MONTIJO de, Eugénie (EN)

Biographical Article

María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina Palafox y Portocarrero was born on May 5, 1826 in Granada, as the second daughter of Don Cipriano Palafox y Portocarrero, Count of Teba, and Doña Maria Manuela, daughter of William Kirkpatrick, United States Consul in Malaga. Her youth was spent between Spain, Paris, and London. In 1849, the young Comtesse de Teba moved to Paris with her mother and met Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, President of the Republic who would become Emperor Napoleon III in 1852. Her marriage to Emperor Napoleon III, eighteen years her senior, was celebrated at the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris on January 30, 1853. The couple had one son, Napoléon Eugène Louis, Prince Imperial (1856-1879).

Empress Eugénie was patroness of the China expedition in 1859-1860. In June 1861, alongside the Emperor in the ballroom of the Château de Fontainebleau, she received the ambassadors of Siam, who brought with them gifts that the Empress then incorporated into her "Chinese museum". In 1863, she set up the "Empress's Chinese Museum" at the Château de Fontainebleau, with objects from the capture of the Yuanmingyuan, the Summer Palace of the Emperors of China (Droguet, V., 2011, p. 53-57; Samoyault-Verlet, C., 1994, pp. 16-26). Also in Fontainebleau, Eugénie installed a study in 1868-1869 with Oriental decor, in which Japanese furniture and objects were placed. A few years earlier, in 1866, Eugénie had built for herself and her Spanish family a new hôtel particulier on rue de l'Élysée in Paris, in which she had placed a large part of her collection of paintings. One of the lounges in this residence featured a Chinese-style ceiling (regarding this residence, see McQueen, Alison 2011 and 2021-3, pp. 33-51). When the Second Empire fell, the Empress moved with Napoleon III and their son to England. She died in 1920 in Madrid, at age ninety-four (C. Pincemaile, 2000).

Musée d'Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

The Collection

From 1861, Empress Eugénie (1826-1920) found herself in possession of an important collection of objects from the Far East, with various origins, which she installed in her Chinese museum or in her office at the Château de Fontainebleau.

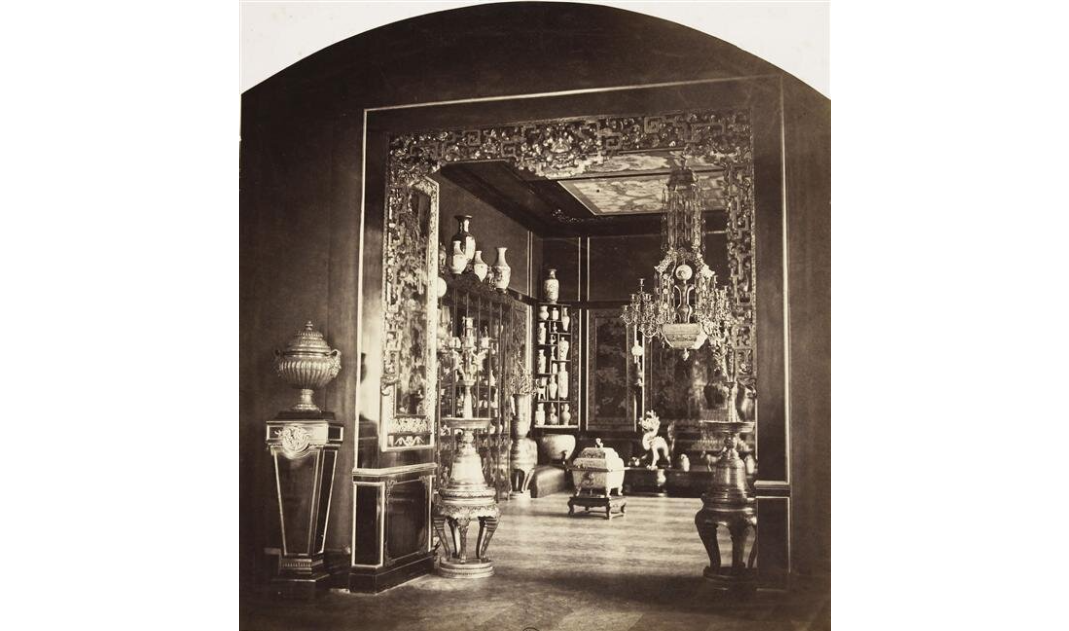

The first set, by far the most numerous and most important, was made up of the shipments to the imperial couple of objects taken by the Anglo-French expeditionary force from the Yuanmingyuan or Summer Palace, which since the 18th century had been the main residence of the emperors of China. The capture and looting of the Yuanmingyuan by the English and French contingents took place in October 1860 and the objects intended for the imperial couple were selected under the responsibility of General Cousin-Montauban, commander of the French army in China. The objects left China in November 1860 and were shipped to France (G. Thomas, 2008). They were divided into four headings: the first entitled Army, under which were recorded 96 "Chinese objects offered to H. M. The Emperor by the army"; two other headings entitled 1st and 2nd sendings, under which appeared respectively 53 and 23 "Chinese objects sent to the Empress"; and finally, a 3rd shipment corresponding to 201 "objects in old Chinese porcelain, sent to H. M. The Empress", i.e. a total of approximately 380 objects (ACF, Archives du Château de Fontainebleau 1C160/1 and 2). Delivered to Paris at the beginning of 1861, these Chinese objects were presented from the end of February on the ground floor of the Pavillon de Marsan inside the Tuileries Palace as part of a temporary exhibition under the auspices of the Emperor and Empress. Photographs taken by Eugène Disdéri on this occasion and engravings published in the press (Auguste Allongé et Émile Roch, “Exposition des curiosités chinoises offertes à l’empereur pas l’armée expéditionnaire”, Le Monde illustré, 5e année, no 203, 2 mars, 1861; Jules Gaildrau, “Trophée d’objets chinois”, L’Illustration, Journal universel, vol. 37, no 941, 9 mars 1861, p. 149; Anonymous, “French Spoils from China Recently Exhibited at the Palace of the Tuileries”, in Illustrated London News, vol. 38, 13 avril, 1861, p. 334) show how the works were presented in the exhibition. After the end of this exhibition, the weapons and armour - in particular the armour of the Qianlong Emperor - were sent to the musée de l’Artillerie (the present-day musée de l’Armée), while most of the art objects were put back into their shipping crates. However, a few of these objects were placed by Empress Eugénie in two of the private rooms in her apartments at the Tuileries, her study and her painting studio. Two paintings by the painter Giuseppe Castiglione, kept at the Fundacion Casa de Alba in Madrid and dated 1861, show the Chinese works that Eugénie kept near her. In particular, one can note two ewers and their enamelled gold basin (F 1467 C), a large enamelled copper stupa (F 1359 C), three enamelled bronze chimeras (F 1362 C and F 1404 C), and two gilt bronze bells dated 1744 (F 1363 C). It was not until the spring of 1863 that all the Chinese objects, including those that had been placed in the Empress's apartments at the Tuileries, were sent to Fontainebleau to be displayed in the rooms of the Chinese Museum of the Empress, on the ground floor of the Gros Pavillon (Archives du château de Fontainebleau, no. 18599).

As part of the Chinese museum, the objects from the Yuanmingyuan were immediately joined by the gifts of the ambassadors of Siam, about 70 in number, which had been kept in Fontainebleau since June 1861 and which represent the second most important set of works from the Far East that came into the hands of the imperial couple, after those from China. These Siamese objects had arrived with the embassy sent by King Rama IV Mongkut (1804-1868), which had been received in audience by Napoleon III and Eugénie, in Fontainebleau, on June 27, 1861 (Droguet, V., 2011, p . 53-57).

Under the direction of the Empress and in her presence, the Chinese objects and the Siamese objects were arranged in display cases, on furniture, or in shelves made for the Chinese museum and the salon preceding it. Due to their dimensions, the painting representing the Emerald Buddha (F 1768 C) as well as the palanquins (F 1764 C and F 1774 C), the parasols (F 1748 C, F 1749 C, F 1750 C and F 1771 C), and the weapons (F 1755 C, F 1756 C, F 1769 C, F 1770 C, F 1776 C and F 1777 C) that accompanied them were installed in the antechamber of the suite of salons and the Chinese Museum. Three of the four large Kesi, discovered in a “cave” within the Yuanmingyuan compound by Lieutenant Des Garets (Garnier des Garets L., 2013, p. 193-194) were installed on the ceiling of the Chinese Museum. In order to complete this presentation, Eugenie took several Asian objects out of the Crown storage room: two 18th-century Chinese screens in lacquer of black and gold backgrounds respectively, which were dismantled and split so that the panels could adorn the walls of the Chinese Museum, as well as porcelain confiscated during the Revolution from the collections of the Princes of Condé at Chantilly: two pairs of vases with a white background and figures in relief (F 1384 C and F 1388 C) and a pair of mounted chimeras on a gilt bronze base (F 1736 C) (Samoyault-Verlet, C., 1994, p. 16-26).

Shortly after the installation of these objects and the inauguration of the Chinese Museum of the Empress on June 14, 1863, the manager of the chateau drew up a specific inventory of Oriental objects, which was established with the collaboration of the dealer Nicolas Joseph Malinet (1805-1886) (Archives du château de Fontainebleau, Registre-inventaire du Musée chinois, pièce no 19985). This inventory included the headings under which the Chinese objects had arrived. However, the manager added a final section, entitled Miscellaneous (Divers), which included both Chinese objects that were sure to come from the Summer Palace, such as the basin and the two enamelled gold ewers (F 1467 C), the two vases in embossed gold (F 1432 C), the two large dragons in gilt bronze (F 1360 C), and the three large Kesi tapestries (F 1305 C), but also objects from other sources and other origins. Among these, we find in particular the objects brought as presents by the Embassy of Annam, which came to France at the beginning of the year 1864, as well as objects from Japan, some of which were acquired or recovered by the imperial couple after the death of the Duc de Morny, the Emperor's half-brother, in 1865. These Japanese objects that arrived in Fontainebleau in 1865 (a series of ten kakemonos, lacquer boxes, and vases in particular) also correspond to diplomatic gifts brought by embassies of the shôgun (Droguet V., 2021, p. 19-21).

Until the end of the Second Empire, the salons and the Chinese Museum of the Empress at the Château de Fontainebleau were frequently visited by the imperial couple and their guests during the stays of the court. The letters of Octave Feuillet in particular, the chateau librarian at the end of the 1860s, recount the atmosphere of the evenings at the Chinese Museum, which came to take on the role of reception room for the sovereign (Mme O. Feuillet, 1894). The Asian collections were installed and displayed for purely decorative purposes, without concern for scientific classification, and the term ‘museum’ as applied to the room containing most of the Oriental curiosities should therefore not be taken in the sense given currently to this word, but rather in the sense of a cabinet of curiosities, such as there were many examples throughout Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Contrary to the great apartments of the chateau, the salons and the Chinese Museum of the Empress were not accessible to visitors, and only rare figures of high rank or coming particularly highly recommended, and having obtained a special pass, could access these rooms and the Oriental collections brought together in Fontainebleau by Eugénie. Thus, no photo of these salons and of the museum was published under the Second Empire, nor was a catalog of the collection established. The objects therefore remained unknown to connoisseurs, apart from the presentation at the Tuileries at the beginning of 1861 of Chinese objects from the Yuanmingyuan.

In 1868, work began on the installation of a study for the Empress on the ground floor of the Louis XV wing, not far from the salons and the Chinese Museum and directly linked to the study of the Emperor, which was fitted out in 1864. This new study of the Empress was decorated with the elements that were already used in the Chinese Museum: the walls were covered with Chinese lacquer panels from a screen acquired in 1805 from the merchant Rocheux (Samoyault, 2004, p. 321-328, no 262) that had been part of the furnishings of the Château de Fontainebleau since that date, while the ceiling of the room received the last of the four Kesi found in the Yuanmingyuan. The antechamber of this cabinet was even hung with Chinese wallpaper, delivered by Maigret frères, and arranged in faux bamboo mouldings (Archives du château de Fontainebleau (Bâtiments), 1868/2, Attachments de Maigret frères, fabricant de papier peint, 3 boulevard des Capucines in Paris, December 22 and 29, 1868). The furnishing of the study included Oriental furniture and in particular two cabinets in aventurine lacquer (F 1796 C 1-2), a screen painted on a gold background (F 1815 C), and furniture with shelves also in lacquer (in particular F 1799 C) that corresponded to Japanese diplomatic gifts offered by the ambassadors of the shôgun in the 1860s (E. Bauer, 2021, p. 65-74). Additionally, there was a Chinese armchair (F 1779 C) of unknown provenance, Japanese bronze vases inlaid with silver (F 1320 C), mounted as lamps, that had been directly purchased by the furniture store from the painter François-Auguste Ortmans in 1868(Archives du Château de Fontainebleau (Régie), exhibit no. 21149, Letter from Thomas Moore Williamson, dated June 29, 1868), a small table bearing the stamp of the cabinetmaker Grohé, with a Japanese lacquer top (F 1801 C), nesting tables in red lacquer (F 1802 C) delivered by the merchant Chanton in 1869 as well as three other "Chinese style" tables, with gilded bamboo legs and a lacquer, acquired from the merchant Stecker. A niche in the room had been hung with a silk fabric embroidered with glass beads, with Chinese motifs, acquired from the widow Perrier (F 1791 C) (Droguet, V., 2013, in particular p. 114-125 ).

The installation of this study, which was intended to become a very private room for the sovereign, was not completely finished in 1869 and the Empress Eugénie probably never took full possession of it. Nevertheless, the oriental taste that presided over its layout, both for the decor and for the furnishings, confirms the extent to which the sovereign, at the end of the Second Empire, appreciated the fact of being surrounded by works from the Far East in the most intimate spaces of her existence. One might naturally wonder, beyond Eugenie's clear inclination for these exotic objects and pieces of furniture, about her investment in their choice and selection. The Chinese, Siamese, Japanese, and Annam objects and furniture which had been brought together in Fontainebleau in the salons and the Chinese Museum, then later inside the study, also called the lacquer salon, had not been collected or chosen by the Empress. With very few exceptions, Napoleon III and Eugenie had received these works as gifts, and the Empress had seemed rather satisfied with installing and arranging them in a frame entirely designed to showcase them. From this point of view, Eugénie's position in relation to these objects is of course very different from that of dedicated collectors of Oriental art from that time, such as Edmond and Jules de Goncourt.

However, the personal investment of the Empress in the implementation of these decorative sets and in the installation of the works within rooms which had become - or were to become - places frequented daily by the Imperial couple and their guests during stays in Fontainebleau testifies to a real projection of Eugenie in these Oriental collections and an authentic attachment vis-à-vis these objects from the Far East, to which she was willing to give an important role in her living environment.

After the fall of the Second Empire in 1870, and the exile of the imperial family in England, the objects remained preserved in Fontainebleau. The Republic and the ex-sovereign disputed the possession of the Oriental collections from Fontainebleau, but Eugénie was never to recover the objects from the Chinese Museum (E. Viollet-le-Duc, 1874). However, a certain number of objects and pieces of furniture installed in the study were considered until the very end of the 19th century as the Empress's own property, but these were never returned.

The salons and the Chinese Museum of Fontainebleau were refurbished under the Third Republic, a process that removed their appearance as reception salons. They were opened to the public as a museum from 1876. Eugénie's former study was included in the apartment of the President of the Republic.

Restorations on the salons and the Chinese Museum, as well as that of Eugenie's study, began in 1984, with the aim of reconstructing as faithfully as possible the arrangements of the Second Empire. The Chinese Museum, restored with the objects put back in place according to the inventories and the rare photographs of the time, opened to the public in 1991. The Empress' study or lacquer room, restored during the same campaign, had to wait until 2013 and the end of the restoration of Napoleon III's study to be visible to visitors to the chateau. Despite the gap left by a theft at the Chinese Museum in 2015, these two places still to this day conserve almost all of the Oriental collections that the Empress Eugénie had installed there.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne