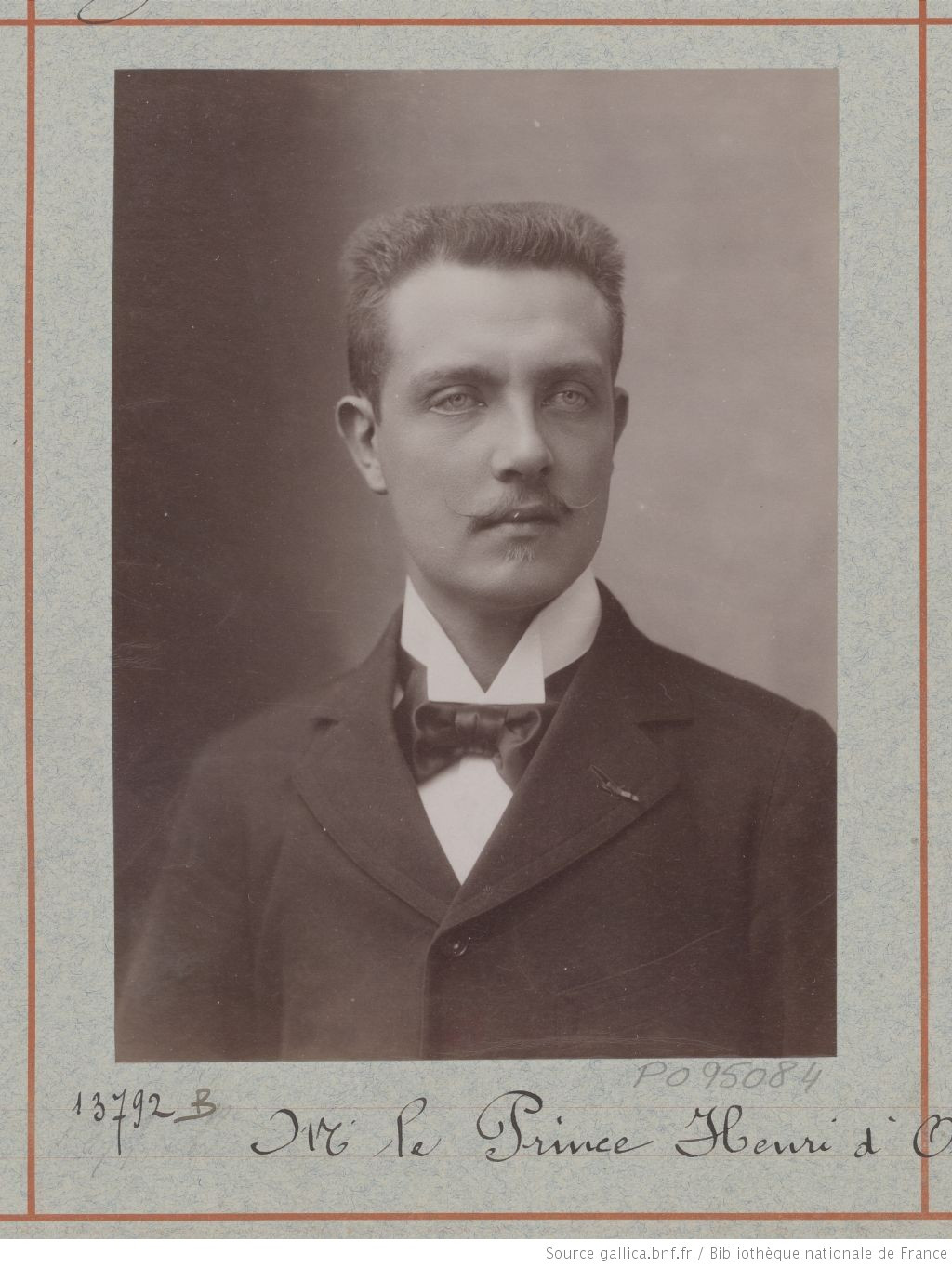

ORLÉANS Henri d' (EN)

Biographical Article

Henri Philippe Marie d'Orléans was born on October 16, 1867 at Morgan House, in the town of Ham (England). He was the son of Robert d'Orléans, Duc de Chartres (1840-1910), and his wife and first cousin Françoise d'Orléans (1844-1925), both descendants of King Louis-Philippe. His life has been well documented by biographers (Dufeuille E., 1902, Belaigues B., 2016). He was a photographer, painter, writer, explorer, and naturalist. In 1886, he fell subject to the law of exile, which prohibited the national territory to the heads of houses that had once reigned over France and also excluded the princes of these families from the army. His name was thus removed from the lists of Saint-Cyr, where he had just been accepted.

In 1889, he left with Gabriel Bonvalot (1853-1933) for an exploration trip financed by his father. Gabriel Bonvalot, originally from Champagne, had settled in Paris after the war of 1870 and then visited central Europe on foot. In 1880, the Ministry of Public Instruction entrusted him with an archaeological mission to Russian Turkestan where he was joined by the naturalist Guillaume Capus (1857-1931) (Bonvalot G., 1884 and 1885). The ministry then entrusted him with his first voyage of exploration proper, with Capus and the painter Albert Pépin (1849-1917), "from the Caucasus to India through the Pamirs" (Bonvalot G., 1889). Held prisoners by the Afghans of Kafiristan, they owed their release only to the intervention of the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin. On his return in 1887, Bonvalot received the gold medal from the Société de géographie de Paris and the Légion d’honneur. After having visited the Exposition universelle held in Paris in 1889, noting the remarkable absence of Tibet in the pavilions and display cases scattered between the Champ-de-Mars, the Trocadéro, and the Esplanade des Invalides, Bonvalot conceived the project of crossing Tibet, which could be described as a "geographico-cynegetic expedition" (Broc N., 1992, p. 43-48). After his many explorations, Bonvalot continued to frequent the world of explorers. He also founded the Dupleix Committee following a trip to Algeria and engaged in the defence of colonialism; he then joined the nationalist party, and was elected deputy for Paris in 1902. Bonvalot's political activities resulted in his being flagged by the intelligence agencies (AN, 19940434/464). His works subsequent to his travelogues testify to his ideological struggles (Bonvalot G., 1897b, 1899b, 1902, 1911, 1913).

Subsidised by the Duke of Chartres, Bonvalot's mission in Tibet doubled as a mentoring role, the urbane mores of the young prince, whose gallantry the press did not hesitate to display, being an explicit cause of this distant trip, as the letters sent to him by his father and mother clearly express (AN, AP/300(III)/233-235). For his part, the prince justified his departure for the austere deserts of Central Asia and Tibet on other grounds: "When my father asked me if I wanted to leave for Central Asia with Mr. Bonvalot, I had no hesitation; I have always had a sort of filial love for the old continent; it seems to me that he has a right to a veneration, a respect, which neither Africa nor America can claim. […] The unknown exerted an additional attraction on my imagination” (Orléans H., 1891, p. 482). Prince Henri and Bonvalot left in July 1889 and passed through Moscow, crossed the Urals and reached Chinese Turkestan, where they were joined by Father Constant de Deken (1852-1896) and a guide, Rachmed, who had previously served the Russian explorer Nikolai Prjevalski (1839-1888). They crossed the Tien Shan Mountains and the Tarim Desert and passed through Lob Nor. Then they reached the Tibetan plateau through the Altyn Tagh mountains. The travellers, in unknown territory, generously sprinkled the map with French names. For a month, the solitude was complete. The first Tibetans, nomadic pastoralists, were encountered on January 31, 1890 near Lake Tengri Nor. The travellers then joined the road from Xining to Lhasa, but could reach the capital. They then headed east and reached Batang in Kham, where they found French missionaries. They crossed Litang and Tatsienlou (Kangding) before heading in the direction of Hanoi. While the travellers covered remarkable distances on foot (including 3,000 in unknown terrain on the Tibetan plateau), their mission brought back relatively disappointing scientific results. As a unique case in history, however, Bonvalot was awarded the gold medal of the Société de géographie de Paris for a second time in 1891 (Baud A., 2003, p. 64).

Through the three travellers’ feats, Tibet made headlines; this event can be seen as the birth of a “French culture of exploring Tibet” (Thévoz S., 2010). Having become the media icons of the exploration of Asia, Henri d'Orléans and his two traveling companions were solicited for many public lectures or by learned societies in France, Belgium, and Switzerland. At the request of the Revue des deux-mondes, Henri d'Orléans published a short account of the trip (Orléans H., 1891a), although he kept his travel journey in his logbooks (AN, AP/300 (III)/257/B), and also wrote his story, which remained in manuscript form. Writing the story of the trip in serial form in the press and then in book form, however, fell to the expeditions’ leader, Gabriel Bonvalot (Bonvalot G., 1892, 1895, 1897a, 1899a) and Constant de Deken, who published his own account in Belgium (De Deken, C., 1894) — not without attracting the strong animosity of Bonvalot, which Henri d'Orléans managed to temper, as evidenced by an exchange of letters (AN, AP /300(III)/236-238). Henri d'Orléans, for his part, published works relating to the explorers and missionaries of Tibet, defending in particular his sole French predecessor in Tibet, the famous father Régis-Evariste Huc (1813-1860) (Orléans H., 1891b, 1893). Bonvalot's letters to Henri d'Orléans also tell us that the travellers had returned to France accompanied by their guide Rachmed (AN, AP/300(III)/236). Rachmed who was an important figure in Bonvalot's published accounts, even became a central literary figure in episodes inspired by their journey in Les Cinq sous de Lavarède, one of Paul d'Ivoi and Henri Chabrillat's best-selling Voyages excentriques (1894). This is only one of the many reappearances of travellers and their stories in popular literature and in adventure novels, in the tradition of Jules Verne who evoked Bonvalot and Henri d'Orléans in 1892 in Claudius Bombarnac up through the recent fictional story Race to Tibet (Schiller S., 2015).

In 1894, after a solo trip to Southeast Asia during which, at the encouragement of Bonvalot (AN, AP/300(III)/236-238), he moved away from his rediscovered Parisian habits, Henri d’Orléans organised a new expedition to the borders of Tibet, which would earn him the gold medal of the Société de géographie de Paris. Accompanied from Hanoi by Pierre Briffaut (or Briffaud, 18...-19...), established in Indochina, engaged as an interpreter, and Émile Roux (1863-1951), naval officer, as a geographer, Henri d' Orléans extended his 1892 journey north (Orléans H., 1894) and reached Tali-fou (Dali) in Yunnan, from where the men recognised the upper courses of the Mekong and the Salween (Orléans H., 1898, Roux E., 1897). Entering the navy in 1891, Émile Roux landed in India the following year, actualising his dream of penetrating the heart of the Asian continent by joining the project of the Prince d’Orléans. It was during a solo excursion that Roux went to Atentze, in Tibetan land, and saw the peaks of Dokerla (Kawakarpo). It was also he who unravelled the enigma of the sources of the Irawady, by refuting the idea of a distant source in Tibet. The mission reached Calcutta on January 6, 1896, after which Roux returned to the navy as an ensign. In the wake of his trip with Henri d'Orléans, Émile Roux submitted a request to the Ministry of Public Instruction for a mission to explore Tibet, which was accepted against those of Charles-Eude Bonin (1865-1929) and Fernand Grenard (1866-1945); as Roux could not carry out his project for family reasons, his proposal was referred to Bonin (AN, F/17/3004/2).Back in France, having been named chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur on March 14, 1896, Henri d'Orléans confided an idea to Henri Cordier (1849-1925) who was a sinologist, professor at the École des langues orientales and editor-in-chief of the magazine T'oung Pao. This idea, supported by his friend Pierre Lefèvre-Pontalis (1864-1938), diplomat and explorer of Laos, was to create the group of “French Asians”; it would achieve lasting success and prove a useful indicator of the social dynamics of travelling in Asia among the French. Proposed in a letter of April 25, 1896 to bring together French people who had traveled or stayed in Asia and to offer them the possibility of discussing political, commercial, colonial, or scientific questions, the project was swiftly concretised by regular dinners and lunches, sometimes including lectures by personalities returning from Asia. These "Asian meetings", in which Henri Cordier was frequently in the company not only of Henri d'Orléans and his traveling companions, but also many figures of Asian studies and the exploration such as Édouard Chavannes (1865-1918), Henri d'Ollone (1868-1945), Pierre Gabriel Edmond Grellet des Prades de Fleurelle (1873-19…), Jacques Bacot (1877-1965) or Aimé-François Legendre (1867-1951), took place regularly in Paris, also after the death of Henri d'Orléans, probably until 1914 (BIF Ms 5445, Ms 5472, Ms 5477).

As the list of the prince's travels shows, the taste for exploration also led him to the African continent several times, in particular to Ethiopia in 1897, where Bonvalot also happened to be, resulting in some friction between them, noted by the press (AN, AP/300(III)/238). His final trip brought the prince back in 1901 to "our mother to all, old Asia" (Orléans H., 1891a, p. 481) for a voyage of exploration of the border regions of Cochinchina and Annam. In June, he suffered from what his companions thought was an attack of malaria and was repatriated to Saigon hospital in July, where he died of intestinal ulceration on August 9, 1901. In a text entitled L’Âme du voyageur, published posthumously by his secretary François Eugène Dufeuille (1842-1911), the prince shared his “art as viaticum”, the quintessence of his life spent travelling: "Explorers must resign themselves to fatigue, to sufferings, sometimes to illnesses, constantly to misery. The job is tough, and we feel sorry for them. For me, I pity those who have not travelled. I am not a psychologist, but I tried to analyse the state of mind of the traveller. I wanted to know his "private room"; for this I looked deep within myself; from my ideas and my feelings, I have tried to extract that je ne sais quoi that makes those who have tasted it adore the wandering life. Here is what I found: besides the satisfaction of duty accomplished or services rendered to science and to the fatherland, besides the enjoyments of a free and active life, one of the charms of travel lies in the work of comparison, which someone who is used to looking constantly and effortlessly does. By virtue of seeing men of different races under various climates and in various conditions of existence, we discover points common to all; through this observation, one gradually forms an opinion on the general questions which most preoccupy humanity. […] In his eyes appears the fatal order of the stages of civilisation. […] He even believes he can go further and penetrate to the depths of souls. […] The traveller does not only reap the benefit of conscious work; he experiences sensations known only to himself, deep, clear sensations, which leave an impression on him forever as vivid as on the first day. […] In these moments of revelation, the traveler who sketches in his notebook does not feel himself writing; his hand seems to run by itself, pushed by an unknown force, and the mood is reflected in these pages as in a mirror.”

The Collection

While the preeminence of the written accounts of the Tibetan journey went to the explorer Gabriel Bonvalot, the collections brought back to France remain associated with the name of Prince Henri d'Orléans. Passionate about botany and natural history, Prince Henri d'Orléans gathered considerable collections during his travels for the Muséum rue Cuvier and maintained a regular correspondence with Alphonse Milne-Edwards (1835-1900), its director, himself author of several studies on the fauna of Central Asia and Tibet. Many specimens, collected in particular during the trip to Tibet in 1890, bear the prince’s name.

Among the objects of Asian art, let us first mention the collection of manuscripts collected during the 1895 trip, given to Henri Cordier (BIF, Ms 5472) and registered in the library of the École des langues orientales on April 1, 1896. This consisted of seven lü (lué or paï) manuscripts and 17 Yi (lolo) manuscripts, partially purchased in Chengdu, most of them in the form of scrolls and, a rare occurrence, enriched with illustrations. An earlier donation dating back to March 9, 1893 (1892 trip) of Thai manuscripts from Luang Prabang, Yao, Lolo, and Muong (Cordier H., 1894) could not yet be located in the collections assembled at BULAC.

The Musée Guimet, with whose curator Léon-Joseph de Milloué (1842-192…) the Prince of Orléans was in contact as soon as he returned from Tibet (BIF, Ms 5472), preserves for its part about 60 listed objects according to four entries: MG 5801-5806 (on deposit at the Musée Georges Labit in Toulouse), MG 10727-10728 (acquired in 1894), MG11001-11043 (acquired in November 1891), and MG 11337-11346 (undated , probably following the trip of 1892). Some of the pieces from the last three entries are on deposit at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Nantes and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes. Coming from the different regions of Asia visited by the prince, these objects are all small in size, with the exception of a few medium-sized Thai statuettes. There are mainly statuettes and a few Buddhist objects of worship in embossed metal, wood or terracotta (mainly Tibetan and Thai, to a lesser extent Vietnamese and Lao), as well as a rich collection of polychrome enamel bowls and pots with lids from Thailand.

In addition, as part of the donation from the Musée Guimet of part of his ethnographic collection of Asia in December 1900, including objects from the Notovitch, Bonin, Ujfalvy collections, etc., a series of objects brought back from Tibet, Malaysia and Laos by Henri d'Orléans are preserved in the ethnographic museum of the Université de Bordeaux, which then depended on the Faculty of Medicine (Vivez J., 1977, p. 1-21). The objects had not been catalogued and only a few had labels with indications. If the current catalogue counts about twenty objects, mainly in wood, vegetable fibres, and bamboo, used for hunting, the handwritten list drawn up in 1901 lists a few hundred objects (files from nos. 282 to 376), which mainly include everyday objects, objects of worship, and clothing (MEB, Orleans inventory B4-154).

The Archives nationales, in the collection of the Maison de France, keep some 30 old and handwritten maps (AN, CP/AP/300(III)/350), as well as a rich collection of photographic plates produced by the prince during his many travels and used for the engravings illustrating both his own stories and those of his traveling companions (AN, AP/300(III)/258-313).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne