BOUCHER François (EN)

Training

Born in Paris on 29 Septembre 1703, François Boucher probably did his apprenticeship under his father, Master Painter at the Académie de Saint-Luc. After a brief time in the workshop of François Lemoyne (1688-1737) and most certainly under Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752), he placed his talents as engraver at the service of Jean-François Cars (1661-1738) for the creation of frontispieces and theses. In 1722, he began a collaboration with Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766) which continued for a number of years. Here, he made over a hundred etchings based on drawings by Watteau for publication in the collection Figures de Differents Caracteres, published in 1726. At the age of 20, he was awarded First Prize by the Académie royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. However, he never received the grant money for his stay in Rome. Five years later, he finally decided to go to the Eternal City at his own expense, alongside Carle, Louis-Michel and François Vanloo (1708-1732). During his Roman sojourn – which lasted three years– he attended the classes delivered by the Académie and produced little paintings in the Flemish manner. Boucher had familiarised himself with northern painting styles by frequently visiting Parisians collections prior to his departure for Rome, where he further enriched his visual culture by studying the Italian artists.

Return to the Paris scene

In 1731, as soon as he returned, he participated in the publication of the second book of the Diverses Figures Chinoises peintes par Watteau…au Château de la Muette (Diverse Chinese figures painted by Watteau… at the Chateau of La Muette) for which he engraved twelve etchings. This was the painter’s initial incursion into chinoiserie and was certainly a decisive step in his developing attraction for the Orient. Aware of the reality of the market, in the 1730s François Boucher began implementing a commercial strategy to become the undisputed leading painter in the capital. To achieve this, he produed a series of large format paintings that would sealed his reputation, which he exhibited at the home of lawyer François Derbais (notably Aurore and Céphale (Nancy, MBA); Venus asking Vulcan to lay down his arms for Aeneas (Musée du Louvre). That same year, he was accepted as a history painter by the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture and thanks to his presentation of Renaud and Armide (Musée du Louvre), on 30 January 1734. His first official commission came in 1735 (four Virtues in grisaille, for the ceiling of the Queen’s Bedroom in Versailles). Many more would follow: the Leopard hunt in 1736, followed by the Crocodile hunt in 1738-39, both for the gallery of the petits appartements du roi (private apartments) in Versailles, four pastorals for the petits appartements du roi in Fontainebleau, fifteen painting for the Château de Choisy begun in 1741, works for the Château de Marly, etc. The 1740s were synonymous with success for François Boucher, who became one of the most admired painters of his generation, becoming the protégé of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764). His works touched upon every domain of the arts. He designed costumes for the Académie de musique, offered models for the decorative arts in collaboration with the manufactures of Vincennes, Beauvais and finally Les Gobelins, of which he became the inspector in 1755. His equally brilliant academic career lead to a professorship at the Académie in 1737, where he was appointed director in 1765. That same year, he was also appointed First Painter to the King, replacing Carle Vanloo. He died 30 May 1770 in his apartment in the Louvre Palace.

China, “one of the provinces of the rococo”

From 1740 onward François Boucher played an active role in the asiatica circuit, notably through his close ties with the marchand-mercier (merchant of objets d’art) Edme-François Gersaint (1694-1750), but most certainly also by simultaneously beginning an important collection. Though he never painted an easel painting in the Chinese manner, Boucher’s interest in oriental objects can be seen in the series of drawings intended for engraving and even etchings – which he did himself – bringing to life statuettes and painted human figures on porcelains or the Chinese etchings in his cabinet. Thus, Chinese objects appear as little touches in a few of his paintings of intimate subjects, in a number of his engravings and with dazzling effect in his sketches for the Seconde tenture chinoise (series of 6 tapestries). Boucher had a sensual relationship with the object, revelling in rendering materials, the velvety appearance of porcelain, the magnificent sheen of bronze pieces, brings to life his statuettes in unbaked clay, in a demonstration of his excellent knowledge of objects from the Far East. His “tableaux de mode” (costume paintings), placing scenes of female characters or families in sumptuous contemporary interiors, decorated with pagodas, richly mounted potpourri bowls and screens, participate in the promotion of objects one found in the boutiques of the merciers. However, certainly the most emblematic chinoiseries works is the series of ten little cartoons (Besançon, MBAA, D.843.1.1; D.843.1.2; D.843.1.3; D.843.1.4; D.843.1.5; D.843.1.6; D.843.1.7; D.843.1.8; D.843.1.9; 983.19.1) for the Seconde tenture chinoise commissioned by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) circa 1742. For half a century, several researchers have focused on revealing the visual sources Boucher used. If it has long since been established that Boucher relied upon stories recounted by European travellers such as the one of Arnoldus Montanus (1625-1683). As Perrin Stein more recently demonstrated (1996, 2007, 2019), Boucher also relied on Chinese motifs, which he isolated and freely interpreted in the drawings he did for engraving and that were very early on used in the decorative European arts (furniture, ceramics, snuff and toilette boxes). His sources were diverse: terracotta or stone statuettes, porcelains and etchings; the Gengzhi tu耕織圖 (treatise on rice cultivation and silkworm farming published in China in 1696) and the romance of the Pavillon de l’Ouest, in Chinese, Xixiang ji, 西廂記, for example served as a model for several Scènes de la vie chinoise. The painter not only removed and isolated the motifs of certain Chinese plates, he also demonstrated the serious attention he paid to the construction of space and to perspective in his Chinese-inspired works. Thus, in some of the etchings of Scènes de la vie chinoise the way he treated space drew inspiration directly from China (in particular, the angled views of barriers and guardrails).

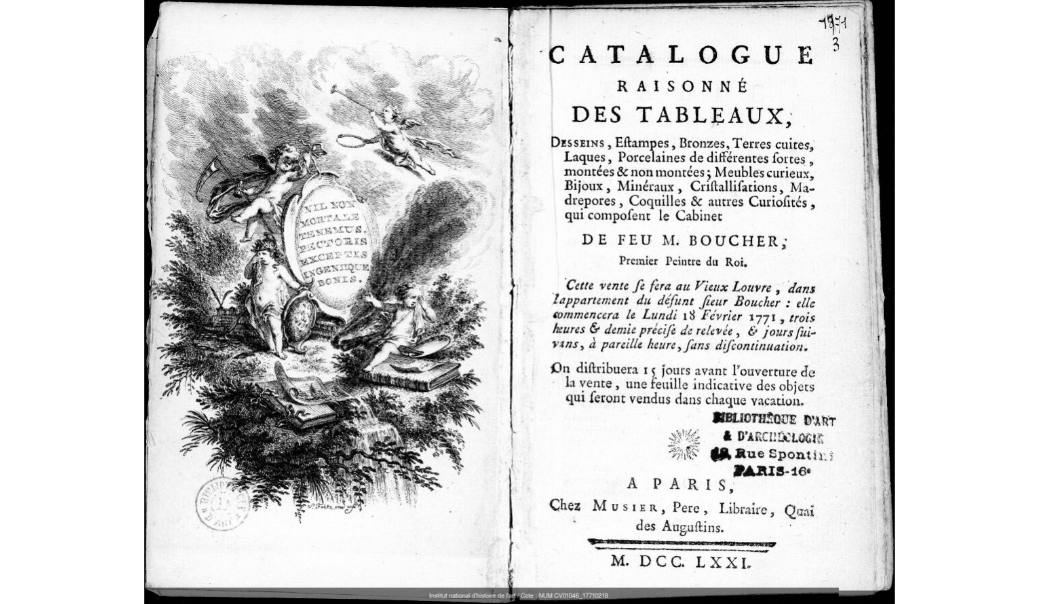

Constitution de la collection

A bulimic collector if there ever was one, François Boucher – also a recognised expert on shells – developed his art throughout his life in a world filled with works of art, oriental objects and naturalia. The collection of oriental objects François Boucher undoubtedly began building in the 1730s-1740s, was put up for sale in the painter’s apartment in the Louvre Palace from Monday 18 February 1771, ten months after his death. The catalogue prepared by Pierre Remy is the most important source for knowledge and study of this collection in the absence of an inventory after death. Recent research (Joulie F., 2017; Une des provinces du rococo: La Chine rêvée de François Boucher, 2019) has identified three objects that most probably belonged to Boucher: a pair of celadon porcelain vases in gilt bronze mounts with tritons and a stoneware potpourri bowl (called “porcelaine truitée” (flecked porcelain) in the catalogue) with gilt bronze mount with satyrs’ heads (all three held in private collections). Though nothing is known about the way his collection was displayed prior to 1756 – date of Boucher’s installation in the apartment of Charles Antoine Coypel (1694-1752) in the Louvre – the major refurbishing work Boucher undertook at that time is documented. Furthermore, the testimony of a young Savoyard aristocrat, Joseph Henry Costa de Beauregard (1752-1824), passing through Paris, written on 10 January 1767 informs us about the way the collection was displayed. The oriental objects were mixed in with natural curiosities (all kinds of stones, butterflies from India and China, four or five very small birds, an infinite number of the most beautiful minerals, corals, marine plants and petrified specimens).

François Boucher’s first purchases were undoubtedly made from the merchant Gersaint – who in 1737 decided to convert his activity to the sale of objects from the Far East – and participated in the development in Paris of the taste for Chinese objects. The painter took part in this activity by drawing the merchant’s address card and, thanks to his practice of collector, entered the circle of curious amateurs, maintaining ties notably with Jean de Jullienne, Blondel d’Azincourt (1695-1776) and Randon de Boisset (1708-1776), with whom he attended public auctions. The annotated catalogues reveals that he bought in particular during the estate sales of Antoine de La Roque (1672-1744) in 1745, René-Louis Bailly in 1766 and Madame Dubois-Jourdain (?). In addition to Gersaint, he bought from the marchands-merciers Lazare Duvaux (1703-1758), Pierre Remy (1715 or 1716-1797), Dubuisson, Rouveau and Simon-Philippe Poirier (circa 1720-1785). Truly an activity of sociability, his collection was instrumental in raising his social status. He not only acquired oriental objects. From the 1730s on, he began to discreetly and delicately include porcelains and screens in his paintings of interiors, participating in the promotion of this newly developed taste being tested by his friend Gersaint. Though the Chinese objects disappeared fairly quickly from his paintings, his collection does not seem to have been limited to a phenomenon of fashion. For the painter it was a genuine passion that lasted until his death, as attested by the number of purchases that he made, at least until 1767.

An insatiable amateur, he assembled a highly diverse collection of oriental objects which was considered “by the admission of everyone, as one of the richest & most agreeable collections one may see in Paris” as Pierre Remy emphasised in the foreword of the catalogue for the estate sale. This book is divided into four major domains: Paintings, “drawings, etchings”, diverse objects and “Minerals, Crystallisations, Madrepores, Shells & other Curiosities”. The seven-hundred-one some odd Far-Eastern objects are distributed into three-hundred-five lots, themselves broken out into ten categories, according to their material (“Bronzes, Ivories, Pagodas made of India pastes, Soapstone, silver Curiosities, Lacquers, Porcelains, India clay”) or their typology (“Chinese paintings, Curious pieces and curious Effects”). The copy held in the library of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art is the one which, to our knowledge, is the most richly annotated. It specifies the name of most of the buyers and the prices of the lots, while also detailing the presence of numerous dealers (Doyen, Dufrêne, Claude-François Julliot (1727-1794), Legère, Neveu, Alexandre-Joseph Paillet (1743-1814), Perrin, Pierre Remy, etc.) and amateurs such as the abbots Gruel and Le Blanc (1707-1781), the ducs de Caylus (vers 1733-1783) and de Chaulnes (1741-1792) and Randon de Boisset. The total sales for the Far East collections attained 23,775 livres 51 sols. The market value of the collection, though far from ridiculous, nevertheless did not reach the high prices of the estate sales of some of Boucher’s contemporaries, such as Randon, Louis-Jean Gaignat (1697-1768) and Jean de Jullienne. Among the many buyers mentioned in the margins of the catalogue, the duc de Chaulnes distinguished himself by purchasing at least twenty-five lots for a total of 3,131 livres 82 sols, the highest price being for a Chinese house for which he paid 1,199 livres 19 sols (lot 942) – a considerable sum for the Boucher sale. The six-paned Chinese lantern from the cabinet of the amateur Jean de Jullienne, won by Chaulnes for 730 livres 9 sols, stood out for its rarity and origin. Pierre Remy was the second buyer with seventy-one lots acquired for a total of 3,954 livres 81 sols. The merchants Doyen, Dufrêne, Julliot, Légere, Neveu, Paillet, Perrin followed further behind with about ten lots each. Though the collection was predominantly comprised of porcelains, lacquers and other objects highly appreciated by the amateurs, there waere also a number of rarer pieces that made it so singular. In the domain of porcelain, common pieces from China and Japan were mixed in with more precious types such as whites from Dehua 德華, celadons, celestial blues, crackled and flecked, forming an ensemble of 234 pieces of which one third is garnished with bronze. Ninety lacquers in fourty-three lots were placed auctioned off, most were boxes and trays of varying dimensions. The pieces most prized by the market were the ivories made for export, “pagodas in Indian clay” certainly made in Canton and objects made of “pierre de larre” (soapstone). Finally, Chinese bronzes, rarely imported in Europe, silver curiosities and musical instruments were the real singularity of this collection, proving once again that far from being merely a fad, this ensemble reflected Boucher’s genuine interest in the Orient.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne