The Auction in Lucerne, June 1939

As of 1935, the Nazi cultural policy became radically stricter. Artworks were no longer just objects of slander⎯modernist works of art in the German museums were sorted and destroyed. Art exhibitions were closed and works of art were confiscated; it was the beginning of a policy of ‘cleansing’ in order to get rid of ‘degenerate’ art.

The campaign conducted by Nazi Germany against ‘degenerate’ art

An initial ‘cleansing’ operation of this type had already been conducted in 1930 at the Weimar museum, when Wilhelm Frick, a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), was appointed to a State Ministry in Thuringia as Minister of the Interior and Minister of Education and ordered all modernist paintings to be removed from the museum: works by Otto Dix, Ernst Barlach, Lionel Feininger, Erich Heckel, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Emil Nolde, Edouard Munch, and many others.

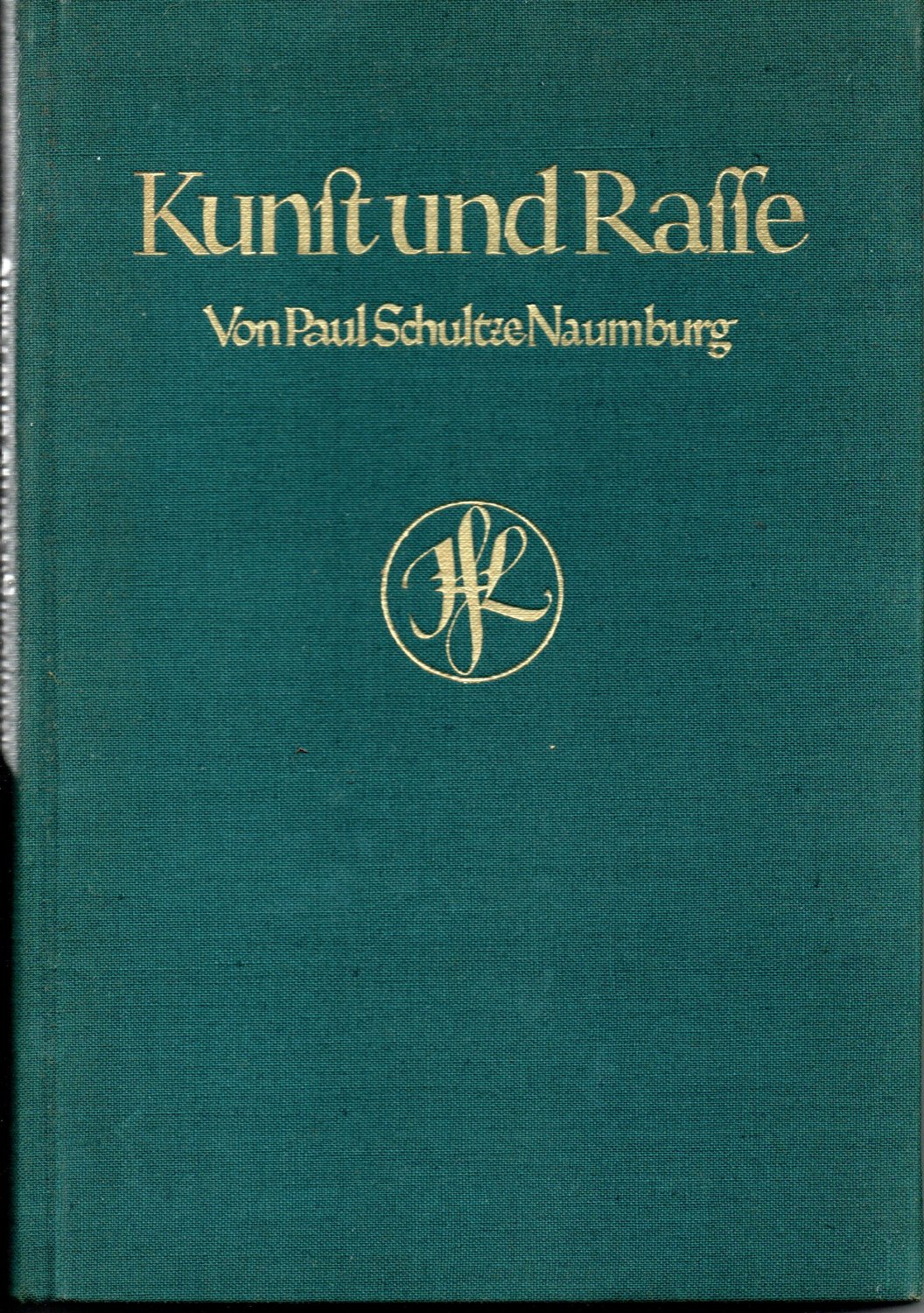

The Nazi ideologues believed that the realistic genre of painting of the nineteenth century was the culmination of a long tradition of ‘Aryan’ art. The avant-garde was on the other hand deemed to be a ‘mental illness’. Paul Schultze-Naumburg, an architect and racial theorist, denigrated modernist art in his book Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race) in 1928, in which he described it as ‘degenerate’ and compared examples of modernist art to photos of mentally ill and disabled people1.

Hitler used these attacks to fuel mistrust of modernism amongst German citizens and impose his political objectives against the Jews, Communists, and ‘non-Aryans’.2

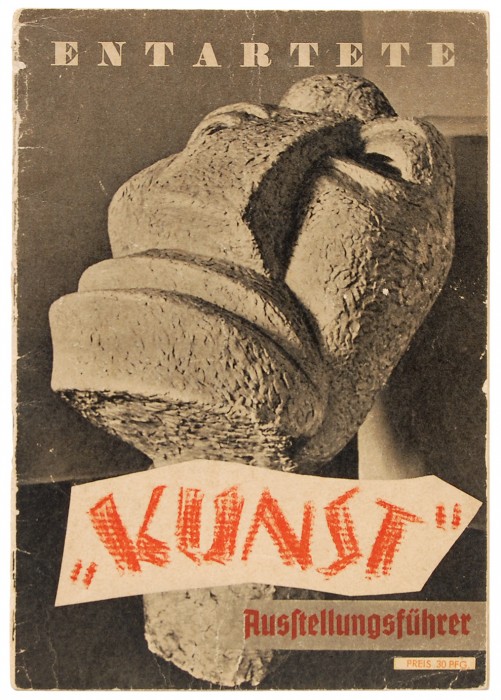

Under the Nazis, who had been in power since 30 January 1933, the ‘exhibitions of shame’ method was henceforth employed on a large scale, culminating in 1937 in the itinerant exhibition ‘Entartete Kunst’ (‘Degenerate Art’), which began in Munich and was subsequently held in various German and Austrian towns and cities up to 1941. ‘The year 1937 definitively marked the end of the German avant-garde'3 wrote the researcher Gloria Sultano.

The propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, instructed the President of the Chamber of Fine Arts of the Reich, Adolf Ziegler, to set up a committee which, during the first half of July in 1937, selected around 1,100 works of art from thirty German museums. As of 19 July, around 600 of these works were presented at the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition in Munich.4

‘The works were shown to the public as symptoms of the degeneracy of the Weimar Republic, with the aim of discrediting it and celebrating the victory of the National Socialists as a “new revolutionary start”’.5

As of 6 August 1937, the committee set up by Ziegler visited around a hundred museums and confiscated more than 20,000 works by over 1,400 artists, including the works exhibited in Munich. Most of the museums were visited by the committee before mid November. The confiscated works were transported to Berlin and stored in the Victoria-Speicher (Victoria Warehouse) on the Köpenicker Straße.6

It was only one year after these events that a law was promulgated in order to create the ‘legal’ basis to exploit these works, whose presence on the walls of German museums was deemed illegitimate by the Nazis.

On 31 May 1938, the ‘Law on the Confiscation of Products of Degenerate Art’ stated that ‘The products of degenerate art, which have been seized in museums and collections accessible to the public before the passing of this law and have been identified by authorities appointed by the Führer and the Reich Chancellor, can be seized without compensation on behalf of the Reich, provided that they were guaranteed to be owned by nationals or domestic legal entities at the time of confiscation'.7 The stage was thus set for the sale of the confiscated works. The official term used by the Nazi regime was ‘Verwertungsaktion’, a technical term, a euphemism, which could be translated by ‘recovery and valorisation’; but, this term conceals the regime’s real objective: the destruction of this unwanted art or the sale of the works for currency abroad.

The acquisitions and exchange operations were conducted exclusively through four authorised art dealers, as of the end of 1938 and until the end of the ‘campaign of destruction’ in the summer of 1941: Karl Buchholz and Ferdinand Möller in Berlin, Hildebrand Gurlitt in Hamburg, and Bernhard A. Böhmer in Güstrow. They were required to sell the works abroad, but they also sold some of them to art dealers and collectors in Germany, or kept some for themselves. In any case, they had to find sources of foreign currency.

The auction at the Fischer Gallery in Lucerne

This is the background against which the auction at the Fischer Gallery must be understood. On 30 June 1939, the Theodor Fischer Gallery in Lucerne organised an auction entitled ‘Paintings and Sculptures by Modern Masters from German Museums’, during which 125 major works were put up for sale.

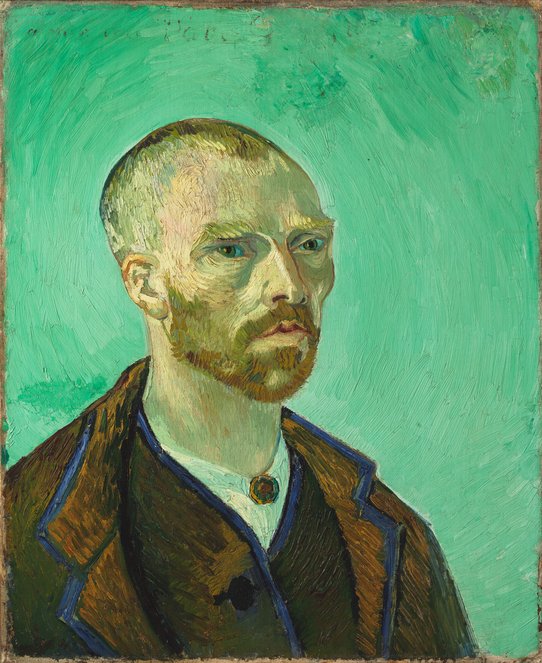

The aim was to obtain the highest possible prices for some of the key works, such as the Self-Portrait by Vincent van Gogh, De Tahiti (former title, now entitled: The Witch Doctor of Hiva Oa) by Paul Gauguin, as well as four paintings by Picasso. The prices of German Expressionist art had however fallen to its lowest level. ‘Circa 1940, the paintings by [Christian] Rohlfs and [Otto] Mueller were worth around 30 dollars; works by [Ernst-Ludwig] Kirchner, [Karl] Hofer, and [Max] Beckmann were worth a little bit more’.1

It was Theodor Fischer who contacted the German Ministry of Propaganda in the autumn of 1938 to put forward the idea of an auction. The proceeds from the sale were to be paid into a foreign currency account in London, available for the ‘German Reich’ (‘the German Empire’). Fischer was to receive a commission of 15%, but only 6% for the six most valuable paintings.2At the end of April 1939, 108 paintings and 17 sculptures were sent to Zurich for an initial viewing; they were exhibited for six days before being transported to Lucerne.

On Friday 30 June 1939, the auction was held at the Grand National Hotel in Lucerne. Amongst the 350 people invited to attend the auction were collectors from Switzerland, the United States, Belgium, England, France, and even Germany, as well as representatives of the museums of Antwerp, Basel, Bern, Brussels, and Liège. There were many well-known figures amongst the buyers: Alfred Frankfurter, editor of ‘Arts News’ and advisor to the American collector Maurice Wertheim, Pierre Matisse, the art dealer and son of the painter, Joseph von Sternberg, a Hollywood filmmaker and collector, Joseph Pulitzer Jr., editor and publisher and grandson of the famous journalist with his wife Louise Vauclain, Curt Valentin, a German Jewish art dealer who fled Nazi Germany in order to open a branch of the Buchholz Gallery in New York.

The main attraction was a self-portrait by Van Gogh, acquired at the auction for 175,000 Swiss francs by Alfred Frankfurter for Maurice Wertheim. It is now held at the Harvard Art Museum, to which Wertheim bequeathed his collection.3 The Brussels collector Roger Janssen acquired the painting Acrobat and Young Harlequin by Picasso for 80,000 Swiss francs. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in Liège did not only acquire The Witch Doctor of Hiva Oa by Gauguin for the sum of 50,000 Swiss francs; the museum also invested in eight other masterpieces at an additional cost of 56,000 Swiss francs.4 The city of Liège wished to make use of the opportunity to compile a collection of contemporary art and turn the city into a modern cultural centre.

The director of the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Georg Schmidt, received the sales catalogue in mid April 1939 and immediately contacted Hildebrand Gurlitt and Karl Buchholz. He personally went to Berlin in order to inspect, in the presence of two German art dealers, all the works confiscated by the Nazis. He soon realised that many masterpieces had remained in Berlin. Hence, he was able to reserve thirteen major German works of modernist art which did not feature in the Lucerne catalogue for the museum in Basel. This is how the canvas Ecce Homo by Lovis Corinth, The Bride of the Wind by Oskar Kokoschka, and Animal Destinies by Franz Marc entered the collection in the Kunstmuseum.5

Calls in the media to boycott the auction

The preparation for this auction did not proceed without causing a stir in the international art scene. In April 1939, the art critic Paul Westheim (1886-1963), who was living in exile in Paris, warned against any participation in the auction in Lucerne:

With regard to the auction it should be noted that: every buyer must be aware that with the foreign currency he pays for these artworks, he lends aid to the Third Reich, strengthens its armaments fund; anyone who takes part in this auction by submitting bids must realise that he is not supporting the artists, but is instead granting despisers of art an additional bonus for their philistine actions.1

His calls to boycott the auction featured in various journals published by exiles: in the Neue Weltbühne, in the journal Freie Kunst und Literatur (‘Free Art and Literature’), which he had himself directed, in the newsletter of the Freie Künstlerbund, an association of artists in exile, which, in 1938, had organised in Paris an exhibition to counter the slanderous ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition in Munich, and in the Pariser Tageblatt, a daily journal for which he regularly wrote art critiques as of 1933. These articles were the logical continuation of his anti-Nazi art critiques, which he published in Paris.

The former editor of Das Kunstblatt, one of the most influential art critics in the Weimar Republic, had with his journal (founded in Berlin in 1917) created a forum for the European avant-garde, and had, above all, promoted Expressionism. Like many German intellectuals, Westheim went into exile in France in 1933 to fight against the Nazis.2He was not only threatened because he was Jewish, but also because he was a spokesperson for modern art. His name and his art journal were vilified along with paintings by Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and George Grosz in the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition. In June 1935, Paul Westheim¾simultaneously with Bertolt Brecht, Erika Mann, and Walter Mehring¾was stripped of his German citizenship by the Nazis.3

It is difficult to assess the extent to which Westheim’s public criticism of the auction resonated in the international press. He only wrote about the auction in German. However, it may be supposed that his stance contributed to spreading the idea that the auction would benefit the rearmament of Nazi Germany. The editor-in-chief of the American journal Art News, Alfred Frankfurter, became aware of the situation and sent a telegraph to Theodor Fischer on 1 June 1939. ‘In order to dispel the rumours’, he asked about the aim of the auction, ‘in the hope that it will encourage bids from the United States’.4

Fischer replied the following day:

The proceeds on 30 June are not going to the German government; all the payments are going to the Fischer Gallery - stop - The funds are going to German museums for new acquisitions - stop - The rumours are coming from Paris, spread by a prominent art dealer who wants to inspire confidence with political arguments, although he has spent large sums of money in Germany - stop - I authorise you to publish this statement. Compliments, the Fischer Gallery.5

It is not possible to accurately determine who was designated as a ‘Parisian art dealer’. In the specialised literature, Georges Wildenstein (1892-1963) and the gallery owner Paul Rosenberg (1881-1959) were described as critics of the auction.6 The main effect of the calls to boycott the auction and the media coverage was to give much publicity to the event.

