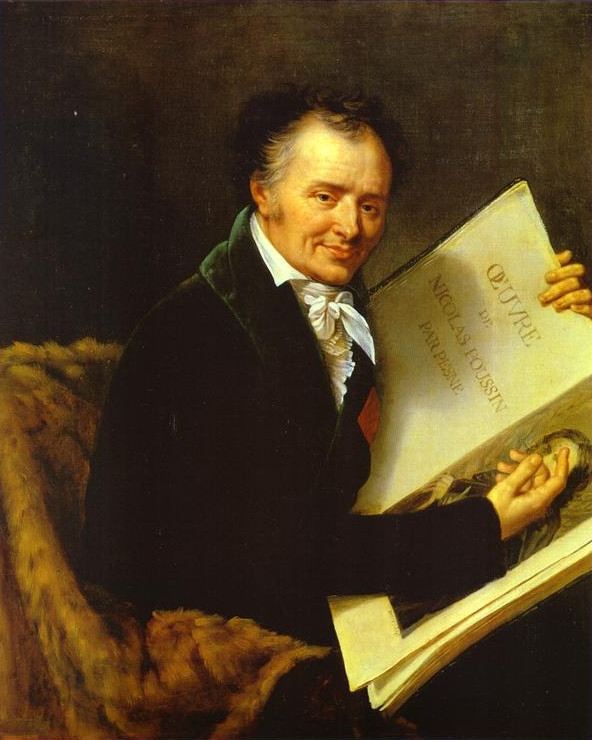

DENON Dominique-Vivant (EN)

Biographical article

Dominique-Vivant Denon was a French diplomat, a literary man, draughtsman, engraver, and collector (see Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey’s article on Dominique-Vivant Denon, ‘Dictionnaire des Historiens de l’Art’, Agorha database, INHA, updated 5 November 2008).

Born in Chalon-sur-Saône on 4 January 1747, he went to Paris in 1764 and began a career as a painter and draughtsman before joining the Court of Louis XV (1710–1774), where he was appointed Gentilhomme Ordinaire de la Chambre du Roi (Ordinary Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber) in 1768 (Lelièvre, P., 1993, p. 16). Then, having become a Gentilhomme d’Ambassade (ambassador gentleman), he made frequent voyages to Russia, Switzerland, and Italy, where he lived from 1778 to 1785, staying in Naples as an Embassy counsellor (Lelièvre, P., 1993, pp. 27–48). He familiarised himself with the collections he visited and the collectors he met. He was particularly interested in antique objects and Greek and Italic vases, considered at the time as ‘Etruscan’, which were much sought after by many connoisseurs on the Grand Tour.

But it was also in this city that he devoted himself to drawing after the masters and engraving, and as soon as he returned to Paris in 1785 he applied to be admitted to the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture. The director of the Bâtiments du Roi, the Comte d’Angiviller (1730–1809), with whom Denon was negotiating for the King’s acquisition of his collection of ‘Etruscan’ vases, accredited him as an ‘artist of various talents’ on 28 July 1787 (Van de Sandt, U., 1999, p. 76). Nevertheless, having abandoned a diplomatic career, he decided to go back to Italy and live there from his art, while familiarising himself with the major local collections. He settled in Venice, where he had a studio at his disposal. His financial resources enabled him to pursue his acquisitions of works of art, mainly drawings and prints, a large number of which he purchased at the sale of Anton Maria Zanetti (1680–1767), a Venetian artist and major connoisseur in the field of engraving. Nevertheless, accused of being a spy of the Convention, he was expelled from Venice in 1793, and returned to France in the midst of the revolutionary upheavals.

As his income had dropped, he moved to Paris, not far from the Louvre, on the Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau (formerly Rue Plâtrière in the 1st arrondissement), on the third floor of the Hôtel Bullion, the famous auction house opened in 1778 by the dealer Alexandre-Joseph Paillet (1743–1814) (Michel, P., 2007, pp. 249–251). Here, it seems very likely that his work as a dealer enabled him to get by, while continuing to acquire objects for his cabinet (Dupuy, M.-A., 1999 or 2016, p. XX). The downfall of Maximilien de Robespierre (1758–1794) in 1794 obliged him to abandon the projects he had committed himself to with the Comité de Salut Public (Van de Sandt, U., 1999, p. 77). During the Directoire he was enlisted as a draughtsman and participated in the Egyptian expedition with Napoléon Bonaparte (1769–1821). He returned with many sketches executed on the spot as well as unique accounts of the ancient pharaonic civilisation, which was only known to a few antique dealers at the time. This led to a vast editorial project, entitled Voyage en la Basse et la Haute-Égypte , which was published in 1802.

The decisive turning point in his career occurred on 19 November 1802. Citizen Denon was appointed Director of the Muséum Central des Arts by the First Consul Bonaparte. He was entrusted not only with the administration of the museum—which was of particular interest to the young Consul—, but also with directing the arts and managing, in addition to the Louvre, the Musée des Monuments Français, the Musée Spécial de l’École Française (The Special Museum of the French School) in the Château of Versailles, the supervision of the Manufactories of Sèvres, Beauvais, and the Gobelins, the government palaces, the Monnaie, the chalcography workshops, architectural works, and the transport of works of art linked to confiscations abroad (Mardrus, F., 2017, pp. 311–312). Denon was fifty-five when he took up this official post, which was coveted by the painter Jacques-Louis David 1748–1825), the sculptor Antonio Canova (1757–1822), and the architect Léon Dufourny (1754–1818). Unfamiliar with the affairs of State administration, he probably had the most suitable profile that matched the authorities’ requirements to implement the artistic polices related to the museum’s development.

The proclamation of the Empire on 18 May 1804 imposed a new hierarchy on the museum, renamed by Denon the Musée Napoléon. It now depended on the imperial civil list, rather than the French Ministry of the Interior, and hence on the Intendant General of the Emperor’s household for its budget. Denon’s directorship was distinguished by one ambition—to turn the Louvre into ‘the finest museum in the world’ (Dupuy, M.-A., 2016, I, pp. 694–704). On the occasion of Napoleon’s marriage with Marie-Louise of Austria (1791–1847) in 1810, the Grande Galerie was refurbished by the architects Pierre-François Fontaine (1762–1853) and Charles Percier (1764–1838) for the exhibition of paintings planned by Denon, who turned this event into a decisive point in establishing the museum’s reputation. He highlighted the history of the art of painting according to Schools, and the artists who belonged to them. For the first time, he provided visitors with an unparalleled collection of masterpieces that came from the royal collection—which had been nationalised during the Revolution—, the works of the émigrés, and the many confiscations made by the French army abroad from 1794 onwards.

From 1805 to 1811, Denon went on many missions to the countries conquered by the Emperor to collect the necessary works for the museum and, as a result, he was nicknamed the ‘huissier–priseur’ (‘auctioneer’) of Europe by one of his many biographers, Jean Chatelain (Chatelain, J., 1999, pp. 161–187). The Napoleonic inventory of the museum’s collections in several volumes (AN (French national archives), 20150162/14-20150162/52) constitutes an exemplary scientific work about this institution between 1804 and 1815. It was even more valuable when the fall of the Empire in 1815 led to the restitution of most of the confiscated works to the nations allied against France. In October 1815, Denon presented his resignation to King Louis XVIII (1755–1824).

Now retired, Denon left his official accommodation in the Louvre and moved to 5, Quai Voltaire (now no. 7) in the apartment he had rented since 1813 on the first floor, opposite the Louvre. During the ten years leading up to his death, on 28 April 1825 (AN (French national archives), MC/RS//249), he devoted himself to presenting his collections in his apartment and their constant enrichment, supported by continual visits from friends and acquaintances who were eager to see his cabinet and listen to what he had to say.

The collection

Dominique-Vivant Denon died on 28 April 1825 in his apartment at 5, Quai Voltaire (today no. 7), surrounded by the objects he had acquired with such passion. The post-death inventory drawn up between 16 and 26 May 1826 (AN (French national archives), MC/RS//249), provides an initial idea of the presentation of the collection in his apartment. Located on the first floor, the apartment looked out in part over the quay opposite the Louvre. The description of the collections housed in these rooms was analysed in depth by Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey in 1999 during the retrospective devoted to Denon (Dupuy, M.-A., 1999, pp. 392–400), which provides an initial glimpse of the incredible numbers of pictures, works, and cupboards filled with objects of all kinds, and furniture of varied provenances; an impression that Denon’s contemporaries always mentioned in their accounts of their visits to the expert’s home. Madame de Genlis (1746–1830) admired ‘the industrial products of the savages, their beautifully fashioned baskets, their coiffures, their belts, their fabrics made from tree bark and the filaments of various plants, with infinite art and skill…’ (De Genlis, S. F., 1825, VII, pp. 31–37). Lady Morgan (1776–1859), referring to a ‘Chapelle de Lorette des Arts’, saw ‘pictures, medals, enamels, bronzes, drawings, and curiosities from China, India and Egypt’, presented ‘in a philosophical and chronological order, with the aim of shedding more light on these distant epochs and demonstrating through several remarkable objects, the progress made by the human mind’ (Lady Morgan, 1817, II, pp. 77–90). Hence, from these—mostly enthusiastic—descriptions emerged the ambiguity of this cabinet, which oscillated between a taste for curiosity, inherited from the Enlightenment, and a recent interest in taxonomy. It reflected its owner, who during his long career in the service of the arts, travelled around part of the vast world and experienced various political regimes with an insatiable appetite for knowledge.

Having no direct heir and having decided not to bequeath his collection to a public institution, Dominique-Vivant Denon’s cabinet was sold by his nephews (Dominique-Vivant Brunet-Denon (birth date unknown–1845) and Vivant-Jean Brunet Denon, 1778–1866). The adjudications were held in his apartment in three stages. Initially, the sales of the pictures, drawings, and miniatures (987 articles) were held between 1 and 19 May 1826, then those of the antique, historical, and modern monuments, and Eastern works (1,390 articles) between 22 May and 13 June 1826, delayed until 15 January 1827; and lastly, those of the prints and figurative works (801 articles) with complementary objects (66 articles), scheduled for 12 June 1826, and delayed until 12 February 1827. The sale was accompanied by a Description des objets d’arts qui composent le cabinet de feu M. le Baron V. Denon , Paris, 1826, in three volumes (Tableaux, Dessins et Miniatures by A. N. Pérignon; Monuments antiques, historiques, modernes, ouvrages orientaux by L. J. J. Dubois; and Estampes et oeuvres à figures by Duchesne the elder).

The constitution of the cabinet

The pictures represent 222 articles, that is to say 224 pictures, of which around fifty have been identified to date (Dupuy, M.-A., 1999, pp. 437–438, and Perronet B., 2001, p. 746). The ensemble was far from providing a comprehensive overview of the history of painting, in contrast with the exhibition held in the Grande Galerie in 1810, but the objects selected by Denon followed this approach. He was committed to exhibiting the less well known and appreciated periods of the collectors of his epoch, such as primitive art, while going along with the taste—which was widespread at the time—for the Northern Schools (Hans Memling, Portrait of a Manwith a Roman Coin, Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp; Jacob Ruysdael, Landscape with Waterfall, Wallace collection, London). Aside from this major ensemble, the other Schools were less represented. Italian painting had few confirmed attributions, with the exception of a pair of portraits representing the Virgin and the Angel Gabriel by Fra Angelico (circa 1395–1455) (The Detroit Institute of Art), and two panels of Venetian caskets attributed to Andrea Schiavone (circa 1510–1563) (Musée de Picardie, Amiens). The French school was represented, amongst others, by Gilles by Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) (The Musée du Louvre), whose presence in the cabinet was considered atypical, and a Déploration sur le Christ mort by Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) (private collection), which was particularly appreciated by Denon (Dupuy, M.-A., 1999, p. 445).

More generally, it was the drawings that made up the ensemble that Denon was most proud of. Out of almost 1,400 drawings (Bicart-Sée, L., and Dupuy, M.-A., 1999, p. 452), priority was given to works by the great masters. Acquired during Denon’s Venetian sojourn during the Zanetti sale of 1791, the drawings of the Italian School were mainly executed by Guercino (1591–1666) and Parmigianino (1503–1540) (Bicart-Sée, L., and Dupuy, M.-A., 1999, p. 452). The Northern schools, comprising works by Rembrandt (1606–1669) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), were also well represented, as well as the French school, although the latter more modestly so. Denon’s passion for the art of drawing, which he too practised, cannot be dissociated from the art of engraving after the masters. His constant purchases in Italy and France, upon his return to the country in 1794, show the extent to which he saw this art as fundamental for the fine arts and as the basis for his own creative work. Denon like to associate his lots of drawings with the large volumes of engravings by Lucas Van Leyden (1494–1533), Rembrandt, and Jacques Callot (1592–1635), which also came from the Zanetti Collection.

The collection’s diversity was evident in the second adjudication of the Description des Objets d’art qui composent le cabinet de feu M. le baron V. Denon...Monuments antiques, historiques, modernes, ouvrages orientaux, etc. (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, 1826). It was significant that the catalogue of this section was drafted by the successor of Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) as the head of the Louvre’s Egyptian museum, Jean-Joseph Dubois (1780–1846), who acquired nineteen objects for the museum (Rigaud, P., 1999, p. 403).

The 422 Egyptian objects formed a very comprehensive ensemble and were distributed throughout the apartment (Rigaud, P., 1999, p. 402). The exhibition of six human mummies and several human remains, including a mummy’s foot, which was made famous in the eponymous novel by Théophile Gautier (1858), was one of the highlights of the tour of the cabinet. Denon purchased a large number of objects while he was in Egypt, but he could not bring everything back and had some difficulty in transporting large objects. All the same, he continued with his acquisitions in France in 1819 at the sale of the Malmaison Collection (nos. 160 and 244, Denon Sale) and in 1822 at the Jannier Sale (no. 239 and nos. 242–243, Denon Sale; see Rigaud, P., 1999, p. 402, notes 25–26). While the Egyptian civilisation—thanks to the deciphering of the hieroglyphs by Champollion in 1822—benefitted from decisive scientific recognition, the same could not be said for other lands. And yet, the Description mentioned after Egypt the Monuments babyloniens et persans, which only comprised five objects (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, 1826, no. 266 to 271, pp. 57–61), that is to say an Assyrian cylindrical seal, a neo-Babylonian stamp, and three Sassanid stamps (Demange, F., 1999, pp. 413–414). Everything suggests that Denon had acquired these objects in order to demonstrate their historical complementarity. The similarities between objects believed to have originated from distant geographical areas enabled him to convince those who saw his cabinet merely as the fruit of a curious collector of fine objects, that, even if he was not a scholar, he was at least a connoisseur. Indeed, the other major particularity of this collection was that it promoted objects from ‘exotic’ provenances, intended to open the minds of the collectors and whet the appetite of scholars.

With this in mind, Denon compiled a significant collection of so-called ‘Oriental’ works, ranging from ‘Arab and Persian’ objects to ‘Chinese’ works. Recent research has enabled some of these articles to be identifiedand associated with their places of production. In fact, the small number of ‘Arab and Persian’ objects documented in the Description (23), acquired in Cairo during the Egyptian campaign, does not give us a precise idea of Denon’s familiarity with the subject. Some of them—goldsmithery or marquetery objects—were commissioned by him on site.

More originally, the following category featuring in the sale catalogue describes ‘Hindu works’, represented by thirty-five objects (nos. 893–928) (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, pp. 202–211). They are separated into two categories: Sculptures et Armes and Dessins. In the first category are a certain number of bronze female statuettes representing Hindu divinities, one of which was identified by Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey as the goddess Vishnou (eighteenthcentury, Southern India), now held in a private collection (Dupuy-Vachey, M.-A., 2016, p. 346, fig. 8). The second category comprises eighty-nine miniatures grouped into lots, representatives of the divinities, portraits of sovereigns, and mythological scenes depicting no doubt the major epic themes in Hindu literature. Several clues suggest that Denon was quite familiar with Indian culture. Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey pointed out that he was made a member of the Société Asiatique (Asiatic Society) of Calcutta in a letter sent by its president dated 28 March 1816, the year of its establishment (Dupuy-Vachey, M.-A., 2016, p. 344 and note 60). While this nomination resulted from services rendered to English artists by Denon when was the Director of the Louvre, it cannot be excluded that his familiarity with this civilisation deepened when he was visited in 1819 by an eminent English specialist, Edward Moor (1771–1848), author of The Hindu Pantheon, published in 1810 (Dupuy-Vachey, M.-A., 2016, p. 346). Moor gave a copy of the book to Denon, and Dubois mentioned the work as a scientific backing for the objects chosen by the latter (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, 1826, p. 204, note 1).

Even more complex was the section ‘ouvrages chinois’ (‘Chinese works’), which listed 402 objects (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, 1826, pp. 211–294, nos. 929–1331), which made this ensemble one of the largest in the collection. The objects were classified according to techniques in nine categories: ‘Clay (46) and porcelain (99)’; ‘Cane, bamboo, sandalwood (29)’; ‘Steatite, horn, and ivory (17)’; ‘Bronze and copper (21)’; ‘Gold and other precious substances (24)’; ‘Lacquer (122)’; ‘Drawings and engravings (9)’; ‘Clothing and shoes (32)’; and ‘Various objects (10)’. Throughout the catalogue’s description no mention is ever made of the precise geographical provenance of these objects and the distinction between China and Japan, the main producers. Japan’s two-century long isolation obliged it to operate through Chinese or Dutch dealers on the island of Nagasaki.

Nevertheless, it is possible to get an idea of this ensemble, which comprised a profusion of small objects and furniture, sometimes beautifully made. Few objects have been identified to date. The first group of objects comprised coloured stoneware, enamelled earthenware, and decorative and China white porcelains (Préaud, T., 2001, p. 658), complemented by thirty-nine carved figurines, including Chinese magots. Denon, in particular, bought objects at the Robit Sale held in May 1801 (Préaud, T., 2001, p. 658) and at the sale of the Secretary of State Bertin in 1815 (Préaud, T., 2001, p. 658). It is also known that he donated Japanese objects to the Musée de Céramique in Sèvres in 1808 (Préaud, T., p. 658).

The bronze vases are described in pairs. No chronological indication specifies their date of manufacture and the dynasty they are connected with, with the exception of an oblong perfume vase, placed on a four-legged plateau, on which a date is marked (Dubois, J.-J., Paris, 1826, p. 249, no. 1 940, note 1). A note specifies that it dates from the fifteenth century during the Ming Dynasty (‘Xuande 1425–1435’). Likewise, a golden box was described as a masterpiece in a perfect state of conservation (Dubois J.-J., Paris, 1826, no. 1146).

This ensemble also included the collection of Japanese lacquered objects, which included several major pieces identified by Geneviève Lacambre during her pioneering research (Lacambre, G., L’Or du Japon, exhibition catalogue, Bourg-en-Bresse, Arras, 2010, pp. 47–57). She highlighted the vitality of commerce in France during the Empire and the Restauration as a result of the sale of prestigious collections. Already, during the Revolution, the precious collection of lacquered objects belonging to Queen Marie-Antoinette d’Autriche (1755–1793) had been miraculously recuperated by the Muséum, some of which was later added to the collections of the future Musée de la Marine (Lacambre, G., 2010, pp. 49–50). For himself, Denon bought objects in the public sale of the cabinet and shops of the dealer Philippe-François Julliot (1755–1836), on 22 March 1802 (Lacambre, G., 2010, p. 52 and Lacambre, G., BSHAF, 2014, p. 13). The catalogue comprised twenty-six lots of Curiosités en laque du Japon et de la Chine, for which he competed with William Beckford (1760–1844), a major collector of lacquered articles, intended for his English residence of Fonthill Abbey (Lacambre, G., 2010, p. 52). Geneviève Lacambre suggested a Denon provenance for a jewellery casket from the Duthuit Collection (Musée du Petit-Palais, Paris, inv. no. Dut.1494—cited in Lacambre, G., 2010, cat. s14, fig. 24, p. 43, and Lacambre, G., 2014, p. 14 and note 68). Beckford acquired another Japanese casket at the Denon Sale on 15 January 1827 (no. 1204) , which is now held in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Lacambre, G., 2010, p. 54, fig. 35, and MADV, 2016, p. 349, note 69) and may have come from the Ducs de Bouillon, that is to say in a direct line from the Mazarin heirs (Lacambre, G., 2014, p. 14). A Japanese cabinet was also mentioned by Hélène Bayou in 1999 (Bayou, H., 1999, p. 424, cat. 490, private collection), corresponding to no. 1292 in the 1826 catalogue (Dubois, J.-J., Paris,1826).

Aside from trunks and caskets, three lacquered boxes from the second half of the eighteenth century, purchased by Denon, are now held in the Département des Objets d’Art in the Musée du Louvre, in the Thiers Collection, which was bequeathed to the museum in 1881 (Lacambre, G., 2010, cat. 22, 25, 69. Boîte à documents, inv. no. TH 413; Boîte en forme de double ovale, inv. no. TH 407; and Boîte sphérique à savonnette, inv. no. TH 403, Musée du Louvre).

The extra-European collections assembled by Denon did not end there. Indeed, the section Mélanges in the catalogue comprised works from America and Oceania (Dubois, J.-J., Paris,1826, pp. 294–301, nos. 1332–1367, 35 lots). Although the attributions given by Dubois were incorrect (Bresc-Bautier, G., and Guimaraes, S., 1999, p. 428), they did not dissuade the buyers from flocking to the Denon Sale. A movement of collectors and scholars ‘encouraged the royal administration to create a museum of savage peoples in the Louvre’ (Bresc-Bautier, G., 1999, pp. 428–429) and consequently to purchase certain lots documented in 1829 in the État des objects fabriqués par divers peuples de l’ancien et du nouveau continent achetés à la vente du feu Monsieur le Baron Denon (AN/O3/1427).

The panorama of Dominique-Vivant Denon’s Collection would be incomplete if one neglected to examine the ‘Western’ collections of this second part, which predominated in the cabinet. They point to a distinct development between the first acquisitions made in Italy, such as the collection of antique vases purchased by the king in 1786 and the collection of coins and medals, and those that followed the revolutionary period. Although Denon remained attached to Graeco-Roman culture, he also explored the ‘dark’ centuries of the Middle Ages with the purchase of several fine specimens of silver and goldsmithery, enamel, and carved ivory articles, amongst others, which came from European workshops (Chancel-Bardelot, de B., 1999, pp. 418–419). He belonged to what Béatrice de Chancel-Bardelot described as the first generation of unscrupulous collectors of medieval art, such as Lenoir, Edme Durand, and Pierre Revoil (Chancel-Bardelot, de B., 1999, p. 419), which places Denon’s tastes at the turning point of two centuries.

In quest of a universal history of art

When he left the Louvre in 1815, Denon sought to use his collection to create a ‘history of art from the most ancient times until the present day’. He began by making lithographic reproductions of certain objects in order to create a sort of encyclopaedia, juxtaposing formal comparison and the technical progress of the various cultures with articles. His cabinet became famous beyond the frontiers of France, as attested by his links with English scholars, such as Thomas Frognall Dibdin (1776–1847), Dawson Turner (1775–1858), Edward Moor, and German scholars, such as Alexandre van Humboldt (1769–1859), who all supported him. All the same, nothing was published during his lifetime and it was his heirs who entrusted Amaury Duval (1760–1838) with the task of completing the four-volume work. It is not certain that the title selected, Monuments des Arts du Dessin, reflected Denon’s thinking, but, it did reflect Amaury Duval’s more theoretical viewpoint, that of a general history of the arts, in which the role of the collected object was not at the forefront, in contrast with Denon’s wishes (Steindl, B., 2001, La Documentation graphique sur la collection de Vivant Denon et les Monuments des arts du dessin. Un essai de reconstitution, pp. 769–799). This was clearly influenced by L’Histoire de l’Art par les Monuments published by Jean Baptiste Louis Georges Séroux d’Agincourt (1730–1814) between 1810 and 1823 (Steindl, B., 2001, p. 772).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne