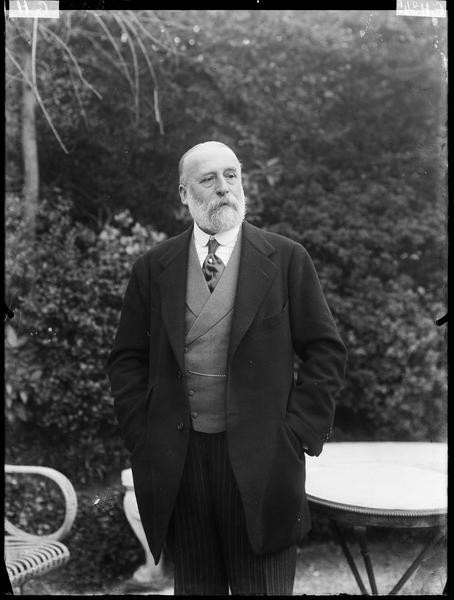

DOUCET Jacques (EN)

Biographical Article

Jacques Doucet, Couturier

Jacques Doucet was born on February 19, 1853 into a family in the fashion business: his father, Édouard Doucet, owned a men's shirt shop and his mother, Mathilde Doucet (née Gonnard) had a lace and lingerie establishment at 21, rue de la Paix in Paris ("Trente ans de mode", Vogue, March 1, 1923, p. 3-11). Doucet began working in the family business around 1875 and developed it into a fashion house. In January 1888, he left the family home to settle on his own at 27, rue de la Ville-l’Évêque.

Around 1890, Doucet received his first orders for dresses for a wealthy Parisian clientele. His name began to appear under fashion plates. In 1898, upon his father’s death, he inherited the fashion business, which he transformed into a house of haute couture (Calderini L., 2016, p. 244-246).

Doucet worked with the designer José de La Peña de Guzman and others who went on to become major fashion designers, such as Paul Poiret, Doucet's employee between 1896 and 1900, and Madeleine Vionnet, who succeeded him from 1907. He also entrusted a large part of the management of the fashion house to his friend and confidant, Charles Pardinel (Chapon F., 2006, p. 69-71).

Between 1913 and 1920 Doucet sponsored the Gazette du bon ton, a monthly publication which presented designs by Doucet as well as from other couturiers in each issue (Chapon F., 2006, p. 97, note 120).

Rue Spontini and Ancient Art

The year 1903 marked a turning point in Doucet's personal life: at this time, he conceived the project of building a hôtel particulier, the future setting for his collection, at 19, rue Spontini, in Paris. The architect was Louis Parent, in collaboration with the decorators Georges Hoentschel and Adrien Karbowsky. While completed in 1906, the mansion did not house Doucet's collection until the summer of 1907 (AP, casier sanitaire, 17-19, rue Spontini, 3589W 2104 and April 1903, ventes par la société Menier à M. Doucet, Me Fontana, notaire, AN, MC/ET/XCII).

Between 1909 and 1913, Jacques Doucet was treasurer of the Société de reproduction des dessins de maîtres, founded in Paris in 1909 and chaired by Jean Guiffrey (1870-1952): "The Society for the Reproduction of Master Drawings is a meeting of scholars and amateurs who propose the reproduction, by the most exact processes, of ancient and modern drawings, French and foreign, preserved in the public and private collections of France" (Incipit, Société de reproduction des Dessins de maîtres, unpaginated, first and second year, 1909-1910). Its headquarters were at 19, rue Spontini. In 1911, Doucet again took on the role of treasurer for the new Société française de reproduction de manuscrits à peintures, then in 1912 participated in the creation of the Société pour l’étude de la gravure française (Chapon F., 2006, pp. 192-193). During these years, he also made several trips: to Egypt in March 1909, to Naples, Greece, and Dalmatia in the spring of 1911, to Germany the same year, and again to Italy with André Suarès in 1913 (Chapon F., 2006, p. 38).

Likely due to the death of his mistress in February 1911, who had been murdered by her husband, Doucet sold his collection of ancient art in June 1912 and left his hotel on rue Spontini in December 1913 (Delatour, J., 2019).

The Library of Art and Archaeology

In parallel with the construction of his hôtel particulier on rue Spontini, Doucet began to collect documentation that eventually gave rise to an art and archeology library between 1906 and 1914. He wished to compensate for the absence of such specialised holdings in France. This opened to the public in April 1909, at 16, rue Spontini, with the art critic René-Jean (1879-1947) at its head (letter from Jean Sineux to Pierre Lelièvre, October 18, 1943; AN, AJ 16 8388, cited by Sarda M.-A., 2021).

The library kept reference publications and photographic documentation as well as numerous additional sources (archives, manuscripts, autographs, old works, sales catalogues, etc.). It also contained prints and drawings. In 1905, Doucet collaborated with contemporary artists to put together a cabinet of modern drawings and prints for the library (Debray C., 2016, p. 135). Noël Clément-Janin (1862-1947) assumed the duty of curator of modern prints on September 1, 1911 (1862-1947) [Georgel C., 2016-1]. Doucet also called upon specialists such as the orientalist Édouard Chavannes (1865-1918), who advised him on the acquisition of 200 Chinese volumes between 1909 and 1917 and from whom he acquired the photographic collections of his mission in North China and in Manchuria in 1907-1908. Doucet also purchased the photographic collections of the archaeological mission of Victor Segalen in China, in 1914, which he financed, as well as those of the mission of Paul Pelliot on the borders of China and Turkestan, between 1906 and 1910, and Victor Goloubew in Northern India in 1910-1911 (Labrusse R., 2016, p. 156).

Doucet actively supported the six exhibitions devoted to the history of Japanese prints organised by Charles Vignier between 1909 and 1914 at the Musée des Arts décoratifs: he lent prints from the collections of the art and archeology library and financed the exhibitions (Labrusse R., 2016, p. 156).

On January 1, 1918, Doucet donated the library to the Université de Paris.

Avenue du Bois and Studio Saint-James: Sponsoring Modern Art

In December 1913, Doucet moved into an apartment at 46, avenue du Bois in Paris. The furniture and decoration were the work of Iribe, the Martine workshop of Paul Poiret, Eileen Gray, Clément Rousseau, Gaston Le Bourgeois, and René and Suzanne Lalique (Possémé E., 2016, p. 116). Around the same time, he became involved with patronage, supporting artists such as Picabia, Adler, and Legrain. In 1919, at the age of 66, he married, under a marriage contract, Jeanne Roger (1861-1958), a former companion, who had come back to him in 1917 (Possémé E., 2016, p. 116, Delatour, J., 2019 et contrat de mariage de Jacques Doucet et Jeanne Roger, AN, MC/ET/XCII/1814, étude 92). After the war, Doucet modified the layout of his apartment on avenue du Bois in order to include furniture by Pierre Legrain and Marcel Coard, favouring furnishings inspired by the Cubist movement and African art (Possémé E., 2016, pp. 116 and 122).

Between 1916 and 1925, he also acquired the property of Les Nonettes, in Villers-sous-Esquery (Oise) [legs de Jacques Doucet, AN, MC/ET/XCII/1972]. He also owned a hunting lodge in Nouan-le-Fuzelier, the "château des Fontaines" (Peylhard A.-M., 2016, p. 232).

Doucet sold his couture house in 1925 and ceased his professional activity (Peylhard A.-M., 2016, p. 233). He devoted the last part of his life to a new decorative enterprise: from 1926, he commissioned the architect Paul Ruaud to modify a building annexed to the hôtel particulier owned by his wife at 33, rue Saint-James in Neuilly, where he wished to set up a "studio". The couple moved into the mansion in August 1928, but the collector died of a heart attack in October 1930, shortly after the studio’s completion (Georgel C., 2016-2).

The Literary Library

On July 2, 1914, André Suarès, whom he had met a year earlier with mutual friends, suggested to Doucet that he set up a “Montaigne-style bookshop”. The couturier took up the idea on his own two years later, in May 1916, asking Suarès to tell him the names of the authors to be sought out to enrich his library, "apart from the quartet of which it was made up" (Claudel, Gide, Jammes, Suarès, to which he added Valéry). In 1921, André Breton entered the service of Doucet (Calderini L., 2016, p. 247). André Suarès’ friend, Marie Dormoy, succeeded him in 1925 as librarian, in the premises at 2, rue de Noisiel. For thirteen years, until 1929, Doucet not only collected rare editions and precious bindings, but also everything that contributed to documenting contemporary creation: proofs, manuscripts, and correspondence. For this, he enlisted the services of writers, such as André Suarès, Pierre Reverdy, Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, Raymond Radiguet, André Breton, Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos and many others.

This library was bequeathed by Doucet to the Université de Paris upon his death in 1929 (Chapon F., 2006, p. 313-377).

The Collection

The way in which Doucet composed his collection, the chronology and modalities of his acquisitions, are not well understood. No document, contemporary address book, inventory, or list has yet been found that would enable the entries of the works to be dated and their suppliers to be identified. His correspondence has only been partially preserved and does not provide further information on this subject. However, it does seem evident that he bought in a variety of manners, including from other collectors, at public sales, from descendants of artists, and from dealers.

From Impressionism to the 18th Century

As Jacques Doucet told Félix Fénéon, he first began to collect Impressionist works in 1874 (Fénéon F., 1921, p. 313). Anne Distel notes that the “limited collection of Impressionist works put together by Jacques Doucet from 1879-1880, with Monet, Degas, Pissarro and Cassatt, complemented by Raffaëlli and Forain […] seems reserved for the private sphere of the aficionado”. These works appear only "as exceptions" in Jacques Doucet's reception rooms until 1912 (Distel A., 2016, p. 98-111). Most of them were probably resold before 1907, when Doucet moved into his house on rue Spontini. His insurer found only three modern paintings there: Le Lièvre, by Édouard Manet, which entered his collection in 1906, the Paysage d’hiver à Louvecienne by Alfred Sisley, and L’Amateur d’estampes, by Honoré Daumier. However, Doucet again bought Impressionist works as soon as he moved into his new house, including paintings by Degas in 1907 and Van Gogh in 1909 (Georgel C., 2016, p. 94 and Distel A., 2016, p. 109) .

Completed in 1906, the hotel on rue Spontini did not however house Doucet's collection until the summer of 1907 (AP, casier sanitaire, 17-19, rue Spontini, 3589W 2104 et AN, avril 1903, ventes par la société Menier à M. Doucet, Me Fontana, notaire, MC/ET/XCII). In 1905 and 1906, the collector carefully prepared his move, adjusting the composition of his collection in the process. On May 16 and 17, 1906, he organised the first dispersal of part of his collection at auction (Catalogue des tableaux anciens, pastels, dessins, aquarelles, sculptures, objets d’art et d’ameublement du xviiie siècle provenant de la collection de M. J. D…, 1906). On the occasion of this sale, Doucet obviously sifted through the works from his 18th century collection and got rid of pieces that were minor or even fake (see the derogatory annotations in the margin of the copy of the catalogue kept at the BnF, YD-1 (A, 1906- 05-16)-4).

After being thinned out in 1906, Jacques Doucet's 18th century collection increased in quality. Its paintings included a few pieces that were coveted by museums, such as the portrait of Duval de l’Epinoy by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, that of Abraham de Robais by Jean-Baptiste Perroneau, or the Projet d’aménagement de la grande galerie du Louvre et L’Incendie de l’Opéra, vu des jardins du Palais-Royal, le 8 juin 1781 by Hubert Robert. However, this collection of French paintings and drawings, clearly centred on the human figure and the portrait, was numerically small compared to the contemporary 18th collections of Camille Groult or the Marquis of Hertford (Faroult G., 2016, p. 36). Similarly, important works by Clodion, Lemoyne and Houdon are found among the sculptures, but this in no way rendered Doucet's collection of French sculpture comparable to that of Mme Arman de Cavaillet, Pierre Decourcelle, or Guillaume de Gontaut-Biron (Scherf G., 2016, p. 50).

The 1912 Sale and the Dispersal of the 18th Century Art Collection

Doucet never clearly explained the sale of his 18th century collection and his departure from the hotel particulier on rue Spontini. In 1921 he declared his change of course as a collector to Félix Fénéon: "Old things, dead things, and I prefer life to dust" (Fénéon F., 1921, p. 313-318). As early as October 1911, the Burlington Magazine informed its British readers that the sale of "eighteenth century paintings and objects" would take place the following year (R.E.D., 1911, p. 62). François Chapon and Sébastien Quéquet analysed in detail the preparation and progress of the sale, which took place from June 5 to 8, 1912 at the Georges Petit Gallery (Chapon F., 2006, p. 199-223 and Quéquet S., 2016, pp. 84-91). Published in three volumes, the catalogue is of exceptional scientific quality. The scientific work of promoting the collection as well as the publicity organised around the sale allow the total amount of the auctions to reach a total amount of 13,884,460 francs, which exceeds the sales records of previous years (Quéquet S., 2016, pp. 85-86).

Charles Vignier and the Asian Art Collection

Alongside this ensemble, dominated by 18th-century French art, Doucet had built at least a small collection of Asian art since the 1890s, which he presented with his 18th-century collection and which, between 1906 and 1912, he decided to systematically enrich with the help of the dealer Charles Vignier. "Do you believe that I have a chance, although late in starting a collection of objects from the Orient and the Far East, of placing myself among the main connoisseurs in this exercise?” the collector asked. During the sale of this collection, Charles Vignier prided himself that “without a single exception, all [Oriental and Far Eastern] objects were purchased from me […]. From the time of the war, Jacques Doucet ceased his business relations with me and did not thereafter resume them" (introduction by Charles Vignier to the Catalogue Jacques Doucet. Céramiques d’Extrême-Orient, bronzes, sculptures, peintures chinoises et japonaises, laques du Japon, faïences de la Perse, de la Transcaspie et de la Mésopotamie, miniatures persanesParis, 1930, unpaginated). Doucet parted with a large 17th-century Chinese screen in Coromandel lacquer, Chinese porcelain, and also Chinese and Japanese ceramics, mounted in bronze in France in the 18th century, which adorned the grand salon of the hôtel particulier on rue Spontini from the 1912 sale (lot no. 399; lots no. 196 to 205; 208 to 217). On the other hand, until his death his collection included Chinese, Korean and Japanese ceramics (lots no. 1 to 13 from the 1930 sale), Chinese bronzes (lots no. 14 to 18), three Chinese sculptures and a Persian sculpture (lots no. 19 to 22), Chinese and Japanese paintings (lots 23 to 29), a set of Japanese lacquer objects (lots 30 to 65), and 30 ceramics from Rhages, Sultanab, and Rakka (lots 66 to 96), as well as some Persian miniatures (lots no. 97 to 102).

In May 1925, he lent 75 works to the great exhibition of oriental art organised by Charles Vignier at the Chambre Syndicale de la Curiosity et des Beaux-Arts, rue la Ville-l'Évêque (Catalogue de l’Exposition d’Art oriental : Chine, Japon, Perse : organisée au profit de la Société de Charité maternelle dans les salles de la Chambre syndicale de la Curiosité et des Beaux-Arts, du 4 au 31 mai 1925, no. 52 to 127). As Rémi Labrusse noted when comparing Doucet's loans to exhibitions and the 102 issues of the 1930 sale, it is demonstrable that Charles Vignier's sales to Doucet constitute almost the entire collection of the latter’s non-Western art, with the exception of African works (Labrusse R., 2016, p. 161).

Jacques Doucet's collections of Asian art were spared by the successive sales of the collector, who held on to them while moving from between residences and continued to add to them until the First World War. On Avenue du Bois, the visitor was welcomed from the vestibule by "archaic Chinese paintings alternating with display cases where Persian ceramics shone with precious reflections" (Joubin A., 1930-2, p. 74), while in rue Saint-James, a large sculpture of a Chinese Buddha from the Sui dynasty (581-618) was placed at the top of the staircase (see the photograph reproduced in Joubin A., 1930-1, p. 17).

These collections were not sold until November 1930, after Doucet's death (Catalogue Jacques Doucet. Céramiques d’Extrême-Orient, bronzes, sculptures, peintures chinoises et japonaises, laques du Japon, faïences de la Perse, de la Transcaspie et de la Mésopotamie, miniatures persanes, Paris, 1930).

Conquering Modern Art

In 1913, Jacques Doucet's collection evolved in a new direction with his move to Avenue du Bois. Évelyne Possémé noted that in 1925, in this apartment, "works by Sisley, Manet, Soutine, Cézanne, and Van Gogh cohabitate with works by Picasso, Braque, Derain, and Modigliani" (Possémé É., 2016, p. 116).

In his interiors, Jacques Doucet now also presented Islamic art, which he had already possessed in 1910, having lent them to the exhibition of "Muslim Arts" in Munich (paintings, Persian and Syrian ceramics of the 12th-13th centuries, plates 25, 27, 94, 103 of the commemorative catalogue published in 1911 by Marcel Montandon, quoted by Labrusse R., 2016, p. 158). In 1910 he had acquired the portrait of a late 15th century painter from Charles Vignier (probably reign of Mehmet II [1444-1481], gouache and gold on paper, H. 18.9; W. 12.8 cm , Washington D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, inv. F. 1932.28). On Avenue du Bois, these works stood alongside engraved crystal doors by Lalique, a piece of furniture by Paul Iribe, and a sculpture by Joseph Bernard (photographie du vestibule de l’avenue du bois, Inha, Archives 97/3/3/19). Doucet also enriched his collection of non-Western art with a few African masks that he had bought from the dealer Paul Guillaume in 1916 (Labrusse R., 2016, p. 159 and Peylhard, A.-M., 2016, p. 170) .

His librarian, René-Jean, was the first to recommend to him the artists who exhibited at the new Salon d'Automne, inaugurated in 1913: Desvallières, René Piot, Georges Rouault, Albert Marquet, as well as Henri Matisse. Doucet’s purchases of Cubist and then Surrealist works benefited from the counsel of André Suarès, Pierre Reverdy from 1916, then André Breton, from 1921 (Debray C., 2016, p. 132-135). Doucet's first acquisition at Breton's initiative, in May 1922, was La Charmeuse de serpents by Douanier Rousseau, obtained from Robert Delaunay under the condition of a bequest to the Louvre upon his death (Debray C., 2016, p. 145) . After the war, Doucet's collection included works by Matisse, including Poissons rouges et Palette (1914, acquired in 1921, New York, Museum of Modern Art, inv. 507-1964), paintings by Marie Laurencin, works by Modigliani, Picabia, Braque, Miro, André Masson, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, a preparatory glass for Marcel Duchamp's Grand Verre, the Glissière contenant un moulin en eau en métaux voisins (Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv.19502-134-68), a woman's head by Csakt in polychrome stone from 1923, a bronze by Zadkine, La Lionne, a gilt-leaf plaster by Laurens, La Jeune Fille à l’oiseau de Miklos, as well as two major bronzes by Brancusi, Danaïde (purchased in March 1921, Tate Collection, inv. T00296) and his Muse endormie II (Debray C., 2016, p. 132-151). Doucet’s acquisition in 1923 of Picasso's masterpiece Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907, New York, Museum of Modern Art, inv. 333.1939), on the advice of André Breton, was undoubtedly his most significant coup (Georgel C., 2016, p. 152).

Epilogue: the Collection after Jacques Doucet

Following Jacques Doucet’s death, his widow and universal legatee, Jeanne Doucet née Roger, bequeathed two sculptures to the Louvre Museum, according to her husband's will and subject to usufruct: a lion's head (Sassanian Persia, fifth-seventh centuries) and a marble Buddha from the Sui period. A few paintings were donated to the French State or museums, such as LaCharmeuse de serpents by Douanier Rousseau or Idylle by Picabia to the Musée de Grenoble (Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 1937-7 and Musée de Grenoble, inv. MG 2627). The architect Paul Ruaud inherited the Nonettes property, in Villers-sous-Esquery (Oise) (testament olographe et legs de Jacques Doucet, AN, MC/ET/XCII/1972). Doucet's widow also parted with a large part of the Asian art collections at an auction presided over by the collector's expert and former dealer, Charles Vignier, on 28 November 1930 (Catalogue Jacques Doucet. Céramiques d’Extrême-Orient, bronzes, sculptures, peintures chinoises et japonaises, laques du Japon, faïences de la Perse, de la Transcaspie et de la Mésopotamie, miniatures persanes, Paris, 1930). Persian miniatures and oriental earthenware drew the highest prices (Gazette Drouot, 39e année, no 124, 29 novembre 1930, p. 1). In 1937, Jeanne Doucet sold the Demoiselles d’Avignon, among other works in the collection, to the dealer Jacques Seligmann.

After the death of Jeanne Doucet in 1958, the collection was passed on to Jacques Doucet's nephew, Jean Dubrujeaud (1880-1969). He in turn bequeathed part of his collection to the daughters of his wife's first marriage and the other part to his son, Jean Angladon-Dubrujeaud (1906-1979). His wife, Paulette Angladon-Dubrujeaud (1905-1988), founded a museum in Avignon upon her death, the Musée Angladon (Peylhard M.-A., 2016, p. 232-241). There we can now see the large Japanese painting representing Amida, Buddha of Infinite Light, from the Kamakura period, which once adorned Doucet’s living room on rue Spontini (Labrusse R., 2016, p. 156, musée Angladon, inv. 1996-M- 3).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne