CURTIS Atherton (EN)

Atherton Curtis

Eldest son of George N. Curtis and Eliza Meecham, Atherton Curtis was born in Brooklyn, New York to a wealthy family on August 3, 1863 (according to his 1915 marriage certificate (AP, 6M231, 07/01/1915), other sources state April 3). They amassed their wealth during the second half of the 19th century, producing Mrs Winslow's soothing syrup for children. It was banned from the market around 1930 because it contained morphine. Like his younger brother, George Warrington Curtis (1869-1927), who would devote himself to sculpture, Atherton showed a keen interest in art. He would devote his life to art and philanthropy which is possible to follow thanks to the diaries, kept in the Département des Estampes et de la Photographie (BNF EST , Res. YG-187-8). A vegetarian and very adverse to the suffering of animals, he was a patron of the Humanitarian League of Henry Stevens Salt (1851-1939) and financed the publication, between 1900 and 1910, of the Humane Review, a quarterly of the League (The Routledge history of food, 2014, p. 196).

He lived in Paris around 1890 and frequented artistic circles. He married Louise Burleigh (1869-1910) on August 14, 1894. The couple lived in the Montparnasse arrondissment, 5 rue Boissonade and shared a common passion for prints, having both collected prior to their marriage. Started during his years as a student at Columbia University, Curtis' collection diversified over the years to include antique prints, works by engravers of the 19th and 20th centuries, Japanese and Chinese production accumulated in his catalogue to reach some 8,000 Western coins and 2,000 Asian sheets upon his death (BNF, EST, Res. YE-289-PET FOL).

In 1900, the Curtis’ left France and purchased a house in Mount Kisco, 70 km north of New York City. Atherton commissioned architect Robert D. Kohn (1870-1953) to add a fireproof building to house his collections as well as a guest house to accommodate researchers and connoisseurs (BNF, EST, Res. YE -289-PET FOL). He allowed the small town to benefit from his generosity having endowed it with a municipal library and having funded road works at his own expense. He also received artists for more than three years and opened two exhibitions to the public of his Rembrandt engravings from July to October 1902 and those by Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910) from November 1902 to March 1903. He recorded these two presentations in the publication of two small catalogues: Catalogue of Prints & Drawings by Rembrandt, and the Catalog of Etchings, Dry-Points and Mezzotints by Francis Seymour Haden, both belonging to the Curtis Collection, New York, Mount Kisco, 1902.

Disappointed by the town’s lack of enthusiasm, Louise and Atherton Curtis returned to Paris in 1904. The Mount Kisco house was sold. The collections, which now included works of art and archaeological objects, were then housed at 17 rue Notre-Dame des Champs, an address where Curtis would live until his death. Louise died in December 1910 after an illness. He would wait five years to remarry Ingeborg Flinch (1870-1943) on July 1, 1915 (AP, 6M231).

From then on, Curtis lived between his Parisian home and his residence in Bourron-Marlotte on the edge of the forest of Fontainebleau, where he welcomed family, friends, connoisseurs and artists. Faithful to his principles as a philanthropist, he financed the creation of a municipal library in Bourron and, in 1930, a kindergarten (Roesch-Lalanne, 1986, p. 17-18). Based on his vast collection and on the funds of the Cabinet des Estampes of the National Library, he published several works, in particular on his favorite subject; lithography.

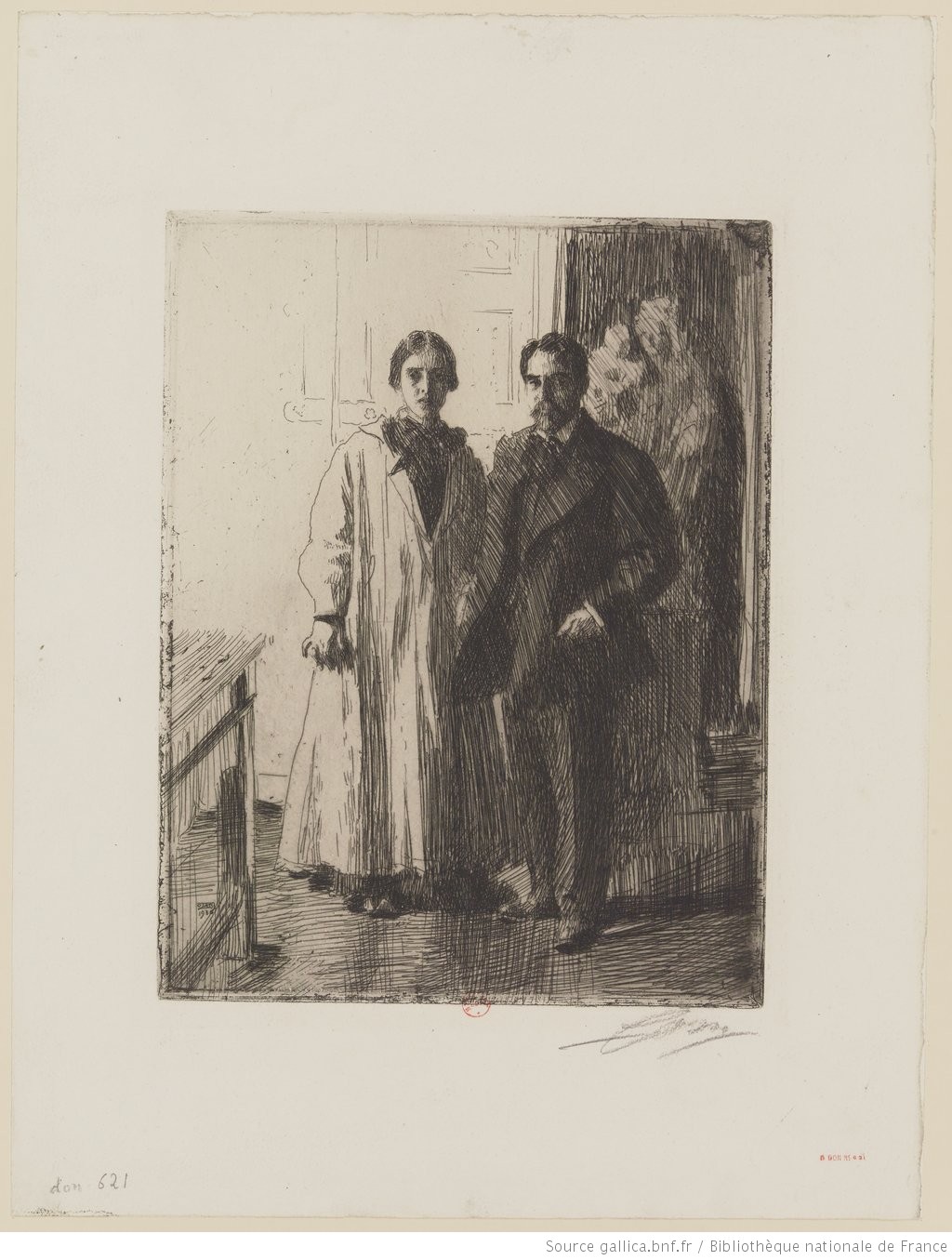

Curtis didn’t just amass exceptional pieces. He also liked to support artists. This is how he formed a long-lasting friendship with the African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), whom he met in Paris in 1897 (Woods N.F., p. 152). The correspondence between the two men attests to their solid bond and the unfailing support from Curtis. The painter-engraver Amédée Joyau (1872-1913), heavily influenced by Japonisme, was also supported by Curtis. In 1938, Curtis published the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s works and in 1938 ensured that the artist's wood matrices were safe within the walls of the Bibliotèque Nationale. He also encouraged the ceramist Émile Decoeur (1876-1953) through his numerous purchases, whose models were influenced by China and matched Curtis’ taste for the Far Eastern. Portraits of Curtis by the engraver Andres Zorn (1860-1920), the painter William Nicholson (1872-1949) and, of course, Tanner testify to his importance in the art world for the first half of the 20th century.

From 1938, the Curtis’ began to consider the future of their collections. Since several American and European museums already had benefitted from their donations, they chose to donate the majority of their collection to France. On April 2, 1938, the Conseil des Musées nationaux accepted the Curtis donation, of certain pieces and subject to usufruct, that combinded Western and Far Eastern works with more than a thousand Egyptian archaeological objects (AN., 20150044 /79, April 12, 1939 with list of donated objects). Then, in a will dated July 10, 1939, Curtis and his wife bequeathed, also subject to usufruct, several thousand prints to the Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliotèque Nationale, including all of their 2,000 Chinese and Japanese pieces (BNF, IS, Res. YE-289-PET FOL).

Curtis died on October 8, 1943 followed by Ingeborg on the 11th. The great Parisian print dealer, Paul Prouté (1887-1981), a close associate of the couple and also the executor of their willl (P. Prouté, 1981, p. 38-41), declared the two deaths (AP, 6D252; BNF, EST, Res. YE-289-PET FOL).

A lot of 92 boxes of the Curtis’ donations were sheltered during the Second World War, with certain of the Louvre collections, at the Château de Courtalain (Eure-et-Loir), and then gradually distributed to the Parisian institutions where they were intended after 1945 (BNF, EST, Res. YE-289-PET FOL). Today, the Louvre, the Musée de Cluny, the Musée Guimet, the le Musée national d’art moderne, the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France house what was once of the finest collections of the first half of the 20th century.

Louise Burleigh and Ingeborg Flinch

Born into an old, established family in Maine, Louise was the daughter of Daniel Coffin Burleigh (1834-1884), a military doctor who settled in Europe from 1880 (Burleigh, 1880, p. 105). She lost her father in Dresden in 1884 (Holloway, 1981). She studied with the painter Luc-Olivier Merson (1846-1920) and the engraver Evert van Muyden (1853-1922) while living in Paris with her mother Anne Curtis. She died in Paris on December 17, 1910 (AP, 6D169).

Eldest daughter of the Danish actor and writer Alfred Carl Johannes Flinch (1840-1910), Ingeborg was a watercolorist and was among the exhibitors at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. In 1903, she worked for Atherton Curtis and his first wife as their secretary (BNF, Prints and photography, Journal of Atherton Curtis), before marrying Curtis in Paris on July 1, 1915 (AP, 6M231). She died, two days after her husband, on October 11, 1943 (AP, 6D252).

The collection

The Asian section of the Curtis collection has many beautiful objects now kept at the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques – Guimet. Among them is a late 16th century Japanese inrô from the Edo period (MNAAG, n.inv EO 1034) and two Chinese porcelains from the Tang period (MNAAG, n.inv. MA 806 and 807). The collection stands out above all due to its it is portfolios of Japanese and Chinese prints. They were all bequeathed to the Département des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale in 1938. Approximately 2,000 pieces were moved to rue de Richelieu in 1946, where an inventory took palce between 1947 and 1949 catalogued by Jean Buhot (1885-1952) (BNF EST, Res. YH-478-4). It was officially registered on November 14, 1949 (entry mark: D. 7374). The most beautiful pieces have appeared in several exhibitions held by the department (in 1951, “The Curtis collection, prints and drawings by Old Masters bequeathed to the National Library by the great American amateur”; in 1992, “Impressions of China; in 2008, Japanese prints, images of an ephemeral world”).

Curtis brought together his collection of Japanese prints between 1896 and 1906. They were acquired from the main Parisian dealers (194 pieces bear the mark of Siegfried Bing), American and Japanese dealers as well as at auctions of such prestigious collections as that of Pierre Barboutau (Lambert, p. 5). Encompassing 798 proofs (BNF EST, Res. DE-10-BOITE ECU), it offers an almost complete panorama of Ukiyo-e, its techniques and its formats, and completes the important Japanese collection of the Département des Estampes, with numerous high quality proofs. It represents thirty-five artists, from Hishikawa Moronobu (ca 1618-1694) and his black and white engravings to Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) with a majority of his works dating from the the end of his life. The latter also includes the matrix on wood Abe no Nakamaro from the Shika shashin kyô series (1833). The collection celebrates the 18th century with masterpieces by Suzuki Harunobu (ca. 1725-1770) and Kitagawa Utamaro (ca. 1753-1806). Note that in the Japanese part of the collection these is a copy of the Hyakumanto (Million Pagodas), a Buddhist text, printed from 764-770 inserted inside a small wooden pagoda (BNF EST, Res. MUSEE-OBJ -199). The object was chosen by the dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853-1906) at the Hôriûji temple in Yamato and appeared in the collection of Henri Vever (1854-1954).

Curtis seems to have taken an interest later in Chinese prints, which he acquired as of 1936 (Prinet, p. 13). With the Curtis collection, nearly 1,200 pieces, in sheets or appearing in more than 100 illustrated books, joined the Chinese pieces of the Départment. It was founded in the 18th century and later expanded by the acquisition of the collection of Jules Lieure in 1943 (1866-1948). Within the Curtis collection, there are excellent examples of Buddhist books, such as a Qisha zang (Buddhist canon from the island of Qisha), in twelve booklets, produced between 1231 and 1363 (BNF EST, Rés. OE- 232 to 238-4) or the rich 1581 imperial edition of the Sutra of flowery ornamentation (BNF EST, Res. OE-241-4). One of the rarest works in the collection is undoubtedly the Splendors of West Lake and Mount Wu album, dating from the first third of the 17th century which includes eleven woodcuts printed in blue and red on a lined black board. It also has calligraphy engraved on wood that celebrate the beauty of the surroundings of the city of Hangzhou (BNF EST, Res. DF-1-BOITE ECU). There are also very fine proofs of Kaempfer prints (Suzhou, end of the 17th century) and of stone engravings from the Ming and Qing periods, such as the Album of Impressions from the Forest of Zhou Paintings (period Ming, Wanli period, BNF EST, Res. OE-262-4) and the Meeting during the Purification Festival at the orchid pavilion (Qing period, BNF EST, OE-273-ROUL).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une famille

Personne / personne

Personne / personne