The Burlington Magazine saw things in a surprisingly calm way, without emotion and with much lucidity. The auction was announced in the magazine in May 1939, thus:

(...) All the works mentioned come from German Museums. They were ‘purged’ on account of their alleged ‘degenerate’ and ‘Bolshevist’ character. Revolutions have often in the past led to the dispersal of art collections and thus aroused interest in particular schools of art in new quarters. There is little doubt that in the present case new admirers will be found for these rejected works in an atmosphere free from political prejudice.7

The relationship between Georg Schmidt and Paul Westheim

In the specialised literature on the auction organised by the Fischer Gallery, the director of the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Georg Schmidt, and Paul Westheim1 are portrayed as having conflicting views about the auction: Schmidt, who acquired ‘degenerate’ art for the Basel museum not only at the auction, but also in Berlin, versus Westheim, who, as an exiled German Jew, publicly warned against ‘the destruction of German museums’ through the auction.

New previously unpublished sources do however show that the two men were closer in their views than was thought. Fragments of correspondence, which was originally more voluminous, between the exiled art critic and the future director of the museum in Basel, are held in the Special Archives of Russia in Moscow.2

Schmidt and Westheim began to correspond in 1937, when the latter was preparing the exhibition to counter the slanderous ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition in Munich. He was seeking advice from the Swiss journalist who was yet to become director of the museum in Basel. Their correspondence reveals two key elements: firstly, Georg Schmidt openly expressed his support for Paul Westheim, whom he saw as a model because he was a veritable champion of modern art. He wrote to him in a very open and personal way: ‘Apart from the exhibition, it gave me a great deal of pleasure to receive your letter, because, for once, I received a direct sign of life from you. Your Kunstblatt was indeed for many years the modern art journal for the younger generation’.3

Secondly, Schmidt’s policy is evident in the correspondence: defending modern art and, in particular, Expressionist art, but not doing so too openly or in a demonstrative way on a political level. Schmidt thus warned Westheim against becoming too directly involved in any opposition to Nazism and introducing the public to modernism, for which he was not yet ready.

(...) Here, in Switzerland, for example, one can also cultivate much more anti-Nazi sentiment, by simply writing in a newspaper: the world famous painting by the greatest German painter in the twentieth century [Franz Marc], The Tower of Blue Horses, was condemned by the Nazis! But if you show modernist art, it will provoke a pro-Nazi reaction. The values of modern art are not yet established for that (...).4

Other fragments of letters dating from before 1939 attest to the fact that Schmidt and Westheim subsequently had a very confidential exchange of letters. It soon became evident that they had similar political views and stances on art. With his Kunstblatt, Westheim had always fought to promote contemporary modern art, particularly a socio-critical art that did not shy away from depicting social upheavals and psychological conflicts (like those in the works of Otto Dix, George Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka, and Edvard Munch). Schmidt was in line with the tradition of the art journal; he was a committed socialist and, as of 1933, he helped refugees who had fled from Nazi Germany. They did not wait until 1939 to set about saving modern art. It may even be conjectured that their opposing public views on the Fischer case concealed a well thought-out strategy.

When he returned from his trip to Berlin, Georg Schmidt wrote to Westheim about the major works that he had reserved for his museum. To obtain the necessary loan from the city of Basel, the young museum director Schmidt had to fight an uphill battle all the way.

The day before the Fischer Gallery auction in Lucerne, on 29 June 1939, the parliament of the Canton of Basel-Stadt approved a loan of 50,000 Swiss francs for the acquisitions. Around half of the money was used by Schmidt and his colleagues to acquire works at the auction in Lucerne, as the remainder was kept in Berlin for the reserved paintings. In his letter to Westheim, Schmidt described the heated discussions in the committees, where he had many opponents.

(...) a great struggle with a committee that was largely opposed to my choice, and which, during all these years, has rejected any acquisition of works by German Expressionists. But I succeeded, mostly because the Social Democratic Minister of Education of Basel supported me passionately.5

Westheim’s unequivocal reply to Schmidt reflects the approach of the exiled art critic, who also wanted ‘degenerate’ art to remain in the museums, away from the grip of the Nazis, and recognised internationally. He did not only congratulate Schmidt for his acquisitions, but also praised him by calling him the ‘saviour of contemporary German art’:

Wonderful! I must congratulate you, you and the delegation from Basel. The paintings Ecce homo [Corinth], Animal Destinies [Marc], The Bride of the Wind [Kokoschka], The Parents of the Artist by Dix … all the masterpieces (...). And I am particularly pleased that my so-called call to boycott the auction helped you in your endeavours. So we are still good at something. I tentatively said that everyone must be aware that they are helping strengthen the Third Reich’s weapons capability by buying works at the auction in Lucerne, because of the situation as it was originally. I knew that Goebbels was really hoping that the objects would be returned unsold (...). The failure of the auction (...) would prove that the ‘Führer’ was right, as always. There’s nothing to be done with these ‘degenerate’ artists (...). All things considered, there’s a good chance that Goebbels was right. And the consequences would have been catastrophic for the exiled artists (...) If the auction had failed, we would nonetheless have been able to say that it was not due to a lack of artistic value, but rather the public aversion to Goebbels’ desire to obtain foreign currency (...). The fact that so many people have taken the opportunity to acquire these masterpieces at a low price and that the ideology behind the exhibition in Munich has been firmly rejected, is (...) a source of great encouragement for the slandered artists (...) The fact that you took the initiative with such zeal is wonderful and the fact that you have saved these major works from the claws of the Nazi barbarians¾really saved them, because after the destruction of artworks during the pogroms, the works were at risk in the long term¾is also very commendable from the point of view of German art and the German people (...) I am convinced that your name will always be mentioned (...) when the way in which these masterpieces of art were safeguarded for the cultural world is recounted (...).6

It appears that Westheim, a victim of the Nazi regime, regarded any sale abroad of a work of art labelled as ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis as a way of ‘rescuing’ the work. He also underlined its importance for living artists, whose works would benefit from international recognition. His calls for a boycott were part of a strategy that aimed to draw the public’s attention to the situation, prompted by the fear that works of modern art, which had been stigmatised and confiscated by the Nazis, would not find buyers abroad. Through his criticism in the press, he drew public attention to the Fischer auction. Behind the scenes, he had already discussed the situation with Schmidt at the beginning of 1937. Their strategies were complementary and they had a shared objective: saving modern art from the destructive acts of the Nazis and placing modern artworks on responsible museums, which were capable of ensuring that they gained international recognition.

Two months after the Fischer auction, the Second World War broke out. In September 1939, Paul Westheim was interned as a ‘enemy alien’ by the French government. For more than two years, he went through various phases of internment, interrupted by periods of liberation, before leaving Europe for Mexico at the end of 1941. Schmidt and Westheim continued to correspond in a very collegial way. Their correspondence continued throughout the war.

The art dealer and auctioneer Theoder Fischer achieved some success in the initial auction of ‘degenerate’ works. The total amount of the proceeds (price under the hammer) was 570,940 Swiss francs. Out of the 125 works put up for sale, 86 were sold. Theodor Fischer received a total of 57,000 Swiss francs in fees and commissions. After deducting payments to the German Reich, his net profit was 24,323 Swiss francs.7 During the Second World War, he was involved in the resale of works of art confiscated from Jewish families in the countries occupied by Nazi Germany, in particular in direct collaboration with actors in the French art market.

Basisdaten

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique