Monseigneur began collecting as of 1681 (Castelluccio, 2002, p. 136). the Grand Dauphin was not as interested in pictures, busts and marble sculptures as he was in hardstone vases, bronze statuettes, and porcelains. Louis XIV furnished his apartments in Versailles and Meudon with paintings and sculptures from the royal collections, which remained the property of the crown. Monseigneur therefore had no need to acquire pictures, but he did purchase from his own funds objets d’art, which were considered his own property. The Grand Dauphin’s collections are well known thanks to an inventory first drawn up in 1689, and updated until at least 1702. This inventory was sold in London, at Sotheby’s, on 2 December 1998 and is now held in a private collection. Entitled Agates, cristaux, porcelaines, bronzes et autres curiosités qui sont dans le Cabinet de Monseigneur le Dauphin à Versailles, inventoriez in MDCLXXXIX, it consists of the following seven sections: Agates, Cristaux, Porcelaines, Porcelaines données par les Siamois, Orfèvrerie donnée par les Siamois, Bronzes et Pendules et Bureaux. This inventory includes a very precise description of each object, with its dimensions, price, and name of the person who gave it to Monseigneur, along with its inventory number and its location in Versailles or Meudon. Each object bore a label featuring the inventory number, its price, or the name of the donator, a label still visible on certain vases held in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

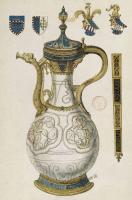

The Grand Dauphin inherited a great passion from his father for hardstone vases and rock crystal. He had collected 452 hardstone vases, an ensemble that exceeded that of the royal collections, that comprised 377 objects in 1713. However, his 246 rock crystal objects were no match for the 446 items in the royal collections inventoried that year (Castelluccio, 2002, p. 45). Monseigneur’s hardstone vases were distinguished by the luxuriousness of their mounts adorned with polychrome enamel work, and the most sumptuous of them were decorated with cameos and precious stones. Monseigneur’s other great passion was collecting Chinese porcelains. He had collected 380 of them, which exceeded the number of rock crystal objects. Sixty-four of these porcelains originated from the diplomatic present offered in 1686 by the ambassadors of the King of Siam (present-day Thailand). There were mostly blue and white porcelain wares, consisting of 336 items, as these were the most common objects in the European market in the second half of the seventeenth century (Castelluccio, 2013, pp. 66–69). An indication of their importance in the eyes of the Grand Dauphin, thirty-eight of them had a gilt silver mount and some of them were even adorned with gold decorations. The porcelain objects with polychrome decorations were few in number, while the Japanese objects were not of any particular interest to the Grand Dauphin, who was not interested in sculptures and only owned two seated porcelain figures. The few monochrome pieces included four in pale beige and nine grey and green celadons. The most surprising and ancient piece was a celadon bottle with floral decorations and cordons in relief, adorned with an exceptional mount attributed to Charles III de Duras, King of Naples. Louis XIV probably gave him nine large bronzes in December 1681 (Castelluccio, 2002, p. 152). Six represented the Travaux d’Hercule (‘Labours of Hercules’), another two Alexandre et Bucéphale (‘Alexander and Bucephalus’) from the Piazza del Quirinale in Rome, and the last, the Enlèvement des Sabines (‘The rape of the Sabines’). Up until 1689, Monseigneur acquired thirty-one bronzes. Louis XIV gave him another two works in 1689—the Lion contre le cheval (‘Lion attacking a horse’) and the Lion contre le taureau (‘Lion attacking a bull’)—, which he had just been bequeathed by the painter Charles Errard (1606–1689), as these were subjects the Grand Dauphin did not own. After 1689, another ten bronze works were added to the collection; however, the absence of any mention of price and name of the donator makes it impossible to specify the mode of acquisition. The quality of the casting, chasing, and patina of the nine bronzes offered by Louis XIV in 1681 meant that the collection was of a very high standard. Even if he had no real interest in the objects, the Grand Dauphin sought the finest pieces for his collection, which reflected less his own taste than that of his era for subjects and artists considered prestigious. Hence, sixteen bronzes were reduced scale copies of antique pieces and nine of the works by Jean de Bologne (1529–1608) and his followers. At least four pieces were produced in French workshops, including perhaps Femme à sa toilette (‘A woman bathing her feet’), attributed to Barthélemy Prieur (1536–1611). More rare was the group of Hercules, Deianeira, and Nessus , attributed to Adrien de Vries (1545–1626): a present from Louis XIV, it had come from the collections of Emperor Rudolph II (1552–1612). Upon his death, the Grand Dauphin owned fifty-two bronzes and two small ivory bacchanales listed in the same section, despite the different materials. Like his father, Monseigneur believed that around fifty objects was enough for his rank. He preferred gemstones and porcelain, the only kinds of object offered by his family, friends, and courtesans. The section entitled ‘Orfèvrerie donnée par les Siamois’ included the forty-five pieces of precious metal offered as a diplomatic gift by the ambassadors of Siam, who were received on 1 September 1686 in the Galérie des Glaces in Versailles. The nineteen gold objects were complemented by twenty-six silver items, from both China and Japan. They comprised a ewer, basins, dishes, and trunks. In 1689, the year when the silver furniture was melted down to fund the War of the Ligue of Augsburg, the Grand Dauphin sent the Monnaie twenty-one of these objects. The remaining twenty-four probably disappeared during the second phase of melting in 1709. The last section of the 1689 inventory comprised pieces of furniture, such as thirteen clocks and seventeen items of cabinet-made furniture. The clock maker Nicolas Gribelin (1637–1719) made five of them, Balthazar Martinot (1636–1714) made two, Henri Martinot (1646–1725) at least one, and the fourth only bore the name of Martinot, without a first name; the last of these was attributed to l’Allemand. Henri Martinot made the most luxurious of the clocks, with its gilt silver case adorned with diamonds and rubies and its diamond hands. Gribelin made the most authentic one, in ‘blue and white, like porcelain’ framed by two terms of Mercury and Apollo, and highlighted with decorations, with the entire piece made from gilt copper. The furniture section comprised fifteen tall socles (‘scabellum’), used to display bronze works, and girandoles, eight desks, four gueridons, a wardrobe, a cabinet, and a trunk. The cabinet had been ‘made by Boulle’, while the Grand Dauphin had purchased the wardrobe and a desk from the marchand-mercier Daustel (1646–1718). Of these thirty items of furniture, twenty-one were decorated with Boulle marquetery, a form of ornamentation highly appreciated by the prince.

As the heir to the throne, the Grand Dauphin displayed the finest objects from his collections in Versailles, the official residence of the kings of France. As of 1683, he lived in a ground-floor apartment in the south-west corner of the central building. In its finished state, after 1693, Monseigneur had placed some of the finest porcelain wares in his gilded Cabinet, which was created between 1684 and 1687 on the site of the Dauphin’s bedroom. The panelling painted with arabesques on a gold ground framed pictures from the royal collections and mirrors. The porcelain pieces were placed on gilt wood consoles. Gribelin’s blue and white clock had probably been placed in this room. Then there was the Cabinet des Glaces, located in the Dauphin’s second antechamber. Created between 1684 and 1685, it was the most impressive room in the apartment’s suite of rooms. Its marquetry floor, created by the cabinetmaker Pierre Gole (circa 1620–1684), echoed the coffered ceiling adorned with mirrors and marquetry on an ebony ground. André-Charles Boulle created the marquetery panelling, which alternated with mirrors. Again, in the interests of prestige, Monseigneur placed more than 600 objects there, with 344 hardstone vases, which were amongst the finest and most spectacular, 199 crystal pieces, twenty-three bronzes, and silver and goldsmithery from Siam. The objects were arranged on carved gilt wood consoles, attached to the glass panels. Monseigneur probably placed either Martinot’s vermeil clock, or a smaller one decorated with gold and diamonds in the Cabinet. In contrast with contemporary practises, Monseigneur did not combine pictures and objets d’art. Very soon, the Cabinet des Glaces became one of the most famous areas in Versailles due to its rich decorations and the objects it contained.

In the Château de Meudon, the Gallery and various rooms in the Prince’s apartment were adorned with bronze and porcelain objects. The latter created a Cabinet des Bijoux on the mezzanine floor; it was fitted with boiseries à la capucine, meaning simply varnished natural wood panelling, with gilt ornamentation. He placed ninety-nine porcelain objects on the cornice, according to the fashion of the times, and objects in wardrobes. Monseigneur installed 118 hardstone vases, fifty-two crystal pieces, twenty-seven porcelain pieces, and silver and goldsmithery from Siam, but no bronze objects. In contrast with Versailles, there was no desire for ostentation in the Cabinet des Bijoux in Meudon, which was on the mezzanine floor—it could only be visited upon the prince’s invitation—, with its simple decorations and objects contained in cupboards.

Upon the death of the Grand Dauphin, his collections, considered as his own goods, were treated like those of an ordinary individual. The objects seen as the most prestigious—the hardstone and rock crystal vases, the bronze statuettes, and some items of furniture—were shared amongst his three sons. Upon the death of the Duc de Bourgogne in 1712, and of the Duc de Berry two years later, their shares were added to the royal collections. As was customary, several items and all of the porcelain collection were sold at auction in Marly, from 9 to 15 July 1715, to settle the Prince’s debts (Castelluccio, May 2000; Castelluccio, 2002, pp. 168–176). Parisian dealers, collectors, and courtesans acquired objects at this sale. The quality of the porcelains was such that the mention of a provenance from the Dauphiné region in the sale catalogues, such as those of the Duc de Tallard in 1756 and the Duc d’Aumont in 1782, was intended to act as a guarantee of excellence (Rémy-Glomy, 1756, pp. 257–258 and pp. 263–264, no. 1066; Julliot-Paillet, 1782, p. 82). The Grand Dauphin’s collections represented male taste in the second half of the seventeenth century and the large number of collected objects and their characteristics highlighted his rank. The nobility and the rarity of the materials, as well as the richness of the mounts were worthy of the king’s son as successor to the throne, as was the splendour of the decorations of his Cabinets in Versailles.

Items from the Grand Dauphin’s collections are held in various institutions: the Musée du Louvre has hardstone vases and bronzes; the Museo del Prado in Madrid holds the hardstone vases that Philippe V inherited; several items of furniture adorn the royal residences; the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin has a celadon bottle, but it is missing its medieval mount; and the Wallace Collection in London holds two of d’Algarde’s Chenets (Andirons or fire dogs).

Article by Stéphane Castelluccio (translated by Jonathan & David Michaelson)