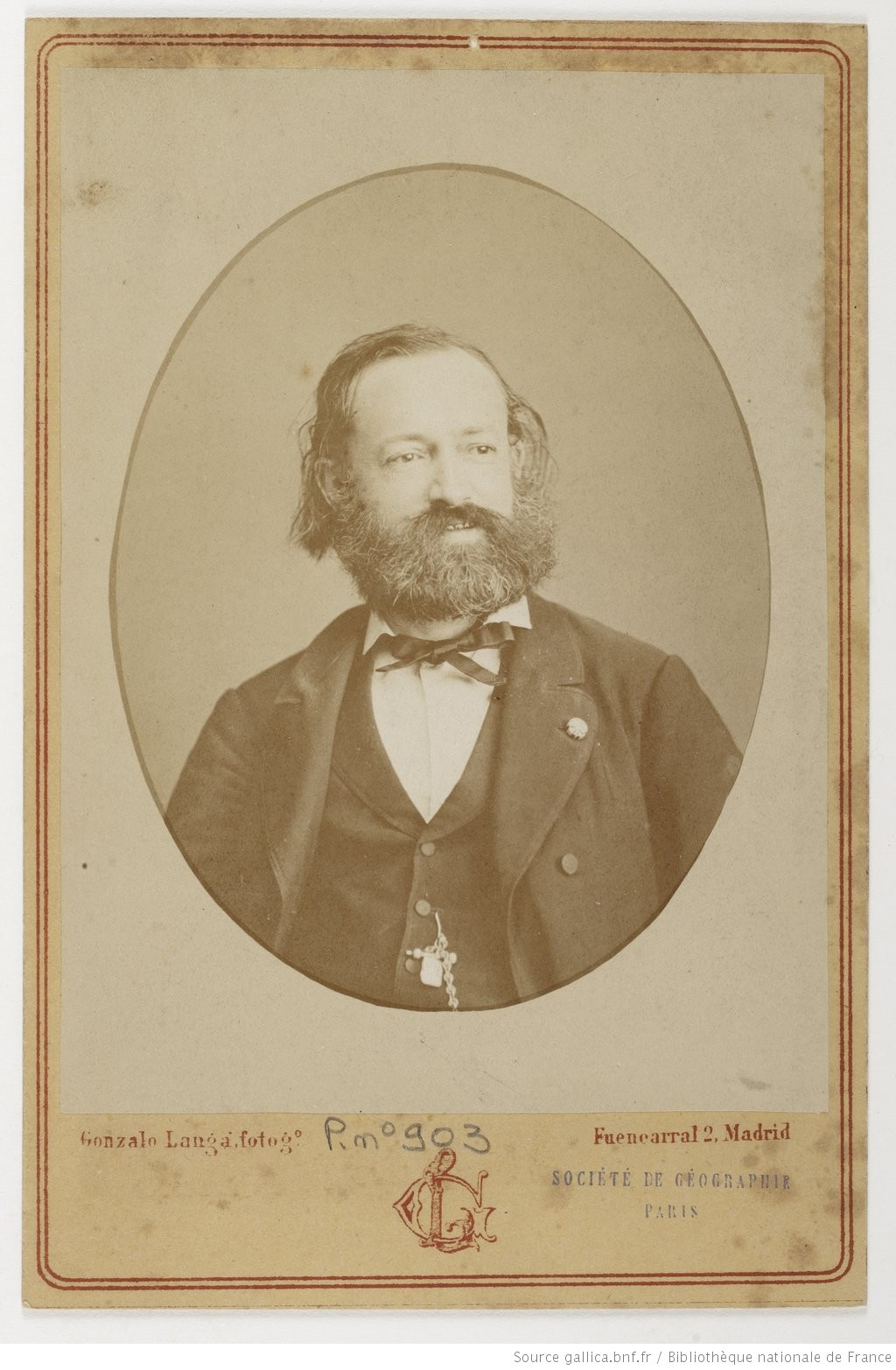

ROSNY Léon de (EN)

Biographical Article

Long relegated to the shadows of the history of French studies of Asia, Léon de Rosny (1837-1914) has been noticed again in recent years by several biographical works (Berlinguez-Kōno N., 2020; Chailleux L., 1986 and Fabre-Muller B., 2014). Several popular articles are also devoted to him in the prosopographical database of the École Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE) (Mongne P., 2018) and on Gallica ("Léon de Rosny", Gallica).

Léon de Rosny thus appears to us today not only as the pioneer of Japanese studies (as an autodidact he had frequented the Japanese as of 1852) but also as a scholar with widely open interests, spanning Asian and American civilisations, and diverse activities. In addition to his academic activities in the fields of orientalism and ethnography and para-academics (his courses on Buddhism were a remarkable success from 1890 to 1897), he was a typographer, printer, interpreter, playwright, and philosopher. His monumental work reflects this remarkably curious spirit. A scientist with indefatigable energy, his name was associated, alongside his academic duties, with numerous learned societies created throughout his long life (the Société d’ethnographie de Paris in 1859 and the Alliance scientifique universelle in 1877; he also created the first International Congress of Orientalists in 1873). He even founded, in the last decade of the 19th century, an "École du bouddhisme éclectique" with resounding echo in the press.Without entering into too much detail regarding the multiplicity of eclectic facets of the character of Léon de Rosny, a scholar with the airs of Balzac, nor the intimidatingly rich career path already described by his biographers, let us here emphasise that Rosny was a guiding light for French studies of Asia for more half a century, from the second half of the 19th century to the first decade of the 20th century. While a chair in Japanese was created for him at the École spéciale des langues orientales vivantes in 1868, after having taught this language since 1863 (i.e. after the introduction of the teaching, with its complex history, of Tibetan, but before the languages of Indochina), he quickly became famous as an authority on Asian civilisations, as evidenced by his appointment to the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, V section, in 1886 as director of studies for the conference of “religions and civilisations of the Far East and of Indian America.” While he was a pupil of Stanislas Julien (1797-1873), a central figure in French sinology, he was also a student of Philippe-Édouard Foucaux (1811-1894), with whom he learned Sanskrit and assimilated some elements of Tibetan. Examination of the subjects covered in his courses (Annuaires de l’École pratique des hautes études) demonstrates the diversity of themes and geographical areas covered. Thus appears the little-known fact that he was the only one in Paris, excepting Philippe-Édouard Foucaux with his courses at the College de France officially dedicated to Sanskrit literature, to be given elements of Tibetan in connection with his courses on Buddhism, from 1889 to 1893, then from 1900 to 1905, which became the flagship subject of his teachings during this period. In 1905, it was Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935), who had been his student at the EPHE, who made Tibetan the second part of his teaching, seemingly at the request of the followers of his course, particularly Louis Finot (1854-1935) and Joseph Hackin (1886-1941) (Annuaires de l’École pratique des hautes études). This also means that many scholars in Asian studies were trained by his contact, including Sylvain Lévi and Émile Burnouf (1821-1907) (AN, 62/AJ/23/). Famous figures such as the anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus (1830-1905) or the occultist writer Maurice Largeris (1865-19...) were also part of his teachings (AN, 20190568214, year 1893-1894). Alexandra David-Neel (1868-1969) also appears in the registers of the two schools as an auditor of Rosny's courses in 1892-1893, the year when Rosny's lecture at the EPHE in the first semester focused on the "history of the origins of Taoism" and the "religious doctrines of the Chinese anarchists" and, in the second semester, on the "beliefs of the Siamese Buddhists", subjects which clearly influenced the first steps of Alexandra David-Neel in her research on Asia (Thévoz S., 2019, p. 31-32). Although this filiation hardly appears in his work, David-Neel maintained a lasting relationship of trust with Rosny who introduced him and gave him his support in the various learned societies of which he was a member. With Alexandra David-Neel, we must finally mention a last figure of importance in these years among those close to Rosny, namely Jacques Tasset (1868-1945), who played the role of intermediary in the meeting of the two personalities mentioned. Like David-Neel, Tasset was a member of the Theosophical Society, in regards to which Rosny repeatedly positioned himself in the press on the subject of European "neo-Buddhism" (Bibliothèque municipale de Lille, Fonds Léon de Rosny, ROS-210). Rosny also defended the idea of the anteriority and the influence of Buddhism over Christianity (Rosny L., 1890, see also Rosny L., 1901b), an idea then in vogue, as evidenced by the publication in 1894 by Nicolas Notovitch (1858-19...), La Vie inconnue de Jésus-Christ. However, it is undoubtedly in reaction to the "esoteric Buddhism" defended by the theosophists, which he rejected, that Léon de Rosny conceived his "École du bouddhisme éclectique" (Rosny L., 1892, Bourgoint-Lagrange, 1899, Lawton F. et al., 1892), through which he aims for a rational philosophical synthesis with explicit Cousinian and Comtian resonances (Thévoz S., 2017, p. 19-21). Within the work of the author, the "school" is in line with philosophical and epistemological considerations inspired by the "experimental method" of Claude Bernard (1813-1878) that Rosny had conceived in 1862, exhibited in 1879 in Le Positivisme spiritualiste: de la method conscientielle (Rosny L., 1879) and repeated the following decade La Méthode conscientielle: essay de philosophie exactiviste (Rosny L., 1887).

In fact, since the early 1890s, Rosny had been surrounded by a core of students from several generations attracted to Buddhism, including Jacques Tasset, Edmé Gallois, Eugène Louveau (1848-...) Frédéric Lawton (1856-...), Gabriel Eloffe (1827-…), Pierre Paul Jean Marie Bourgoint-Lagrange (1871), René Worms (1869-...), Désiré Marceron (1823-…), and even his Japanese tutor, Seizō Motoyoshi (1866-19…). In the correspondence that he maintained with Élisée Reclus between 1894 and 1902, in which their common centres of interest can be read between the lines, approached from divergent ideological perspectives, on April 26, 1902 Rosny confides regarding this subject: "Feeling that I am at the end of my career, I no longer have any other ambition than to see some of the ideas to which a certain importance has been attached taken in hand by men capable of pursuing their development; for I am only preoccupied with one thing now, that of finding myself successors in the path on which I have embarked. The Société d’ethnographie, which I founded in 1859, has passed into the hands of a few worthy men whom I wish in the highest degree to support to the extent of the forces which still remain to me, at the expense of the re-establishment of my health, which was quite compromised last year by constant overwork [sic] from which it is impossible for me to escape.” (BnF, NAF-22914, f° 362)

Highly active in learned societies in Paris and particularly within the Société d'ethnographie, Rosny's faithful disciples of the last decade of the century carried the manifestations of the master’s multiple interests without any of them subsequently leaving a lasting trace. They are nonetheless the witnesses and actors of a significant period in the history of intellectual and spiritual exchanges between France and Asia. Almost ten years after the beginnings of Parisian Buddhism at La Rosny, Bourgoint-Lagrange, "abbreviator of the doctrine of eclectic Buddhism" and apologist of the "conscientious method" (Bourgoint-Lagrange, 1902), returned to the phenomenon:

“Lately there has been a lot of noise about the newly organised Buddhist School in Paris. Most newspapers and magazines have told their readers about this creation, and the foreign press has been moved by it as far away as Sumatra. Ladies in particular have been passionate about this doctrine, in a way that recalls the fervour of the holy women of Golgotha. Several of them did not hesitate, in order to become fully immersed in Buddhist philosophy, to devote themselves to the thankless and laborious study of the languages of the Far East. The leader of Neo-Buddhism or Eclectic Buddhism is M. Léon de Rosny, a well-known personality, famous in the world of letters and scholarship. […] He was credited with the desire to found a Buddhist church in France, something like the Gallicanism of Çâka-mouni. And already the imagination of the Parisians saw him at the head of a bonzerie, head of ascetics spoiled in the contemplation of the end of their noses, for whole years, without any concern for food or cleanliness. Others lent him the secret aspiration to a papacy and made him a pretender to the role of Dalai Lama or at least to a similar role. For us, without claiming to pose as champions of the doctrine of M. Léon de Rosny, we declare, after having attended a large number of his conferences and read his books that the morality preached by him is highly worthy of being known, and that, by its purity, it deserves to be deeply respected. As for the personal aspirations of M. de Rosny, we take him for a spiritual man and, at the same time, for a man of intelligence (which is not synonymous and is instead even better), and we are certain that he does not think about pontificating. But we are equally sure that he is absolutely and irrevocably convinced that eclectic Buddhism is the highest degree to which human conception has risen and can ever rise. Also, we should not be surprised, if we have made his acquaintance, to hear him, the next moment, ask, about Çâka-mouni, the famous question of La Fontaine, about the Prophet Baruch: "Have you read Çâka-muni? He was a fine genius.” (Bourgoint-Lagrange, 1899, p. 2-3).

These years were full of contradiction for Léon de Rosny: the period when the figure of Rosny emerged not only in scholarly circles but also in the public sphere is also when his candidacy for the Collège de France failed against that of Edouard Chavannes (1865-1918). Some see this as the reason for his gradual withdrawal from the academic world, which would guide his choices in dispersing his collection.

The Collection

Although at least two photographs show Léon de Rosny in his office in the rue Duquesne surrounded by his library and Asian objects (a Japanese bell, which we know was offered to him by subscription on the occasion of the first international congress of Orientalists in 1873 [Fabre-Muller B. et al., 2014, p. 118], Tibetan prayer wheels, an Indian statuette, Chinese calligraphy hung on the walls, a Chinese painted scroll unrolled, the Japanese statue of a seated Amida Buddha about 30 cm high, the smaller version of a possibly Burmese or Thai Buddha, a Tibetan-type oblong manuscript and several possibly Chinese scrolls), it does not seem that these or any other collection of works of art have passed on to posterity. Actually, despite the staging of this small cabinet of Asian curiosities, Rosny castigated his contemporaries’ mania for Chinese and Japanese trinkets and, not without malice, in an article explicitly targeting Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), reduced the vogue of Japonisme to an accumulation of "japoniaiseries" (Rosny L., 1901a; Belouad C., 2011, p. 31-32). He thus seems to have been insensitive to the question of an aesthetic renewal in contact with the arts from Asia, unlike for example his pupil and disciple Jacques Tasset (1868-1945).

On the other hand, the trajectory of Rosny bore witness, if not to his bibliomania, at least to his refined taste for bibliophilia and in particular to the place of the Japanese book at the time of Japonisme and its influence on Orientalism in France (Marquet C., 2021). His libraries of Asian works and Orientalist studies in European languages have been preserved in various places with remarkable integrity. Let us thus point out the first gift made by Rosny to the library of the Sorbonne (BIS) in 1902. The books included in the gift (listed RLPX), 100 in "Tartar and Manchurian" languages, bear the stamp "Collection Henry de Rosny" (1873 -1894), in memory of the son of Léon de Rosny, who died prematurely and had engaged in Mongolian studies (then called "Tartars and Manchus"). The works in this collection are still only very partially indicated in the computerised catalog of the BIS (communication by Isabelle Diry, curator of the department of manuscripts and old books, BIS). Particularly notable are the two manuscripts marked MS 1560-1561, "Wen Siouen" (Wen zi), 18th century translations into Manchu from Tong Xiao's anthology of Chinese literature (0501-0531).

Léon de Rosny subsequently abandoned bequeathing the rest of his library to the Sorbonne, with which he had fallen out, preferring to decentralise his collection to the provinces (Delrue-Vandenbulcken L., 2014, p. 303) by donating his collection of works in Chinese (around 500 titles, partly inherited from his master Stanislas Julien [1797-1873], Sun L., 2004) and Japanese (around 400 titles, Kornicki P., 1994), supplemented by a few maps (in particular JAP-97) and prints (notably by Nishikawa Ryûshôdô, JAP-94), to the city of Lille from 1906, then in 1911 and in 1913 (Marquet C., 2022, p. 389; Delrue-Vandenbulcke L., 2014 ). In the Chinese collection, we can note a collection of operas from the Yuan period published in 1573 (CHI-295), an edition of the Lotus Sūtra from 1496 (CHI-65) and a World Atlas from 1849 (CHI-241). The Japanese collection reveals the early acquisition of books by Rosny (the first, an edition of the Heike monogatari published between 1710 and 1750, bears the handwritten ex-libris dated 1854). Among the works on a wide variety of literary and scientific subjects collected by Rosny, the oldest is a princeps edition (1644) of the “Chronicle of ancient facts" Kojiki (JAP-228). The whole is now kept at the Bibliothèque municipale de Lille. Along with the Asian library of Émile Guimet (1836-1918), the learned Sino-Japanese library of Rosny is an exception, as it is the only one preserved in its original state in France (Marquet C., 2022, p. 390). Some other of his Japanese books, marked with his stamp (Roni-in 羅尼印), donated to the École des langues orientales (Marquet C., 2017, p. 33-34), including works purchased from the Orthodox priest Makhov (communication by Benjamin Guichard, director of research and curator of BULAC), are now kept at the Bibliothèque universitaire de langues des langues et civilisations (BULAC) and are registered under the numbers ARC.BLO.12, ARC.BLO.18, and ARC.BLO.19. It should be noted in this respect that Rosny contributed, while he was teaching at the École des langues orientales, to the constitution of the Japanese collection of the library through proposals for acquisitions. However, it was a work transmitted during his lifetime. The works disseminated in other libraries are rarer, such as that of the Missions étrangères de Paris, the National Central Library in Rome (in the Carlo Valenziani collection), or the Bibliotheca Lindesiana of John Rylands University in Manchester, in the part of the 1901 acquisition of the library of Alexander Lindsay (1812-1880), 25th Earl of Crawford (Kornicki P., 1993).

Finally, we must underscore the richness of the orientalist library in Western languages of Léon de Rosny kept at the Bibliothèque municipale de Lille (Fonds Léon de Rosny, 2008, call numbers RU4-017.1-ROS and SU4-017.1-ROS, and Fonds régional), a collection which also preserves the author's works and reprints, the volumes of journals of the various learned societies he founded, as well as a remarkable collection of press clippings in twelve volumes, entitled “Le Bouddhisme en Europe” and subtitled "Documents pour l’histoire de l’introduction du bouddhisme en Europe" (ROS-210). Rosny collected the very numerous paragraphs and interviews which were devoted to him between the years 1890 and 1893, i.e. the years of "eclectic Buddhism", to which he added clippings in multiple European languages of articles relating to the manifestations of Buddhism in Europe.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne