TARN Pauline (EN)

A poetess marked by mysticism

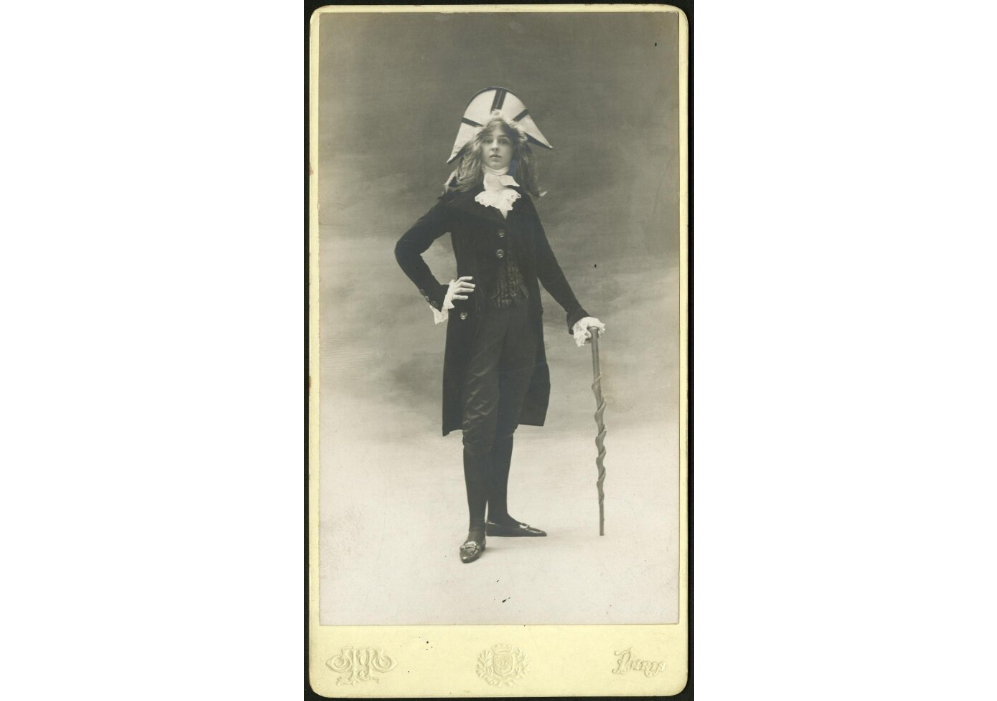

Pauline Tarn was born 11 June 1877 in London into bourgeois social context, from the union of John Tarn and Mary Gillet Bennett. John Tarn’s inheritance allowed the family to live free from want. A year after Pauline was born, the Tarn family moved to Paris. On 26 May 1881, Harriet Antoinette Tarn, Pauline’s little sister, was born. Pauline Tarn benefited from a complete education which included learning to play the piano, which would enkindle in her lifelong passion for music. It was during her childhood that she met her neighbours, Violette and Mary Shillito (BNF, NAF 26580, f.13). Violette and Pauline became very close friends with Violette having quite an influence on Pauline. Whilst Pauline seemed to be living a peaceful childhood, her father died abruptly 10 October 1886. This was a profoundly painful event for Pauline. At this time, she was forced to return to live in England, for which she had little affection (BNF, NAF 26580, f.8). When she reached the age of twenty-one, thereby becoming a major, she decided to return to Paris to live and to get back in touch with Violette. The two friends spent most of their time together, developing very strong ties. This first year back in in Paris represented “perhaps the only happy year of her life” (Germain A., 1917, p. 25). In November of 1899, by the intermediary of Violette, Pauline met Natalie Clifford Barney, who was aware of the two friends’ penchant for writing. Pauline and Natalie immediately fell in love, beginning a relationship from early 1900 and moved in together in January of 1901. The year 1901 also saw the publication of Pauline Tarn’s first collection of poems <i>Etudes et Préludes</i> which she wrote under the pseudonym of R. Vivien. On 8 April 1901, Violette Shillito died after contracting typhoid fever. Pauline was devasted by this even from which she would never fully recover. In addition to this, the first of a long series of breakups with Natalie followed, after which Pauline attempted suicide. On 1st November 1901, Pauline settled in to the ground floor of 23, avenue du Bois de Boulogne to live a solitary life. At the end of 1901, she entered into a relationship with Hélène de Zuylen de Nyevelt. The relationship with this Rothschild heiress – fourteen years her senior and the wife of a wealthy baron - provided Pauline with a modicum of stability. Beginning in 1902, she began a period of intense writing under the pseudonym of Renée Vivien. It was from this year that she began her many travels - during which she wrote a great deal – which would henceforth mark the rhythm of her live. She travelled often to Germany, Austria and the Netherlands with Hélène, who owned many properties. She went many times to Nice where she rented a villa. In 1905, Pauline Tarn carried her fascination for Sapho to the by traveling to Mytilene. Along the way, she stopped over in Constantinople to meet Kérimé Turkhan-Pacha, a Turkish admirer of hers with whom she had maintained an epistolary relationship from 1904 to 1908. From 1906 on, Pauline was feeling increasingly alone following the distancing from Hélène, the moving away of her friend and corrector Charles-Brun, and a quarrel with the painter Lévy-Dhurmer, illustrator of most of her publications. This is when she found comfort with her sister and her husband, captain Francis Alston, while developing a friendship with her neighbour, Colette. When she was not travelling, Pauline organised evenings in her Paris flat, bringing together a few acquaintances to compensate for the distance that had intervened with her close friends. Among the invited guests, were notably the orientalist Eugène Ledrain, Colette, Willy – the husband and then ex-husband of the latter - Léon Hamel, Louise Faure-Favier and Marcelle Tinayre. During these parties, Pauline refused nourishment and sinking faster and faster into alcoholism, which she even began consuming in secret. This marked the beginning of her gradual withdrawal into herself; during the last two year of her life, she had practically ceased travelling. Over the course of the summer of 1908, she again attempted suicide, this time overdosing on laudanum. During the year 1909, Pauline’s health continued to deteriorate - Hélène returned to her side. In the morning of 18 November 1909, Pauline Mary Tarn died in her Paris flat. Though everyone pretended she had died of a pulmonary oedema, after catching cold in England, Pierre Louÿs affirmed that she was suffering from polyneuritis caused by her alcoholism. This led to a false diagnosis as to the cause of a pulmonary infection from which she died three days later (Un Passant, 1910, p. 865). According to Marcelle Tinayre “her death went almost unnoticed. There was no press release, no announcements. Only four or five of her friends were informed by telegram (Tinayre M., 1910, p. 3). The photographs and writings of Pauline’s contemporaries reveal her personality, marked by mysticism. She was always dressed in dark outfits and lived a very discreet life, preferring writing to socialite dinners. She dedicated herself, moreover, to her work, publishing between 1901 and 1909 no less than twenty-five volumes, under the pseudonym of Renée Vivien, to protect her anonymity, preferring that all glory should go to her work and not her person. Through her writings – for the most part poems in verse but also texts in prose - she divulged her feelings, namely for Natalie, present in a great deal of her work. This work of writing coupled with her many travels enabled her to flee the world around her, in which she did not feel she had her place.

A collection at the service of an inner world

Pauline Tarn’s last will and testament was never found and her name is not present in the Nominative file of estates declared to the Archives de Paris (AP, DQ7 13168). No document was found concerning the arrival in 1909 of sixty-one musical instruments belonging to Pauline which are in the collections of the Musée instrumental du Conservatoire national supérieur de musique (Getreau F., 1996, p. 301). However, the seventy-seven pieces accepted in 1909 by the Musée Cernuschi benefit from better documentation. In a letter by Eugène Ledrain – a friend of Pauline Tarn and curator of the department of Oriental Antiquities orientales in the Musée du Louvre – addressed to Henri d’Ardenne de Tizac, then curator of the Musée Cernuschi, it is mentioned that Pauline Tarn left “two beautiful Buddhas to museums without specifying which museums”. Given the Far-eastern origin of most of the objects she wished to bequeath, the Musée Cernuschi seems the best adapted to accept such a bequest (note 129 p.23). On 20 December 1909, the head inspector of the city of Paris authorised the transfer of the works bequeathed by Pauline Tarn to the reserves of the Musée Cernuschi (Musée Cernuschi, Tarn Donation, letter of the chief Inspector of Beaux-Arts of the city of Paris dated 20 December 1909). The entry into the collections of the museum, occurred exceptionally before the administrative formalities relating to the donation were completed because the flat had to be rented again. In addition, “visitors were coming and taking possession of whatever pleased them as souvenir” (Musée Cernuschi, Tarn Donation, rough draft of a letter from Henri d’Ardenne de Tizac to Monsieur Verrat dated 18 December 1909), rendering the situation even more urgent. The official acceptance of these works took place during the Conseil Municipal of 18 March 1910. It was drawn up inn the form of a donation on the part of the executor of her will, Madame Antoinette Alston, Pauline’s sister (AP, 3115 W2, Don Tarn). As for the remainder, it seems that Pauline’s family may have also taken a few objects of oriental origin such as Chinese jades, bronzes, Japanese etchings but also toiletry items and jewellery. Hélène de Zuylen, a probably picked up all the correspondence as well as Pauline’s personal and literary papers, as evidently the family never collected them.

The sixty-one instruments now held by the Philharmonic bear the inventory numbers of E.1744 to E. 1805. The arrival of these instruments in the collection of the Musée Instrumental was a significant addition to towards the development of the ethnological aspect of its collections, which were hardly taken into account since the opening of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1878, which is first in line to receive this sort of collection. The study of this collection of instruments demonstrates Pauline’s taste for instruments of Asian origin, which represent half of the entire bequest. Among these, the Japanese instruments seemed to be the most appreciate by their former owner, representant 40% of the Asian instruments in the bequest.

The works kept in the Musée Cernuschi are inventoried according to the seventy-seven numbers running from M.C. 5169 to M.C. 5245138. In a letter addressed to the Chief Inspector of the Beaux-Arts of the city of Paris, from Ardenne de Tizac explains that these works came to enrich the collections of the Musée Cernuschi by endowing it with beautiful pieces of sculpted wood and by expanding the museum’s collection of religious art, facing the growing interest in oriental religions in the West (Musée Cernuschi, Tarn Donation). The summary statement of the collections, written by Henri d’Ardenne de Tizac prior to their entry into the museum, divides the works into six categories: “Pagodas, Vitrine, Cabinets”, “religious statues”, “Buddhist ex-voto”, “religious accessories”, “diverse pieces” and “Muslim art” (Musée Cernuschi, Tarn Donation). It attests to the predominantly religious character of the collection, in particular those pieces linked to Japanese Buddhism. The centrepieces of the Pauline’s collection seem to have been the Buddhas and the musical instruments, the only pieces that stayed in place in the changing décor of her appartement. Colette affirms: “Except for a few Buddhas and the instruments in the music room, all the furnishings at Renée Vivien’s place were constantly being mysteriously moved about. A collection of gold Persian coins yielded its place to jades, to which were substituted a collection of rare butterflies and insects” (Colette, 1991, p. 598). If some pieces in Pauline’s collection were only passing through her flat, they reflected her taste for the Orient, and Japan in particular. It is also interesting to note the presence of pieces of Islamic art, like elements of the décor, the interest in this art was shared by a number of collectors of Asian art in that period, as attest for example Pierre Loti’s collections and interiors. Despite the lack of certain sources with regard to the constitution of the collection, Pauline’s taste for all things Japanese may be explained by the context of the period. Japonism was gradually spreading through the various strata of Parisian society following the opening of Japan to the rest of the world in 1868 and to the simultaneous development of universal exhibitions in the West, which enabled Europeans to discover Japanese culture. The gilt bronze Bodhisattva dated to the reign of Yongle (Musée Cernuschi; inventory number M.C 5173) remains the centrepiece of her collection. It is also the only piece for which the origin is known thus far. It figures in the catalogue of a sale that took place at Drouot in 1904 (Deshayes E. et Deniker J., 1904, not paginated). Pauline Tarn had been able to start building her collection as soon as she settled into the flat at 23, Avenue du Bois de Boulogne. However, it is interesting to note that the moment Pauline found herself increasingly alone, towards 1906, coincided with the moment she became increasingly interested in the Orient (Vivien R. presented by Goujon J-P., 1986, p. 15) and that Colette described her as driven by a purchasing frensy, intent on buying another Buddha every day (Colette, 1991, p. 605). Indeed, Pauline envisaged Japan as an ideal. Certain details, like a letter addressed to Colette from Yokohama in 1907, seem to attest to a voyage of Pauline’s to Japan, undertaken during another longer voyage to Hawaii in the company of her mother. Several sources also affirm that Pauline brought back works directly from Japan. D’Ardenne de Tizac addressed a rough draft of a letter to Antoinette Alston, the executor of Pauline’s will Pauline Tarn, in which he suggested that she write to the Prefect of the Seine and to the President of the Municipal Council, to offer to the city of Paris the collection her sister had “formed over the course of her voyages to the Far east” (Musée Cernuschi, Tarn Donation). Furthermore, Louise Faure-Favier affirms that Pauline brought back “picturesque souvenirs” from her trips. However, Pauline’s very busy schedule and the time required for undertaking such a trip – a minimum of three months – does not seem to leave open the possibility that she ever actually went there. Paulin’s mythomaniac tendencies towards the end of her life only serve to further this hypothesis (Maucuer M., 2003, p. 267). Despite everything, it is certain that she drew inspiration from what they evoked in her more than their reality, to create a unique universe in which she could find the tranquillity she was seeking, far from the world and from the reality surrounding her. She created a dark atmosphere in her flat, illuminated only by candles, thereby enabling her to create a very particular staging of her collection. Her contemporaries describe her interior as funerial (Willy, 1909, not paginated). It was intimately linked to her personality and allowed her to give herself up to a cult, inspired by Buddhism, in which she made offerings to her Buddhas, but in reality, was operating around a unique and personal pantheon, put together by herself for herself.

It is in the L'Être Double (The Double Being) and Netsuke - both published 1904 and written with Hélène de Zuylen under the pseudonym Paule Riversdale - that Pauline drew the most inspiration from the imaginary Japan she created. In Netsuke, Japan strictly speaking does not appear. Pauline is inspired much more by her personal pantheon than by the actual Japan, placing her story at the heart of the imaginary world she created. In L’Etre double, Pauline also allows herself complete liberty with regard to Buddhist tradition, creating a mythology and a symbolism here again totally fantastic and personal (Maucuer M., 2003, p. 265-273).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne