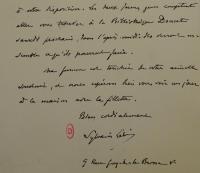

LÉVI Sylvain (EN)

Biographical Article

Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935), professor of "Sanskrit language and literature" at the Collège de France and director of studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE), was one of the greatest Indianists and Orientalists of his time. He was born in Paris on March 28, 1863, into a family from the region of Bas-Rhin. His father, Louis Philippe (1830-1897), was a cloth merchant (AP, ECN/V4E 362/958).

In 1873, Sylvain Lévi entered the sixth grade at the Lycée Charlemagne (Paris IVe) and followed a program of classical studies. In 1881, he passed the baccalaureate, but was refused the entrance examination to the École Normale Supérieure. He studied literature at the Sorbonne and obtained the aggregation in letters in 1883, at the age of 20. The same year, he became a research grantee at section IV of the EPHE, where he took Sanskrit language courses with Abel Bergaigne (1838-1888). He also attended the comparative grammar courses of Michel Bréal (1832-1915) and Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) as well as the lectures on Iranian languages of James Darmesteter (1849-1894) (Bansat-Boudon L., Lardinois R., 2007, p. 31; Lardinois R., 2007, p. 174-175).

In 1886, he was appointed lecturer for the Sanskrit language in the IVth section of the EPHE, and for the religions of India in section V of the EPHE. In 1889, he succeeded Abel Bergaigne, teaching at the Sorbonne as a lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature. He obtained his doctorate in literature in 1890, the main thesis of which was Le Théâtre indien (Lévi S., 1890a) and the secondary thesis Quid de Graecis veterum Indorum monumentatradiderint (Lévi S., 1890b). In 1894, at the age of 31, he was elected professor and chair of "Sanskrit language and literature" at the Collège de France. At the same time, he was elected director of studies for the Sanskrit language and the religions of India at the EPHE (sections IV and V) (Bansat-Boudon L., Lardinois R., 2007, p. 31 Lardinois R., 2007, p. 175-176).

His training and his interest in better understanding the civilisations of Asia, and that of India in particular, make him a scholar with many skills. In the linguistic field, in addition to Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit, he knew Pali, Middle Indian and Iranian languages (Avestic, Pehlevi, Persian), Tocharian, Nepali, Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese, and Uyghur. As well as a philologist and linguist, he was also an epigraphist, numismatist, and historian of countries, religions, and art (Bansat-Boudon L., 2007, p. 21-24). He maintained relations with sinologists such as Édouard Chavannes (1865-1918) and Paul Pelliot (1878-1945), as well as with the anthropologist and sociologist Marcel Mauss (1872-1950) and the Buddhist archaeologist Alfred Foucher (1865- 1952) (Renou L., 1936, p. 13-14; Bongard-Levin G. M., Lardinois R., Vigasin A. A., 2002, p. 38-32; Fournier M., 2007, p. 221-236). Initially interested in Brahmanic and classical India, Sylvain Lévi quickly broadened his field of research to Buddhism, opening his geographical area beyond India. His research thus led him three times on scientific missions to Asia, working as an explorer and decipherer.

The first mission (1897-1898) was carried out under the aegis of the Ministry of Public Instruction and subsidised by the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres for the purposes of linguistic, philosophical and religious studies. He stayed in India, Nepal and Japan, before returning via Russia (Lévi S., 1899a, 1899b). In India, Lévi visited Jain and Buddhist sites and studied Nyāya philosophy in Benares, where he also practiced daily conversations in Sanskrit (Lévi S., 1899a, p. 72). In Nepal, particularly in Kathmandu, where he resided the longest, Lévi studied the religious life of the country through texts, monuments, and practices. He thus collected several manuscripts, mainly Buddhist, original manuscripts on palm leaves, the oldest of which dated from the 11th to the 15th century, or copies made at his request. Lévi also recorded many engraved inscriptions, in order to reconstruct the history of the kingdom of Nepal and provide the scholars of the country with a research program (Lévi S., 1899a, p. 80-85). In Japan, he studied the various schools of Buddhism, stayed in temples, and learned about the literature of Chinese and Japanese commentaries while pursuing his quest for Sanskrit texts. He collected numerous Sino-Japanese works as well as ancient Sanskrit-Chinese dictionaries (Lévi S., 1899a, p. 87-88).

His second mission, from 1921 to 1923, was initially motivated by the invitation of the poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) to teach at the university he had just founded in Shantiniketan (Bengal). While teaching there, Lévi visited Indian archaeological sites (Lévi D., 1925, p. 20-48, 92-96). He stayed for a few months in Nepal, where he resumed his research and study of manuscripts and inscriptions. The rest of the trip took him to Indochina, visiting the site of Angkor for a few days, as well as to Hanoi, and then Japan, where he continued his research in Buddhist libraries and gave lectures at the University of Tokyo (Goloubew V., 1935, pp. 555-557, 561; Lardinois R., Weill G., 2010, pp. 38-39).

His third trip (1926-1928) was mainly focused on Japan where he was appointed director of the Maison franco-japonaise, created in Tokyo in 1924 on the initiative of Viscount Shibusawa Eiichi (1840-1931) and Paul Claudel (1868-1925) (Frank B., 1974). He taught at the university and initiated the Hôbôgirin project, an encyclopaedic dictionary of Buddhism based on Chinese and Japanese sources (Lévi S., Takakusu J., Demiéville P., Gernet J., dir., 1929). In 1928, on his way back, Lévi stopped in Indonesia, at Borobudur where he studied bas-reliefs from the eponymous temple and in Bali where he collected Sanskrit hymns and songs, still recited by the priests of the island. He also made another, final stopover in India and Nepal (Lardinois R, Weill G., 2010, p. 40-42; Lévi S., 1933, p. xiv-xv; Goloubew V., 1935, p. 564 -565; Renou L., 1936, pp. 47-48).

Lévi established close ties in both Asia and Europe, particularly with Russian scholars, including Sergei F. Oldenburg (1863-1934), scholar of Sanskrit and Buddhism and founder of Russian Indianism. Eager to restore the Franco-Russian network of scientific exchanges, interrupted by World War 1 and the Russian Revolution of 1917, he co-founded the Comité français des relations scientifiques avec la Russie in 1925 (Bongard-Levin G. M., Lardinois R., Vigasin A. A., 2002, p. 58-59). He also participated in the founding of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (1898), the Maison franco-japonaise in Tokyo (1924), and the Institut de civilisation indienne in Paris (1927) (Frank B., 1974 Goloubew V., 1935, p. 554; Lardinois R., 2007, p. 117). He was elected president of the Société asiatique de Paris in 1928. In 1934, he was vice-president of the Institut d’études japonaises (La Morandière, 1937, p. 12).

Sylvain Lévi was also involved in the "Jewish cause". As a member of the Jewish Studies Society, he sided with Captain Dreyfus and joined the central committee of the Alliance israélite universelle in 1898, which he represented at the Conférence de la paix de Versailles (1919), then as president from 1920. As a member of the Comité français d’études sionistes, he went on a mission in 1918 to Egypt, Syria and Palestine, then to the United States (Bongard-Levin G. M., Lardinois R., Vigasin A.A., 2002, p. 20). Sylvain Lévi died on October 30, 1935, having fallen ill during a session of the Israelite Alliance in Paris.

Le photographe aurait été identifié comme étant Dirgha Man Citrakar (1877-1951).

The collection put together by Sylvain Lévi reflects a scholar rather than an aesthete, although in his time he contributed to the interpretation of the monuments of Asia, in particular those of Nepal (Lévi S., 1905-1908; Lévi S., November 1925) and Indonesia (Lévi S., 1931).

His collections of manuscripts were originally motivated by the search for the lost originals of Sanskrit literature, sometimes known from Chinese or Tibetan translations of Buddhist texts (Lévi S., 1899a, p. 82).

Sanskrit Manuscripts

With this in mind, he departed on a mission to India and Nepal during the winter of 1897-1898, before continuing to Japan. Nepal was considered a repository for ancient Buddhist manuscripts. Sylvain Lévi was thinking in particular of the outstanding collecting of texts, often unknown in Europe, that had previously been undertaken by Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894) (Lévi S., 1899a, p. 82).

Although initially not very optimistic about his chances of success, the benevolent support of the Nepalese sovereigns finally gave him access to many unpublished Sanskrit texts, in particular Buddhist texts, of which he had copies made. However, he would acquire, or, more often, be offered by the Maharajas or by their rājaguru (royal priest), several authentic ancient manuscripts on palm leaves, whose dates range between the 11th and 15th centuries and which represent very rare versions, even in some cases codices unici. This set of manuscripts includes tantric Buddhist texts (Sarvabuddhasamāyogaḍākinījālaśaṁvara, MS.SL.48), Hindu texts (Śivadharma, MS.SL.57), as well as a synthesis of the Bṛhat-Kathā, or Great History, (Bṛhatkathāślokasaṃgraha, MS.SL.46), a legendary collection of tales which is only known by its quotations or a few collections.

From an artistic viewpoint, however, the most precious manuscript is the one he was given as a diplomatic gift to France, an almost complete manuscript of The Perfection of Wisdom in 8000 Lines (Aṣṭasāhasrikā-Prajñāpāramitā), datable to the 11th century and made in North India, calligraphy in ink on a talipot palm leaf (MS.SL.68). In addition to the text it contains, its interest lies in the delicate paintings on its wooden boards, a rare testimony to the pictorial art of the Indian Pāla dynasty (8th-12th centuries). One of the boards bears the representation of the five transcendental Buddhas and the four Buddhist goddesses associated with wisdom, while the other bears very original illustrations of the past lives of the Buddha, in episodes highlighting the virtue of self-sacrifice.

Nepalese Manuscripts

During his first stay in Nepal, Lévi became interested in the religious and political history of the region and worked to collect documents, manuscripts or copies, field notes and stampings (estampages) of lapidary inscriptions, which would provide the material for his study Le Népal, un royaume hindou, published in three volumes between 1905 and 1908. In this context, he had toponymic lists linked to the legends of the Kathmandu valley copied, such as the Nepālamaṇḍalābhyantarabuddhavihāranāmāni (MS.SL.60). The Mahārāja Deb Shumsher also offered him an exceptional document, the manuscript of the Nepālī Rājāko Vaṃśāvalī (MS.SL.08). This dynastic chronicle of Nepal, linking legendary ancestors and historical sovereigns, is written in Nepali on leperello-bound paper and treated with orpiment. Its frontispiece is illustrated with symbolic representations of emblematic places of the Kingdom (the stūpa of Svayambhunāth, the liṅga of Paśupatinath, a crematorium, the river Vāgmatī) as well as images of the mythical ruler Dharmadatta, the wishing tree and the of Gaṇeśa called Śvetavināyaka (the white [form] of the remover of obstacles). It is one of the central sources of Sylvain Lévi's work on the history of Nepal (Lévi S., 1905, p. 193-201).

From his stay in 1922, Sylvain Lévi became interested in and collected a new type of manuscript: Nepalese manuscripts, also on paper, with leporello bindings, abundantly illustrated in gouache, linked to different Tantric Buddhist rituals. These were relatively recent manuscripts, the oldest dating from 1720 (Manual of the ritual linked to the adamantine maṇḍala or Vajradhātumaṇḍala, MS.SL.59, dated in the colophon of the year 841 of the Nepalese era), the others being copies made at the request of Sylvain Lévi from older manuscripts. The illustrations represent ritual gestures, or mudrā, sometimes with objects (bell, vajra, flowers, etc.) and musical instruments. They guide the ritual which induces the visualisation of certain deities within a maṇḍala.

Although he did not publish these manuscripts, it is highly probable that Sylvain Lévi began researching these specific rituals, as evidenced in his archives by a rather exceptional ethnographic documentation: photos of the mudrā (Collège de France, Service archives, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF, box of photographs "mudras of Nepal: Sylvain Lévi collection"), as well as films documenting these rituals (Collège de France, Service des archives, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF audiovisual archives). The celebrant who agreed to perform these hitherto confidential rites so that they could be documented was Siddhiharṣa Vajrācārya (1879-1952). He had met Lévi during his previous trips and happened to be the copyist of several manuscripts in the collection. It was the Dutch ethnomusicologist Arnold Adriaan Baké (1899-1963) who in 1931 made the photographs and films that today constitute one of the oldest filmed testimonies of Nepal (Baké A. A., 1959, p. 321).

Sylvain Lévi and the Collection of Objects from the Institut d’études indiennes

The name of Sylvain Lévi is also traditionally associated with a collection of objects, mainly Nepalese, kept at the Institut d’études indiennes (formerly the Institut de civilisation indienne) (Mallmann M.-Th., 1964, p. 134-150) of which Lévi was a founder (Lardinois R., 2003-2004, p. 737-748)

In reality, Sylvain Lévi was never the owner of these objects, most of which were gifts to the Institut de civilisation indienne and not to the private person of its vice-president. If the distinction was quite clear during Lévi's lifetime, confusion seems to have set in afterwards in the Indianist community, linking the institute’s collection to its founder. Thus, some of the Nepalese bronzes of the Institut de civilisation indienne (SL.01; SL.02; SL.03; SL.04; SL.05; SL.06; SL.07; SL.08; SL.09; SL.10; SL.11; SL.12; SL.13; SL.14; SL.15; SL.16; SL.17; SL.19; SL.20) were exhibited at the Musée Guimet in 1963 in the Sylvain Lévi Collection, as part of the events linked to the centenary of Lévi’s birth (Mallmann M.-Th. de, 1964).

However, with the exception of the sculpture in lacquered wood of a Japanese bodhisattva (SL.25) whose provenance is not documented and which could have been brought back by Sylvain Lévi from Japan, none of the objects of the Institute have been inherited from the great orientalist.

The heart of the collection, made up of around thirty Nepalese works, was donated to the institute in 1929 by Mahārāja Chandra Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana (1863-Nov. 1929), Prime Minister and Supreme Commander-in-Chief from Nepal. This donation followed an official procedure: Chandra Shumsher, in his capacity as head of government, sent his proposal by mail to the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts in Paris, with the list of objects (Collège de France, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF, correspondence box (envelope XXXV, 5.1).

Lévi did, however, have a link with this collection, but as an intercessor, even initiator, of this gift. He established warm relations with the reigning Nepalese family from his first stay in 1898, which provided him with protection and support in his research, links which he strengthened during his second visit in 1922 (Lévi D., 1926, p. 115-189). He continued to correspond with various members of the dynasty, notably Chandra Shumsher and his son Kaiser (1892-1964), and had photographs and documents sent to him (Collège de France, Service des archives, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF, Box XXXV, Letter from Kaiser Shumsher to Lévi dated December 11, 1924; Box 4, Box B, Letter dated February 15, 1925 from Chandra Shumsher to Sylvain Lévi).

In 1927, Sylvain Lévi created the Institut de civilisation indiennene along with Émile Senart (1847-1928) and Alfred Foucher (1865-1952). He then activated his networks in Europe and Asia for a sponsorship campaign aimed at financing the institute’s activities, publications, and the creation of a library. At his instigation, the Institute would benefit from subsidies from India from the Wadi Trust of Bombay, the Gaekwad of Baroda and the Nizam of Hyderabad (Collège de France, IEI, archives of the Institut d’études indiennes). The Prime Minister of Nepal Chandra Bahadur Shumsher lent his support by donating a collection (Collège de France, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF, correspondence box (envelope XXXV, 5.1). There were no manuscripts this time. Chandra Shumsher had already donated several thousand ancient manuscripts to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 1909 (Pingree D., 1984, p. V), and consequently probably had hardly any left to give to the Institut de civilisation indienne. He therefore offered a collection of objects: bronze sculptures (including a sculpture representing the "Queen Māyā giving birth to the Buddha" SL.16), on wood (scale representation of one of the windows of the Darbar of Patan SL.49), pieces of goldsmithery, lamps, and weapons, highlighting the excellence of Nepalese craftsmen. It seems that it was Chandra Shumsher who himself selected the works constituting this collection. Nevertheless, he was guided in these steps by Sylvain Lévi, and it was on his suggestion that he took up this donation, as he clearly expressed in a letter addressed to the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts. In return, it seems that Chandra Shumsher received various distinctions through Sylvain Lévi’s efforts. The sovereign was decorated as a Grand-Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 1925. This forthcoming distinction was mentioned in 1924 by Kaiser Shumsher in a letter to Sylvain Lévi, in which he thanked him for his intercession (Collège de France, Archives Sylvain Lévi, 41 CDF, box XXXV) and is the subject of an article by Sylvain Lévi in L'Illustration (Lévi S., 1925). In 1929, the year of the donation to the Institut de civilisation indienne, Chandra Shumsher was also elevated to the dignity of Grand-Croix de la Légion d’honneur (Official Directory of the Legion of Honor, Museum of the Legion of Honor).

The Purchase of Sylvain Lévi's Library for the Institut de civilisation indienne

Sylvain Lévi died on October 30, 1935. Alfred Foucher, director of the Institut de civilisation indienne, took steps with the rectorate of Paris to finance the acquisition of his library (AN, 20010498/108).

The section on Sinology was the subject of a summary estimate by Paul Demiéville (1894-1979), that on Indology by Louis Renou (1896-1966) (AN, 20010498/108).

The works of Indology and Sinology, like the manuscripts, would be purchased from the family (the widow of Sylvain Lévi, Désirée (1867-1943) and her two sons, Abel (1890-1942) and Daniel (1892-1967), for the Institut de civilisation indienne by the rectorate of Paris for an amount of 200,000 francs (AN, 20010498/108). The collection moved to the premises of the Institut de civilisation indienne at the Sorbonne in 1936 (AN, 20010498 /108).

The presence of the manuscripts within it is confirmed by a controversy which appears in the archives of the rectorate (AN, 20010498/108: Letter of January 27, 1937, from Julien Cain; Letter of January 30, 1937 from Charles Beaulieux; letter (typescript corrected by hand) of February 1, 1937 from the Office of the Rector of the Université de Paris to M. Foucher; Letter of February 3, 1937 from Alfred Foucher to the rector of the academy): in 1937, Alfred Foucher considered depositing the manuscripts at the Bibliothèque nationale, which earned him a scathing response from the rectorate on the fact that the university was not going to part with the most precious part of a library acquired on its credits.

The collection then followed the peregrinations of the Institut de civilisation indienne (renamed the Institut d’études indiennes in 2001) (Lettre d’information de l’Institut d’études indiennes (Instituts d’Extrême-Orient du Collège de France), No. 11, October 2000, p. 2).

It left the Sorbonne in 1969 for the Maison de l'Asie, 22 avenue du President Wilson Paris 16th (Lettre d’information de l’Institut de civilisation indienne (Instituts d’Extrême-Orient du Collège de France), no. 1, September 1990, p. 2).

In 1973, the Institut d’études indiennes, like the other institutes of Asian Studies under the Université de Paris until then, changed supervision and officially passed into the bosom of the Collège de France (decree 73-47 of January 4 1973). In 1990, it joined the building located at 52 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, which houses the libraries and centres for the study of civilisations of the College de France, now called the Institut des civilisations du Collège de France (Lettre d’information de l’Institut de civilisation indienne (Instituts d’Extrême-Orient du Collège de France), n° 1, September 1990, p. 2).

Some of the manuscripts have been digitised and are published online in the digital library of the Collège de France, Salamandre: https://salamandre.college-de-france.fr

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne