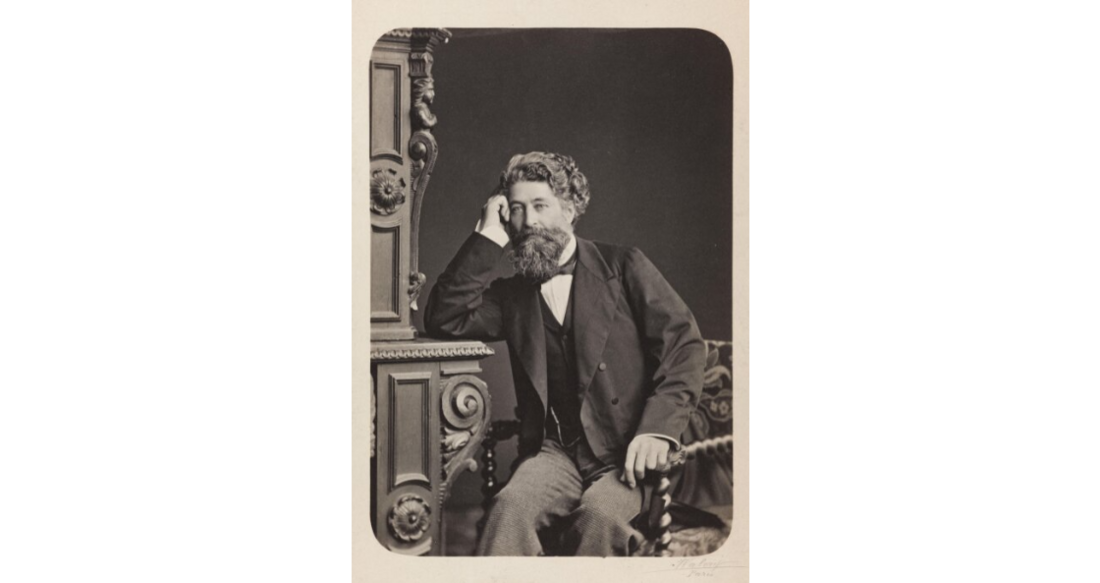

CERNUSCHI Henri (EN)

Biographical article

The hero of the Risorgimento (19th-century movement for Italian unification), and an economist and brilliant expert in international finance, Henri Cernuschi was one of the most important figures of Parisian intellectual life at the end of the nineteenth century.

Cernuschi was born in Milan on 10 February 1821. His father, Claudio (1792–1834), was a small entrepreneur who came from Monza, and who married Giuseppina Della Volta (1799–1840). His father died when he was thirteen and he lost his mother at the age of eighteen. He had a sister, Erminia (1823–1910), and two brothers, Costantino (died in 1905) and Attilio (who died in 1844 at a very young age). Cernuschi was initially educated at the Collegio dei Padri Barnabiti in Monza, known for its austerity, and continued his studies in Milan, with a focus on the sciences (Leti, G., 1936, p. 13).

Thanks to the support of his maternal family, he trained in public and private law at the University of Pavia, where he completed his master’s degree on 23 December 1842. On 24 April 1846, after a long period of learning, interrupted by many trips to Italy and abroad (France, England, Germany, and Holland), he was granted his license to practise as a lawyer at the Court of Milan (Leti, G., 1936, pp. 14–15).

A committed republican federalist, Cernuschi was active very early on, both on the barricades and in propaganda journalism, collaborating for example with the satirical journal Spirito Folletto, under the pseudonym of ‘a Carlist’. In 1848, with Carlo Cattaneo (1801–1869), Cernuschi was one of the heroes of the ‘Five Days of Milan’ against the Austrians, becoming a member of the War Council, which formed the basis for the provisional government. After travelling to Switzerland, to Lugano, followed by Genoa and Florence, where he participated in local democratic movements, he went to Rome. Here, he was elected a Member of Parliament at the Constituent Assembly, playing an active role in the Republican revolution. After the capture of Rome by the French, Cernuschi was arrested in Civitavecchia and incarcerated (Leti, G., 1936, p. 57). Twice tried and acquitted, he was banished to France on 1August 1850. His early days in Paris were very difficult. After giving private Italian language lessons for a while and working as a copyist for the scholar François Arago (1786–1853), in 1852, Cernuschi obtained modest employment in the Crédit Mobilier, where he was swiftly promoted, and became a member of the Board of Directors. He worked for this bank until 1858, the year when Felice Orsini (1819–1858), who was also a member of the Roman Constituent Assembly, was executed, after attempting to assassinate Napoleon III. Several days before his death, Orsini assigned Cernuschi as his testamentary executor (Leti, G., 1936, p. 123).

In 1859, Cernuschi launched into the retail sale of packaged meat, and opened three outlets in Paris, operating under the trade name Entreprise des Boucheries Nouvelles. Unfortunately, this activity turned out to be a disaster and at the end of the third year the cooperative was wound up. His business acumen at the Bourse began to reap results as of 1860. Much appreciated in the milieu of high finance for his theories, Cernuschi was entrusted with managing major bank transactions in London and Tunis (Leti, G., 1936, p. 127, 141).

In 1865, Cernuschi published his first scientific work, Mécanique de l’échange, which became a fundamental reference work in the field of finance, aside from his studies of the bimetallic monetary system that advocated two standards—gold and silver. Several years later, in 1869, he became one of the three founders and directors of the Banque de Paris. The future Parisbas emerged from the 1872 merger of the financial establishment with the Nederlandische Credit en Deposito Bank of Amsterdam. Thanks to growing profits, he soon amassed a large fortune (Leti, G., 1936, p. 142).

On 1 May 1870, Cernuschi left Paris and settled in Geneva, after being expelled from France as a result of his support for the anti-plebiscitary cause, which would have consolidated the parliamentary Constitution of the Imperial government. He returned to Paris on 4 September to attend, with great emotion, the proclamation of the Republic. His biographer reproduced the telegram he sent after the ceremony: ‘Having arrived in the morning, I attended the founding of the Republic at the Hôtel de Ville. There was perfect concord, no disputes. A new era has begun!’ (Leti, G., 1936, p. 164–165). His involvement in the Franco-Prussian War, during which he provided food for the French soldiers, was rewarded by the fact that, despite defeat, France remained republican, which prompted him to apply for French naturalisation on 29 January 1871.

Cernuschi left the Banque de Paris in 1870, although he was still involved in business, as he had a majority share in the paper Le Siècle, whose collaborators included Émile Zola (1840–1902) and Jules Castagnary (1830–1888). At LeSiècle, whose articles enabled him to promote his political and economic ideas, he struck up a friendship with Gustave Chauday (1817–1871), the assistant to the Mayor of Paris and the paper’s Editor-in-Chief, who was shot on 23 May 1871 during the Paris Commune. Cernuschi, who had gone with Théodore Duret (1838–1927), an art critic and collaborator at LeSiècle, to the prison of Sainte-Pélagie to request Chauday’s liberation, was almost murdered himself (Leti, G., 1936, pp. 179–180).

Chauday’s tragic death, which affected him and his friend Duret for the rest of their lives, may have prompted his trip to the other side of the world, to East Asia, undertaken in July 1871.

Upon his return to Paris in 1873, Cernuschi bought the last parcel of land on the Avenue Vélasquez and entrusted the architect William Bouwens van der Boijenla (1834–1907) with building a mansion that would house his collection of Asian art, and which eventually became the museum named after him (Henri Cernuschi (1821–1896): Voyageur et Collectionneur, 1998, p. 35).

An inveterate traveller, Cernuschi took business trips to Tunisia, England, and Germany, but he also visited Greece in 1863 and, later, as of 1880, Sweden, Norway, Algeria, Spain, Portugal, Russia, Italy, and Argentina, in particular to attend international conferences, in which he took part as an eminent economist. Between the end of 1876 and the beginning of 1877, he stayed for several months in the United States to disseminate his theories about bimetallism, of which he became the leading apostle.

Cernuschi passed away in Menton on 12 May 1896 at the age of seventy-five. His ashes were buried in Paris, in the Cemetery of Père-Lachaise (Leti, G., 1936, p. 276).

The trip to Asia

After the sudden death of their friend Chauday, Cernuschi and Duret decided to leave Paris and take a long trip to Asia.

On 8 July 1871, the two friends boarded a ship in Liverpool to take them to New York. After a seven-day train journey, they reached San Francisco, where they boarded the Great Republic for a twenty-four day journey to Japan. They disembarked at Yokohama on 25 October 1871. They began their stay in Japan, which lasted for just over two months, with a visit to Edo (present-day Tokyo), where Cernuschi purchased objets d’art. Accompanied by Duret, he then visited Hyōgo (Kōbe), followed by Ōsaka, Nara and Kyōto, and Nagasaki. They were granted a special authorisation to visit Nara and Kyōto, which could only be reached in a sedan chair. In the ancient capital, Cernuschi and his friend devoted themselves to cultural activities, in particular to visiting temples (Lefebvre, E., Moscatiello, M. et al., 2019, pp. 16–19).

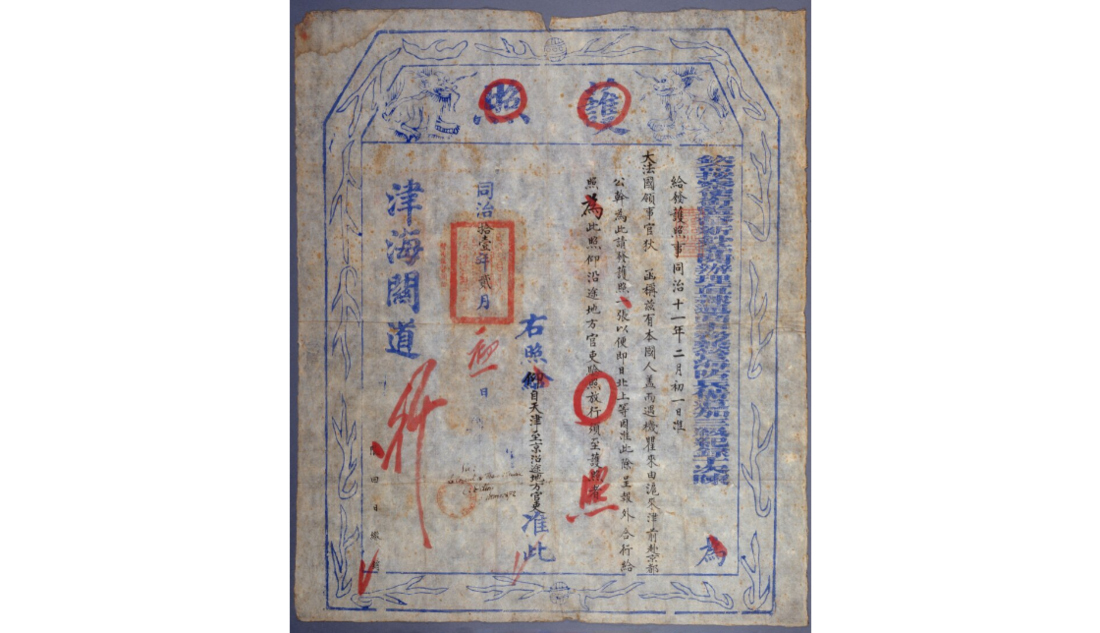

They visited China between February and June 1872. They disembarked in Shanghai. They sailed up the Blue River to Nanking, then the Yellow River to Peking, and stopped at Yangzhou and Tianjin along the way. They visited the Great Wall, which Duret likened to an opera set. The tour to Jehol was combined with a long trip to Inner Mongolia, probably one of the most adventurous episodes of the trip. Between June and August 1872, Cernuschi and Duret went to Batavia (Jakarta), to Bandoeng (Bandung) and Yogyakarta, and they also visited the plateau of Dieng and Borobudur. In August they reached Ceylon (Sri Lanka) by boat. They initially stayed in Colombo and Kandy, then focused on exploring Buddhist sites such as Dambulla and Polonnāruwa. They made it to the ancient capital of Anurādhapura, after crossing the forest.

Cernuschi and Duret visited the last country on their trip, India, between September and December 1872, on picturesque carts drawn by oxen. They made their way from Madurai to Calcutta, visiting along the way Tanjore (Thanjavur) and Madras; they continued on to Benares (Vārānasī), Āgrā, and Delhi. After crossing Rājastān, they arrived in Bombay and Ellorā, which marked the end of their Asian adventure (Lefebvre, E., Moscatiello M. et al., 2019, pp. 19–21).

This voyage to Asia may have also given Cernuschi an opportunity to study the economy and financial systems of the countries he visited, but, most importantly, it represented the beginning of his activities as a collector. In a letter to his friend, the economist Tullio Martello (1841–1918), dated 11 May 1873, several months after his return to Paris, Cernuschi revealed: ‘I did not want to focus on business matters in this country, but rather to devote myself to artistic things and I now have a large museum of Japanese and Chinese bronzes, the latter of these being very ancient’ (Leti, G., 1936, p. 184).

The collection

The will drafted by Cernuschi on 23 January 1896, about four months before his death, mentioned the bequest of his mansion located at 7, Avenue Vélasquez, and the collections of Asian art he stored in Paris. Upon the death of the collector, there were around 5,000 objects in his collection (AN (French national archives), AND/LIX 909).

It was very probably during his trip to Asia that Cernuschi began to compile his collection, as mentioned by the Baron Pierre Despatys (1838–1918) in his presentation about the museums of the city of Paris ‘(…) the travellers did not set out with an obsessive desire to collect objects and one could almost say that it was almost quite by chance that the collection began to be compiled’ (Despatys, P., 1900, p. 57). This theory about the initial phases of the collection’s compilation was also advanced in Théodore Duret’s memoirs: ‘Like everyone else, we began without a specific goal or bias, taking things quite by chance, but we were soon drawn to the bronzes. We soon realised that that they were worthy of exploration’ (Duret, T., 1874, p. 20).

With regard to the purchases made in Japan, Duret informed readers about the role played by an intermediary, a certain Yaki, who became an essential negotiator with local dealers: ‘Every day at Yaki’s, bronzes were brought in their hundreds. We sorted through the objects, a lot, agreed on a global price, and our collection increased at an extraordinary rate’ (Duret, T., 1874, p. 21). One of the most surprising pieces acquired near Edo, in the small Banryuji temple, was the monumental statue of Buddha Amida, which was more than four metres high, and is still considered an emblematic piece in the Musée Cernuschi. With regard to this wonderful purchase, Duret continued his account, specifying: ‘seeing our insatiable appetite and, above all, realising that the larger the objects the more we were attracted to them, the people who were searching on our behalf took us to Meguro, in the suburbs of Yedo; in the middle of the market gardens, they showed us an enormous Buddha. There used to be a temple here, but a it was destroyed by a fire, and for many years the abandoned Buddha was hidden from sight amongst the trees and thatched cottages. For the collectors, it was a priceless discovery, and bringing it back was a veritable exploit’ (Duret, T., 1874, pp. 21–22). This acquisition was made possible by the exceptional political situation in the country: the infighting and the restoration of the Meiji emperor.

Having collected a significant number of bronzes in Japan, Cernuschi continued his search in China. Here, the acquisitions were made differently, according to Duret, who wrote: ‘In Peking, we cannot proceed as we had done in Yedo, where we purchased bronzes by the hundreds and en masse. We have to acquire our objects one at a time, after much bartering, and one always ends up paying a high cost for them. First of all we acquire everything we can in the shops, then by gradually raising the prices we manage to purchase very rare pieces from private individuals, which enables us to compile a far more comprehensive collection’ (Duret, T., 1874, p. 122). In China, in contrast to Japan, Cernuschi was able to buy ancient specimens, whose cost was considerable. In a letter sent to Édouard Manet (1832–1883) on 5 October 1872, on board the ship Peking, Duret told his painter friend: ‘Cernuschi returned from Japan and China with a collection of bronzes, the like of which has never before been seen. I can assure you that there are objects that will astound you!’ (Inaga, S., 1998, p. 89).

During his stay in Asia, Cernuschi shipped around 900 crates to Paris, mostly containing bronze objects and sculptures (Buddhist sculptures, vases, incense burners, and okimono), ceramics, as well as lacquered carved wooden objects, paintings, prints by contemporary artists such as Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), illustrated books, and photographs, including various works by Felice Beato (1832–1909) and Samuel Bourne (1834–1912). According to the invaluable accounts of Duret and the writer and art critic Philippe Burty (1830–1890), the ensemble—which was impressive for its epoch—of around 5,000 objects, acquired mainly in Japan and China was constantly enriched in Europe. Indeed, Cernuschi shared with other collectors the excitement of the sales at auctions, in particular in the 1880s. He also purchased items from famous contemporary dealers, such as Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), as attested by the labels that are still glued to various works (Lefebvre, E., Moscatiello, M. et al., 2019, p. 22).

Furthermore, a significant part of the collection of Japanese ceramics came from the collection of Ferdinando Meazza (1837–1913), the owner of a silk factory in Milan, who, as of 1867, stayed in Japan on several occasions, and who is believed to have sold his collection to Cernuschi in 1875 (Moscatiello, M., 2019, p. 49).

Amongst the acquisitions that enriched the collection after Cernuschi returned to Paris were two admirable objects: the first was an impressive lacquered and gilt wooden tiger, bought in around 1884 from Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), who was obliged to sell it for financial reasons, according to the memoirs of Edmond de Goncourt (Goncourt, E., and J., 2004, Vol. II, p. 1124).

The second item, a fine specimen of traditional Japanese architecture around twelve metres in length, used as a balustrade in the glazed room on the first floor of the mansion on the Avenue Velasquez. This monumental object was given to Cernuschi by Sosthène Paul de Turenne d’Aynac (1842–1918), the French chargé d'affaires in Japan, at some point after the museum was set up (The Musée Cernuschi’s archives, Paris).

Very surprising was Cernuschi’s purchase of another Milanese collection, this time of Western art. On 13 April 1873, Cernuschi signed a contract to purchase the collection of the lawyer Michele Cavaleri (1813–1890), exhibited as of 1871 at the Palazzo Busca, Corso Magenta, in Milan. This ensemble, comprising more than 63,000 ancient and modern works, including archaeological finds, drawings, paintings, rare manuscripts, illuminated manuscripts, and bronzes, was transported in five train wagons to Paris. After Cernuschi’s death, the Cavaleri Collection was dispersed by his brother Constantin, who was designated as the universal legatee, at two sales, the first of which was held in 1897, for which there is unfortunately no catalogue, and the second, comprising 144 pictures, in 1900, in the Galerie Georges Petit (Davoli, S., 2008, p. 217).

Upon his return to Paris, Cernuschi presented his collection at public events. A large number of objects, including no less than 500 bronzes, was exhibited between August 1873 and January 1874, in the Palais de l’Industrie during the first International Congress of Orientalists. The Japanese bronzes, in particular the Buddhist sculptures, animals, and vases, which predominated, were an extraordinary success with the general public and the critics. Albert Jacquemart (1808–1875) mentioned the role played by Japanese objects in the presentation: ‘As one makes one’s way through the rooms in the Palais de l’Industrie one is gripped by a secret emotion; there is something particularly mysterious about these Japanese objects, whose size and boldness dominated all the others (…)’ (Jacquemart, A., 1873, p. 447). In his account of the exhibition, Louis Gonse (1846–1921) shared Jacquemart’s enthusiasm: ‘The Japanese bronzes are on the left. They are more impressive than the Chinese bronzes due to the suppleness, elegance, and simplicity of their forms, the purity of their materials, the unparalleled beauty of their patinas, and the style of their chasing’ (Gonse, L., 1873, not specified).

Other objects that came from the Cernuschi Collection were presented at the retrospective exhibition of metal held at the Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts from July to November 1880.

The bronzes in the Cernuschi Collection also attracted the attention of Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896), who was still highly critical of Cernuschi, who, after attending a dinner in the home of the Italian financier, noted on 1 July 1875 in his Journal: ‘amongst the bronzes are marvels—marvels that seem to be the most ideal examples of what the learned taste and art of their manufacture can produce. Some of the vases transcend industry and are creations of pure art’ (Goncourt, E., and J., 2004, Vol. II, p. 651).

Louis Gonse and Maurice Paléologue (1859–1944) illustrated their works on Japanese and Chinese art using many examples from the Cernuschi Collection. Considering them as precious sources of inspiration, Émile Reiber (1826–1896), the artistic director of Christofle, presented a large range of them in his album published in 1877, intended for craftsmen and designers (Moscatiello, M., 2019, p. 52).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne