FRANDON Ernest and LE PROVOST de la VOLTAIS Gabrielle (EN)

Biographical article

A First Career in Law and Journalism

After earning a law degree in 1864, Ernest Frandon began his career as a lawyer. He was interested in cooperative societies,a subject to which he devoted a book (Frandon E., 1868). With the help of contemporary figures including Jules Simon (1814-1896), former Minister of Public Instruction, Auguste Casimir-Perier (1811-1876), former minister and senator, and Léon-Jean-Baptiste Say (1826-1896), economist and politician, Ernest Frandon founded "L'universelle", a company intended to encourage cooperative institutions in France, which went bankrupt in 1870 (Bensacq-Tixier, N., 2003, p. 236).

During the war, Frandon joined the Mounted Chasseurs. Through his acts of bravery in combat, he gained military distinctions (AN, LH//1029/41).

After the war, Ernest Frandon made several trips, first to Germany to study popular banks, then to Herzegovina, following the Prince of Montenegro, his former classmate at Louis-le-Grand. He followed the campaign in Herzegovina and then the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878 for various newspapers (Bensacq-Tixier, N., 2003, p. 236).

Delayed Start of a Diplomatic Career

In 1879, Frandon made a request to begin a consular career. He began as a chancellery clerk at the French consulate in San Sebastian in November 1879 before being sent to Asia, first to Yokohama and then to Shanghai (AMAEE. FRMAE 394QO/643).

Frandon then continued his career in Fuzhou, in the province of Fujian, in southeastern China. The vice-consul was first noticed by his energetic efforts in favour of the city’s Christians, during the riots that occurred in 1883. Frandon “brought his litter, took his revolvers and went with his servants to the place of the riot. It took nothing less than his audacity and his unfailing composure to dominate the situation. They did indeed try to tear his litter to pieces, but at the sight of the armed servants and especially of the revolver which the consul threatened to use against the first who would arrest him, they let him enter the Church. There he managed little by little to calm the storm, and to inspire some fear in the crowd, which ended by withdrawing.” (article from L’année dominicaine quoted in AN, LH//1029/41).

A Committed but Spendthrift Diplomatic Agent

During his stay in Fuzhou in 1883 and 1884, Frandon also came to the aid of the French fleet led by Vice-Admiral Courbet (1827-1885). The fleet was then engaged in the Tonkin expedition, the purpose of which was to strengthen the French presence in the Indochinese peninsula. It was a matter of settling in the provinces of Annam and Tonkin, despite hostility from China. Frandon played the role of intelligence agent by noting the passes of the Min River, the position of the forts, and the number of vessels. To do this, he benefitted from Chinese complicity susceptible to corruption, but also committed himself personally, by spending a month in a boat on the river, including at night, to carry out the most precise surveys possible. He thus managed to draw up the plans of the Chinese positions and also noted the number and type of weapons used (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 172). All of this information enabled the vice-admiral to bombard the port and arsenal of Fuzhou in August 1884 without damage to the French fleet. In addition to intelligence, the vice-consul also provided Admiral Courbet with interpreters and pilots.

While his services to the fleet and support for French colonial ambition were praised by his superiors, Frandon faced repeated accusations of extravagance. He was often reproached for the bad use made of credits allocated for service costs, first in Shanghai, then in Fuzhou and Kobe, where he was posted from 1886 to 1889. His superior in Shanghai told him as early as 1882: “(…) As for expenses exceeding the maximum, they are divided into foreseen and unforeseen expenses. Fees belonging to the latter class must henceforth be avoided at all costs. Moreover, all expenses are in principle subject to the prior approval of the head of post.” (Quoted by Bensacq-Tixier, N., 2003, p. 237).

Marriage to Gabrielle Le Provost de la Voltais and the Creation of a collection in China

Aged 43, Ernest Frandon took advantage of a stay in France in 1885 to marry Gabrielle Le Provost de la Voltais, daughter of Count Fernand de la Voltais. She came from a family of minor Breton nobility and was twenty years his junior. She followed him to Kobe, Japan, where he was assigned in 1886, then to Fuzhou from 1889. Life in southern China at that time was difficult. In 1891, the consulate was threatened by riots. In 1892, one of the couple's daughters died of illness, whereas the second hovered between life and death from August to September. The couple also hosted two young French travellers, Manuel Suberville and the son of the Marquis de Bartélemy. The first died of typhoid fever; the second was saved thanks to the care provided in particular by Madame Frandon. (Quoted by Bensacq-Tixier, N., 2003, p. 239).

Frandon ended his career in France, where he was entrusted in 1900 with a mission to develop commercial relations between France and China, before his retirement in January 1901 (AMAEE. FRMAE 394QO/643).

Following his death in 1904 in Marseilles, his widow insisted to the ministry that her late husband be recognised with the honoursbefitting his title of Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (AN, LH//1029/41).

The collection

A Collection Gathered for Documentary Purposes

During their stays in Asia, the Frandon – de la Voltais couple gathered an important collection of objects primarily from southern China. The constitution of this collection was part of the economic and commercial missions assigned to the consuls abroad. Theywereexpected by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to transmit all commercial information likely to contribute to the development of French trade. They had to learn about the products that were susceptible to interest the Chinese and to write reports helping promote French exports (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 178). Consuls were encouraged to send samples to France that were likely meant to provide information on the needs and habits of the Chinese so that French persons wishing to do business in the region would be able to adapt their products (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 179).

Samples to Commercial Museums in France

To meet this demand, the government favoured the creation of commercial museums in the 1890s, in order to encourage French industrialists to fight against English competition and to adapt to the tastes of Asian populations. Among these museums, theMusée commercial et colonial de Lille, founded in 1885 under the patronage of and with the assistance of the Ministry of Commerce, the city of Lille, and the Chamber of Commerce of Lille, opened its doors in 1888. Its purpose was to bring together collections of samples, with information (manufacturing, selling and purchasing prices, packaging methods, etc.), to "submit them to French manufacturers, let them know what is sold in the main places of commerce and thus facilitate the export of their products.” (Notice sur le musée commercial et colonial de Lille, Lille, 1898). In 1895, Frandon sent the museum three boxes containing two photo albums and more than 150 objects: fabrics, costumes and jewellery, pipes, brushes, tools, kitchen utensils, and toys testifying to the habits and customs of the country. All itemswere accompanied by a detailed report (Vandecasteele-Vandenberghe D., 2004). Among these objects was a yellow silk mandarin robe, now kept at the Musée d’histoire naturelle de Lille (NNBA 7255). The array of items sent by Frandon constituted a thorough and representative sample of the objects to be found in Fujian and in southern China at the time.

Frandon also took photographs of these objects, which he collected in albums, one of which was offered to the library of the Musée Guimet (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 178). Frandon sent other samples to the Musée commercial de Bordeaux, as well as to the Musée des arts et métiers (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 179).

Shipments to Natural History Museums

The Muséum d’histoire naturelle and the Jardin d'acclimatation also received shipments from the consul, including seeds, plant specimens, live fish, and fish preserved in alcohol (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013 , p. 179).

Commercial museums as well as other museums with broader purviews had theoretically committed to reimbursing the expenses advanced by the consuls in creating these collections (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 179).

The Collection of Ceramics

Suchwas not the case for the significant collection of ceramics, amassed in Fujian by the consul and his wife, who spent lavishly to the point that the ensuing debts forced the couple to mortgage the property that Madame de la Voltais owned in Brittany (Bensacq-Tixier, N., 2003, p. 239).

Frandon was described by a contemporary as “a distinguished collector, a dilettante of all things art. Monsieur Frandon has a collection of porcelain to rival that of the finest museums” (Mariani A., 1901). In reality, it wascomposed of relatively common pieces purchased in southern China or Canton.

Frandon proposed the acquisition of this collection to the city of Paris (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 178): "It is essential that these models remain at the disposal of our artists and not pass to their foreign competitors. I would be happy to provide them free of charge. In the fifteen years that I have had the honour of followingthis career, I have donated numerous objects to the museums of the Trocadero, Sèvres, Guimet, Jardin des Plantes, and the Acclimatation, proving that I am not a speculator. Passionate about a matter that I considered useful, even patriotic, I devoted most of my wife's fortune to it. I gladly offer up these assets, which are mine .” (Quoted by Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 179).

This collection was also offered by Frandon to the Musée Guimet through a half-donation/half-purchase arrangement: "I would transfer pieces free of charge up to half the value fixed by the experts.” (Quoted by Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 178). In the end, the Musée Guimet accepted only a few objects: Chinese volumes, a manuscript on Chinese pavilions, an old kakemono, a wooden and ivory painting, and 20 Japanese porcelains (Bensacq-Tixier N., 2013, p. 178), as well as bronzes (AN/M/MT/20144787/14).

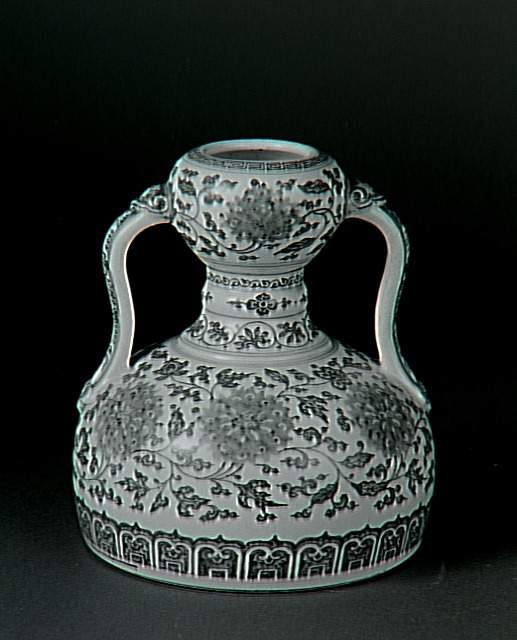

Frandon then turned to the Sèvres manufactory, whose museum of ceramic arts, created in 1806 by Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), brought together examples of ceramics from all countries. The manufactory showed interest and 841 pieces entered the museum's collections in 1894. These were followed by several other purchases or donations until Frandon's death in 1904 and catalogued in a specific inventory, under the call number of MNC 10169, which has 1264 sub-numbers (Brouillet S., 2013). The vast majority of these pieces originated in southern Chinese kilns (Shiwan, Fujian), whereas some others came from Jingdezhen, Dehua, or Japan.

For the manufactory, the technical aspects of these pieces was the main source of interest . It was amatter of understanding the manufacturing techniques in order to be able to reproduce them within the factory. Thus, some of the pieces acquired from Frandon were intentionally sawed open, so that the pigments could be studied. Such was the case, for example, for pieces with a celadon glaze, or the deep red “sang-de-bœuf" pieces that the factory had been trying to reproduce since the middle of the 19th century (Salvetat A., Recherches sur la composition of materials, 1852 and Salvetat A., "Essais par analyse et synthèse sur le rouge au grand feu des Chinois par M. Salvetat", Archives MNS, Carton N2, dossier Salvetat).

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres - Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne

Personne / personne