Compagnie française des Indes orientales (EN)

A Compagnie des Indes was a commercial company enjoying certain privileges, particularly that of operating as a monopoly, regarding trade between a country in Europe and another a distant region, primarily the Americas, or the West Indies, and Asia, or the East Indies.

Several Compagnie des Indes emerged at the beginning of the 17th century, first the English (1600-1858), followed by the Dutch (1602-1795), then the Danish (1616-1772). The French Compagnie des Indes was created in 1664 by Louis XIV (1638-1715) and Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), thus arriving late into a very competitive market (Sottas J., 1994, p. 7-14; Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 5; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 23-27; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 28-41; Castelluccio St., 2014, p. 228 -231). Its management included a chambre générale or main office based in Paris made up of twelve directors, and four provincial offices in Bordeaux, Nantes, Lyon, and Rouen. A minimum contribution of 20,000 livres allowed one to be elected director by the shareholders who themselves contributed a minimum of 6,000 livres. At least three quarters of the merchants were expected to be on the direction centrale or main board, but participation of two members from the same family was refused. The company's main port and outfitting port was based at Lorient (AN, col/C/2/2, f° 48-48 v°. Sottas J., 1994, p. 10-11, 20-22 Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, pp. 19-45, 95-139; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 42-47, 96-117).

Over time, the Parisian management proved to be too bureaucratic, timorous, and incompetent in commercial and maritime matters. In addition, the overbearing presence of the state led to decisions whose political, colonial, and religious motives often opposed the commercial interests of the company, such as the disastrous colonial policy of Madagascar. In addition to these setbacks, the war with Holland considerably hampered maritime trade from 1672 to 1678, to the point of indefinitely compromising the financial security of the company (Sottas J., 1994, p. 15-16, 26-27 , 36, 40, 44-45). The company was never able to arm a fleet large and powerful enough to ensure return trips regular and substantial enough to generate a yearly profit. In the 1670s, one to three ships came back each year; in the following decade, up to five; then the numbers fell back to three and less. At the same time, the Dutch company sent between ten and twenty-five ships annually (Dufresne de Francheville J., 1738, III, p. 11).

At the beginning of the 1680s, the Compagnie des Indes saw itself financially exhausted, to the point that in a decree of the Council of January 6, 1682, Louis XIV opened up trade in the East Indies to private individuals, on condition that they use the ships of the Compagnie des Indes. (AN, col/C/2/5, f° 31). Although the Compagnie ceded a part of its monopoly, it retained two prerogatives: the exclusive right of navigation to India, which enabled it to collect a tax on the cargo of individuals, and the exclusive right to sell the imported goods, both of which were required to be stocked with the cargo brought back on behalf of the company. The exception concerned the stocking of pearls, diamonds and precious stones which were returned to their owners upon arrival of the vessels (AN, col/C/2/5, f° 31. Dernis, 1755-1756, I, pp. 355-358; Sottas J., 1994, p. 72; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 47-50).

Finally faced with the deplorable financial state of the Compagnie des Indes in 1685, the directors applied a drastic savings program reducing personnel to the bare minimum and retaining only the sites of Lorient in France, Surate, Pondicherry and Chandernagor in India, and the many the trading posts of Bantam, Tilcery, Rajapour, and Masulipatam (AN, col/C/2/5, f° 72-75, 76 v°-77 v°, 119-137, 138-140 Sottas J., 1994, pp. 78-84; Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, pp. 47-50; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 142-157, 166-171). Subsequently, the twelve directors were no longer elected by the other parties involved, but appointed by the king from among the shareholders who had contributed at least 30,000 livres of capital. Louis XIV wanted the management of the Compagnie in the hands of a small group of people whose fortune would allow them to finance any future needs in funding. The sovereign expected that none of them would give up their large capital, in the case of serious difficulties. The former Parisian directors lost their positions, while the regional chambers, deemed too costly, were abolished. Louis XIV retained the monopoly and privileges of the old Compagnie himself, as well as prohibiting any transport of private goods on its vessels. (AN, col/C/2/3, f° 184-189 v°. Sottas J., 1994, pp. 86-90). However, the War of the League of Augsburg hampered trade to India from 1688 and consequently did not improve the Compagnie’s financial situation.

Peace, a consequence of the Treaty of Ryswick which put an end to the conflict in 1697, favored trade for the Compagnie des Indes. However, due to lack of resources, it had to borrow funds for each shipyard for five years. Still the profits were not enough to repay loans and interest. The Compagnie's situation worsened with a fatal blow dealt by the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1713) (Sottas J., 1994, p. 403-434).

In the fall of 1697, shipowner Jean Jourdan de Groucé was contacted to outfit a ship for China, a country yet to be exploited by the Compagnie des Indes, as a subtle way to circumvent their monopoly. He obtained the support of Minister Jérôme de Phélypeaux, Count of Pontchartrain (1674-1743) and outfitted the Amphitrite, sailing on March 6, 1698 and returning on August 13, 1700. The sale of the goods was held on October 9 and 11 in Nantes (AN, col/C/1/17, f° 44-45 v°. Mercure galant, September 1700, p. 205-213; Madrolle C., 1901, p. 73; Belevitch-Stankevitch H., 1910, pp. 49-71; Sottas J., 1994, p. 406; Croix A.-Desroches J.-P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, pp. 26-30, 50-51; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 51-55, 220-221; Castelluccio St., 2019, p. 48). The monumental feat of the voyage, the distinction of being the first to reach China, the profits they generated, the dividends paid to shareholders, and the many products brought back all had a lasting impact on people's minds. (Mercure galant, September 1700, p. 205-213 and August 1703, p. 327-329; Savary des Bruslons J., 1723-1730, art. “Compagnie de la Chine”, “Course”, “Robes”, “ Soyes de la Chine”, “Thé”).

At the same time, the combination of the War of the Spanish Succession and the loans made for outfitting, exhausted the last reserves of the Compagnie des Indes. The final voyages of the Maurepas and the Toison d’or were in 1706, returning in 1708, followed by the Saint Louis that returned the following year. Now unable to man any ship, the directors of the East India Company leased their Asian navigation and trade monopolies to la Compagnie de la Mer du Sud in 1707. They signed a treaty with the latter’s directors, who authorised them to send vessels to India, on condition that they pay 10% of sales of the goods brought back and 5% of those coming from the spoils of war to the Compagnie des Indes. In exchange, the latter placed its warehouses and clerks in India at the disposal of the Compagnie de la Mer du Sud. None of the vessels nor returned goods belonged to the Compagnie des Indes (Sottas J., 1994, p. 437-456; Castelluccio St., 2014, p. 227-242).

The Compagnie de la Mer du Sud was founded in September 1698 and headed by “Malouin” Noël Danycan de l'Épine (1656-1735). Jean Jourdan de Groucé also had shares in the Compagnie de la Mer du Sud, whose goal was trade with the Pacific, and more specifically with Peru, with return travel via China. The company developed successfully in the hands of the very enterprising “Malouins” from 1702 to 1713, the year of the Treaty of Utrecht which also closed trade in the Spanish colonies to foreigners (Dernis, 1755-1756, I, p. 650-660). At the same time, trade with Asia experienced an unprecedented development. Around 1700, the Chinese government authorized foreign companies to enter China, with Canton as the only port open to foreign merchants (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999 , pp. 51-52; Croix A.-Desroches J.-P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, pp. 36-39, 54-55; Estienne R., 2013, p. 172 -177). This gave them first-hand access to the market. This also made it possible to widen the selection of goods as well as to place orders directly with manufacturers and to request particular shapes and decorations adapted to European tastes and uses. At the same time, the major European companies dramatically increased their import volumes.

From 1719 to 1725, financier John Law (1671-1729) joined the Compagnie Française des Indes and integrated it into his ambitious financial operation or "System", as a guarantee for the bank created in parallel to absorb the very large debt of the State. The company survived the fall of the system and experienced a revival of activity from 1731. This was due to the reforms of Comptroller General Philibert Orry (1689-1747), who limited its activities to commercial exchanges between France and Asia and reduced the number of shareholders by having part of the shares purchased by the Royal Treasury. The King was thus the main shareholder, and the management was simplified with only six directors, appointed by the King from among the merchants and shipowners of the major ports, as well as an inspector or commissioner, who oversaw the management of the company on behalf of the King. As of 1745, two commissioners were appointed to the Minister of Finance, as well as a maître des requêtes.

The Seven Years' War disrupted the trade of the Compagnie des Indes. In 1764, it tried to resume its commercial activities by appealing to the Royal Treasury and borrowing funds, but faced with a difficult financial situation in 1769, contrôleur général Étienne Maynon d'Invault (1721-1801) and Minister Étienne François de Choiseul (1719-1785) suspended its exclusive commercial activity with Asia. All shipowners now had the freedom to trade beyond Cape Town, provided they return to and sell their cargoes in Lorient. After a transition period, trade volume increased steadily as of 1773. However, the free trade conducted by private individuals was accused of lacking funds for the dispatch of large fleets, raising prices in India and transferring money to Asia, and reducing the variety of imported products.

The plan to re-establish a Compagnie des Indes monopoly was brought to the table and became effective thanks to contrôleur général Charles Alexandre de Calonne (1734-1802). A third Compagnie des Indes was officially created in April 1785, with Lorient as its home port. Its monopoly ran for seven years, a period then extended to fifteen years in 1786. However, this new company was met with the hostility of private shipowners, who then lost its commercial monopoly in 1791 followed by its liquidation in 1795 (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, pp. 5-16; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 33-161 and II, pp. 751-815; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 56-83).

Travel Conditions

The vessels were to set sail from Europe between November and March to take advantage of the equatorial trade winds along the African coast. The easiest manner of avoiding the headwinds and the flats of the Gulf of Guinea was to approach the coasts of Brazil, a longer but safer route. Navigating the Cape of Good Hope was often difficult due to frequent storms. The easiest route to reach India required vessels to leave from Europe at the beginning of winter and after five months of navigation take the Mozambique Channel, avoiding the end of July monsoon. The monsoon went on longer east of Madagascar, where a break was possible on the Island of France or Bourbon, present-day Mauritius and Reunion Islands.

For a direct voyage to China, navigators took the strong winds of the 40° parallel then turned towards North. This route was possible in all seasons, but required non-stop navigation for two to three months. One then had to cross the Indonesian archipelago, either by the Sunda Strait, risky, because shallow (8 meters for an average draft of 6 meters); or by a longer detour via the Strait of Malacca, often used by vessels coming from India or unable to cross the Sunda.

After four to five months in the harbor of Canton, ships would set sail between late December and early January due to the northeast monsoon, blowing from the mainland between December and April, thus crossing the Cape of Good Hope before the bad season, i.e. before May. The vessels would then be carried by the South-West trade winds, sometimes stopping on the islands of Saint Helena or more often Ascension, where the presence of numerous sea turtles made it possible to prepare restorative broths for the sick. Past the equator, the route bypassed the Azores to the West, with ships then entering an area of the prevailing westerly winds which made it easier to approach the European coasts. Arrival was generally between August and September, after 20 to 22 months of travel, of which two-thirds were at sea (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 61-75; Croix A.-Desroches J.- P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, pp. 31-33; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 86-95).

Imports of the Compagnie française des Indes

Fabric, spices, tea, coffee

The Compagnie des Indes made its greatest profits on fabric (cotton from India, silks from China), spices, tea, and coffee (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 77-87; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 287-306, Croix A.-Desroches J.-P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, pp. 40-43, 52-53, 102-103; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 203-211, 228-233). Although a minority among shipments, works of art, porcelain, lacquer, and wallpaper were also successful (Estienne R., 2013, p. 222-227).

Porcelain

The Compagnie des Indes did not import any porcelain before 1680 despite having access to Asia, with the exception of 656 Persian porcelains brought back in 1672 (AM Lyon, HH 323). They had been bought either in India, probably in Surat, the nearest port to Persia, or directly at the Persian comptoir of Banderabassy (now Bandar Abbâs). The purchase contract was not renewed due to the fact that porcelain connoisseurs had little regard for Persian porcelain which they deemed incomparable with the Chinese.

Far East porcelain imports did not begin until 1680 with the small shipment of 5,520 pieces. In the following year, the cargo was comprised of 15,000 pieces. In 1682 the ships returned with 55,465 pieces of porcelain, then 153,000 in 1683, and only 133,900 in 1684. In total, the company imported only 363,541 pieces of porcelain between 1680 and 1685 (Castelluccio St., 2007; Castelluccio St., 2013, p. 22).

Blue and white decorated porcelain probably made up the majority of these shipments, due to the inventories rarely listing decor, with the exception of the dishes, cups, plates, and pots brought back in 1682 called “de couleurs figurez”, probably decorated with green enamels.

The spectacular growth in import volumes overshadowed three major strategic errors:

- the almost total lack of variety in the shipments, which only included houseware pieces and no decorative ones.

- too much of the same type of objects. Thus, during these five years, the imported porcelain was comprised 86% cups, 13% plates, and 1.6% dishes and as many pots.

- the poor choice of porcelain, to the point that in a letter dated March 11, 1684, the directors criticized the clerks of the Surat comptoir for sending “300,000 sparrow cups, which where useless due to their small size. And when they would have been bigger, there were too many to be sold” (AN, col/C/2/5, f° 84; AM Lyon, HH 323). On the one hand, the cups were too small to be able to consume any hot drink, while on the other hand, their large quantity led to a drop in prices.

Finally the new Compagnie des Indes gave up porcelain importing in the beginning of 1685 with the establishment of a new board. From then on, import trade was carried out by individuals or private compagnies or from the spoils of war.

New porcelain did not arrive until September 1688, with 13,408 pieces sent by Constance Phaulkon, Prime Minister of King Phra Naraï of Siam. Its sale in the following October paid a part of the Minister's stake in the capital of the company (AN, col/C/1/26, f° 7). Phaulkon had taken care to vary the shapes and decorations of the pieces with a majority of blues and whites, as well those with polychrome decoration probably being famille verte porcelain. The shipment from Phaulkon differed however from the Compagnie des Indes imports by including much porcelain decorated with colours and a wide choice of decorative vases including 73 urns and 1,004 vases (AN, col/C/1 /26, f° 39-42, 89-94).

In 1695, two English vessels were seized, the Prince of Denmark and the Seymour, containing porcelain that was sold in May-June 1696, without a detailed cargo list. The 1696 seizure of the Defense, the Succez and the Resolution by the English East India Company, generated an auction of 72,316 pieces of porcelain in September (Mercure galant, January 1696, p. 154-155). As in the French company’s cargoes, the majority were housewares, yet for the first time, "pagodas" were presented for sale. These were highly appreciated for their originality and decorative aspects including human figurines, generally in a standing pose, as well as statues of lions, dogs, peacocks, cats, roosters, and "30 diverse small figurines". The success of the auction was mediocre, probably due to the large amount of housewares.

It is impossible to know whether any porcelain was sold before the return of the Compagnie de la Chine’s Amphitrite ship in 1700 due to the absence of cargo lists from 1697-1699. The brief cargo list for the vessel did not specify the quantity of pieces nor the nature of their decorations. The porcelain did include traditional housewares, such as bowls, basins, saucers, dishes, plates, tea pots, goblets, cups, sugar bowls, or salt shakers. New products such as ewers, bottles and above all “mantle ornaments, modes et modèles, and other works” were offered for sale (AN, col/C/1/17, f° 17-17 v°. Mercure galant, September 1700 , p. 212).

None of the existing texts list the details of the last two porcelain sales of the reign of Louis XIV which took place in October 1703 and in September 1715, after the Amphitrite’s second trip from China (Mercure galant, August 1703, p. 327- 329. AM Nantes, HH 201.46). There were apparently only three porcelain auctions in France between 1700 and 1715, all of which were by made by Compagnies privées de la Chine et de la Mer du Sud.

Between 1732 and 1747, the Compagnie Française des Indes Orientales brought back between 123,000 and 868,000 pieces of porcelain per year. However, commercial interest declined throughout the century. Their purchase price in China increased regularly while in Europe the selling price decreased. In addition, their quality was considered increasingly mediocre facing strong competition from European porcelain (Dermigny L., 1964, I, p. 390-391; Mézin L., 2002; Shimizu C .-Chabanne L., 2003; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, p. 297; Croix A.-Desroches J.-P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, p. 40; Estienne R. ., 2013, pp. 234-239; Castelluccio St., 2013, pp. 114).

The shipments consisted mainly of items intended for dining purposes, with complete dining services (AN, col/C/2/23, f° 109; C/2/24, f° 50; C/2 /29, f° 87-87 v°; C/2/49, f° 87-87 v°. Dermigny L., 1964, I, p. 390; Constant Ch de., 1964, p. 329; Castelluccio St ., 2013, pp. 114, 124-127). Ornamental vases receive little mention, either because the company did not import them systematically, or their quantity was too negligible to garner sufficient commercial interest and gain notice, or the imported pieces met market expectations and no comment was necessary.

Lacquers

The Compagnie des Indes Orientales imported very few lacquer in the 17th century, with only two cabinets and two screens from Japan in 1670 (AM Lyon, HH 323), two screens from China in 1687 (Mercure galant, Septembre 1687, p. 81 ), and a cabinet the following year with unspecified provenance (Mercure galant, September 1688, p. 96; Castelluccio St., 2007, p. 122-123; Castelluccio St., 2014, p. 304 ).

This almost negligible quantity of seven pieces in eighteen years testifies to the company's lack of interest in lacquer, the supply of which was limited and the profit margin unattractive, contrary to fabric and spices.

Despite this, the Amphitrite returnedfrom Canton in 1700 with eighteen screens, eleven cabinets, 272 cassettes, fourteen cases of cabarets and shaving bowls as well as a writing desk in gold leaf, all of which were Chinese lacquer (AN, col., C1 17, f° 17-17 v°. Mercure galant, September 1700, p. 210-211).

Returning from a second trip in August 1703, the Amphitrite brought back 78 screens from China, two others from Japan, 45 cabinets, 521 boxes from China, and 2,110 cabarets (Mercure galant, August 1703, p. 327- 329; Castelluccio St., 2007, pp. 123-124).

Even if the quantities and the diversity of the pieces was nothing compared to the imports of the Compagnie des Indes in the 1670s and 1680s, the choice remained rather classic with less than 7% of screens, cabinets and chests, and a very large majority of trays, boxes and other small objects. In 1700, about two thirds of the lacquer were Chinese and one third Japanese. These proportions were justified by the ease of acquiring local productions and by the high cost of Japanese creations.

The surviving lists confirm the diminishing diversity in the shipments concerning lacquer throughout the 18th century. They no longer mention any chests, while two to three cabinets, essentially Chinese, only appear between 1716 and 1723. Two to six screens, very likely originating in China, were mentioned in 1722, 1726, and from 1735 to 1740 , then they too disappeared (AM Nantes, HH 202.11, 16; HH 221.56, 69; AN, col/C/1/10, f° 107; C/1/11, f° 79; C/2/23, f ° 109; C/2/24, f° 50; C/2/25, f° 218; C/2/27, f° 102; C/2/28, f° 123; C/2/29, f ° 73v°, 74, 129; C/2/49, f° 87, 142; C/2/52, f° 235, 258; C/2/53, f° 292 v°; C/2/53, f° 295; C/2/54, f° 103; C/2/281, f° 111. Mercure galant, September 1716, p. 259; Le Mercure, July 1722, p. 174; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 294, 392-393, 418, 631).

The 1727 sale in Nantes appears to be the last to still offer a certain variety of lacquer, all from China, including nine screens, forty "commodes de vernis", eight "bureaux idem" and twenty-four "different lacquered caisses from China". (SHD Lorient, 1 P 308.78.42). These commodes were not woodwork pieces, but "boxes designed for a type of mounted coiffure which they [women] would put on like men put on their wigs". (Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, 1740, art. “Commode”). The "bureaux" had a "small desk covered with green cloth in front of one as if for writing" while those brought back from Asia had a fully lacquered flap (Furetière A., 1690, art. “Bureau”, “Escritoire”). The legend of sending furniture from Europe to have it lacquered in the Orient stems from a misunderstanding of the term "bureaux" and "commodes", because no written record confirms the shipment from Europe of furniture destined to be lacquered in Asia.

According to the shipping lists, trays or “cabarets” were the only lacquer imported by the company as of 1741, which rarely number less than a thousand pieces. While the company's agents could have acquired a greater variety of Chinese lacquers in China as well as Japanese ones brought back by Chinese merchants, they took no risk in limiting themselves to a steady import of cabarets. The goal to attain a maximum amount of profits probably explains the Compagnie’s director’s decision to focus on this type of merchandise.

Wallpaper

In the 17th century, the various European compagnies in the Indies occasionally exported Chinese wallpaper from their Indian offices. In the 18th century, wallpaper was sold in Canton either in sheets or mis en oeuvre primarily as screens or fans.

Most of the exports were in the form of feuilles about 80 centimeters wide and lengths varying between 1.45 and 1.75 meters, reaching 1.94 meters (Duvaux, 1873, II, p. 231, no. 2040; Castelluccio St., 2018, pp. 8-9). In order to prevent accidents during the crossing, the sheets were packaged either in rolls or in packs of ten sheets, probably shipped in boxes (AN, col/C/1/17, f° 17 v°; O1 *3445 , f° 107; O1 *3341, f° 299 v°-300, no 385-396; SHD Lorient, 1 P 258A.111.48. Mercure galant, September 1700, pp. 209-210; Constant Ch. de, 1964, pp. 262, 264, 302; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, p. 294, note 231).

In the 1730s and 1740s, annual imports of Chinese wallpaper fluctuated between 600 and 1,200 sheets. From 1750 to 1773, the volumes rose to 3,600 sheets, which remains modest compared to the tens of thousands of porcelains brought back by the ships (AN, col/C/1/11, f° 79; C/1/17 , f° 17; C/2/24, f° 5; C/2/25, f° 218; C/2/28, f° 115 v°; C/2/29, f° 129; C/2 /52, f° 258; C/2/53, f° 295; C/2/54, f° 103; C/2/281, f° 65, 243; SHD Lorient, 1 P 305.70.150. Mercure galant, September 1700, pp. 209-210; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, p. 294, note 231; Castelluccio St., 2013, p. 114).

Screens rarely appear in cargo, possibly due to their size and fragility. In the 18th century, only two screens seem to have been brought, in 1772 (SHD Lorient, 1 P 260.27.129).

Paper fans belonged to those small import objects of reduced bulk and cost and guaranteed sale. As for the wallpaper, these fans were made in advance and the agents of the various Indian compagnies bought them in the shops of Canton, which saved them precious time. No figure is given for these fans, probably imported by the hundreds.

Cargo sales

The vessels returned during the summer and the sale of their cargoes took place during the following months of September and October. The directors of the Compagnie des Indes took over the principle of auctions from the Dutch East India Company, in four successive locations:

The first sales took place from 1669 to 1673 in Le Havre, a commercial city easily accessible from Paris, in order to attract the greatest number of merchants from the capital.

Due to the Dutch War, the English Channel became less secure, as the Dutch fleet cruised there, so the cargo of the Soleil d'Orient was sold at La Rochelle in 1674 to prevent its capture by enemy vessels. However, due to the lack of bidders due to the distance from La Rochelle, the sale was mediocre and some of the goods remained in store.

The sales then took place in Rouen, from 1676 to 1688, a merchant port even closer to the capital than Le Havre. The success of the sales confirmed the relevance of the choice of Rouen for their development, a city chosen by the company throughout the period of peace which lasted until 1689, the beginning of the Augsburg league.

Always to avoid the Channel where the English and Dutch enemy fleets crossed, the sales moved to Nantes from 1689 to 1734. Then, to limit the transhipment of goods from Lorient to Nantes, from 1735 and until the Revolution, the sales were now held in Lorient, the company's home base since its creation (Sottas J., 1994, p. 396; Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 77-87; Haudrère Ph., 2005 , I, pp. 307-312).

Sales preparation

As one of the members of the Compagnie des Indes noted, "only competition from merchants maintains prices", so the directors had every interest in giving the greatest impact to these public sales. From 1669, the Gazette and then the Mercure galant, both controlled by the royal powers, announced the arrival of the ships of the Compagnie des Indes fairly regularly, with a delay varying from three to fifteen days after their arrival.

From August 1684, the Mercure galante irregularly published lists of shipments, copied verbatim (AN, col/C/1/17, f° 17-17 v°. Mercure galant, August 1684, p. 81-83; September 1687, pp. 77-81; September 1688, pp. 91-96; October 1695, pp. 318-324; November 1695, pp. 182-191; September 1696, pp. 186-191; September 1700, p. 205-213; September 1701, pp. 303-310; August 1703, pp. 327-329). This distribution, launched in 1684 by the directors of a company on the edge of ruin, testified to their desire to make the dates and content of the sales known to as many people as possible in order to attract as many buyers as possible. In the 18th century, the Mercure de France published the names of ships arriving safely, but no longer lists of cargoes, which appeared instead in specialized journals such as the Gazette du Commerce.

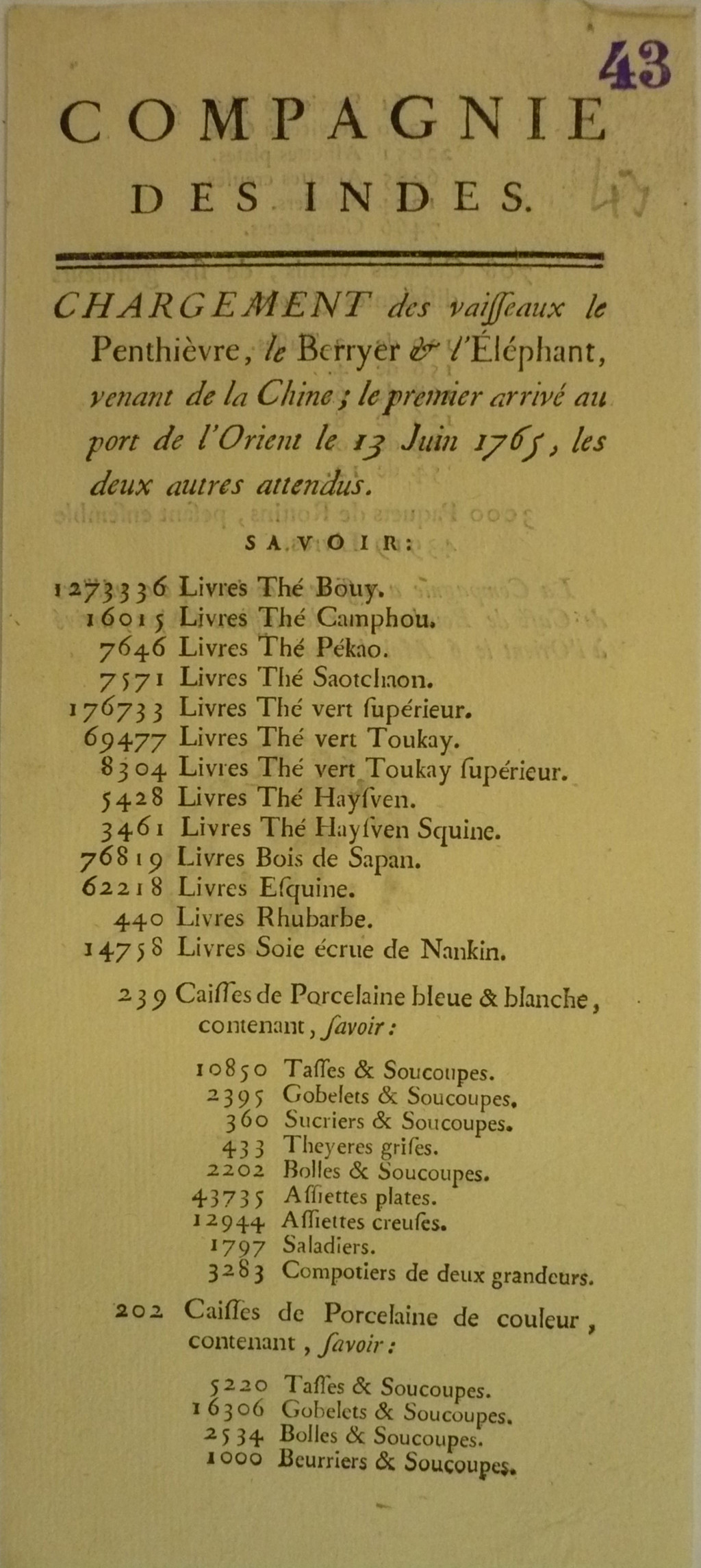

The publication of lists describing succinctly the contents of the cargoes one to three weeks after the arrival of the ships, according to Dutch practice, was the next step. These lists, aimed at merchants and other potential buyers, included all the practical information necessary to prepare their trips and purchases: the names of the vessels, their date of arrival in Lorient, the place and days of the sales, as well as the period of time during which the goods would be displayed before the auction. These lapidary lists began with fabrics and continued with spices and other miscellaneous goods, with lacquerware and porcelain bringing up the rear.

At the same time, “the time of this sale is notified to merchants and traders by posters that are affixed in public places in the main cities of the kingdom” (Savary des Bruslons, 1723-1730, art. “Toile”). Delays in the opening of sales were also brought to the attention of merchants and traders by means of posters (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 87-93; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, p. 307).

Auctions

While in Le Havre and Rouen the text did not indicate the location of the sales, in Nantes, they were held “in the Hôtel de la Bourse”. After their final transfer to Lorient, an auction room was built in a pavilion, which still exists.

A few days before the sale, a representative sample of the contents of each type of goods was taken from the boxes and presented to potential buyers, so that they could judge their quality and condition and select those of interest. In the early 1670s, this presentation lasted eight days, reduced to six in 1676 and then three in the early 1680s (AM Lyon, HH 313, 323).

Sales were made from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. and lasted several days, until the shipments were exhausted, always in the presence of two to three directors from Paris (AN, col/C/1/24, f 91; C/2/6, f° 170; Municipal Arch. Lyon, HH 313, f° 125, 162 and HH 318, September 27, 1684. Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 87- 93; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 307-308; Croix A.-Desroches J.-P.-Guillet B.-Rey M.-C., 2010, pp. 56-57; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 240-249).

Buyers and transport in paris

Merchants from Nantes and Lorient constituted the majority of buyers, some buying for Parisian colleagues, who were rarely present due to the distance and the cost of travel and accommodation (Haudrère Ph.-Le Bouëdec G., 1999, p. 87-93; Haudrère Ph., 2005, I, pp. 308-327; Estienne R., 2013, pp. 240-249).

From Nantes, the goods were transported by boat, therefore at a lower cost, to Orléans by the Loire, then transferred to carts for transport to Paris.

From 1735, land transporters, or rouliers, ensured the transport of goods from Lorient to Paris by road. Transporters by water or by land were responsible for the delivery time and the condition of the goods upon arrival, except for exceptional accidents (SHD Lorient, 1 P 284A.105.1; 1 P 284A.111.21 and 22; 1 P 288A.175.29 and 53 Savary des Bruslons J., 1723-1730, art. “Roulier”, “Voiture”, & “Voiturier”). Departure days depended on the roulier, who was probably waiting for his vehicle to be full. It was also possible to send the goods by courier on fixed departure days, but the cost was then multiplied by five.

In Paris, the retail sale of porcelain, lacquerware, and wallpaper fell under the jurisdiction of the guilds of marchands-merciers and faïenciers for the former.

Conclusion

The trade with the Indies and China that developed in the 17th century foreshadowed the great international trade to come. The Compagnies des Indes orientales ensured the bulk of these exchanges and constituted a great adventure at once political, economic, technical, geographical, and social. They were the first companies with shareholders; their monopoly made it possible to pull together the very large necessary funds that a simple individual could not provide, in order to concentrate capital, energy and skills; regular rotations and imported volumes increased throughout the century, an evolution that contrasted with the one-off shipments of the 16th century. The Compagnie Française des Indes orientales was eminently political, as the will of Louis XIV and Colbert and the share of the State remained significant. This state presence explains the lack of flexibility of the administration of the company and its difficulty in adapting to changing commercial, strategic, and political conditions in the second half of the 18th century (Haudrère Ph., 2005, II, p. 819-825).

Among the various products it imported, the fabrics, porcelains, lacquer, and wallpapers had a profound influence on European taste and art, from perspectives both aesthetic and technical. Oriental porcelain stimulated research in manufactories for earthenware, then soft porcelain, in attempts to imitate it and discover the technique of true hard porcelain, which became feasible with the discoveries of kaolin deposits in Meissen in 1709, then in Saint-Yriex, near Limoges, in 1769. Lacquers were at the origin of the vernis Martin technique, while Chinese wallpaper encouraged manufacturers to go beyond domino paper. Research on wallpaper in Paris in the second half of the 18th century led to the development of major manufactories at the end of the 18th century, one of the most famous of which was in Réveillon. National production gradually supplanted Chinese imports, which regained a certain vogue in the second half of the 19th century.

Aesthetic research transcended technique and there was a transference in appearances: the blue and white decorations of the porcelain and furniture of Trianon reflected the polychromy in porcelain so fashionable at the time; at the same time, the vernis Martin furniture imitated lacquer while using the principle of the blue and white decoration of porcelain; while at Sèvres certain decorations in porcelain imitated lacquer, and others marquetry wallpaper. This manufactory also participated in the development of the preference for light colours in the 18th century and imitation by the large porcelain manufactories.

Oriental motifs also offered a source for a new ornamental vocabulary, freely taken up and adapted by European artists. They widened the field of creation towards more freedom, fancy, and bemused curiosity regarding this elsewhere, which was endlessly fascinating, as well as the stuff of fantasy.

Related articles

Personne / collectivité