ADELINE Jules (EN)

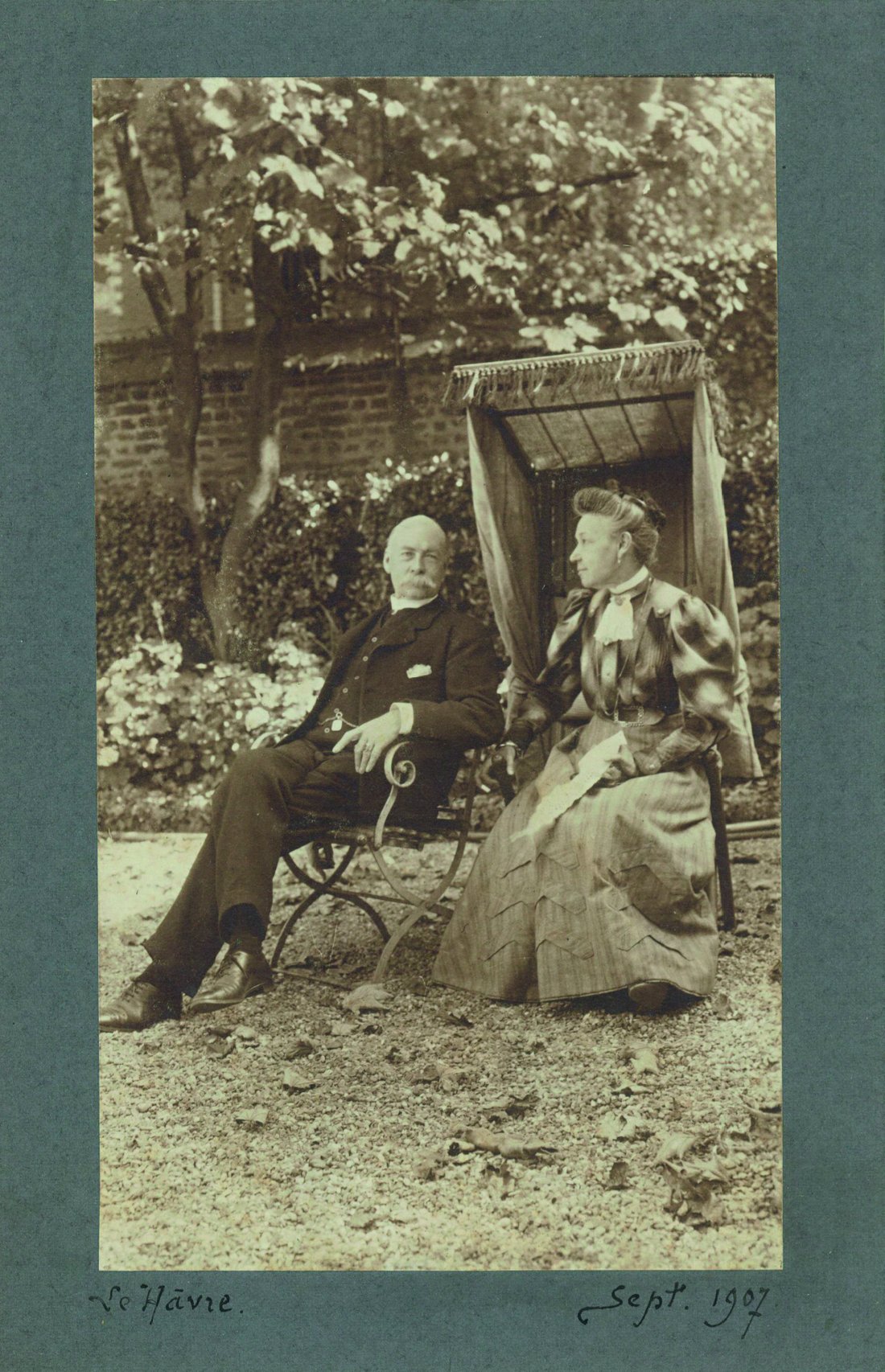

Jules and Valentine Adeline, Curious Collectors

Until recently, Jules Adeline (1845-1909), an architect and painter of watercolours, was a figure that remained in the shadows - the shadow of some of his dark illustrations, which appeared in large numbers in Rouen books. He was the quintessential illustrator of the medieval old town of Rouen.

In 1973, the discovery of some watercolours from the uchronic 1900 anthology Rouen tel qu’il aurait pu être (Rouen As It Might Have Been) (Adeline J., 1910, p. 45), then in 1996, the public sale of his library accompanied by numerous unpublished works, has reoriented the gaze of historians and enlightened aficionados. Foresighted and concerned about the future of his collections and production, at his death in 1909, Adeline bequeathed a large part of his work to the library of Rouen, his graphic arts collections to the museum of painting and his remarkable Asian collection to the museum of Rouen. Living with, for, and in their theatrical collections specially staged in their home at 36, rue Eau-de-Robec in Rouen, the artist and his wife Valentine Adeline (1855-1907) illustrate the rich and little-known approach of a couple of curious and meticulous collectors.

Born in Rouen and a student at the Lycée impérial, the young Jules Adeline apprenticed with an architect from Rouenbetween 1863 and 1870. Weary of working as a project manager, he did not continue in this path following the conflicts of 1870, with the exception of realising some commemorative monuments throughout his career.

Adeline was marked by a childhood, in which print was omnipresent, in particular the large woodcuts of the Magasin Pittoresque that he copied or coloured daily. In the corridors and living rooms of the family home, young Jules encountered the collections of his father, the artist and annuitant Louis André Adeline (1807-1871). In 1865, at age 20, Jules Adeline, fascinated by all these images and suffering from "acute catalogue-ography” (Adeline J., 1910, p. 36), felt compelled to inventory these collections and compiled two handwritten files listing his father’s works: first, a catalogue of the library of nearly 300 items, then a second for paintings and drawings, of 41 works, completed with 1,035 engravings. Composed of drawings by Grandville (1803-1847), originals from the Napoleonic campaigns of Hippolyte Bellangé (1800-1866) and Charlet (1792-1845), watercolours by Camille Roqueplan and Alfred Johannot, hundreds of engravings including by Henri Breviaire, as well as a large collection of 350 illustrated prospectuses, the collections of Jules Adeline's father would remain in the house until his death, after which they would be included in the scenography in the rooms of the new home acquired by the couple as of 1874.

Adeline, liberated from his profession as an architect, quickly published, from 1876, collections of etchings such as Rouen disparu (1876), Rouen qui s’en va (1876), Le Musée des Antiquités et de Céramiques (1882), and Les Ponts de Rouen autrefois et aujourd’hui (1879), to which he fully committed his technical and artistic know-how, for luxurious portfolios printed in small numbers. In addition to these bibliophilic publications, Adeline soon began a second production of popular books, such as the Lexique des Termes d'Art (1884), published in three languages including more than 20,000 copies for France, and Les Arts de Reproduction Vulgarisés (1895).

Thanks to his continual research, the architect-engraver developed a multitude of centres of interest: archaeology, history of architecture, history of costumes, photography, theatre, museography, scenography, posters, Japonisme, cats... Gradually transformed in compulsive collections, these various passions would be published in Adeline’s illustrations or texts, taking the form of covers, letterheads, initials, or articles intended for the circle of bibliophiles of the city of Rouen, as well as for many national newspapers and magazines.

Becoming friends with Chamfleury (1821-1889) as of 1872 due to their common love of cats, it was undoubtedly through the Manufacture de Sèvres, where Champfleury was an administrator, that Adeline's Parisian relations sharpened. For Adeline, the annual visits to the Salon or to the Universal Exhibitions (1878-1898) represented unexpected opportunities to discover the Parisian artistic world, as well as to meet the promoters of Japonisme. His rich correspondence and notes allow us to clearly identify today his knowledge and relationships with great 19th centurycritics or artists such as Louis Gonse (1846-1921), Philippe Burty (1830-1890), Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), Arsène Houssaye (1814-1896), Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914), Jules Chéret (1836-1932), Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), Émile Gallé (1846- 1904), and Parisian publishers such as Albert Quantin (1850-1933), Léon Conquet (1848-1997), and Emile Testard.

Champfleury's interest in Japan is very evident in his book Les Chats, but also through his taste for ceramics and earthenware, which he studied as administrator of the Manufacture de Sèvres. The joint work undertaken for the second edition of the Violon de faience (1885) was an opportunity for Champfleury to send Adeline a book of prints in 1883, which he recommended he study for the production of the fifteenth etching entitled Le Rêve de Dalègre. It was actually album no. 3 of Hokusai's Manga from which Adeline copied the head of the ghost of a woman threatening a man with her claws, to integrate into the etching requested by Champfleury.Adeline's first sketches, engravings, drawings, and annotations attest to his infatuation with oriental artistic work, a taste that grew from 1873. In the various collections accessible today, there are some fleeting testimonies of this infatuation, such as a Japanese business card project and above all a very elaborate watercolour from 1874 representing a European woman in a Japanese store, in the style of Henry Somm. Adeline's relations with the latter probably opened the doors to publishing the brand new review Paris à l'eau-forte from 1873. Adeline was invited by this weekly founded by Richard Lesclide (1825-1892) and the painter Frédéric Régamey (1845-1925) to illustrate the texts of the various writers with etchings. In the January 4, 1874 issue of L’Art et la curiosité, Richard Lesclide’s article is illustrated by what is perhaps Adeline’s first vignette dealing with the still nascent theme of Chinoiseries. This small etching, clumsily engraved, with calligraphy trying to approach ideograms, is far from the quality of the Japanese prints copied among others by Frédéric Régamey for the article Le Japon - premier récit.

Upon the marriage of Jules Adeline in 1874, the partnership of acquests contracted between the two spouses noted works of art, among other things, for the groom. However, it is impossible to specify more solidly the exact content of these terms or to clearly map out the artist’s discovery of Japan. It is nonetheless certain that the collection bequeathed in 1909 to the city of Rouen was in the process of taking shape from the start of Adeline's marriage to Valentine Houssaye, The couple seems to have gradually immersed themselves in Japonisme, integrating this current into the simple events of their daily lives. Even the couple's animals blended into this image of the floating world with, at first, “Houdan hens, whose proud attitudes still made one think of Japanese woods”, and then peacocks (Adeline J., 1910, p. 14 ).

For the Adelines, cats, Mi-ki-ka dolls, and their home’s interior swiftly became inseparable subjects, emblematic of the couple. Their calling cards consistently refer to these three themes. Throughout his career, starting in 1874, Adeline even incorporated Japanese writing into his cards and various drawings. These small calligraphies might evoke a dialogue, a name, even the character of a cat. The correctness of the drawing of the ideograms is not as precise as might be desired and does not always stand up to the expert work of translation. But the concern to keep the tone and to "do Japanese" was inseparable from the work of Adeline, who did not hesitate to seek assistance from Japanese people in his research.

But what characterises the Adeline couple above all was the desire to stage their collections. Indeed, the house at 36, rue Eau-de-Robec was a small provincial museum in its own right. Some Parisians, like Émile Gallé, came to visit this little environment created by the couple. Maurice Guillemot, director of the Revue monégasque (1893), travelled to enjoy a visit to Adeline and, amazed, published a laudatory article on this little paradise in Rouen at the foot of the waters of the Robec.

Over thirty years, Adeline's purchases seem significant in quantity, but do not present any true quality. The search for the "rare piece" was not the determining objective of this passion, and Adeline mentions, in several places in his writings, the purchase of trinkets or small prints for a few cents. Adeline thus frequented a good number of Japanese art sellers. The sometimes lasting relationships with these sellers no longer need to be demonstrated, and the privileged relationships, during purchases, at Mitsui, rue Saint-Georges, or at the Bazar Parisien in Paris were not the only entry points for acquisitions. On the back of some of the prints purchased in Paris by Adeline is the stamp of the shop À l'Empire Chinois, 53 rue Vivienne, Thés et Chinoiseries, listed since 1863 in Paris. He therefore buys in all these shops, which sold a bit of everything related to the Orient, before refining his research and seeing the birth, particularly as of 1878, of galleries like that of Siegfried Bing, Fantaisie japonaise, at 19 rue Chaussat in Paris.

Each work exhibited in the house was installed in such a way so as to promote a sort of kinetic process of research, cherished by Jules Adeline, through its movement within a room. He used large Japanese pieces to structure the space, especially the pagodas at living room corners. In his Logis et l’Œuvre (1910), he specifies the desire, shared with his wife, to find the right place for each object.

The collection was not conceived solely as a simple accumulation of the greatest number of pieces, but as an element to be integrated into the couple’s daily life and the living space. The different views of the Adelines’ interiors provide a glimpse of what the enumeration of various collections implies: a piling up of a "very 19th century" cabinet of curiosities, nonetheless rebalanced by the didactic inclinations of this engraver and architect.

Although Adeline’s training oriented him towards the graphic arts, his collection of Japanese art embraced all artistic fields. Over the course of travels and visits, the couple, or Adeline alone, accumulated numerous prints (Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro, Kunyoshi, etc.), ceramics (dishes, vases, sculptures), statues, pagodas, masks, dolls, swords. The couple's collection also included trinkets, small animals, kakemonos, posters, fans, toys, various objects such as small paper theatres, as well as some furniture used to present Japanese items (lamps, shelves, chests of drawers, etc.).

If Adeline did indeed own pieces in all artistic fields, the theme of dolls was particularly well represented. There was a large series of pieces in the bamboo shelves of the living room on the first floor of the house on rue Eau-de-Robec. Adeline was one of the first specialists in Japanese dolls. Here we find warriors, samurai, Noh theatre actors, dancers, and deities. The Noh masks hung here and there in the house do not, however, constitute a large set and most were hung in the second-floor workshop where Adeline took refuge to work.

In 1885, the collection already included the centrepieces of the Adelinian museum: the mannequin in armour, the ceramics, the pagodas, even the famous Mi-ki-ka doll, bought before 1883. This figure of Mi-ki-k, whose engraving, refused at the Salon of 1887, would be exhibited at the Galerie Duran-Ruel in 1890 at the second exhibition of painters-engravers, subsequently accompanied the Adeline couple on their calling cards, letterheads, postcards, self-portraits, etc. In the inventory of the Adeline bequest in 1909, 106 pieces are referenced, many of questionable quality.

Adeline's Japanese paintings were neither old, nor masterpieces of Japanese art. Adeline, like other collectors, got his items in Parisian boutiques without necessarily looking for the unique or old piece. Adeline was even mistaken about the dating of the Mi-ki-ka doll, which he placed in the 18th century, a hundred years too early. But for the couple, who sometimes made discoveries and make purchases together, then for Adeline alone, after his wife’s death, these pieces have a sentimental, even melancholy value. They are memorial markers of travels and a shared life, memories of encounters or presents from friends more or less close, such as those of Siegfried Bing. The Adeline's Nyngyo were manipulated and staged, their clothing or accessories could be changed, thus proving the couple's ignorance of both Japanese traditions and the role of some of their dolls in Japanese society.

Only a few pieces from the collection, now deposited at the Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Rouen, were remarkable: a Samurai Mi-ki-ka doll, now missing from the inventories and not located; a Noh mask for an old man's role, dated from the late 17th or early 18th century; mid-19th century O-yoroi samurai armour; but also larger pieces that go well beyond a simple collector's purchase. We thus find the multiple pagodas or the large Japanese bronze of which Adeline was particularly fond, drawing and describing it on numerous occasions.

Adeline's Japanese collection, as we have seen, was an integral part of his home and collections. In his work, both engraved and designed for many Rouen and Parisian publishers, Adeline constantly introduced elements from his collection into his compositions. For example, in writing the book Le Chat d’après les Japonais (1895), taken from speeches at the Academy of Rouen, Adeline demonstrates both a great knowledge of the representation of cats in Japanese artistic and artisanal production, as well as of artists and their techniques. For this, he reproduces in lithography details of prints by the great masters such as Hokusai or Hiroshige. These models were directly studied from the books, magazines, and originals that he kept in large numbers in his library.

Adeline was committed, as a great art lover, to an in-depth observation of his prints, and the choice of acquisitions for his collection was relevant to his other centres of interest. His collection of dolls was one of the only ones of this scale in France and, as such, was noticed by more than one aficionado. Adeline used his dolls in the compositions of many drawings taken from photographs that he staged himself.

To perfect the dissemination of this unusual Japanese gathering, Adeline undertook a new work in 1890: Poupées et Magots. It is initially composed of 25 etchings and an accompanying text. For this publication, the collector took the time to dramatise his collection in the antechamber of the grand salon and to photograph his stagings. In this book, he associated in his photographic compositions his dolls with other ceramics or Japanese trinkets. From these 24 photographs, only four etchings would be engraved and the projected album would never be completed, nor published, as Adeline noted in 1909 in his catalogue raisonné under the heading “planned work”:

[The album] would have reproduced the Japanese dolls (in costume), the Coloured Statuettes, the Stoneware, etc., from my collection, pieces collected over more than 30 years, from a number of Japanese dealers in Paris, whose stores have long since ceased to exist, and which bear no resemblance to the horrible and vulgar dolls and statuettes of today. (Adeline J., 1910, p. 14)

From 1874 to 1900, Adeline was isolated as a scholar of Japan in Rouen. He found himself almost alone, with the exception of Jules Hédoux (1833-1905), a lawyer and ambassador of this passion. It is possible, all the same, through his work, to discover some Rouen customers open to Japonisme. Jules Adeline was a meticulous artist and anxious to learn about everything and in particular graphic techniques. To do this, he visited a number of sometimes specialised exhibitions, such as the exhibition of Japanese engravings held in 1890 at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His discoveries were regularly reported in the communications and articles he publishes.

For Jules Adeline, Japanese art was the pinnacle of an art that he sought to appropriate in Europe. Colours, precision, accuracy, intelligence of the line, and attention to the narration of the image were for him qualities only achieved by Japanese prints. He even concluded his opuscule on Le Chat chez les Japonais with an unqualified verdict: “[…] we will always be inferior to the artists of the charming country of the Far East.”

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne