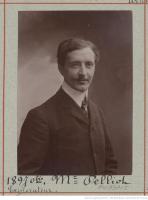

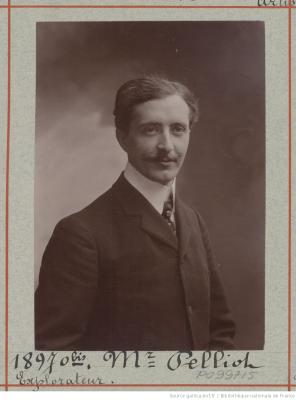

PELLIOT Paul (EN)

Paul Pelliot, a career as a collector in the service of France

Youth and training

Paul Eugène Pelliot was born on 28 May 1878 in Paris as the fourth child of Marie Renault (1848-1923) and Charles Théodore Pelliot (1847-1930) who was an industrial chemist. He grew up with six siblings in Saint-Mandé (Val-de-Marne) and completed part of his education at the Collège Stanislas in Paris. As he considered pursuing a career in diplomacy, he studied in the capital at the Faculté des lettres, the École des Sciences politiques and the Collège de France. He began to develop his linguistic abilities at the École pratique des Hautes Études (Sanskrit and classical Chinese as an auditor) and at the École nationale des langues orientales vivantes (Chinese). He obtained a degree in the literature and a diploma in political science in 1897 and then received a diploma in Chinese in 1898. With his talent for learning at an early age, the young Pelliot caught the attention of many of his professors, most of who are well known, such as the professors of Oriental languages Arnold Vissière (1858-1930) and Maurice Courant (1865-1935); the sinologist Édouard Chavannes (1865-1918); the indianists India Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935) and Émile Sénart (1847-1928). They all recognised the talent of their student and encouraged him to orient himself toward research. In 1899, an opportunity to apply the linguistic and cultural knowledge that he had acquired so quickly presented itself when he was appointed boarder at the Mission archéologique d'Indochine, which became the École française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO) the following year. At only 21 years of age, Paul Pelliot became involved in the first major mission of his career. During this mission, he developed a method of scholarly action that allowed him to prove his value, to test his abilities and to collect books and pieces of art.

Early days at the EFEO

As a member of the EFEO from 1899 to 1911, Paul Pelliot only worked directly for the school for about five years (Goudineau Y., 2013, p. 21). Despite this, he took advantage of his stays in Indochina and significantly contributed to the study of Chinese sources for the geographical history of Southeast Asia (Bourdonneau E. et Manguin P.-Y., 2013, p. 29) with reference articles published in the Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, such as "Mémoires sur les coutumes du Cambodge, par Tchéou Ta Kouan" (1902), "Le Fou-nan" (1903), "Deux itinéraires de Chine en Inde à la fin du VIIIe siècle" (1904). In 1904, he also published a "Première étude sur les sources annamites de l'histoire d'Annam". These productions demonstrated his investment in the service of the École as well as the benefits of a sinological approach to local historical sources. Building on his previous successes in China, Pelliot thus perfectly responded to the expectations that had been enumerated during his recruitment. Between 1900 and 1902, he carried out three missions, each lasting over six months, during which he collected printed documents on behalf of the EFEO. Thanks to Pelliot, around 10000 booklets came to enrich the young institution’s library that became thus one of the largest collections in Europe (Goudineau Y., 2013, p. 22-23). The result of this collection was decisive for French sinology, which, until then, had suffered from a lack of documentary resources. This success is tied to the researcher’s ability to take action and to the judicious choices that he made with the guidance and advice of his professors, as evidenced by a letter from Sylvain Lévi dated 5 May 1900 (archives Pelliot, musée Guimet, Pel C1a). Pelliot also brought back 150 Chinese paintings from his first mission to Beijing (today conserved at the musée Guimet) as well as a collection of Tibetan Buddhist statues (today conserved at the EFEO in Paris). In addition to this prodigious collection, Paul Pelliot's achievements include being the youngest volunteer to participate in the defence of the legations during the Boxer Rebellion (Darcy E., 1901, p. 830) and being made a knight of the Legion of Honour for his bravery.

The mission to Central Asia

On 2 August 1905, Pelliot was entrusted with the direction of an important scientific mission to Central Asia, which had multiple objectives, both scientific and geopolitical due to the Great Game that took place in this highly strategic and still little explored region at the beginning of the 20th century. To the great dismay of Pelliot who was under the impression that the best places had already been taken (Trombert É., 2013, p. 49), France belatedly joined the forces that were already present. The major discoveries that were achieved beginning at the end of the 1880s revealed the significant potential for research to be conducted in this territory where Bhuddism flourished throughout the first millenium AD. Particular attention was paid to the unknowned ancient texts that circulated there and that could appear during archaeological excavations. Despite their delay, the French mission was given substantial resources, proof of the project's ambition, thanks to the support of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres and, to a lesser extent, the Société de géographie commerciale de Paris and individuals who were coordinated by the Comité de l'Asie française. Louis Vaillant and Charles Nouette accompanied Paul Pelliot throughout this 27-month-long journey (departure from Paris on 15 June 1906; arrival in Beijing on 4 October 1908). The first was a medical offcier in the colonial army and took charge of the work of cartography, astronomy and natural history. The second in a professional photographer. Pelliot recorded the course of the expedition in his travel diaries kept today at the Musée Guimet (Ghesquière J. et Macouin F., 2008, 488 p.).

