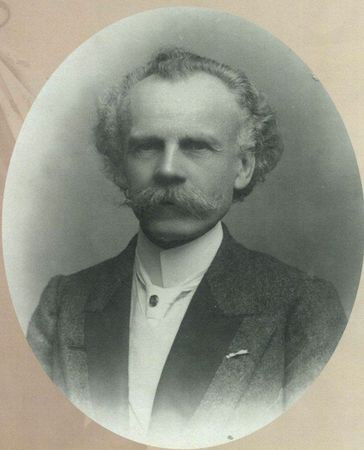

LECLÈRE Adhémard (EN)

Biographical Article

A major figure in the field of practical orientalism, whose writings are still consulted by specialists in Khmer studies, Adhémard Leclère remains unknown in his native town, Alençon. However, a room in the museum of the prefecture of the Orne still houses many unusual objects that he collected throughout his life in Cambodia. His documentary collection comprising his invaluable writings, as well as many Cambodian manuscripts, is also held in the municipal library.

Adhémard Leclère’s personal history may be understood through the lens of the labour movement. Born in 1853 into a Norman family that was partly associated with farming and supported the French republic, Adhémard went to Paris in 1874 to work in the printing works as a typographic worker. Here, he became familiar with the labour movement, became a journalist for various publications, and eventually advocated his progressive ideas in the paper Le Prolétaire, which had become the official body of the Parti Ouvrier. He became editorial secretary in 1879, and represented at the time an anti-Marxist movement known as ‘Possibiliste’, led by Paul Brousse, which acted as a transmission belt for the German socialist movement (Candar, G. and Ducange, J.-N., 2010, pp. 171–204). When the Fédération des Travailleurs Socialistes de France was established in 1883, he became the head of the Fédération Algérienne and advocated the extension of socialism to the colonies. But, as he was working at the same time for La Justice, Clemenceau’s daily paper, and apparently tired of the internal struggles within the labour movement, Leclère rallied to the latter, who soon enrolled him into his electoral campaign to become a member of parliament for the Var region, in 1885. Thanks to his support, Leclère managed to be appointed to the colonial administration, which transferred him to Cambodia in 1886. Arriving after an uprising provoked by the Republicans’ terrible management of the kingdom, he spent his entire career there—a whole quarter of a century.

As he abandoned the workers’ cause to advocate a bourgeois radical socialism transplanted to the tropics, his focus shifted from workers towards the Khmer peasantry and, more generally, Cambodian society. Considered backward, it needed to be studied in depth to assess the extent of the measures to be implemented to reform it in the ‘wake of the ‘civilising mission’ of the Republic. There was a militant aspect to the many texts he rapidly published and which addressed the religion, literary traditions, mores, and customs of the Khmers, both with regard to the lower classes and more highborn persons. But, at the same time, the was a clear desire for social recognition, as this scholarly writing was also intended to integrate him into the world of orientalist specialists and the learned circles of the metropolis, and, in doing so, make him part of the bourgeoisie. Republican messianism, the ethnographic practice of writing, and the process of embourgeoisement were linked in Leclère with a dialectical tension that pushed him towards the upper echelons of society, although he did not succeed as well as he hoped. Looked down on by academic orientalists due to his lack of rigour (Cœdès, G., 1914, pp. 45–54) and employed successively in the posts of Provincial Resident without managing to go beyond the rank of Resident Mayor of Phnom Penh, hence failing to attain the rank of Superior Resident—the colonial authority in charge of Cambodia in its entirety—, his many applications for the Légion d’Honneur were systematically rejected (AN (French national archives) OM, RSC, 255.59). He was also poorly received in his native town, after an unsuccessful attempt to run as a candidate in the parliamentary elections, which resulted in his withdrawal due to a lack of support from his own side (1902) (AD 61, M544 Alençon police station. Report. 3 April 1902); he ended up retiring in 1910. He became more interested in writing about the municipality of Alençon than about Cambodia (Leclère, A., 1914) (Leclère, A., Les Œuvres de Charité à Alençon sous l’Ancien Régime, 1914; Histoire des cimetières. La place de la Madeleine et le champ de foire, 1914; Histoire des deux halles. La halle aux toiles. La halle aux blés, 1914; La Commune d’Alençon. Histoire de son Administration municipale de Louis XI à la Révolution, 1914; La Révolution à Alençon. Année 1790, 1914; ‘L’Aliénation des Terrains du Parc d’Alençon. La création des promenades et des Rues de 1775 à 1795’, BSHAO, 1916; L’Aliénation des Terrains du Parc d’Alençon. La création des promenades et des Rues de 1775 à 1795, 1916); he found it difficult to be accepted by the local officials and their learned society, the Société Historique et Archéologique de l’Orne, for whom his mannerisms were those of a parvenu (‘Session of 18 April 1917’, BSHAO, Vol. XXXVI, 1917, pp. 427–428). He died in Alençon on 16 March 1917.

While his works on Alençon were barely considered worthy of interest by specialists in local history, and his name was soon forgotten, the same did not apply in the microcosm of Khmer studies, within which his Cambodian oeuvre began to be studied in the mid 1950s (Porée-Maspero, E., 1955, p. 364; Bitard, P., 1957, pp. 563–579). The latter was indeed able to grasp the richness of the Leclère paradox: driven by Republican messianism, whose vocation was to combat the archaic aspects of Cambodian society, the colonial administrator went to great lengths to acknowledge its traditions; by observing them in vivo before they were swept away by the various manifestations of an aggressive modernity, he managed to save whole sections of them. The source of this paradox may lie in his rural ancestry: studying the popular rites of passage of the Khmer country probably reminded him of the superstitious, enchanted, and conservative world of his grandmothers in the Mayenne region of France (Fonds Adhémard Leclère (FAL), MS 703/4, ‘Souvenir d’enfance’ (‘childhood memories’), 9 ff.), from which the Republican education system had snatched him at an early age. His paternal grandmother, a midwife and something of a ‘witch through her ancestors’ (sic), was, in fact, a royalist, while his maternal grandmother, a farmer, was related to several local families of squires.

In any case, Leclère’s oeuvre has not yet yielded all its virtues: aside from the many Cambodian documents that remain to be studied, his collection of manuscripts contain several previously unpublished works, and, in particular, romans à clef (novels about real life) that described colonial life in the Cambodia of the Protectorate (seeinter alia: Le Résident Verrier (FAL, MS 701/2; 701/3-d), which would be worthy of publication. There are several grey areas in his biography, both with regard to his supporters (or his adversaries) within the colonial administrative system, and the Cambodian teams, networks, and factions with which he was in contact; it was through these channels that he obtained first-hand (documentary and ritual) information.

The collection

Held in the Médiathèque in Alençon, Adhémard Leclère’s collection of manuscripts, which has been entirely scanned, can be consulted online: https://bibliotheque-numerique-patrimoniale.cu-alencon.fr/Fonds-Adhemard-Leclere, together with the inventory of the collection and its detailed description (readers can consult the inventory and description, both extracted from Mikaelian, Grégory, Un partageux au Cambodge: Biographie d’Adhémard Leclère suivie de l’inventaire du Fonds Adhémard Leclère, Cahiers de Péninsule, 2011, Issue 12, pp. 173–457). In short, there are a total 17,000 sheets comprising several of Leclère’s previously unseen texts, some of which contain important information about the history of Khmer society during colonial rule, as well as, and above all, Cambodian documents of great importance—traditional narrative manuscripts and documents relating to administrative and royal practices—, whose study will be necessary in order to improve our knowledge of the history of Cambodia during the modern and contemporary eras.

Held in the Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle in Alençon, and placed in part in a room that has been specifically allocated to them since 1982, the objects brought back by Adhémard Leclère have not yet been precisely identified. The collection is nonetheless one of the richest collections of Cambodian objects (as well as, more generally, Indochinese objects) held in French museums. They attest to the daily and ceremonial lives of the Khmer people, its monastic and palatial elites, as well as the lives of the highland peoples who lived on the high plateaux isolated from the Khmer royalty or those of the urban underworld. Hence, there were 800 objects ranging from hunting trophies to coins, medals, seals, weapons, wickerwork, musical instruments, jewellery, clothing, theatre headdresses, religious supports, mouldings of Angkorian sculptures, post-Angkorian Buddhist statuary, drawings and watercolours, traditional manuscripts on palm-tree leaves, prehistoric artefacts, and almost 440 photographs, some of which are on glass plates. Four exhibitions enabled the inhabitants of Alençon and curious visitors to take a closer look at some of these objects: the first was held during Leclère’s lifetime, in 1894, and the second in 1976 (‘Le Cambodge à Alençon. Présentation des collections d’Adhémard Leclère’, 1976), the third in 1982, and the last in 2009 (‘Le Cambodge d’Adhémard Leclère et le trésor indochinois d’Alençon - (1853-1917)’, 2009).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne