MAINDRON Maurice (EN)

Biographical Article

Maurice Maindron was a French writer, naturalist, explorer and archaeologist. He was the son of the famous statuary sculptor Étienne Hippolyte Maindron (1801-1884) and Elvire Biwer (c. 1831-1906). Although born in Paris, he was baptized in Bourges at the parish of Notre-Dame de Château-Roux on October 8, 1857 (BA, Ms-14352/1). An only son, Maurice Maindron went to college and then to the Lycée Saint-Louis in Paris. From an early age he was drawn to both classics and science, which led him to obtain the baccalauréat in both science and literature (philosophy) in 1875. He then turned to medical studies (1875-1876), which were interrupted by the draft for military recruitment (he was exempted due to myopia) (AD75, DR1_0405). Following his exemption, rather than continuing his medical studies, he enlisted in the Navy and embarked as an associate on the Raffray mission.

Maindron had a taste for travel and despite facing a number of administrative pitfalls, he departed to explore many countries until 1901 as part of unpaid missions: New Guinea (1876-1877), Senegal (1879), India (1880-1881), Indonesia (1884-1885), Djibouti (1893-1894), the Gulf of Oman, India (1896), and again India (1901). These trips shaped the character of the young Maindron, and with both his literary and the scientific sides he drew from these discoveries and memories the material necessary for his research and novels. He was interested in archaeology, particularly weapons, in which he specialised. He was appointed Officier of the Académie in 1888 and Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Légion d’honneur in 1900 (LH/1696/11), but never managed to enter the Institut.

Before his marriage, Maurice Maindron lived quite modestly and worked as a preparator at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in various laboratories (in particular, entomology and herpetology), then as a preparator for manual work at the École normale supérieure. Through his marriage in 1899 to Hélène Caradic de Heredia (1871-1953), he became the son-in-law of the famous Parnassian poet, José-Maria de Heredia, who would help him in his career as a novelist. He moved into the Heredia home and thereafter gained greater material comfort. He reconciled the natural sciences and historical literature, his two great passions, until the end of his life. He died on July 19, 1911 and was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery with the Heredia family; under his name, the maxim In umbra alarum tuorum sperabo is engraved.

Entomologist and Zoologist

Entomology, a childhood passion, was an important field in which Maindron distinguished himself brilliantly. He first devoted himself to hymenopteras, especially vespiforms, in the years 1870-1880, bringing back from his travels an impressive collection of wasp nests with their inhabitants. He described several new species in 1878, the year he joined the Société entomologique de France, which he chaired in 1910. He studied the Sphecidae, Chalcididae and Eumenidae families most closely. From the 1890s, carabid beetles and tiger beetles occupied his leisure time; he described many new species during his travels, particularly in New Guinea and India, and assembled an important reference collection which he left to the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. His discoveries were the subject of articles or memoirs by various entomologists, such as Maurice Pic (1866-1957), Maurice Régimbert (1852-1907), and Albert Fauvel (1851-1909).

He has been described as a misanthrope, but that did not prevent him from being in close contact with many well-known entomologists, including, in addition to those previously mentioned, Charles Alluaud (1861-1949), René Oberthür (1852-1944), Edmond Fleutiaux (1858-1931), and Raffaello Gestro (1845-1936). As proof of the recognition of his peers, several dozen species bear his name, maindroni. His colleagues and friends provided him with specimens for his studies, and he passed along others from groups he did not study; he was a networker and a scholar interested in nomenclature, synonymy, bibliography, and history.

Apart from insects, he was interested in general zoology: birds, mammals, reptiles, echinoderms, worms, crustaceans, etc. The experience of his travels gave him a great general knowledge in zoology. He was interested in the particularities of species, curious adaptations, and biology and wrote numerous popular articles. He joined the Société zoologique de France in 1882.

His erudition and his vast knowledge, added to the meticulousness and rigour required by entomological studies, were all assets for his patient and laborious professional activities: Maindron prepared or corrected manuscripts and wrote thousands of dictionary entries; he wrote all the natural history articles (5,000) for the second supplement to the Grand Dictionnaire du XIXth siècle. For the Dictionnaire des dictionnaires, he wrote 20,000 (Bona D., 1989). He also wrote 17 illustrated popular science articles for the journal La Nature, in the field of natural sciences and ethnology, as well as several books, including Les Papillons, illustrated by Armand-Lucien Clément (1848-1920) with whom he used to work. Maindron was a passionate populariser with a universalist soul.

The Writer

His various activities (preparing manuscripts, writing dictionary articles) were, however, not very profitable: he worked a great deal for little money. His stepfather, José-Maria de Heredia, provided him with substantial help and encouraged him to rise socially. Since his marriage, he frequented a world of writers, poets, and playwrights; it would be in literature that Maindron became most known: Le Tournoi de Vauplassans (1895) received laureates from the Académie. Saint-Cendre (1899), Blancador l'Avantageux (1901), Monsieur de Clérambon (1904), and Le Meilleur Parti (1905) were considered successes, in the genre of the historical novel for the first three, and of theatre for the last. He also published a collection of stories under the name Le Quiver (1907c). These works first appeared in instalments or serialised in journals such as the Revue de Paris before being published in book form, sometimes with illustrations.

Maindron was passionate about the Renaissance (especially the 16th century). He described French customs in great detail during the wars of religion. His rawness was not always appreciated and was sometimes censored (Bona D., 1989). The reception was mixed: if his works satisfied a wide audience, some detractors deemed the 16th century at the time of Louis XIII to be dull (letter from his publisher, Louis Ganderax (1855-1940), (BA, Ms -14352/11) while others were scandalised by and disapproved of the text, such as Augustine, known as Toche Bulteau (1860-1922), a friend of the family, who found it deplorable and unwholesome (BA, Ms-14352/22).

Maindron did not limit himself to the study of the 16th century as is often thought, but also wrote about more recent times: his project was to cover the entire period from the 16th century to the French Revolution through his novels (BA, Ms-14367/52).

His writings are imbued with his archaeological knowledge and his memories from travel, and, conversely, some of his scientific studies are inspired by romantic literature. His pamphletary work L'Arbre de Science, published in 1906, clearly shows his dual interest in literature and science, satirising the scientific world at the museum based on his personal experiences (alias Médéric Bonnereau in the novel), poking fun at the professors, of whom he painted scornful portraits: "You can make a professor of natural history, but a naturalist makes himself" (Maindron M., 1906, p. 14; see also Jaussaud P. and Brygoo E.-R., 2004, pp. 26-27). All were ferociously caricatured, starting with Edmond Perrier alias Mirifisc, described as a "wound of the sick tree", attracting enmity against the author and probably costing him his entrance to the Académie française (Loison L., 2008). This resentful settling of accounts also reflects his failure to become more fully integrated into the museum.

His literary oeuvre took its cue from Prosper Mérimée (1803-1870), whom he nonetheless criticised harshly (Maindron M., 1909; see also Mombert S., 1997, 2010), and Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), whom he appreciated; it oscillates between romanticism and realism. However, his works are rather novels of manners than historical novels strictly speaking: it is the study of French society that primarily interested him.

Flaubert’s Salammbô aroused a taste for exoticism in many authors, who sought to imitate him. Maindron distinguished himself from his contemporaries by describing objects with "the meticulous care of an antiquarian", to such an extent that his historical descriptions, in Le Tournoi de Vauplassans, "are akin to the bric-a-brac of the trinket aesthetic that Indian Art, for example, will reveal” (Saliceto E. and Delias G., 2008). To Flaubertian realism, Maindron added unparalleled scientific and terminological precision. The exoticism of the words used by Flaubert in his descriptions, which participate in transporting the reader to a distant reality (Marcil D., 2006), is present in exaggerated form in the work of Maindron. But unlike Flaubert, he demonstrated great accuracy in the use of words. This exotic language, however, was sometimes perceived as a little too precious.

In addition to the novel and the theatre, he also seems to have formulated a project, in 1907, to write a Histoire des Guerres de religion (BA, Ms-14580/2).

Archaeologist and Art Lover

Educated about art at a very young age in his father's workshop, Maurice Maindron practiced his eye and developed a taste for shapes and colours that he used in his missions and his research on weapons, costumes, and later, Indian art (Doumic R., 1911, p. 6).

On his first mission to New Guinea, in 1876, he collected ethnographic objects in addition to natural science collections (Peltier P., 2016); he took notes, made sketches (Bib. Arsenal, Ms-14571), and published a text on "the races of men of New Guinea" (Maindron M., 1881).

Between 1889 and 1894, he devoted 21 articles (Maindron M., 1895, p. 17) to weapons, before publishing a scholarly study on the subject (Les Armes, 1890), followed by a directory of the marks of the most celebrated gunsmiths in Europe between the 15th and 17th centuries. Richly illustrated, this work, which describes armour and swords, covers the periods from the Stone Age until the 18th century, and promotes the Renaissance, the peak of the ornamental art of armament before its "decadence" due to the appearance, among other things, of firearms (Mombert S., 2008). He acquired undisputed authority on this subject (Curinier, 1899-1919, p. X). He also published a series of articles on medieval archeology in the Nouveau Larousse illustré as well as a Dictionnaire du costume du Moyen Âge au XIXe siècle (1907b). He was a founding member and vice-president of the Société de l’Histoire du costume in Paris, and this work anticipated plans for a Musée du Costume (Lottery F., Al-Matary S., 2008).

Becoming a member of the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris in 1892, he continued his collections in 1894 in Djibouti, and in 1896 during a scientific mission in the Persian Gulf and India.

Two years later, he devoted a rich work to Art indien (1898). He then took care to contact the Musée Guimet, to ask for advice on his work (AMG, s.c.). Illustrated with engraved plates, including a series of works from the Musée Guimet, this work was designed as a vade-mecum for creating an Indian museum in Paris (Maindron M., 1898, p. IX). Divided into twelve chapters, half of the book is devoted to the classical arts - architecture, sculpture, painting - while the other focuses on the decorative arts and is partly illustrated by the author's collections. Rich in references to the Indianists who preceded him, this work remains veryimbued with Maurice Maindron's continuous nostalgia for ancient times. Thus, for him, "the history of Indian sculpture is only the history of decadence, (and) this reproach can be addressed, in all fairness, to painting" (Maindron M., 1898, p. 147). Pushing a little further, his positive opinion about the decorative arts, which “best show this intimacy and this preciousness in the rendering, this fundamental elegance which make Indian art so beloved and lend it one of the best places among those of the 'extreme Orient’” (Maindron M., 1898, p. 195), applies only to works that had not undergone external influences, namely 'modern' imports that pollute the original art. The other pitfall of the book is the critical and derogatory gaze cast on local populations "which is based both on a conception that could be described as racist of the superiority of whites over other peoples and on the certainty that colonial policy must be tough […]” (Mombert S., 2008). However, this position must be qualified, and must be placed in a historical context where the racial question was at the heart of anthropological studies.

Years later, on his return from his last mission to India in 1901, he confirmed that "the singular love that [he] bore to times past was perhaps too exclusive to inspire [him], vis-à-vis the present, to a feeling other than an indifferent fairness” (Maindron M., 1907a, p. VI.)

However, it would have taken a lot of effort to be able to carry out this mission of study and collection complementing the two previous ones. Regarding his knowledge of the Malay languages and the Mafor Island dialect [Numfoor] pleads in his favour (AN, F/17/2986/2). After many letters between Maindron, the ministries, and the shipping company, he obtained, in 1901, the agreement of the state, the financing, and the recommendations necessary to carry out his mission in India (AN, F/17/2986/2). He left in February-March 1901, stayed in Pondicherry from May to August, and then returned to Paris on November 8. The letters and notes written in Pondicherry are published in his book Dans l'Inde du Sud (Maindron M., 1907a, 1909). Very descriptive, this text recounts his journey in detail and provides information on his collection.

At the same time, a family friend was amused by the exotic bric-a-brac in which the Maindrons lived: "It's like being at a rajah, a cacique, or a condottière. On the walls hung with fabrics from India hang bows, javelins, swords, rapiers. There are stuffed birds, butterflies, insects, books, a transparent stone Buddha that looks like frog spawn. In the antechamber, we see a showcase of slippers and two horse saddles with harnesses, and Hélène carries a travel bag in python skin” (Goujon J.-P., 2002, p. 485).

In 1906, he became a member of the Société des Antiquaires de France. He died in 1912. On July 5, his widow contacted the Musée Guimet to donate the collection brought back from his last trip (AMG, s.c.). Émile Guimet, in the midst of a project to reopen a museum in Lyon, had it donated to the city.

The Collection

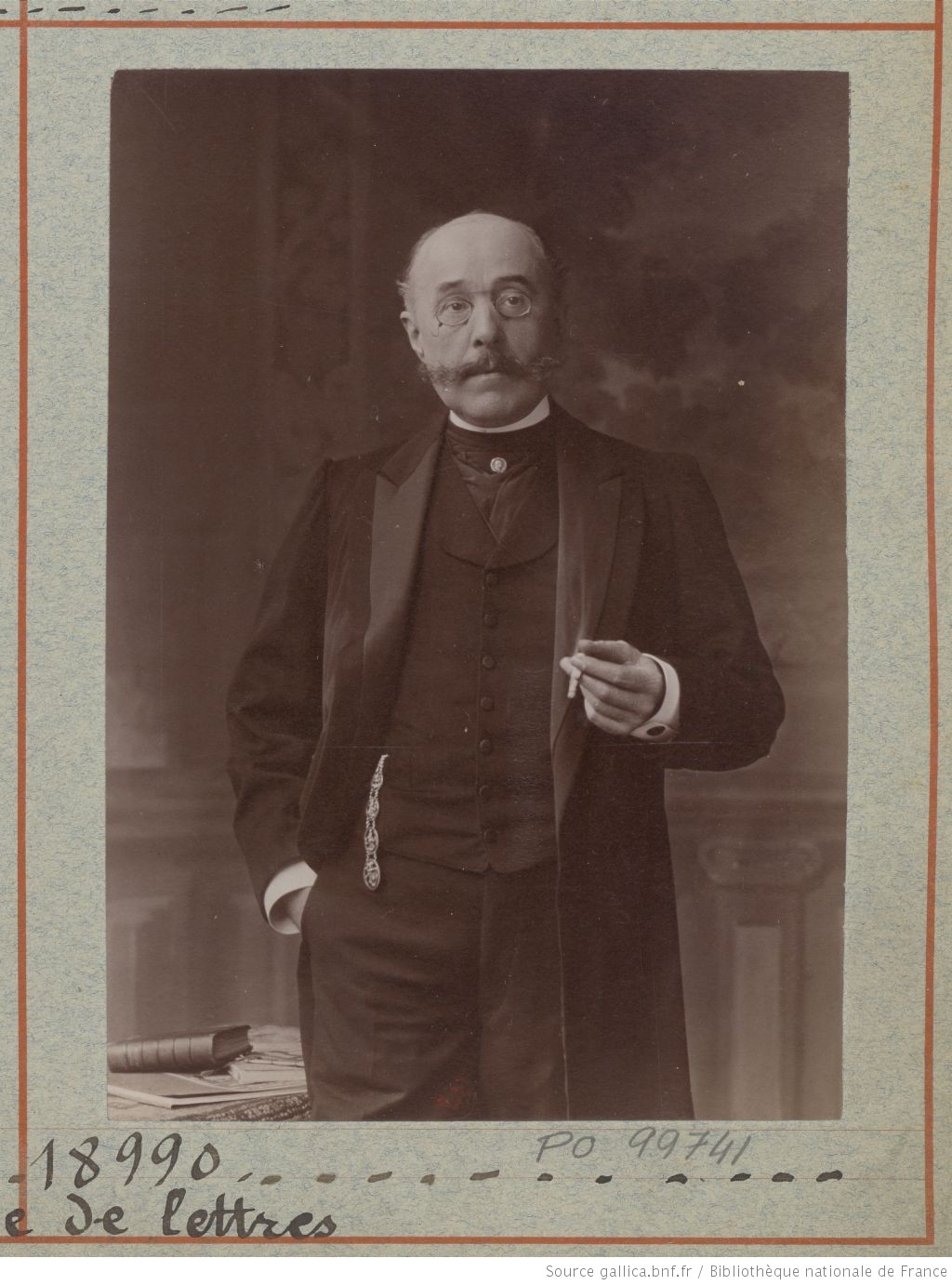

The face of Maurice Maindron is easily known today, as there are many portraits of him. A pastel portrait by Laure Richard-Troncy (1867-1950) is kept at the Musée Carnavalet (inv. D.8144); a series of photographs by Atelier Nadar can be found at the Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine (RMN-GP, inv. no. APNADAR013689, APNADAR013688, APNADAR012341, APNADAR013823); sketches and photographs are in the archives of the bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, etc.

The Natural Science Collections

Regarding natural history, we owe Maindron a beautiful set of specimens of vertebrate and invertebrate animals, brought from his various missions and kept at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (for example, inv. no. MNHN-MY-MY9707, MNHN-RS-RS1841, MNHN-RS-RS0310). Details concerning them are given in his reports, the mission archives (AN, F/17/2986/2), and his booklet presenting his titles and works (Maindron M., 1895).

The entomological collections are the most remarkable (several thousand specimens) and new species are still described today from its material. Among them, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera are the best represented orders of insects. Some of the zoological specimens, in particular invertebrates, are preserved in alcohol, some botanical samples and parts of herbariums have been transferred to the MNHN. It is also necessary to add a collection of beetles which was given to Guy Babault (1888-1930) before joining the MNHN collections.

Ethnographic Collections

From his first exploration mission in New Guinea, Maindron collected ethnographic pieces (Maindron M., 1879). In 1877, he deposited part of it in the Musée de l’Artillerie at the Hôtel des Invalides where they would dress a mannequin of a Papuan warrior. The gallery opened on December 17, 1877 in a "living" setting. These objects were donated to the Trocadéro museum in 1917. The other part of the Maindron collection, 66 objects, arrived at the Musée du Boulogne-sur-Mer in February 1878 through Dr Hamy. 39 are attributed with certainty, among them rare pieces: Korwar funerary statuettes, engraved bamboo lime containers, spatula, paddle and spears engraved with the Korwar motif, a neckrest, four combs, a carved bird, etc. (Boulay R., 1990, p. 34; Joconde database).

In 1880, a new mission led him to India, where he collected a series of skulls of Hindus (in the sense of "Indian", inhabitant of India) collected in Ginji, Pondicherry, and Karikal for the national museum (Lobligeois M., 2001, p. 160) and of which three photographs are kept at the musée du quai Branly. The comparison of the measurements of human skulls was used at the time for the study of races. In the midst of a famine, Maindron obtained skulls from “second-hand gravediggers” with “minor silver coins” (Lobligeois M., 2001, p. 160).

From his mission in Indonesia in 1884-1885, the Quai Branly museum has six glass plates. Several paper prints, negatives and glass plates concern his mission to Obock and Somalia in 1893. But no object in the museum's database seems attributed to Maindron.

On January 11, 1897, in a letter from the Ministry of Public Instruction, Fine Arts and Religion, we learned that Maindron had dispatched 13 parcels from his mission in the Indian Ocean and that these objects were partly intended for national museums (BA, Ms-14561). They consisted of samples of fabrics, carved wood, copper, and enamels which would be published in the Gazette des beaux-arts and given to the Trocadéro museum after study (AN, F/17/2986/2).

From his last trip to India in 1901, Maindron brought back a diverse set of objects including pieces in terracotta (figurines, vases), painted and unpainted wood (figurines), copper and bronze (small religious subjects ), and stone, and finally paintings (on paper, on mica, under glass) as well as various objects and fragments of excavations. His collection was exceptional in terms of the quantity and quality of the works obtained at that time. In addition, his book on the Coromandel provides interesting information about the manufacture and acquisition of parts brought back to France. He mentions the potters Apoupatar, in Cossopaléom, and Vaïtilingam, in Pondicherry, considered as "a master [who] only works on commission" (Maindron M., 1907a, p. 133). He even indicates that "for a small sum, one can compose an ethnographic gallery unlike that of any of our museums" (Maindron M., 1907a, p. 139). His widow finally gave the collection to the city of Lyon for the Musée Guimet in October 1912, including 260 numbers (Arch. Musée des Confluences, 1MGL/8). Some of the pieces may have been acquired during Maindron's first stay in Pondicherry in 1880 or during his mission in 1896, but this remains heretofore impossible to confirm.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne