ORLEANS Henri d' (EN)

Biographical article

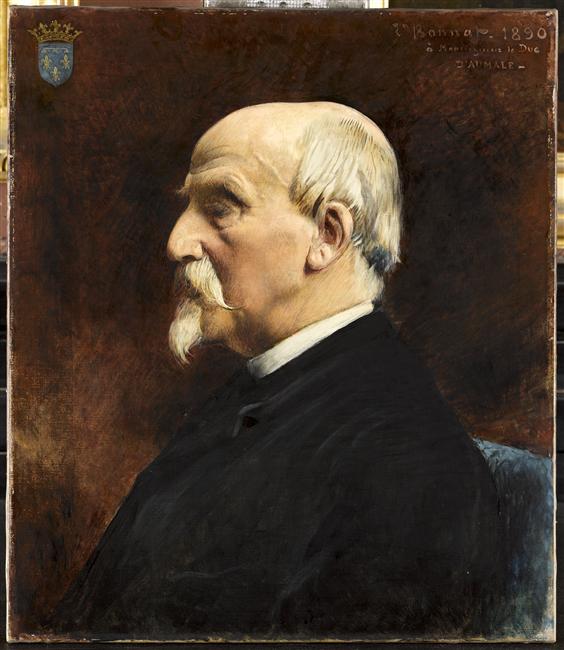

Henri d’Orléans, the Duc d’Aumale, was the fifth the son of Louis-Philippe (1773–1850), the last French king, and Queen Marie-Amélie (1782–1866). The godson and great nephew of the last Prince de Condé, Louis-Henri-Joseph, Duc de Bourbon (1756–1830), he inherited at the age of eight, in 1830, the immense fortune of the Condés, including the Palais-Bourbon (the present-day Assemblée Nationale) and the Château de Chantilly, which had been partly destroyed since the end of the Revolution. After completing classical literary studies at the Lycée Henri IV, at the age of eighteen, the Duc d’Aumale began a military career and went to Algeria where he joined his elder brother, the royal prince, Ferdinand, Duc d’Orléans (1810–1842). A brave soldier, he earned his epaulettes of Lieutenant-Colonel and was awarded the Légion d’Honneur at the passage of the Teniah de Mouzaïa in 1840 (national archives (AN), LH/667/59). Divisional General at the age of twenty-one, he distinguished himself by the capture of the Smala of Abd el-Kader (16 May 1843) and became Governor of Algeria at the age of twenty-five, replacing the old Marshal Bugeaud. With his close links to the army, he would always call himself a soldier. But the 1848 Revolution, which deposed his father, King Louis-Philippe, brought his career to an end and forced him into exile in England for twenty-three years, from 1848 to 1871. As governor of Algeria, at the head of an expeditionary force and seconded by his brother Joinville, who commanded part of the French fleet, he could have intervened militarily, but deeply attached to liberty he gave way to the will of the people (Cazelles, R., 1984, p. 149).

Having taken refuge with his family in Claremont, where the Orléans were welcomed by Queen Victoria, their cousin, the Duc d’Aumale was the only one left with a personal fortune that enabled him to acquire a fine residence, Orleans House, in Twickenham, south west of London. It was here that he assembled the collection that has turned Chantilly into the most important museum of old paintings after the Louvre and one of the greatest libraries in France for rare editions, manuscripts, and paintings.

He returned to France in 1871, after the fall of the Second Empire, a widower and without children (he lost his sons at the ages of twenty-one and eighteen); the Duc d’Aumale devoted himself to his collection and his Château de Chantilly. From 1875 to 1880, he restored the Renaissance wing built by Jean Bullant for the Constable Anne de Montmorency, or ‘Small Château’, and refurnished the historical apartments of the princes de Condé (eighteenth century), which had been emptied by the Revolution. Above all, with his architect Honoré Daumet, he reconstructed the main wing of the Château de Chantilly, or ‘Large Château’, which had been destroyed after the Revolution, so that he could exhibit his collections there (Musée Condé archives, series 4–PA and series CP). He displayed his pictures according to the standards of the era, on several levels, frame next to frame, using his own approach, in honour of the de Condé family and the royal family of Bourbon. Eager to avoid the dispersion of his collection after his death, he bequeathed it in its entirety in 1884 to the Institut de France (of which he was a member on three occasions: 1871, Académie Française; 1880, Académie des Beaux-Arts; then in 1889, the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques). His will comprised two important restrictions: the collections could not be loaned, nor could their presentation be modified—which makes Chantilly an irreplaceable example of a nineteenth-century museum (national archives (AN), MC/RS//1573). He continued to acquire major works until his death in 1897 and inspired many others: other major collectors, such as the Jacquemart-Andrés, bequeathed their collections, veritable private museums, to the Institut de France.

A member of Parliament for the Oise in February 1871, General Councillor of Clermont, and President of the General Council of the Oise département, the Duc d’Aumale fulfilled his political duties. In 1873, he was considered as a presidential candidate. But he was not a politician in the contemporary sense of the word (Woerth, E., 2006). The son of a king, a soldier acknowledged by his superiors, a historian, and an art lover and collector, the Duc d’Aumale was a person with many sides to his character, ‘a prince with ten faces’ (Cazelles, R., 1984), both a literary man recognised by the Académie Française, a politician who could have become President of the Republic, a highly important military leader and, of course and above all, an exceptional art collector.

The collection

Henri d’Orléans, Duc d’Aumale, is known for his collection of more than eight hundred paintings, more than four thousand drawings, and as many objets d’art, manuscripts, and precious books that he donated in 1886 to the Institut de France along with the Château de Chantilly to create the Musée Condé.

Books

In 1848, having been initiated by his tutor Alfred-Auguste Cuvillier-Fleury (1802–1887) to medieval manuscripts, incunabula, and rare editions, he claimed that he was already a ‘bibliomaniac’ (Musée Condé archives, 1–PA–103, piece 13, letter sent to Cuvillier–Fleury on 28 November 1848). He created one of the most extensive libraries in France after the Bibliothèque Nationale and in 1856 acquired in Italy one of the finest manuscripts in the world, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, executed by the Limbourg brothers circa 1410 for King Charles V’s brother.

Paintings

After 1848, the brilliant soldier, consigned to inactivity at the age of twenty-six, had to find an alternative occupation: already a bibliophile, he became a collector and, thanks to the fortune of the Condés, acquired French art treasures, in exile as he was abroad. In 1854, he purchased the collection of Italian painting (Carracci, Reni, and Salvator Rosa) and antiques belonging to his uncle and father-in-law, the Prince of Salerno (Musée Condé archives, Na 37/6). As the heir to the Orléans dynasty, he sought to recreate the collection of works of art of his ancestor, the Regent Philippe d’Orléans (1674–1723), dispersed during the Revolution by his grandfather, the guillotined Philippe Égalité (1747–1793), and form one of the finest collections of painting in France after the Musée du Louvre: three Raphaels, three Fra Angelicos, seven Nicolas Poussins, four Watteaus, four Greuzes, and five Ingres, not counting the contemporary works commissioned from his confrères from the Institut de France (Baudry, Olivier-Merson).

History

A descendant of the royal family of Bourbon, d’Aumale liked a painting to depict a story: he collected the portraits of historical figures. Having been awarded the second prize in history in the General Competition, he began work during his exile (1848–1871) on the publication of a monumental history of the princes of Condé (Musée Condé archives, 1–PA–2; 27–A–008). This was the origin of his collection of historical portraits, which comprised more than three hundred crayons by Jean and François Clouet, acquired in England and from the collection of Queen Catherine de’ Medici (Musée Condé archives, Na 39/1)—a collection unique in the world of sixteenth-century drawn portraits—, almost all of them the work of Carmontello, also bought in the British Isles, and almost five thousand prints.

Orientalism and late acquisitions

Another strongpoint in the collection is the Oriental works (Decamps, Marilhat, and Delacroix), which the Duc d’Aumale was very fond of, both as a soldier who had served in Algeria and as a follower of the Romantic movement, like his elder brother Orléans (Robert, H., 1993). Along with the collection of Frédéric Reiset (1815–1891), Director of the Museums Nationaux, d’Aumale acquired in 1879 forty masterpieces (Italian primitives, paintings by Poussin, and portraits by Ingres) (Musée Condé archives, Na 37), and then complemented his collection after the donation of 1886 with the forty illuminated manuscripts by Jean Fouquet taken from the book of hours by Étienne Chevallier, acquired in Germany from Brentano, paintings for a cassone by Botticelli and Filippino Lippi, and Corot’s Le Concert champêtre (Musée Condé archives, Na 37/4; AN, AP I 2150).

Asian art

It is less well known that d’Aumale also liked Asian art. Today, there are almost eighty objects in the visitor’s itinerary in the Musée Condé. The first curator of the Musée, Gustave Macon (1865–1930), counted ‘forty vases and dishes from China and Japan’, highlighting the fact that ‘the Chinese and Japanese vases have a great variety of styles, forms, and decorations’ (1928, p. 13).

The heritage of the princes of Condé

In 1830, the young Duc d’Aumale, who was eight at the time, inherited his first Asian objets d’art from his great uncle and godfather Louis-Henri-Joseph (Musée Condé archives, 4-PA-838* and 4-PA-839*), the Duc de Bourbon, the last Prince de Condé (1756–1830): the Japanese lacquer trunk representing roosters, hens, and chicks (OA 1798) and the hard porcelain vase-urn from Japan with Kakiemon decorations (circa 1690–1700) (OA 1031), as well as its soft porcelain Chantilly copy (OA 1032) came from Louis-Henri de Bourbon, Prince de Condé (1692–1740); a great collector of Asian art, he established in the eighteenth century the soft porcelain manufactory in Chantilly, inspired by the Kakiemon articles in his collection, and had the two Singeries de Chantilly painted, in which the Asian inspiration predominated (see the article by Mathieu Deldicque). On 19 September 1843, the Duc d’Aumale had the Japanese lacquer trunk brought to Chantilly and placed it in Monsieur le Prince’s Galerie des Actions, in the same place it had been between 1740 and 1793 (Carlier, 2010, p. 40, no.. 3), and added two small lacquer cabinets to it (OA 3451), which probably entered the Condé collection later. D’Aumale was intent on promoting the heritage of the Condés, and the Duc de Bourbon’s passion for Asian arts in the eighteenth century greatly influenced d’Aumale’s interest in Chinese porcelain wares.

The first acquisitions of Asian art during the July Monarchy (1845–1848)

In the Chantilly inventory dating from 1845 to 1848 (Musée Condé archives, 4–PA–838* and 4–PA–839*), of 139 porcelain articles belonging to the Duc d’Aumale, 36 were believed to have come from China; Japan is never mentioned, but was already present with the Arita vases (OA–1252–1253, OA–1561 and OA–1581) and the vase–urn that came from the Duc de Bourbon (OA–1031). With the Japanese lacquer trunk and the two cabinets, the Duc d’Aumale had brought thirty-nine Asian objets d’art to Chantilly before 1848. Some articles came from the Tuileries, such as the two Chinese quadrangular vases (OA 86); others were already in Chantilly, like the two large sang-de-bœuf eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Chinese porcelain vases (OA 1579–1580) mounted in gilded bronze in the nineteenth century, ‘discovered at Chantilly on 1 July 1845’ (OA 1579–1580). Between 1845 and 1848, the Duc acquired from the finest Parisian antique dealers several Chinese and Japanese porcelain wares, most often by the intermediary of the Romantic painter Eugène Lami (1800–1890). After his marriage with his cousin Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile (1822–1869) on 25 November 1844, the Duc d’Aumale did indeed entrust him with decorating their appartement de Chantilly, today the only surviving princely decorations from the July Monarchy. The first acquisitions were made in 1845: hence, the ‘two Chinese celadon porcelain vases, with gilt-bronze mounts, handles decorated with bunches of grapes’ (4–PA–839*, inv. 1845–1848, nos. 66–67), today in the Salon Violet (OA 2255), were acquired for 750 francs at Escudier’s on 30 September 1845. Eugène Lami acquired for the Duchess’s apartment ‘two green Chinese porcelain vases, with a crackled celadon glaze, and a gilded mount from the epoch of Louis XVI, amounting to 600 francs, Paris, on 7 August 1846, Félix Lajoye. For the Salon des Dames’ (OA 2255 (1–2); Musée Condé archives, Na 41/9, invoice), which are now located in the Grande Singerie (OA 329). In 1879, one of them was exhibited in the Salon de Guise, and the other in the Salon Rond (Salon Violet).

The Duc acquired for 45 francs from Escudier, a dealer in curiosities based in the Quai Voltaire, on 14 January 1846 (inv. de Chantilly in 1845, fo 28 no. 70), a hard porcelain hollow dish decorated with a landscape (famille rose ceramics (ceramics with pinkish hues), China, eighteenth century, Qianlong epoch, 1735–1795) (OA 2789), which is now in the Galerie d’Office; then from the dealer Henry on 24 May 1846 he purchased a ‘Persian blue Chinese vase with a square neck and cartels’ (OA 102) (Musée Condé archives, Na 41/9). Lami bought from Escudier on 13 July 1846 for 460 francs a celadon Chinese porcelain bottle with floral decorations, with handles, a base, and a stopper in intricately worked gilt bronze (OA 87; Musée Condé archives, Na 41/9); the work was naturally intended for the ‘Salon Chinois’, that is to say the Grande Singerie, whose decorations echoed the Asian objects. In May 1846, d’Aumale paid 1,400 francs at Escudier’s for a pair of black Chinese porcelain vases inlaid with mother-of-pearl, which came from the Duke of Sussex’s sale in London (OA 81).

The Duc d’Aumale acquired for 1,200 francs from Henry in September 1846 (inv. from Chantilly from 1845, folio 28, nos. 73–74) two large green vases with floral decorations on a square black ground (China, eighteenth century, Kangxi epoch) (OA 1559–1560), whose ‘green is of an extraordinary intensity’ and which Gustave Macon (1928, p. 13) described as a ‘superb specimen of this extremely rare and sought-after ceramic article from the Ming era’. In Twickenham, they were displayed in the Grand Salon.

In November 1846, three glazed vases from Japan (identified as Chinese) with ‘painted cartels with a white ground’ (OA 1252–1253), which were acquired for 550 francs at Gansberg’s; one, now lost, was ‘on the terrace’, and two ‘in the tableware room’. On 20 April 1847, Lami spent 1,500 francs at Gansberg’s—a dealer in curiosities and objets d’art based on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris—on two large Japanese Arita vases (believed to be Chinese at the time), produced circa 1690–1710 with lacquer decorations in relief (OA 1561 and OA 1581). Contemporary of the Duc de Bourbon, these two large vases imported from Asia were probably given their lacquer decorations in Europe. Eugène Lami placed them ‘on the tables in the Grande Galerie [des Actions]’. This was the most expensive purchase with regard to Far-Eastern porcelain wares aside from ‘four large Chinese porcelain urns, with a bronze ground and splendid flowers’, acquired from Lassalle, at 35, Rue Louis-le-Grand, for 2,700 francs (Musée Condé archives, Na 41/9), but subsequently sold to Beurdeley on 4 December 1852 (inv. 1845, nos. 122–125). Alongside these purchases, there was a donation by Edmond Halphen (1802–1847) in 1846: the eighteenth-century Chinese vase with a turquoise ground called ‘Peking blue’ (OA 75). As for the ‘two porcelain vases painted with flowers surmounted with a bouquet of 3 gilded bronze lumières’, now in the Queen’s room (OA 2163 (1–2), they were ‘brought by HRH Madame the Duchesse to England June 1852’. Amongst the lost articles were two ‘Chinese white celadon porcelain tabourets with floral decorations’ acquired on 5 August 1845 from Escudier on the Quai Voltaire (inv. 1845, nos.. 38–39; the Musée Condé archives, invoice, NA 41/9).

The exile in England (1848–1871)

After the fall of Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Aumale had his collections brought over to England, including his Asian porcelain wares. The Twickenham inventory mentions twenty-nine Asian articles out of the Duc’s 217 porcelain objects (Musée Condé archives, 4–PA–974*). The Duc de Nemours gave his brother d’Aumale ‘a large Chinese vase and gilded rocaille style bronzes’ (OA 103).

The return to France and the reconstruction of Chantilly

In 1879, the Chantilly inventory had a specific entry for the sixty-three ‘porcelain wares from China and Japan’, a country whose name appears for the first time. Twenty-five were stored in the Jeu de Paume, which was used as a store room, so it was probably these objects that had been brought back from Twickenham. Amongst them were Chinese tabourets (inv. nos. 181–182). Then there were ‘two Chinese porcelain cache-pots, with the arms of France’ (OA 66) from the Compagnie des Indes, ordered by Louis XV in 1739 (Castelluccio, S., 2011).

The private apartment housed Asian objects: a pair of grey-green celadon vases in the round salon, another in the Salon de Guise, but there were many nineteenth-century objects, such as the embroidered silk fireplace screen from the Duke’s room and the usual objects that graced his desk. D’Aumale returned the ‘grey Chinese porcelain tabouret’ to the Cabinet des Singes.

In the Musée Condé, at the entrance of the grand apartments in the Salon des Chasses, today called the antechamber, the Duc d’Aumale fitted two large curved showcases to house his Asian ceramic articles made from Chinese and Japanese porcelain, as well as jade pieces. This layout remains largely unchanged.

In the painting gallery, the two (nineteenth century) red leather circular sofas are surmounted with eighteenth-century Chinese vases. The Cabinet des Gemmes includes, aside from some Chinese objects, amongst which there is an eggshell porcelain plate (showcase XLII), large Arita vases, large black vases, and the pair of sang-de-bœuf vases.

After the second exile (1886–1889), the Japanese bronzes and the Exposition Universelle

The Duc d’Aumale acquired on 3 January 1891 from Pohl at 25, Rue d’Enghien, in Paris, the large Japanese bronze vase (OA 873) which was placed in the museum’s hall on 20 January; then on 28 February, again from Pohl, he bought two smaller Japanese bronze vases (OA 31–32), created in Kyoto by Yoshida in 1889 (the Duc d’Aumale’s diary in 1891, Musée Condé archives, 4–PA–30). The large bronze vase is said to have cost 10,000 francs and was believed to have been made in 1889 (Bouteiller, L., 1905, p. 35). According to the catalogue for the 1889 Exposition Universelle held in Paris (classes 11 and 25, pp. 7–8 and 15), the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in Tokyo displayed bronze flower pots and monumental bronze fountains, mostly made in Kyoto, of which certain models were unique. The Duc d’Aumale seemed to embrace the new taste for Far-East objects which were very popular at the end of the nineteenth century.

At the end of the Galerie des Cerfs, the reception dining room inaugurated in 1880, on the large glass doors and the accompanying cove, the Duc d’Aumale placed two Chinese screens; one of them in red silk embroidered with gold (OA 3477) bears an inscription dated 1835.

The salle Bourbon in Sylvie’s house

One of the most interesting ensembles of Asian art in Chantilly is held in the Maison de Sylvie, a building constructed in the park in the seventeenth century and transformed by the Duc d’Aumale into museum rooms in 1891. He devoted a room to Far-Eastern arts: the Salle Bourbon was named after Louis-Henri, the Duc de Bourbon and Prince de Condé (1692–1740). Amongst the most remarkable articles, aside from the Japanese lacquer trunk and the two lacquer cabinets that came from the Condés, the Salle Bourbon houses a major eighteenth-century piece of silk, a wall hanging with dragons, believed to have come from the Summer Palace in Peking (Macon, G., 1928, p. 42): this is an ‘imperial bed’ (OA 4455) decorated with dragons amongst clouds, in silk embroidery and metal threads on yellow silk satin. This impressive item, which measures 8.35 metres high by 2.1 metres long, was restored and studied in 2003 (Baptiste, Beugnot, Ducos, and Garnier, 2004). As a pendant, a large square wall hanging decorated with flowers and birds (OA 4464, restored in 2002) in silk embroidery on a ground of beige silk, measuring 3.52 metres high by 3.78 metres long, was believed in the nineteenth century to be an Asian billiard cloth (a provenance now discarded). Also worthy of mention are Japanese porcelain vases (stolen in 1975) and an ensemble of furniture comprising eight chairs and two armchairs (OA 3435–OA 3442, OA 3446 and OA 3447), probably produced in England in the Chinese style, a wooden pedestal table painted red and gold and in lacquer (OA 3388), an old table inlaid with mother-of-pearl from China or Vietnam (OA 3467), and a Western rattan armchair (OA 3445) covered in yellow and green fabric from the Chinese robe of an official from the second half of the nineteenth century, with a dragon in the middle of the back rest.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne

Sommaire

- The collection

- Books

- Paintings

- History

- Orientalism and late acquisitions

- Asian art

- The heritage of the princes of Condé

- The first acquisitions of Asian art during the July Monarchy (1845–1848)

- The exile in England (1848–1871)

- The return to France and the reconstruction of Chantilly

- After the second exile (1886–1889), the Japanese bronzes and the Exposition Universelle

- The salle Bourbon in Sylvie’s house

- The collection

- Books

- Paintings

- History

- Orientalism and late acquisitions

- Asian art

- The heritage of the princes of Condé

- The first acquisitions of Asian art during the July Monarchy (1845–1848)

- The exile in England (1848–1871)

- The return to France and the reconstruction of Chantilly

- After the second exile (1886–1889), the Japanese bronzes and the Exposition Universelle

- The salle Bourbon in Sylvie’s house