The mission’s success can be attributed to the collection that was made in Dunhuang in 1908. Without this collection, the expedition would not have been considered so extraordinary. It should be noted that this mission took place under difficult conditions due to competition and the lack of coordination with other teams on site that were led by Aurel Stein for the British Empire, by Albert von Le Coq and Albert Grünwedel for Germany, by Mihail and Nikolaj Berezovskij for Russia. Paul Pelliot confronted many hesitations in the direction of his mission because he wanted to avoid arriving after the other teams in order to increase the chance of new discoveries. Another challenge was his inexperience in the field of archaeology: several surveys and his first excavations at Ördeklik from 21 to 25 October 1906 proved inconclusive. Luckily, the talent of young Frenchmen eventually resolved this issue. On 29 October 1906, he discovered an important Buddhist site on the outskirts of Toumchouq and completed several other successful excavations thereafter. Today, part of the discovered material is exhibited at the Musée Guimet. It should be noted that Pelliot demonstrated a rare intellectual maturity by favouring excavations aimed at understanding the entirety of a site rather than superficial excavations focused on "museum objects”. This approach, which was ahead of its time, explains the lower archaeological “yield”.

Paradoxically, Paul Pelliot was not the first to arrive on the site of his most important discovery. Aurel Stein was the first to explore the Mogao cache during his stay in Dunhuang from 21 May to 13 June 1907, which took place 10 months before the French arrived on 25 February 1908. The English explorer's collection was substantial as it left the site with 29 cases full of manuscripts and paintings. Although he was most definitely a better archaeologist, Stein did not have the same literary and linguistic abilities as Pelliot, whose studies and previous experiences had seemed to predestine him to make the most of the discovery. From 3 - 25 March 1908, the French examined the numerous documents that dated from the fifth to the beginning of the eleventh century and were still preserved in the cave. He selected several thousand of them – manuscripts (the majority of which were in Chinese and Tibetan) and paintings - which he bought for 500 taels from the Taoist monk, Wang Yuanlu, who was the unofficial guardian of the site and invented the cave around 1900. The set is now distributed in the collection of the musée Guimet and the Bibliothèque nationale de France. An unfortunate error, however, was made: Pelliot did not make any observations on the criteria for storing documents in situ that could have informed the nature of the cache (Trombert É., 2013, p. 66). He left Dunhuang on 8 June 1908 and continued his journey to Beijing where he arrived on 4 October. He stayes in Xi’an from 23 August to 19 September 1908, during where he acquired numerous antiques, which are currently kept at the musée Guimet. He also had thousands of stampings made. They can be found at the BnF.

The mission was a complete success that definitively established Pelliot’s reputation both in the West and in the Far East. The collection has a posteriori been branded with a seal of infamy in China, and it is truly regrettable that such heritage has left its country of origin; however, it is important to remember that the French explorer had maintained good relations with Chinese authorities and intellectuals during his mission (passes, guides, letter exchanges, advices and document loans). His mastery of the language as well as his scholarship earned him a deep benevolence from local officials, a benefit that other Western explorers did not experience (Rong X. et Wang N., 2013, p. 86). He even received a gift of manuscripts from Dunhuang before accessing the site (Rong X. et Wang N., 2013, p. 98-101). In the same spirit of cooperation, Pelliot presented four of the collected documents to Chinese scholars in autumn of 1909. This event triggered an awareness of the importance of this collection of manuscripts. Like the first mention of the interest in the Mogao cache in 1903 that was written by Ye Changchi (1849-1917), this presentation is undoubtedly one of the founding events of "Dunhuangology".

After the Collection

Paul Pelliot returned to Paris on 24 October 1909. Even though his discovery in Dunhuang underwent a significant defamation campaign that questioned the authenticity of the documents, his return to France was a triumph. His consecration, however, came quickly since he was appointed professor at the Collège de France in 1911. He was only 33 years old and occupied the department chair of languages, history and archaeology of Central Asia. The rest of his career was marked by two world conflicts and his many occupations in teaching, scientific publication (BEFEO, T’oung Pao, Revue des arts asiatiques), and research communities (Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Société asiatique, Institut des hautes études chinoises). While he produced a considerable number of publications, he never published any synthesis work. Similarly, he was always interested in the materials that he collected in China, but he never explored them in depth.

Paul Pelliot had been conducting a genuine heuristic quest for 10 years whose objective was to elevate France to the top nation in the field of Asian studies. His role as a collector for Science enabled him to access primary sources that fed his thinking and helped him to progress rapidly within intellectual networks. His sensibility for texts and his superior linguistic capacities were decisive in his work and allowed him to assemble major bibliographic collections. His missions also led him to acquire archaeological pieces and works of art. The dual and complementary nature of his collections made him an important figure both in the library and museum worlds.

The result of Paul Pelliot's collections

The Pelliot collection in the Manuscript Department of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

The documents brought in France by Paul Pelliot were allocated to the BnF on 24 November 1909, and their official registration took place on 26 April 1910 (Monnet N., 2013, p. 143 et 153). The most precious set is made up of several thousands of manuscripts dated from the fifth century to the beginning of the eleventh century as well as some pre-1035 prints in Chinese, Tibetan, Kutchean, Sanskrit, Uyghur, Sogdian or Khotanese, and fragments of prints in Xixia, Mongolian and Tibetan (Berthier A., 2000, p. 93). These texts were already known but came out prior to the printed editions. Some them were on the other hand rediscovered or unknown, especially those from popular literature. One also finds documents from official, monastic or personal archives. It is a true archival collection, unique outside of China. The corpus has been divided among several language-specific collections. It should be noted that bilingual texts have been sorted into collections corresponding to the “most common” language, that is to say, Chinese, while the only Hebrew text has become part of the Hebrew collection (Berthier A., 2000, p. 93). The organisation of the collections has been refined through identification and deciphering: an on-going long-term project to which multiple generations of researchers have contributed.

Pelliot’s Chinese collection corresponds to 4039 Chinese manuscripts originating from Dunhuang (Pelliot chinois 2001-6040). His Chinese Douldour- âqour collection includes 157 leaflets and 49 fragments that were discovered during the excavation of a monastic complex; some examples come from the neighboring site Hiçar. Pelliot’s Khotanese collection is comprised of 10 manuscripts, but about 70 documents in this language are present in his Chinese and Tibetan collections. Pelliot’s Kutchean collection brings together 2000 documents, two thirds of which are fragments. His Uyghur collection holds 20 documents, 14 of which come from the Mogao cache (11 others can be found in the Chinese collection) and a certain number of texts were identified a posteriori in other collections. 363 documents in Uyghur from the Mogao cave 181 from the Pelliot Uyghur cave 181 collection (this cave is now numbered 465). The Pelliot Sanscrit collection contains 4000 fragments of which only 1000 to 1500 are usable. These come from excavations that took place at Douldour-âqour and Soubachi as well as from the Mogao cache. The Sogdian Pelliot collection includes 30 items that correspond to scrolls, sheets and fragments. The Tibetan Pelliot collection contains 2216 items plus 254 bilingual and trilingual manuscripts. The set has been collected from Dunhuang. The same goes for Pelliot’s Xixia collection: apart from one plaque found in a cave in Shuangdunzi, the 213 pieces (mostly prints) are from caves 181 and 182 (current numbers 465 and 464). One collection is dedicated to documents that originated from cave 181. Finally, a miscellaneous Pelliot collection exists that corresponds to residue awaiting treatment (Berthier A., 2000, p. 94-110).

The Pelliot A-B collection concerns a period lasting from the tenth to the nineteenth century and includes over 30000 printed booklets (reference texts, local monographs, congshu (anthologies), etc.) and some manuscripts, albums, stampings and oracular inscriptions on bone (28 fragments). This set was largely purchased in China in 1908, and it had a considerable impact on the BnF’s Chinese collection because it both doubled and completed the already existing collection (Pelliot P., 1913, p. 699). The Pelliot A collection contains 329 inventory numbers and the Pelliot B, 1745 (2074 titles in 5288 bound volumes).

The BnF also holds a stamping collection that includes 2000 references, the majority of which were made in the forest of Steles in Xi’an. This set entered the Library in 1910 (Berthier A., 2000, p. 116). After the researcher’s death in 1945, the BnF bought personal copies of the journal T'oung Pao in the 1950s. Pelliot had edited this journal for twenty years, and these copies were annotated by him (Monnet N., 2013, p. 142-143).

The Pelliot collection at the musée Guimet

Pelliot's archaeological and artistic findings have been kept at the musée Guimet since 1945. The collection had previously been kept and partially displayed at the Louvre beginning in 1910. On 12 March 1910, a room had been dedicated to the collection and was given the name of the donor (Renou, 1950, p. 135). A very interesting testimony about this room can be found in the Pelliot archives at the musée Guimet: a set of index cards presents the distribution of some 287 works brought back from Central Asia in 9 showcases (archives Pelliot, musée Guimet, Pel. Mi 80). A link to the musée Guimet, however, had been established before 1945. In 1913, 15 paintings from Dunhuang were deposited at the museum, according to Pelliot’s instructions. In 1922, 40 paintings that had been in storage at the Louvre joined them, along with the group of Chinese paintings collected in Beijing in 1900, that had been deposited at the Louvre by the EFEO in April 1904 (Gyss-Vermande C., 1993, p. 75). Paul Pelliot was also supported by the musée Guimet, which put at his disposal the apartment of the musée d’Ennery (Jarrige J.-F., 2013, p. 549), which he became the curator (Thote A., 2020, p. 147-160) in the early 1930s.

The Pelliot collection is a large and complex set (over 1400 inventory numbers); it combines graphic arts and textiles, archaeological materials, architectural elements. The collection is distributed in several departements according to the nature and/or geographical origin of the pieces (Chinese paintings, Chinese archaeology, Chinese Buddhism). The earliest collected corpus corresponds to 150 paintings that were bought in 1900 during Pelliot’s first mission in Beijing. It mainly contains liturgical or religious works in addition to 15 miscellaneous paintings (landscapes, flowers, birds, etc.) (Gyss-Vermande C., 1988, p. 106). There are two liturgical sets that illustrate the pantheon of “Water and Earth fasting” (Shuilu zhai):the first (A series) contains 33 paintings dating back to 1454, while the second (B series) includes 74, probably dating from the nineteenth century (Gyss-Vermande C., 1991, p. 96).

The rest of the collection resulted from the Pelliot mission (1906-1908). The most important set (about 400 items with 250 significant pieces and the rest in a fragmentary state) originate from the Mogao caves (Dunhuang), mostly from the cache. Covering a period from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) to the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), the set principally consists of paintings on silk and hemp (the paintings on paper are kept at the BnF), fragments of paintings and textiles, as well as 20 sculptures, mainly made of wood. Note that 951 Uyghur mobile characters were found in the same cave (181, current number 465) as the Uyghur documents kept at the BnF. The musée Guimet also holds several sets that correspond to successful excavations of Buddhist sites that were carried out by Pelliot in Toumchouq (30 October – 12 December 1906), in Douldour-âqour (17 April – 4 June 1907) and in Soubachi (11 June – 24 July 1907). The material dates to a period from the fourth to the eighth century and includes numerous sculptures or fragments of sculptures in dried clay as well as fragments of paintings on cob and pieces or fragments of works in terracotta, wood, metal, etc. Additionally, there are several much smaller sets that correspond to other excavations that revealed less material, such as at Qumtura (1- March – 22 May 1907), or surveys, such as those carried out in Khan-oi (September 1906). The provenances are indicative of Pelliot's archaeological activity from his arrival in Kashgar on 29 August 1906, which intensified during his long stay in the Koutcha region in 1907. It should be noted that a monetary treasure (MG 24490), known as the "Tajik Treasure" was deposited in the Cabinet des monnaies et médailles of the BnF in 1983, before being returned to the Musée Guimet in 2003. This treasure originally consisted of 1,300 sapèques found in a jug, 249 of which are still preserved.

Finally, a set dating mainly from the Han dynasty (206 av. – 220 apr. J.-C.) includes around 300 items that correspond to a wide range of acquisitions of Chinese antiquities (mirrors and bronze vases, stone blocks, tiles and clay vessels, etc.). These pieces were likely bought during Pelliot’s mission, but the information concerning their provenance is not very precise. Many were bought during the stay in Xi’an mission (23 août-19 septembre 1908). Finally, it is important to note that the inventory of the musée Guimet indicates that in July 1912 Paul Pelliot personally donated some of these archaeological pieces (terracotta tiles and a few inkstones), which were not initially in the Louvre.

The collection of Tibetan bronzes at the École Française d’Extrême-Orient

Since 1970, the EFEO has housed a collection of Tibetan bronzes in Paris that was mainly assembled in 1900 by Pelliot during his first mission in Beijing. The director of the EFEO mentioned in 1902 around 80 bronze statues that, in multiple aspects, represent Tibetan Buddhist art (Foucher A., 1902, p. 434). Today, the collection contains 132 pieces: 97 bronze statues, 1 lacquered wood, 27 religious objects and 7 thangkas. The statues represent divinities from the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon and the founders of the Gelug-pa sect. The set mostly dates from the nineteenth century, with the oldest pieces dating back to the second half of the eighteenth century. At first, the collection was kept at the musée Louis Finot in Hanoi and was then sent to the EFEO delegation in Phnom Penh in 1954, before being shipped to France.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne