BILLEQUIN Anatole (EN)

Biographical article

Anatole Adrien Billequin was born in Paris, the son of François Frédéric Adolphe Billequin, a lawyer, and Joséphine Rosalie Allaize (AN (French national archives), LH 240 21). Working as a chemistry teacher in Peking, he played a very important role in diffusing Western knowledge in China in the nineteenth century, and at the same time carried out several missions to collect ceramic samples on behalf of the Sèvres Manufactory.

A chemist in Peking

He was educated in the Collège d’Harcourt (the future Lycée Saint-Louis), before studying in the laboratory of the chemist Jean-Baptiste Boussingault (1802–1887) (Cordier, H., 1894, p. 441). In 1866, after spending several years as the Head of Chemistry in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers and at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, Anatole Billequin was hired by the Chinese government to occupy the post of Chair of Chemistry and Natural History at the invitation of the English Customs Inspector Robert Hart (1835–1911) (Martin, W.A.P., 1896, p. 303; Zhang, H., 2005, p. 36). At Tongwenguan (同文館) (Tungwen College) in Peking he taught the basic principles of chemistry to third- and seventh-year students (Vlahakis, G., et al., 2006, p. 188). Aside from the fundamentals, his courses also included qualitative analyses, the principles of extracting metals through the separation of substances such as soluble sands (id. p. 188). He learned Chinese in the country and succeeded in mastering the language to such an extent that he could translate chemistry books into Chinese, which were then used during his courses. His most famous publications were the Huaxue zhinan (化學指南), Guide de Chimie (1873), a chemistry manual based on the translation of Leçons élémentaires de chimie by the Italian-born French chemist Faustino Malaguti (1802–1878), and the Huaxue chanyuan (化學闡原), Explications concernant la chimie (1882), which borrowed many elements from the works of the German chemist Carl Remigius Fresenius (1818–1897) (Zhang, H., 2005, p. 36). Billequin adopted an approach to translation that consisted of orally translating the text, sentence after sentence, in spoken Chinese, while a Chinese assistant transcribed the content into literary Chinese (Reardon-Anderson, J., 2003, p. 36). At a time when Western chemistry was gradually developing in China, the choice of the translation of the terms into Chinese was crucial. The characters he created for the translation of the chemical elements were loaded with meaning: hence, the character that described calcium consisted of the elements of metal (jin金) and the character (hui灰) for lime, which consists mainly of calcium (Reardon-Anderson, J., 2003, p. 40). His translation of the chemical elements, superseded by the work of John Fryer (傅蘭雅) (1839–1928) and Xu Shou (徐壽) (1818–1884), which adopted a phonetic translation process, had no posterity, but provided a good illustration of the issues associated with the penetration of Western sciences into the Chinese language at this time (Zhang, H., 2005). Aside from his written contributions, Anatole Billequin most probably participated in the establishment of a chemistry laboratory in Tongwenguan (Zhang, H., 2005 p. 37).

A tireless translator

Between 1879 and 1882 he took on the monumental translation of the French Codes (the Code Pénal, Code du Commerce, Code Forestier, Code d’Instruction Criminelle, and Code Civil), consisting of forty-six volumes, with the help of Shi Yuhua (時雨化), using the above-mentioned approach.

In 1891, Anatole Billequin published a Dictionnaire de Français Chinois. This publication was motivated by his desire to create a French dictionary in ‘pure Mandarin’, rather than in the so-called ‘vulgar’ spoken language, suhua (俗話), which had regional variations. He also wanted to enrich his book with ‘scientific expressions and techniques drawn from the best recently published works in the field’, and highlighted the development over recant years of a new language specifically adapted to translate the Western sciences (Billequin, A., 1891).

Missions in China

In 1874, the Minister of Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts appointed him a correspondent member of the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales (AN (French national archives) 62AJ/59). He was often in contact with the director of the École des Langues Orientales, Charles Schefer (1820–1898), to whom he sent his latest works on chemistry for the Bibliothèque des Langues Orientales (AN (French national archives) 62AJ/59). It was also through the intermediary of Charles Schefer that the Sèvres Manufactory made contact with Anatole Billequin to entrust him with a mission on Chinese porcelain (see the section below about Billequin’s collection).

Uncompleted essays & recognition

Anatole Billequin died at the age of fifty-six from heart disease, just as he was about to return to Peking (Cordier, H., 1894, p. 442). In his obituary, Henri Cordier mentioned five incomplete manuscripts he wrote: an ‘Essay on the state of the sciences in China, comprising geography, geology, mineralogy, physics and chemistry, pharmacy, medicine, surgery, veterinary art and pathology, and natural history’, an ‘essay on Chinese agriculture, comprising fertilizer, labour, taxes …’, an Essai sur la porcelainede Corée (‘Essay about Korean porcelain’) translated from the Ting tche tchene Tao Lou (Jingdezhen Taolu [景德鎮陶錄]), ‘Reports about certain Chinese theatre plays’: La Revenante, Le Pavillon de la pivoine, Le Pavillon d’Occident, L’Épingle des fiançailles, Le Ressentiment de To Ngo, translated by Bazin’, ‘Le Roman des deux Phénix’ (uncompleted), and, lastly, an annexe to the French–Chinese dictionary in the geographical section (uncompleted) (1894, p. 442, n. 2). His widow, Marie Adélaïde Cornillat, gave the Musée Guimet his notes about Korean porcelain, which were then published posthumously in the journal T’ong Pao at the request of Émile Guimet, and, as highlighted by Stéphanie Brouillet, the diplomat Victor Collin de Plancy (1853–1822) (Brouillet, S., 2014, p. 27; Billequin, A., 1896, pp. 39–46).

On 8 February 1877, in recognition of his academic work, Anatole Billequin was made an Officier d’Académie (AN (French national archives) 62AJ/59), and in 1881 was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur et Officier de l’Instruction Publique. He was also awarded several honours in Asia: a fourth-class Mandarin in China (Calendar of the Tungwen College, 1885, p. 39, Zhang H., 2005, p. 36), an Officer of the Dragon of Annam, and a Knight of the Order of Cambodia (Cordier, H., 1894, p. 442).

The collection

A mission for the Musée Céramique de Sèvres

On the recommendation of Charles Schefer, Anatole Billequin was entrusted during the year 1875 with a ‘programme (…) set up by the Sèvres commission’ on behalf of the management of the Beaux-Arts (AN (French national archives) 62AJ/59). To date, it is difficult to know the precise instructions given to Anatole Billequin for his collection. However, it is certain that the mission consisted of two elements: one was technical and the other aimed at enriching the museum’s collections. Hence, the Minister of Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts had requested that the manufactory’s administrator, its chemist Louis Alphonse Salvetat (1820–1882), and the collections curator at the Musée Champfleury each express their wishes and questions (MMNS, 4W388, letter dated 29 July 1875). A draft of a letter held in the manufactory’s archives laconically mentions the requests made for the museum: it states that ‘the instructions to give to Mr Bilquin [sic] to enrich the showcases devoted to Chinese products are more aesthetic than technical, and more general than specific’ and mentions the need to buy architectural elements, earthenware, and ancient objects; and most importantly it stresses the fact that Anatole Billequin should visit the Musée de Sèvres in order to get a good idea of the nature of his mission (MMNS, 4W388, letter dated 2 August 1875). The Minister allocated a sum of 1,000 francs to Anatole Billequin, of which 500 francs was intended to cover his travel and acquisition expenses and 500 francs by way of remuneration (MMNS, 4W388, letter dated 20 August 1875). In 1880, the manufactory decided to discontinue its funding for the mission, as the report from the meeting that issued this decision was somewhat undecided about the mission’s success: on the one hand, the Musée de Champfleury seemed to indicate that the ‘information provided by M. Billequin is insufficient’, and on the other, that he ‘was successful to some extent’, and lastly the report concluded that ‘there is little point in allocating this mission budget to Mr Billequin, unless he is capable of providing some useful manufacturing information’ (MMNS, 4W388, Billequin file, meeting at the Musée held on 16 May 1880).

Giving names to Chinese colours

Between 1876 and 1878, Anatole Billequin sent three shipments to the Sèvres Manufactory, each of which was accompanied by an inventory that described the objects, their prices, and, in most of the cases, the Chinese names. The first shipment was inventoried and classified by Édouard Gerspach (1833–1906), who was director at the time of the national manufactories (inv. nos. MNC 7329 to MNC 7395). The latter created a classification by colours, then according to the place of production, and published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts two articles from his ‘Notes sur la céramique chinoise’ (1877, pp. 225–238 and 1882, pp. 44–54). The result of the first shipment was, as Gerspach put it, to know the terms used to designate colours in China, by systematically associating an object with a Chinese term, which would then be translated. He discovered, for example, that the term ‘orange peel’ did not designate a colour but rather the granularity of the glaze (Gerspach, E, 1877, p. 228). He also discovered that the term ‘sang de bœuf’, used in France to designate copper red glaze porcelains, had no equivalent in China, where this kind of object was called jihong (霽紅) or Lang yao (郎窯) (Gerspach, E, 1877, p. 229). Lastly, certain colours seemed to make their first appearance in French collections: Gerspach mentioned, in particular, ‘eel skin yellow’ (shanyu huangyou [鱔魚黃鈾]), and the colour ‘mule liver, horse lung’ (lügan mafei you [驢肝馬肺釉]) (Gerspach, E, 1877, pp. 230–131). In addition to this ensemble intended to create a nomenclature of Chinese colours, Billequin brought back a series of objects designed to be used in everyday life, which he purchased for very reasonable sums. They came from various regions, from Cizhou 磁州, the province of Shandong (山東), and that of Yixing (宜興). The last part of the shipment comprised several varnished tiles decorated with en ronde-bosse (‘in the round’) animals. Gerspach concluded that it was important to assess this initial shipment ‘only from a technological viewpoint, which is all that was sought; from this perspective, it is excellent and constitutes a solid working base’. In the second article by Édouard Gerspach, published in 1882, and which included Billequin’s last two shipments, the author continued with his assessment of Chinese colours, focusing successively on douqing (豆青) ‘pea green’, ‘which may be ideal for our French ceramicists, who are looking for a ground onto which they can apply their pastes’; jiepizi (茄皮紫) ‘aubergine purple’, ‘a very famous colour, lauded all the time by the travellers, but whose reputation we think is particularly overrated’ (p. 46); and ‘shimmering black’ wujin (烏金) or wujing (烏鏡), ‘an object much sought after by French collectors’ (p. 52), etc. The crackled glaze, suiqi (碎器) , a process ‘of an extreme simplicity in theory’, but which no European producer had managed to reproduce on porcelain, took longer to develop (Gerspach, E., 1882, pp. 50–52), although the author made no specific statement about how to obtain this effect.

A technical collection

Anatole Billequin willingly acquired damaged porcelain objects at a low price, because their decorative elements were of interest to the Sèvres Manufactory. In his inventory of the second shipment, he mentioned, for example, a vase with a cut neck that he acquired for the modest sum of 50 francs, described as follows: ‘A vase in the form designated by the word kuan [guan (官)] whose neck has been cut; despite this fault I found it interesting for several reason. Its colour is one of those that would be of interest to Sèvres. The crackled purple enamel with which it is decorated explains the term liou yao [liuyou (流釉)] (flowing enamel), which is certainly the process used for its fabrication. This process involves applying a certain quantity of thick enamel to the upper section of the vase, which flows when heated onto the main body of the ground enamel, with which it merges, producing more or less strange effects. This vase will be useful for studying the veins. The crazing on its enamel gives us an idea of what the Chinese means by yu tze wen (魚子文) (yuziwen (魚子紋)) crazing, which resembles fish eggs’ (MMNS, 4W388, inventory of the 2nd shipment, March 1877, no. 31, inv. no. MNS 8018).

Korean porcelains

Anatole Billequin did not limit himself to collecting products requested by the Sèvres Manufactory, and took a close interest in the subject of Far-Eastern porcelain, by tackling one of the most controversial issues of the times—the geographical origin of the porcelains. A certain number of nineteenth-century French authors had suggested that this had been invented in Korea (particularly, Jacquemart, A. and Le Blant, E., 1862), while others insisted that the country had never produced any porcelain at all. Billequin cast doubt upon this assertion when he acquired in China, thanks to intermediaries in contact with Korean embassies, samples from the country, which he immediately shipped to the Sèvres Manufactory (Billequin, A., 1896, p. 41). He consulted several ancient sources, in particular the study by the sinologist Léon d’Hervey de Saint Denys (1822–1892) on the Wenxian Tongkao (文獻通考) by Ma Duanlin (馬端臨) (1254–1322), with the aim of finding out if the Korean porcelain had once been used for tributes to China (Hervey de Saint-Denys, L., 1872). Yet, as none of the consulted documents mentioned this, he concluded that Korean porcelain must have been too poor in quality to be used as a tribute (Billequin, A., p. 43). He then found the mentions of Korean porcelain in two Chinese books on ceramics, the Tao Shuo (陶說) and the Jingdezhen Taolu (景德鎮陶錄), in which Korean porcelain was sometimes described, often viewed as of little interest and, in the best of cases, compared with the Longquan celadons (龍泉). Billequin concluded his essay as follows: ‘All the research confirms the mediocrity of Korean products, which are completely different from the fantastical descriptions of certain European authors. As for their antiquity, it seems to be evident that Korea borrowed the techniques from China and transplanted them in Japan’ (p. 46). Stéphanie Brouillet identified, amongst the lots of Korean porcelain shipped, several high-quality objects, in particular a white porcelain keg, as well as a celadon bottle that probably also dated from the Goryeo period (918–1392) (Brouillet, 2014, pp. 17–18, cat. nos. 80 and 84).

Anatole Billequin’s library

The only known sale associated with the name Billequin is that of his collection of books, which was dispersed after his death in 1895. The various sections in his library attest to his curiosity, which involved the study of Chinese culture as a whole. There were several works on ceramics: the Histoire et fabrication de la porcelaine chinoise by Stanislas Julien, the Catalogue of a Collection of Oriental Porcelain and Pottery by Augustus W. Franks; books on the Chinese language, as well as the dictionaries of Samuel Wells Williams (衛三畏 [1812–1884]), Chrétien Louis Joseph de Guignes (1759–1845), Séraphin Couvreur (1835–1919), and so on; several translations of Chinese literary works, treatises on the history and geography of China, travel accounts, several volumes of the Journal of the Peking Oriental Society, and the Custom Gazette; his Chinese language library was no less rich and heteroclite: it embraced themes such as Buddhism, botany, literature, calligraphy, coin collecting, and so on, certain works were annotated or partly translated by Anatole Billequin.

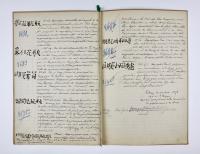

Anatole Billequin in French public collections

In addition to the shipments to Sèvres, Billequin’s name also featured in the inventory books of the collector Ernest Grandidier (1833–1912), which explains the presence of some of the works he brought back in the collections of the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet. The Département des Manuscrits Orientaux also holds a manuscript brought back by Anatole Billequin (ref.: CHINOIS 11965), which consists of a volume of ninety commonly used Chinese phrases, which were probably used to learn Chinese. The same department also houses examples of his translations, some of which were dedicated by Anatole Billequin to Charles Shefer: there are all the volumes of the French Codes (法國律例) in an edition dating from 1880 (The Code Civil [民律], reference: CHINOIS 2443–2464, the Code Pénal [刑名定律刑律], reference: CHINOIS 2465–2472; [民律指掌], reference: CHINOIS 2473–2480; the Code du Commerce [貿易定律], reference: CHINOIS 2481–2486; the Code Forestier [園林則律], reference: CHINOIS 248–2488), and the Huaxue zhinan [化學指南], reference: CHINOIS 5666–5667).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne