DELAPORTE Louis (EN)

Biographical article

Naval officer, explorer, and tireless promoter of Khmer art, this son of a lawyer from Toursled a career filled with intriguing paradoxes. As a sailor, he suffered from seasickness and grew restless in this highly regulated life. By chance, he embarked on a mission of exploration in Indochina that would change his life, leading him to devote it tirelessly to Khmer art. He established further missions in order to assemble a collection and struggled to create an Indochinese museum at a time when no one in France was interested in this art. The museum, once created, with himas curator, had a turbulent history. For this reason, this enthusiastic autodidact, like others, was hardly recognised by scholarly institutions.

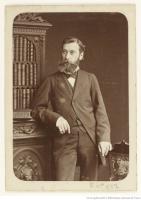

Entering the École navale of Brest in 1858 as a midshipman, then as an ensign in 1864, he made many voyages before reaching Saigon in 1866. A skilled draughtsman, he was assigned to the Mekong Exploration Mission led by frigate captain Ernest Doudard de Lagrée (1823-1868), assisted by Lieutenant Francis Garnier (1839-1873), during which he first discovered the ruins of Angkor, which fascinated him, as he recounted in his Voyage au Cambodge, published in 1880: “The sight of these strange ruins struck me, too, with keen astonishment: I admired the bold and grand design of these monuments no less than the perfect harmony of all their parts. Khmer art, resulting from the mixture of India and China, refined, ennobled by artists who could be called the Athenians of the Far East, has indeed remained as the most beautiful expression of human genius in this vast part of Asia which extends from the Indus to the Pacific […] it is, in a word, another form of beauty.” (Delaporte L., 1880, p. 10). It is worth noting the inevitable mention of classical Greece, present in so many accounts of travels in Asia, as if this detour via a known and recognised milestone in European history was essential for these unfamiliar arts to gain inclusion in the universal human community.

The mission turned into a disaster: in addition to the material difficulties, the rigours of the climate, and the hostility of certain populations, its leader, Doudart de Lagrée, died due to illness in Yunnan in 1868. “From every point of view, this loss seems irreparable: he was a man of rare goodness and great worth. He had won the affection of us all, French and native alike. His constant concern had never ceased to watch over each one of us, while his unshakable firmness had succeeded in bending the greatest resistance and leading us where so many others would have failed. He was a leader.” (Beauvais de R., 1931, p. 165) Francis Garnier took the lead of the expedition, which arrived in Saigon in June 1868, greeted by the crowd.

Back in France, the account of the expedition, owing to Garnier supported by Delaporte, was published in Le Tour du monde with photographs and drawings (1868-1869), which helped anchor this mission in the collective imagination of the French colonising efforts. Named lieutenant in 1869, then Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 1872 (LH//702/62), Delaporte nevertheless aspired only to return to Cambodia and obtained a new mission, under the aegis of the ministries of the Navy, of Foreign Affairs, and of Public Instruction (ministères de la Marine, des Affaires étrangères, de l’Instruction publique), with the financial support of the Société de géographie, with the goal of studying the navigability of the Red River and collecting "statues, bas-reliefs, pillars and other monuments of architecture or sculpture of archaeological and artistic interest" according to the Order of the Ministry of Public Instruction, Religions, and Fine Arts (ministère de l’Instruction publique, des Cultes et des Beaux-arts) of May 7, 1873 (AN F17 2359)

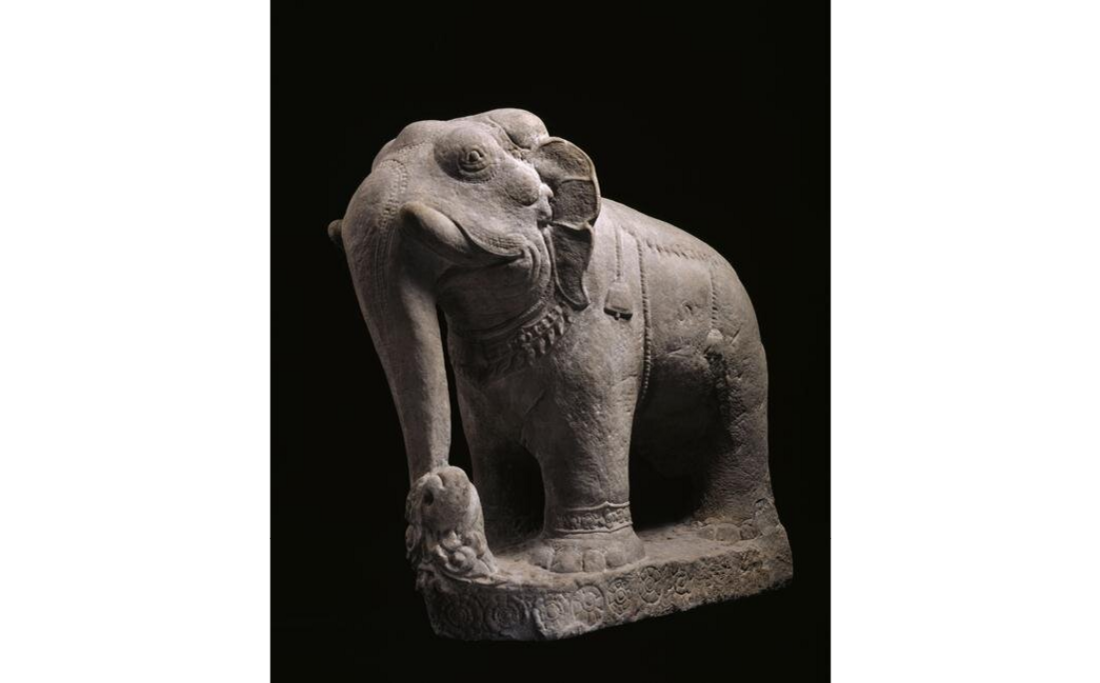

Upon arriving in Indochina in 1873, Delaporte took advantage of the rainy season to mount an expedition to the ruins of Angkor, recruiting volunteer employees to support it. His goal was to collect works of art, as he explained in his report to the Minister of Public Instruction in 1874: "I had been able to visit with the late Commander de Lagrée the ruins of Angkor and some other belonging to the Khmer era. The sight of these imposing remains made me conceive from then on the desire to enrich our national museum with some of these artistic riches of which there are as yet no specimens in Europe” (Delaporte L., 1874, p. 2517). He embarked with all the necessary equipment, official gifts, and personnel.

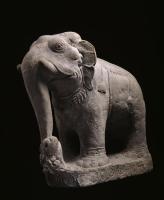

The expedition advanced on two fronts to reach Angkor and to cover as much ground as possible, facing the usual vicissitudes in the tropical forest zone. At Angkor, the team set to work, removing brush, clearing, photographing, drawing, making surveys of the ruins, taking casts. But the conditions were such that nearly all the members fell ill, including Delaporte. Loading the crates as best they could onto boats, the expedition returned to Saigon on government orders in fall 1873. Then it was back to France for Delaporte, with 102crates filled with sketches, casts and originals, including around 70 pieces of sculpture and architecture.

Delaporte was determined to show his wonders to the French public. But he had not counted on the incomprehension among the museum circles of France: the Louvre, then the Palais de l’Industrie declined the offer. Apparently, the case caused bickering between the directors of the Louvre and the Beaux-arts. The remaining optionwas the Palais de Compiègne, where he installed the collection in 1874, but conditions wereunfavourable in this“Purgatory of Compiègne”, as it was dubbed by Pierre Baptiste in the catalogue Angkor. Naissance d’un mythe. Louis Delaporte et le Cambodge: “The Château de Compiègne was not made for such a task. It had none of what is needed to become a museum. The Cambodian antiquities were inappropriately connected with a few display cases with stone axes and Gallo-Roman debris, which had belonged to Saint-Germain. Let usbe rid as soon as possible of these scientific furnishings, which clash with the official furnishingsthat have cluttered it since the First Empire. Render to Paris what belongs in Paris: the documents its workers need to understand and tie together the successive ages of these intermittent civilisations which, by replacing each other, will ultimately lead to universal civilisation” (Baptiste & Zéphir, 2013, pp. 117-118). In 1878, the reconstruction of the famous Giant's Causeway was much admired at the Exposition universelle, both by the press and by the public, proving that interest in this singular art did not await the goodwill of official authorities. But the collection was then relegated to the basements of the Palais du Trocadéro.

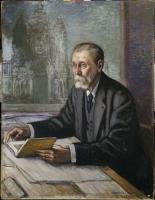

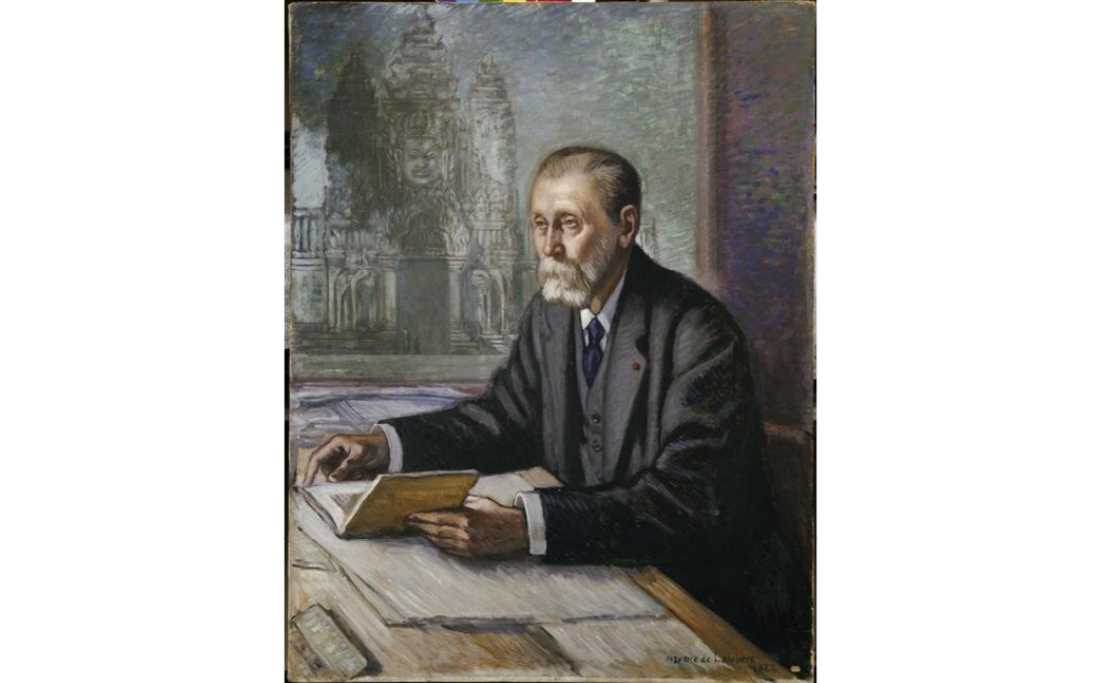

In the meantime, Delaporte wed Hélène Savard in 1876, beginning a happy marriage that broughtto his life a dedicated and financially comfortable collaborator. He retired from the army and set to work writing his Voyage au Cambodge, published in 1880; this work persuaded him that he lacked the documents needed to truly grasp the essence of Khmer art. He did not give up, despite his already fragile health, and requested a new mission from the Ministry of Public Instruction, subsidised in part by the Société académique indochinoise, to complete the museum's collections. This time, he knew he could leave nothing to chance: he carefully prepared each step, chose his collaborators, and established a work program that he could control step by step. Arriving at the end of 1881, he was quickly struck down by fever and illness, repatriated in 1882, leaving the most valiant of his collaborators to carry out the mission. Casts, photographs, and originals joined the collections stored at the Trocadéro, which were exhibited from 1882. The Musée indochinois was created almost on the sly at the Trocadéro, while Delaporte organised new missions in 1887-1888 to add to the collections of casts, despite not being able to participate himself due to his failing health,. In 1889, he was appointed curator of the Khmer collections of the Trocadéro on a pro-bono basis. The next ten years were devoted to writing his magnum opus Les Monuments du Cambodge in three volumes. He died in 1925, replaced by Philippe Stern (1895-1979), author of a thesis for the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes on the Bayon at Angkor. Between 1927 and 1936, when the museum finally closed, several exchanges took place with the Musée Guimet, which sought to create a room dedicated to Indochinese art.

The collection

Starting with the first expedition of 1873, Delaporte detailed the results of his mission in his Rapport fait au Ministre de la marine, des colonies et au Ministre de l’instruction publique: about 70 pieces of sculpture and architecture, which he described, casts, plans, elevations, and photographs "of more than 20 remarkable monuments".L’Art khmer by the Comte de Croizier included its catalogue raisonné. The collection was enriched during the following expeditions but then suffered from being tossed between Compiègne and Paris, where it was partially presented at the Exposition universelle of 1878 before being deposited at the Palais du Trocadéro. From 1927 to 1936, various movements between the Musée indochinois and the Musée Guimet attempted to offer rationales for the collections: originals at Guimet, casts at the Indochinese museum. In 1936, when the latter closed definitively, the casts were treated with complete indifference, poorly stored in various places with no concern for conservation. They were restored in extremis fora 2013 exhibition at the Musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet.

The remarkable photographic coverage of the various missions is deposited in the museum's photographic archives, along with a number of surveys and plans.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne