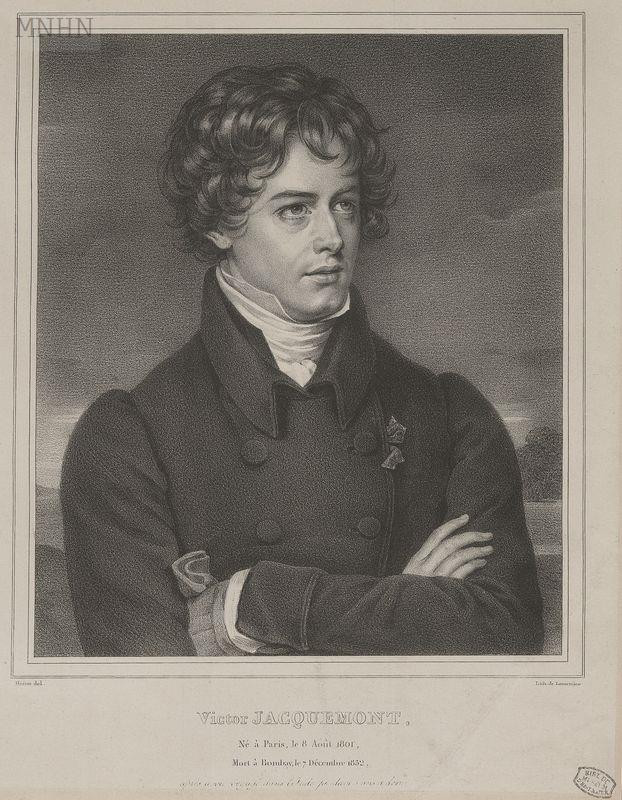

JACQUEMONT Victor (EN)

Biographical article

In 1959, the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle devoted the third volume of its collection ‘Les Grands Naturalistes Français’ (‘Great French naturalists’) to the figure of Victor Jacquemont, focusing on his many passions, ranging from botany to geology, as well as medicine, travel, and literature. This rich volume (Muséum, 1959), complemented by his correspondence (Jacquemont, V., 1833, 1841, 1867, and 1869) and his travel diary (Jacquemont, V., 1841–1844), traces the naturalist’s career over his lifetime, which was as brief as it was intense.

The Jacquemont family

Victor Jacquemont was born on 8 August 1801 (20 thermidor year IX) in Paris, into a family that came from Hesdin in the Pas-de-Calais département. His father, Venceslas Jacquemont (1757–1836), and his mother, Rose Laisné (1770–1818), had four children, including a daughter Louise (1798–1799), who died at a young age. Victor had a very close relationship with his family, at first with his brother Frédéric (1799–1844), the Consul of France on the American continent, then with his elder brother Porphyre (1791–1854), an Artillery Lieutenant-Colonel, who was the main recipient of his letters. His father, who always supported him and helped him in his ventures, was an intellectual figure who lived at the junction of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and attempted to reconcile his religious aspirations and his political convictions (Muséum, 1959, p. 16). He held various posts in the administration, adapting to various historical events, fleeing the Terreur of the French Revolution, and opposing Napoléon Bonaparte (1769–1821).

The formative years

Victor Jacquemont benefitted from an excellent education at the Lycée Impérial (Louis-le-Grand), which he consolidated at the Collège de France, where he attended, in particular, the chemistry courses taught by Louis Jacques Thénard (1777–1857) (Muséum, 1959, p. 16). He suffered an accident during a laboratory experiment, which obliged him to go and live in the countryside for a while, which encouraged him to pursue his vocation as a naturalist. In the home of the Marquis de La Fayette (1757–1834), and subsequently that of Antoine Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836), he enjoyed a life in which humanistic discussions merged with naturalistic considerations (Muséum, 1959, p. 18). At the time, he attended the courses in botany given by René Desfontaines (1750–1833) at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle. He departed on various trips around France, in the North, the Midi, and the Dauphiné, as well as in the Swiss Alps, where on each occasion he forged lasting friendships with the scientists who encouraged him to consolidate his vocation (Jacquemont, V., 1933). In 1822, he enrolled in the École de Médecine de Paris, while continuing to pursue his courses in botany and geology at the Muséum (Muséum, 1959). His formative years were also those in which he became involved in the social world of the salons, in particular that of Georges Cuvier (1769–1832), where he met figures from the literary world, such as Stendhal (1783–1842) and Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870). In 1826–1827, he departed on a trip to America, where he went on trips along the Hudson River. He learned during this period that Louis Cordier (1777–1861), professor of geology at the Muséum, was funding an expedition to India, a part of the world still relatively unknown to French scientists.

The journey to India

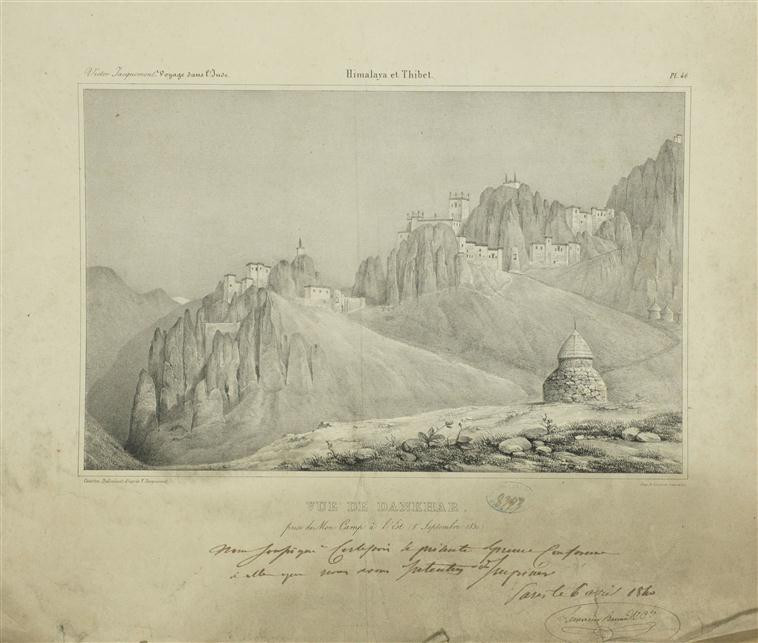

After returning to France in October 1827, he embarked on board La Zélée at Brest on 26 August 1828 for a long, eight-month journey that took him to Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, the Cape of Good Hope, and Reunion Island (former Bourbon Island), where a violent cyclone damaged the ship. On 11 April 1829, he stopped over in Pondicherry, before definitively departing for Calcutta on 5 May. He stayed there for several months to learn Indian languages and perfect his knowledge of Indian botany (Jacquemont, V., 1841, Vol. 1, pp. 80–85). His expedition initially followed the Ganges plain—where he made geological and botanical observations—and took him to Benares. He then made his way to Delhi along the Vindhya mountain range, where he began to assemble his mineralogical collections. His stopover in Delhi enabled him to organise his collections and prepare the next stage of his expedition to Simla in the Himalayan foothills. Driven by his desire to fulfil the mission entrusted to him by the Muséum, he began to explore the Himalayas, climbing to the summit of the Kedarkantha (4,100 m), then the Tibetan slopes. Once he returned to Shimla, where he had left his first collections, he stayed with Captain Charles Pratt Kennedy (17..–1875) and met William Fraser (1784–1835), with whom he struck up a strong friendship (Jacquemont, V., 1833, Vol. 1). Having descended to Delhi via the botanical gardens at Saharanpur, he prepared his journey to the Punjab and Cashmere, with the help of Jean-François Allard (1785–1839), a former general of Napoleonic armies in the service of the Sikh emperor of the Punjab Ranjit Singh (1780–1839). Descending the Sutlej River, he met Ranjit Singh in Lahore, who authorised him to go on a scientific expedition to Cashmere (Duvaucel, A., Jacquemont, V. 2015, pp. 175–275). Jacquemont’s collections were enriched with very important mineralogical, botanical, and zoological specimens. Once he returned to Delhi, he briefly described, packaged, and had his collections sent to France (Jacquemont, V., 1841, Vol. 1, pp. 297–301). Here he prepared the last part of his voyage to Bombay, across the desert plains of Rajasthan and the Deccan Mountains. Wishing to observe the formation of the Western Ghat Mountains Range, he went to the Island of Salsette, several kilometres from Bombay, where he fell sick. Treated in Bombay by Dr John McLennan (1801–1874), who informed him about the serious state of his health, he drafted his will, arranged for his collections to be shipped to France, wrote to his family, and settled his funeral expenses (Jacquemont, V., 1841, Vol. 2, pp. 344–345). He died on 7 December 1832 and was buried the following day in Lonapur Cemetery. His corpse was repatriated to Paris in 1881 and buried in a vault in the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle (AN (French national archives) AJ/15/572). His extensive correspondence was soon published by his friends, in particular by Prosper Mérimée (Jacquemont, V., 1833), and his scientific oeuvre featured in a major publication between 1835 and 1841, under the aegis of François Guizot (1787–1874), who was the French Minister of Public Instruction at the time (Jacquemont, V., 1841–1844).

Victor Jacquemont’s collections

Victor Jacquemont’s naturalist collections comprised 5,800 zoological, botanical, and mineralogical samples (Muséum, 1959). He collected them during his trip to Northern India between 1828 and 1832. Here, he provided a brief description of each sample, ensured they were well packed, and sent them to Paris. A first shipment was prepared in February 1832 in Delhi, from where he departed only on 11 August the same year (Jacquemont, V., 1833). The specimens collected in the meantime were prepared in Bombay, where Jacquemont was treated for a disease that would prove to be fatal. On 30 July 1833, his brother Porphyre Jacquemont gave the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris the handwritten catalogue of the plants he had gathered during his expedition (AN (French national archives), AJ/15/572). The collections, in particular the herbarium, reached the Muséum in November 1833. The Jacquemont herbarium comprised around 4,700 items (Muséum: various categories, Herbier Général; Muséum, 1959, pp. 311–364).

Victor Jacquemont’s work as a portraitist should be added to these collections, as he drew the profiles of the members of his caravan (servants, groom, gardener, interpreter, tailor, boatman, etc.) and drew portraits of the villagers he met in the Himalayas, mountain dwellers, and dignitaries. He also made drawings of the idols he saw in temples. This ensemble is complemented by the geological surveys, profiles, and sections of mountain ranges and valleys (Jacquemont, V., 1844).

Alongside his extensive correspondence, Victor Jacquemont’s scientific journal was published under the auspices of François Guizot by Firmin Didot, the printer for the Institut de France. This monumental edition comprises in total six volumes. The three first volumes, published in 1841, contained the edition of the journal itself (Guizot, F., Firmin-Didot, 1841, 3 Vols.). The fourth volume, published in 1844, contained the descriptions of the collections by scholars from the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris: Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1805–1861) was responsible for the mammals, Henri Milne-Edwards (1800–1885) for the crustaceans, Émile Blanchard (1819–1900) for the insects, Achille Valenciennes (1794–1865) for the fish, and Jacques Cambessèdes (1799–1863) and Joseph Decaisne (1807–1882) for botany (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, I., Milne-Edwards, H., Blanchard, É., Valenciennes, A., Cambassèdes, J., Decaisne, J., and Firmin-Didot, 1844). Two volumes of atlases that were also published in 1844 complemented this ensemble, a volume of plates from the journal and a volume of plates of the described collections (Firmin-Didot, 1844, 2 Vols.). To this end, most of Jacquemont’s drawings were reproduced by engravers and lithographers, such as Hubert Roux (17..–18..) and Louis Courtin (18..–18..). With regard to the collections, specialised draughtsmen were solicited, such as Werner for the mammals, A. Prévost for the birds, S. Cudart for the crustaceans, and E. Delile for botany, although the biographical elements (dates and first names) have not yet been identified.

In the field of geology, the samples, stones, and fossils brought back by Jacquemont, along with the profiles and sections drawn in situ, were a pioneering work. from this perspective, the Himalayan regions, in particular, were still relatively unknown.

In the field of botany, the Jacquemont herbarium was complemented by a handwritten catalogue divided into three parts: from Calcutta to Delhi and the Himalayas; Punjab and Cashmere; and from Delhi to Bombay. The 4,700 samples were numbered and the plants described in Latin, most often named and characterised by the locality and environment in which the sample was collected (Herbier Général, Muséum).

In the field of zoology, the shipments were less abundant due to the requirements of naturalisation and preservation. Several species were dedicated to Jacquemont, such as the Jacquemont Cat (Felis Jacquemontii).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne