787/17), he acquired a splendid helmet made from wrought iron, adorned with three broad mauve leaves, with a visor and neck guard made from iron with silver inlay and decorated with mauve leaves, a piece whose beauty Louis Gonse had already admired in 1883 (Gonse, L., 1883, p. 121). Four years later, he bought in London three combs or kushi from the Ernest Hart collection; all three were inlaid with mother-of-pearl, coral, and tortoiseshell, and featured floral decorations (Hart sale, 1898, 299, 301, and 316; AN, *9DD7/20144787/17). As of 1900–1902, he seemed to have started collecting objects with some intensity, made possible by the large number of major sales that followed the deaths of the first generation of collectors of Japanese art. However, that was not the main inspiration for his collection: in April and in August 1899, Marteau lost his uncle Baptiste Paul Grimaud and his wife, and consequently became the heir to and director of the playing cards factory. ‘Deeply affected by his loss, he [sought] consolation in art’ (Kœchlin, R., 1917) and he acquired large numbers of objects from the Parisian dealers Siegfried Bing and Charles Vignier, and attended most of the sales of Japanese art: Hayashi, Gillot, and Suminokura. In 1902, he acquired at the Hayashi sale several prints, including a magnificent piece by Hokusai representing a falcon near a blossomingplum tree—this was the most expensive print he acquired. He complemented it two years later with its pendant, representing two cranes on a snow-covered pine tree. In 1904, he acquired 180 objects at the two auctions of Charles Gillot collection, and thus managed to assemble half of his collection of prints and Japanese books (Gillot sale, 1904; Marteau sale, 1924; BnF, Prints, Marteau inventory, 1909). But he also bought a number of movable sabre guards called tsuba, boxes with compartments, inrō (box-like seal holders attached to a cloth sash), fuchi-kashira (‘collars’ and ‘pommel caps’), chawan (tea bowls), and miniature (netsuke) figurines. He tirelessly enriched his collection until 1913, when he bought eighteen objects at the Édouard Mène sale (Mène sale, 1913; Marteau sale, 1924). Guided by his taste and owning a library that housed works on Japanese art, in particular by Louis Gonse, Gaston Migeon, and Edmond de Goncourt, as well as Bing’s Le Japon artistique, Georges Marteau adopted an approach to collecting as a veritable connoisseur, perhaps less concerned with technicity than beauty—a beauty that led to the reproduction of his Japanese objects in monographs devoted to Japanese art and loans for the many exhibitions of Japanese or Chinese art held in Paris between 1909 and 1914 (Lambert, 1909; Verneuil, 1910; Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 1909–1914). In contrast with his collections of cards and Persian miniatures, he wrote nothing about these objects, nor did he annotate or specifically document the works. He classified them according to a system based on the objects’ materials and functions. Firstly, there were carved objects, glass articles, and ceramic wares; then the series of utensils associated with Japanese clothing, those that are worn, along with inrō, combs, netsuke, pipes, sheaths, and ojime; the graphic arts, with the katagami stencils, prints, illustrated books, drawings, and paintings; then fabrics and items of clothing; the collection was also complemented by more than 700 weapons, sabre parts, and armour (BnF, Prints, Marteau inventory, 1909; AN, *9DD7/20144787/17). Several particularly remarkable items stand out from all these objects. Acquired at the Paul Brenot sale in 1903 and having belonged to the Goncourt collection, a kodansu, or rectangular cabinet, in mura nashiji lacquer, decorated with gold lacquer and adorned with applications of mother-of-pearl, coral, and various metals, is truly remarkable due to its minuscule size and the virtuosity of its execution. Monumental in contrast, a large four-leaf screen, decorated with peonies and meadow flowers, almost entirely covered one of the walls in Marteau’s apartment. Attributed to the School of Rinpa, it came from Siegfried Bing’s collection and Marteau acquired it in 1906 for the sum—which was quite considerable at the time—of 16,500 francs (Bing sale, 1906; AN, *9DD7/20144787/17). It was perhaps one of the volumes of models printed in the nineteenth century (BnF, Prints, RÉSERVE DD-3131-4) that inspired the motif of the ex libris in his collection of Coptic and Islamic fabrics and his Persian collection (Maury, 2019, p. 17). The latter soon monopolised all his energy and took up the last ten years of his life.

Persian art

In Raymond Koechlin’s words, ‘he was soon drawn to the Muslim Orient, and the collection he compiled of Persian and Hindu miniatures, not to mention weapons and copper items, is one of the largest in Paris. He did not merely take an interest in this art; he wanted to know everything about it and his in-depth studies resulted in a book he wrote in collaboration with Monsieur Vever, which has become a reference work in the field’ (Kœchlin, R., 1917). As a natural extension of this and, like many collectors of Japanese art, Marteau became passionate about Persian art, in particular the book arts, and became an expert in the field. In the catalogue of Persian miniatures exhibited in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs from June to October 1912, Marteau and Vever dated to 1907 ‘the marked emergence of the fashion in Paris for illustrated manuscripts and the rapid assembly of the collections that can now be admired there. Over the following years, and mainly in 1908, during the Revolution that shook Persia, a large quantity of miniatures and manuscripts arrived in Europe and above all in Paris; they were of a quality that was far higher than that of the specimens that had been considered until then as the finest’ (Marteau, G., and Vever, H., 1913, pp. 6–7). The collection of Persian and Indian miniatures, bindings, manuscripts, weapons, and copper articles which Georges Marteau assembled until 1913, took precedence over his collections of cards and Japanese objects and brought together in Georges Marteau a combination of the connoisseur and the scholar. Upon the invitation of his friend Henry-René d’Allemagne and for his report on Persia (D’Allemagne, H-R., 1911), Georges Marteau drafted in 1911 an article about ‘books of miniatures’, a subject in which he had a ‘particular expertise’, according to D’Allemagne (D’Allemagne, H-R., 1911). Marteau regretted in particular that the Parisian dealers and collectors of Persian art focused on miniatures and drawings to the detriment of texts, which, according to him, amounted to concentrating on ‘the beauty of the object without paying attention to its subject matter, date, and attribution’ (D’Allemagne, H-R., 1911). The taste of the work of art, and the interest in documentation were also important considerations for Marteau, and Edgard Blochet was spot on when he saw ‘in the perfection of (the) writing, the names of the calligraphers who signed them, in their paintings and illuminated manuscripts, in the memories of the princes who leafed through their pages to admire their decorations (the only aspects) that ever interested Marteau’ (Blochet, E., 1918) in the Persian manuscripts. This is attested by the many pages of calligraphy that he collected and documented with translations, attributions, and commentaries, which are tightly packed into the margins and versos of the sheets on which they are mounted. ‘Although he did not go so far as to learn Persian, he did work with a Persian, who translated all the necessary documents’ (Koechlin, R., 1920), a certain doctor Djalil Khan, whose signature is evident in one of these albums of calligraphy compiled by Marteau. He also worked with the epigraphist Max van Berchem, who deciphered for him the Arabic inscriptions engraved on certain pieces of metal in his collection. He was also inspired by a pioneering work published by the orientalist Clément Huart in 1909, entitled Calligraphes et miniaturistes de l’Orientmusulman. In the 1910s, when the dealer Georges Demotte offered to sell the pages from a rare and very large Shahnama manuscript, Marteau immediately bought three individual pages of miniatures and a double sheet of text. He spent 40,000 francs just on the miniatures. His friend Vever also acquired seven sheets between 27 June 1913 and 29 March 1914. Subsequently, and due to a lack of available miniatures, whose export to Europe became rare around 1911–1912, Marteau added to his collection of bronzes, copper articles, weapons, ceramics, and Coptic fabrics. Hence, on 24 December 1912, he acquired from Demotte, one of his main suppliers along with the Parisian dealers Vignier and Rosenberg, five important objects: a Dervish hatchet and four sabres, including one that had belonged to Suleiman the Magnificent (AN,*9DD7/20144787/17).

Georges Marteau died on 21 September 1916. Despite the vicissitudes of the world war, which was at its apogee at the time, his collection was distributed, according to his wishes, between the Musée du Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale (post-death inventory, at the chambers of André Prudhomme, 1916). No doubt following the recommendations of Henry-René d’Allemagne, who, envious of the collection, was aware that it was invaluable, the entire collection of playing cards was added to the collections of the Département des Estampes, as were the Japanese prints and books, with the exception of fourteen engravings on Japanese woods. Two Japanese manuscripts were given to the Département des Manuscrits. The Persian book arts collection was divided between the Musée du Louvre, which received the pages of miniatures, and the Bibliothèque Nationale, which obtained the manuscripts and calligraphy albums. And the Japanese objects were added to the Louvre’s Far-Eastern collection. However, in 1945, they were transferred to the Musée Guimet, at the same time as the Indian miniatures, as the latter had been in the Louvre since 2012. Lastly, a complementary donation from his universal legatee, Ferdinand Seiler, to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in January 1917 enriched the national collections with some of Georges Marteau’s oriental textiles and (katagami) Japanese stencils. In 1924, and in 1933, two sales completed the dispersion of the remainder of the Japanese collection, consisting of almost 700 items, and the Persian collection, of which there remained only a dozen miniatures of lesser quality and a binding. One hundred and six engravings by Dürer were also auctioned at the time.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne