GOUJON DE THUISY Eugène de (EN)

Biographical article

Eugène-Marie-Joseph de Goujon de Thuisy was the son of Auguste Charlemagne Macchabée de Goujon (1788–1838) and Eulalie Charlotte Julie de Béthune-Hesdigneul (1808–1853). Although the family de Goujon de Thuisy was distinguished by its high-ranking positions in the magistrature and the army, the Marquis de Thuisy (register in the Mairie of the village of Baugy, civil registry) was not the heir to financial and cultural wealth. In 1792, his parents lost the manorial rights over their land and all their property was confiscated and sold by the state (departmental archives (AD) Marne, J 5693). Hence, Eugène de Goujon de Thuisy did not inherit a family collection.

In 1858, the Marquis de Thuisy came into a great fortune after his marriage under the regime of full community of property with Marie-Marthe-Claire Clérel de Tocqueville (1840–1907) (AD 60, 2E 30/469). She was the daughter of Édouard Clérel, the Vicomte de Tocqueville (1800–1874),and the niece of the writer Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859). Édouard de Tocqueville owned the Château de Baugy, a Louis XVI-style residence surrounded by an enormous one-hundred hectare park. In 1883, the couple and their four children moved into the Château de Baugy, following the death of Marthe’s mother.

With the help of Édouard de Tocqueville, the Marquis de Thuisy first entered diplomatic circles in 1866 (CADC, 393QO/3933). In 1875, as embassy secretary in the Department of the Americas in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was promoted to the rank of Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. However, the Marquis de Thuisy does not seem to have travelled abroad as a diplomat and therefore did not purchase objets d’art himself abroad (CADC, 393QO/3933). In 1877, he distanced himself from Parisian political life, leaving the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and took up a post at the Mairie de Baugy as a municipal councillor. He became Mayor of the commune in 1884 and General Councillor of the Oise département in 1886, posts he held until the end of his life (record of the proceedings of the municipal council of the municipality of Baugy, as of 12 June 1875). Leaving Paris enabled the Marquis de Thuisy, who was also a composer and poet, to devote himself to his creative work (CADC, 393QO/3933).

The collection

The Marquis de Thuisy assembled a collection of more than one thousand objets d’art. Although he remained attached throughout his life to his native region, he had no interest in antiquities, medals, or coins, in contrast with most of the collectors in the north of France (Ris-Paquot, O.-E., 1912). The Marquis de Thuisy was fascinated by boxes. Hence, most of his collection comprised boxes of every size, made from all kinds of materials, and both European and Eastern in origin.

The snuffboxes, bonbonnières (sweet boxes), and French porcelain portrait boxes came from the manufactories of Vincennes, Sèvres, Chantilly, and Mennecy. The Marquis de Thuisy also collected German boxes. Furthermore, the Chinese-made European boxes attest to his love of Oriental motifs. The collection of Japanese lacquer objects may be considered as one of the most complete and luxurious extra-European French collections of showcase objects. The Japanese and Chinese lacquer objects—both ancient and modern—are beautifully made. The European boxes are made from tortoiseshell or gold, chased with great skill or adorned with exquisite miniatures and diamonds. The sabre sheaths are made from shagreen and the lacquer is inlaid with mother-of-pearl and gold. In addition, although comprising mainly boxes, the Marquis de Thuisy’s collection also contained other kinds of objects, such as sabres, Japanese Noh theatre masks and netsuke.

The Marquis de Thuisy’s selection of objects for his collection were motivated by his personal sensibilities and the social role imposed by his noble title and profession. Indeed, during the time he lived in Paris, he was a well-known public figure, who took part in the most prestigious exhibitions of objets d’art at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1878, during the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Japanese lacquer boxes from the collection of the Marquis de Thuisy were exhibited in the Trocadéro alongside old lacquer objects belonging to the most important Parisian collectors (Étienne-Gallois, A.-A., 1879, p. 144). Later, in 1889, in the Trocadéro (Hoffman, H., 1889) and the Petit Palais in 1900 (L’Univers, 15 July 1900), the visitors of the Exposition Rétrospective de l’Art Français and the Exposition Universelle discovered the most remarkable porcelain objects in the Marquis de Thuisy’s collection.

The Marquis de Thuisy began to collect objets d’art at the beginning of the 1870s and ceased acquiring objects for his collection at the end of the 1880s. This chronological milestone was closely linked to his professional and political career. Indeed, the future collector joined the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1866 and was only appointed as a paid attaché in the same department in 1872 (CADC, 393QO/3933). Furthermore, the collector was deprived of the close contact he had enjoyed with Parisian artistic circles when he was elected in 1886 to the General Council of the Oise département. His main source of acquisitions was lots of objects purchased in the boutiques of the Parisian art dealers and he acquired his Noh theatre masksin the boutiques of Philippe Sichel (1839–1899) and Siegfried Bing (1838–1905). He also placed bids in the auctions held in the Hôtel Drouot between 1875 and 1886 (Bourroux, F., 2019, pp. 51–55). During public auctions, the Oise-based collector focused on the acquisition of expensive, beautifully made articles and bought objects that had been owned by aesthetes who were admired for their collections and their familiarity with Asian objets d’art. A large Sèvres porcelain cup from M. Fournier was added to the collection of the Marquis de Thuisy in 1885 (sale of the M. Fournier Collection, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, from 2 to 6 March 1885). For almost forty years, Fournier had a shop in the Faubourg Montmartre,‘visited by everybody who was anybody in the world of curiosities in Paris’ (Eudel, P., 1886, p. 253). The major collectors of Far-Eastern objects came to the collector’s shop to buy their articles from a seller known for his honesty and objectivity. However, unlike many collectors of Asian art, the Marquis de Thuisy did not enrich his collection with acquisitions from the posthumous auctions of famous collectors of Oriental art, such as Philippe Burty (1830–1890) in 1891, Octave du Sartel (1823–1894) in 1894, and Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896) in 1897. He did not attend these posthumous auctions and it seems that the collector never bought items at these auctions even via intermediaries (Bourroux, F., 2019, pp. 37–40).

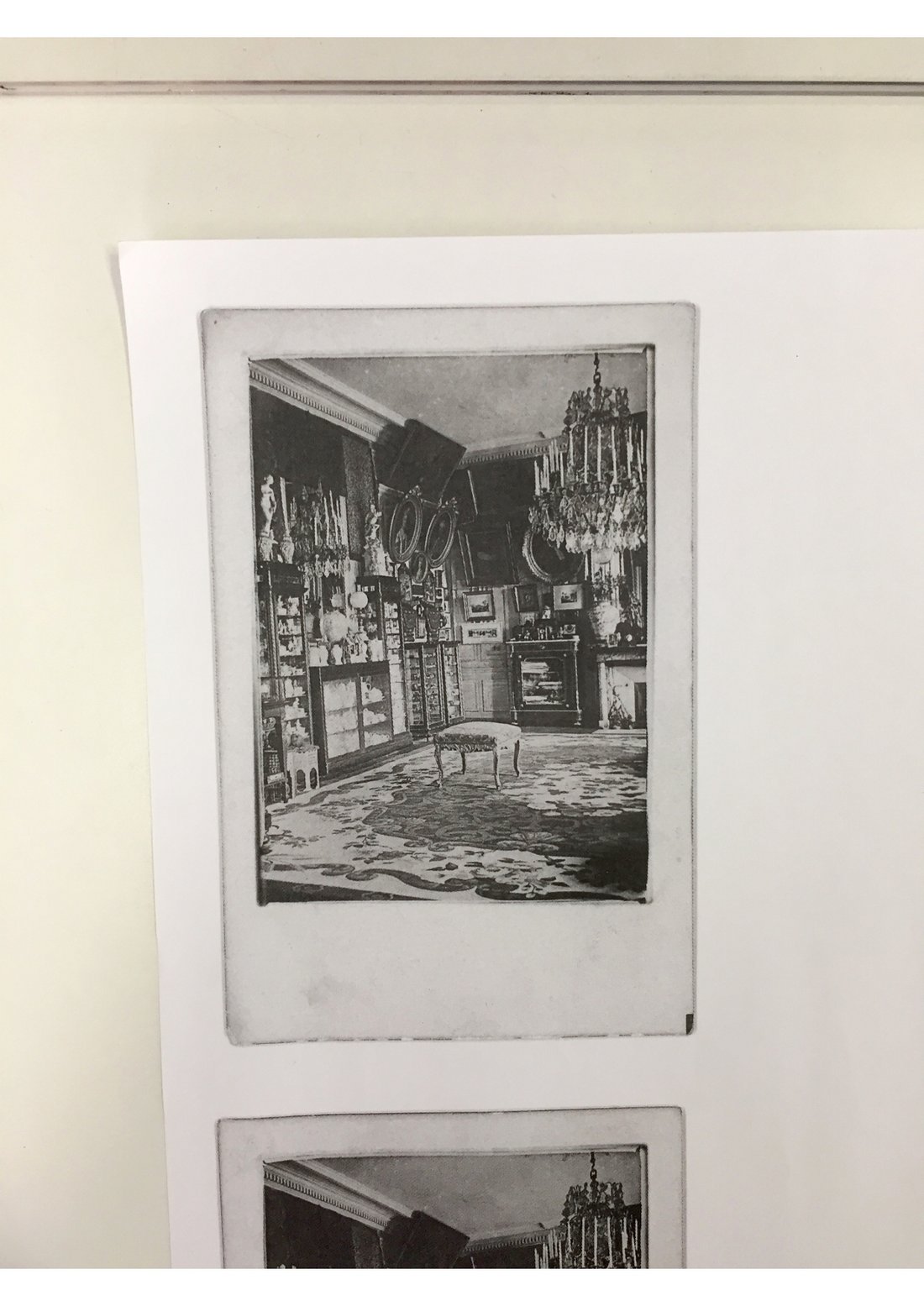

The Marquis de Thuisy’s collection was exhibited in his Parisian apartment and in the rooms of the Château de Baugy. Hence, the collector was surrounded by his objects and they were part of his daily life. A photograph of the salon of the Château de Baugy shows that it was lined with showcases, in which objects of various origins were presented: Japanese lacquer boxes alongside European porcelain boxes.

The Marquis de Thuisy also frequented auction houses as a seller. He sold a significant portion of his collection on three occasions. In 1901, he sold one hundred and fifty-eight European porcelain boxes (Catalogue des objects de vitrine […] composant la collection de M. le marquis de Thuisy, room 6, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Maître Paul Chavallier, 30–31 May 1901). In 1902, he sold French and German faience and porcelain articles, and Chinese and Japanese ceramic objects (Catalogue des anciennes faïences et porcelaines, faïences françaises, hollandaises, etc., porcelaines de Vincennes […] dépendant de la collection de M. le marquis de Thuisy, room 7, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Maître Paul Chevallier, 19 December 1902). The 1903 auction comprised exclusively Oriental objects (Catalogue des objects de curiosité chinois, japonais et orientaux, émaux cloisonnés et peints, laques de Peking et du Japan, objects divers européens […] provenant des collections de M. the marquis de Thuisy, room 10, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Maître Paul Chevallier, 27 February 1903). Apart from generating income and clearing space in his residence, the Marquis de Thuisy scaled down his collection before the end of his life in in the hope of finding the perfect equilibrium between the different types of objects it comprised. Indeed, the reorganisation of his collection right at the beginning of the twentieth century enabled the collector to make the ideal bequest. Likewise, the last sale of objects from the Marquis de Thuisy was the posthumous auction held in 1913 (Catalogue desobjets d’artet d’ameublement, porcelaines tendres […], objects de vitrine, armes orientales, tenture, meubles don’t la ventre [aura lieu] après décès de Monsieur le marquis de Thuisy, Château de Baugy, Baugy, Oise, Maître Wilhélem, 12 and 13 June 1913). When his will was drafted in 1912, he arranged for the sale of seventeen Eastern weapons during his posthumous auction (AD 60, 2 E 30/779 1911). They were probably selected from the three hundred weapons that were added to the collections of the Musée Antoine Vivenel in 1913 and those less worthy of being added to a museum collection (AD 60, 2 E 30/779 1911).

The Marquis de Thuisy drafted his will with the help of his notary in Compiègne in 1912 (AD 60, 2 E 30/779 1911). He decided to bequeath most of his collection to three museums: the Musée Antoine Vivenel, the Musée du Louvre, and the Musée Carnavalet. Stipulated in the testamentary dispositions, each donation consisted of a coherent collection of objets d’art with similar origins or subjects. The Musée Antoine Vivenel in Compiègne was attribute a lot of 1,095 decorative and luxurious objets d’art. These included lacquer boxes, weapons, carved wooden objects, and bronze articles of various origins (Chinese, Japanese, Persian, Indian, Siamese, and Cochin Chinese). There were also eighty-five boxes and soft-porcelain snuffboxes produced in the largest French and European manufactories, such as Sèvres. The Musée Carnavalet, devoted to the history of the city of Paris, has a collection of thirty-four boxes illustrating the pre-Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary periods. Lastly, the value of the bequest made to the Musée du Louvre was particularly high. It was a lot of four French and German eighteenth-century porcelain boxes decorated with exceptional materials, such as mother-of-pearl, gold, tortoiseshell, and precious stones (Study and Documentation Department, Musée du Louvre, in the department of objets d’art, descriptions of the objets d’art, nos. OA–6687 to OA–6690). Thanks to informed decisions, the collector ensured that after his death his objects would benefit from the most favourable conditions for their conservation and exhibition.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne