LY Joseph (EN)

Biographical article

Joseph Ly, Chinese name Li Yuese (李約瑟) [Liu Q., 2017, table 34, p. 346] was born on March 23, 1803 in Mianyang (沔陽) in the province of Hubei (湖北) [Brandt J., no 81, p. 32] to farmer parents (Anonymous, 1829, p. 33), the fourth child in a family of eight.

It seems to have been by chance that during a trip to the province of Henan (河南) he visited a Catholic church and met a priest named Paul Song (Anonymous, 1829, p. 34). The latter went on to teach him the Latin language and Catholic precepts for several years before Joseph Ly entered the Lazarist seminary of Macau (act. Aomen [澳門]) on April 28, 1827. There, he continued his education with Father Louis Lamiot, Chinese name Nan Mide (南彌德)[1767-1831] – Brandt J., 1936, no 26, p. 11-12]. Originally from Bours in Pas-de-Calais, Father Lamiot had been in China since 1791; first a priest in Macao, he became an interpreter at the court of Beijing in 1794, then superior of the French Mission in 1812, and founded the seminary of the Lazarists in Macao (Brandt J., no 81, p. 32).

After a short stay at the seminary in Macao, Joseph Ly was sent to France in 1828 with three other compatriots: Jean-Baptiste Tcheng, Mathieu Lu, and François Kiou. It was there that he took his vows on July 17, 1829. During their stays, the four novices were introduced to King Charles X and the royal family, as well as to Orientalist scholars (most likely including Stanislas Julien [1797- 1873]) with whom they could converse in Chinese (Anonymous, 1829, p. 43). Before they took the seminarian’s habit, crowds of curious people would gather daily to see them and ask them questions about their country and their life in France. It was during one of these meetings that Joseph Ly expressed his astonishment at being welcomed without the slightest difficulty and so kindly by the King of France (Anonymous, 1829, p. 45). Their training at the Lazarist seminary, rue de Sèvres, should have lasted six or seven years, but it was cut short by the Lazarist superior general, Dominique Salhorgne (1829-1835), who judged the anti-religious climate of the 1830 revolution unfavourable to their stay in France (Liu Q., 2017, p. 347-348).

A work published at the time of his stay in France gives some indications of Ly’s character and his abilities (Anonymous, 1829). He is described as a sensitive being endowed with great filial piety, a rather reserved nature, speaking most of the time with lowered eyes. He is appreciated for his intellectual capacities and his great ability to express himself in Latin, a language which he is said to have learned in secret at a time when preaching in language other than Chinese was prohibited (Anonymous, 1829, p.35). His correspondence also shows his great mastery of the French language (see among others SMMN SB 52).

Joseph Ly returned to China in 1831 and was ordained a priest in Manila on April 8, 1832. He was then sent on a mission to Jiangxi in November 1833. This was interrupted at the end of 1833, when he replaced Father Jean-Baptiste Torrette (Chinese name Tao Ruohan [陶若翰] 1801-1840), then in exile in Canton, at the direction of the Macau seminary. As early as October 1833, he expressed his desire to return to the mission "to work directly in the matter of the salvation of our miserable Chinese" underlining the deep misery into which many Chinese families in Hubei had been thrown as a result deadly floods (Ly, 1833, p. 23-24). Jean-Baptiste Torrette finally gave in to Joseph Ly's "ardent desire" to return to the mission and sent him to Jiangxi in 1836 (Torrette, J.-B., 1837, p. 103). A letter recounts his perilous journey from Canton on a road strewn with thieves and dishonest porters who replaced the contents of suitcases with stones (Ly, 1837, p. 81-87). Once at his destination, he showed himself to be particularly devout, hard-working and concerned by the raging poverty in these famine-ravaged regions. He left Jiangxi (江西) to work for a few years in Zhejiang (浙江), where he stayed from 1841 to 1845.

He was then in charge of the Christians of Guangdong (廣東) as vicar general in Canton. This function hardly suited him; he encountered immense difficulties in making the faith penetrate into a province largely hostile to a foreign presence, and which considered the Christian religion to be the "sect of the fan kouey" [fangui 番鬼], a name given to foreigners and meaning "devil" (Ly, 1849, p. 203). In a letter dated 1848, he asked his superior to replace him, or at least to send him a colleague to support him in his work, preferably Chinese, because the Europeans and especially the English stirred up, according to him "a utterly relentless and inextinguishable hatred” (Ly, id.).

His protests about the Bishop of Macao resulted in being relived of his duties in 1850 (Brandt J., id.). He then returned to Jiangxi, where he had carried out most of his missions, and died on June 9, 1854.

Joseph Ly figures here as an important collector of raw materials used in the composition of Chinese porcelain and of objects that exemplify the various techniques. At a time when foreign presence was rigorously regulated, missionaries active inland were sometimes the only interlocutors providing a bridge with China.

"Instructions on how to make porcelain in China"

Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), a scholar and administrator of the Sèvres factory, had long been seeking information on porcelain manufacturing techniques in China. His various requests were unsuccessful until the Duc de Luyne (1802-1867) put him in contact with his fellow member of the Académie des Belles lettres, the sinologist Stanislas Julien (1799-1873). The latter suggested entrusting the request to the Lazarist missionaries, whom he often solicited for orders of Chinese books. This is how Joseph Ly was commissioned to bring back samples for the factory according to a list of precise instructions.

The archives of the Sèvres factory preserve a letter from Joseph Ly to its director, dated November 1st, 1844, explaining the different types of samples reported and their preparation (SMMN, 4W488). In this one, Joseph Ly makes no allusion to the context in which he collected his information and his samples (SMMN, 4W388). He mentions only at the end the price of the expenses "for the wages of those who had sought all the materials, and the pastes of porcelain and for the price of the colours", which implies that he did not carry out his mission alone. Moreover, according to the biography of Joseph van den Brandt, in 1844 Joseph Ly would have been on a mission in Zhejiang and not in Jiangxi. However, given the large amount of information collected, he very likely had to stay several times in Jingdezhen. Moreover, the letter he sent to the Sèvres factory was indeed written in Jingdezhen. It is therefore likely that during this period, and specifically for the needs of Manufacture, Joseph Ly periodically went to Jingdezhen, when he was not delegating part of the collection work to compatriots.

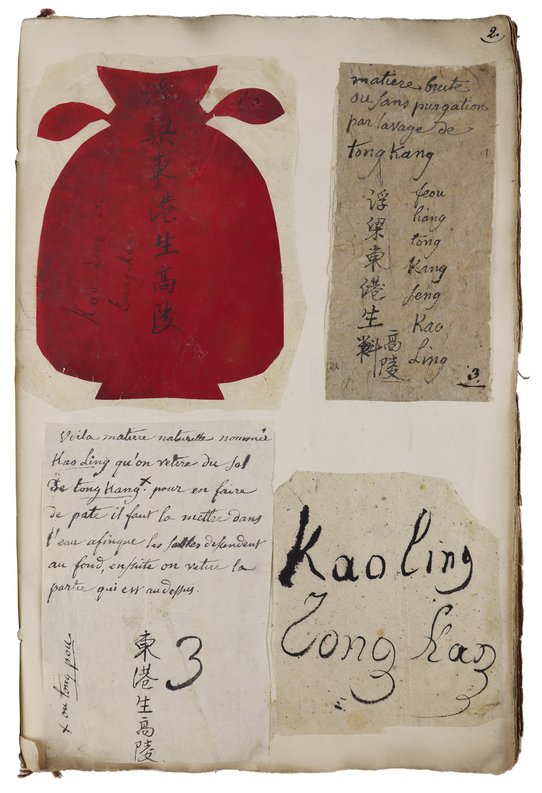

At first, the mail describes the different geographical origins of the raw materials: rocks and clay were extracted from various localities around the lake Poyang (鄱陽湖), in particular from the districts of Fuliang (浮梁縣), Qimen (祁門縣), Yugan (餘干縣), sometimes even from the neighbouring province of Hubei (湖北), to be then transported in the form of paste to Jingdezhen, where they were worked. The mixture between the different materials was crucial to obtain a sufficiently plastic paste: combining what the Chinese call the ‘flesh and bone’ of the porcelain or the porcelain stone which gives it its structure, and the kaolin clay which gives it its properties of finesse and whiteness. Joseph Ly thus distinguishes the different "recipes" of porcelain pastes, classifying them according to their qualities. Thus, "high quality” required 1 pound of paste from Yu-Kang-hien [Yuganxian (餘干縣)] mixed with 1 pound of hoa-chy [huashi (滑石)] and 1 pound of Kaoling from Sy-Kang [Xigang (西港)]”. After describing the sources of the clay, Joseph Ly moves on to the materials used in the composition of the utensils, called youguo (釉果) coming from Donggang (東港) in the Fuliang district. In addition to clays and stones, he brought back herbs called langzhi (榔芝草) which were baked with lime before being mixed with the glaze. In all, he brought back twelve raw materials, all marked with labels noting the name of the materials in Chinese and sometimes their translation. To this was added paste (which he refers to as ‘mud’) prepared according to four different compositions and small cups made using this clay.

The second part of his submissions concerns the colours used in the decoration of Chinese porcelain. He sent 24 colours of various quality, some prepared, i.e. ground with a lead powder called qianfen (鉛粉), to which were added twelve raw colours that could be used without preparation. Among these colours were also two gold leaves used to decorate porcelain. All the labels of these shipments have been preserved and compiled in the form of an album kept in the archives of the Sèvres museum, which makes it possible to systematically match the name of the old transcriptions with the corresponding Chinese characters. Some samples were wrapped in advertising flyers, including a flyer for a jewellery merchant located in Canton (d'Abrigeon P., 2022, p. 160-161). Although not specified in Joseph Ly's letter, it is likely that some of the samples related to porcelain decoration came from Canton, where enamelling workshops had been located since the first decades of the 18th century.

Joseph Ly's shipments were not limited to raw materials; he also sent the factory a selection of porcelains and ceramics. A catalogue drawn up by the curator at the time, Denis Désiré Riocreux (1791-1872), records all these objects: there are pieces classified according to their quality such as: “White teapot with long neck; the enamel and the biscuit are of 1st quality” or “Yang-Keou. [yanggou (洋狗)] Dog of Europe. Enamel and biscuit are 3rd grade” (SMMN, 4W388). These objects were entered into the inventory registers of Sèvres from numbers 3663.1 to 3663.10 and 3664.

The Samples’ Arrival at Sèvres

The boxes filled with these materials and objects were transported by boat from Canton to Bordeaux on the Cardinal de Chéverus, then from Bordeaux to Nantes on the Edith (under Captain Bardon) in January 1846. The box filled with the samples finally arrived in Sèvres in June 1846. It seems that once unpacked, the samples were immediately classified, labeled again, and exhibited in the ceramics museum. Around 1845, Stanislas Julien, aware of the great interest of these materials, asked Joseph Ly to collect several sets of samples mixing earths, pastes, glazes and colours for the École des mines, the cabinet de minéralogie of the Collège de France, as well as for his personal collection (SMMN U20 d. 19).

At the end of his letter, Joseph Ly requests compensation for the modest sum of 65 francs for the purchase of materials, and only asks his interlocutors "to have people pray for our Chinese missions, so that the Good Lord deigns save all our pagan Chinese; for which our Lord Jesus Christ shed all his blood” (d’Albis A., 2011, p. 169; SMMN, 4W388). Alexandre Brongniart seems to have acquitted himself of this debt when the pieces arrived at Sèvres, but Stanislas Julien urged him to express his gratitude in another way by offering the superior general of the congregation Monsieur Étienne several pieces from the Sèvres factory at the end of the year 1845. The latter reiterated his request in 1847 to Alexandre Brongniart's successor, Jacques Joseph Ebelmen (1814-1852), arguing that it would be necessary to put the prosecutor in good spirits to "ask him [to the future] other services of the same kind, or more important, for example, the acquisition of samples of each of the pieces of antique porcelain which are imitated, with rare perfection, at the imperial factory of King-te-tchin [景德鎮], and more modern pieces made for the Imperial Palace" (SMMN, carton U20, dossier 19, lettre du 22 septembre 1847) or "other articles from the Nanking factory" (id. lettre du 16 septembre 1847).

Experiments

All the types of earth and colours imported by Joseph Ly have been the subject of analyses and experiments. From August 1846, the paste was cooked over high heat in the ovens of the Sèvres factory. The archives of the museum preserve a "minutes of the passage to the great fire of the porcelain kiln of Sèvres, under the mark J. Ly 46 of the materials sent from Kin-te-tching in 1844 by Father Joseph Ly" (SMMN, 4W388). The small cooking cups used for these tests are still conserved at the Musée national de Sèvres. At the same time as these cooking tests on the paste, the manufacture's chief chemist, Louis Alphonse Salvetat (1820-1882) carried out analyses of the elements constituting the different clays and colours. These would give rise to the publication of several memoirs, one published on November 25, 1850 and the other on April 26, 1852, by Ebelmen and Salvetat (Ebelmen J.-J., Salvetat L.-A., 1852). As Antoine d'Albis points out, the main result of this research was to identify one of the essential problems in the use of coloured enamels on porcelain like the Chinese: it was not a question of difference in composition at the level of the colours but at the level of the porcelain clay itself (d'Albis A., 2011, p. 166-167). Furthermore, the same author remarks that the level of iron oxide noted by Salvetat in the analysis of porcelain pastes was particularly high, which tends to demonstrate that the pastes to which Joseph Ly would have had access were not of the best quality (d'Albis A., 2011, p. 170).

Current State of Collections

Some of the samples brought back by Joseph Ly have been identified in the reserves of the Musée de Sèvres, as they are still kept in boxes labeled with the materials’ provenance. What remains is mainly earth and minerals; no trace of coloured enamels and other decorative materials has been discovered. As for the objects, many of them have been erased from the inventory, no doubt following the destruction of the Second World War, the bombardments of which caused serious damage to the Asian collection; only one frog in porcelain enamel remains intact (MNC 3663.10). Nor have the colour samples at École des mines stood the test of time: the musée de Minéralogie MINES ParisTech now only has a handwritten catalogue of the various products imported, followed by translations by Stanislas Julien (MMMPT, Catalog 1336).

The Joseph Ly mission paved the way for a long series of orders for samples and Chinese porcelain by the Sèvres factory spanning the entire 19th century. It is unique in the diversity of the materials gathered, the disparity of their origins in China, and the systematic nature of identification of each imported element.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne