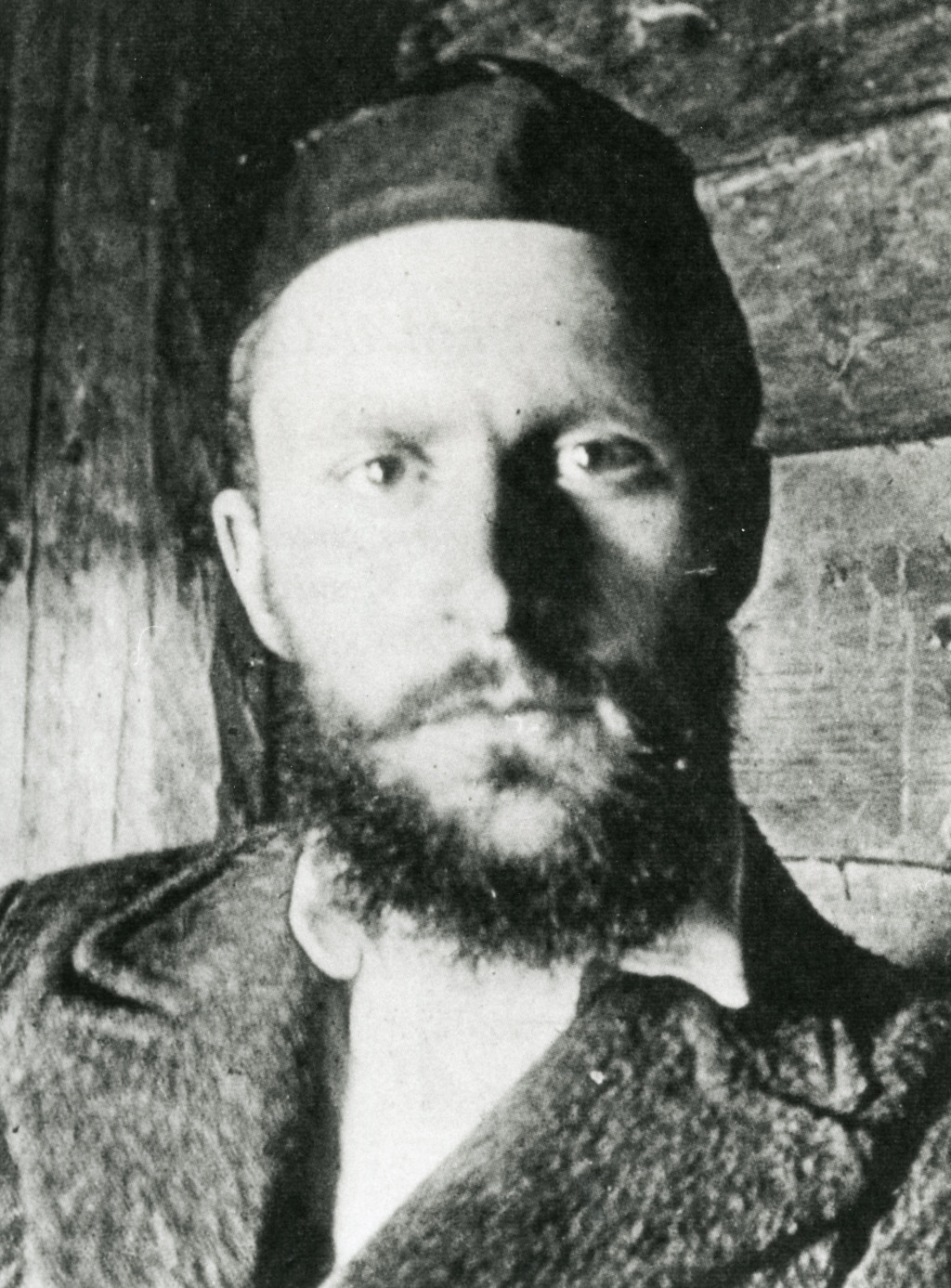

BACOT Jacques (EN)

Biographical article

In his youth, Jacques Bacot was not interested in the ceramic factory owned by Raymond Bacot in Briare (Loiret). Yet, being a traveler, a member of the Geographical Society as well as hosting explorers at home, he passed his love of travel on to his son Jacques. He too had inherited this from a father who was an avid traveler. Jacques Bacot often read his grandfather's travel diary. The financial well-being of the family would lead him in turn to take to the road. At the age of twenty-seven in 1904 he undertook a journey around the world. He discovered Asia in Indochina and met the Pères des Missions étrangères. He listened to the explorations of North Asia that propelled Central Asia to center stage, while Tibet still remained a blank spot on the map. People talked of the myth of Tibet, the land of the wise. In addition, he read articles written by German missionaries about Western Tibet, French missionaries about Eastern Tibet along with the development of photography, that produced the first photo of the Potala in 1901. The studies of Tibetan Buddhism iconography along with the acquisition of the first Tibetan painting by the Musée Guimet in 1903 were testament to the new found famed of this mysterious country. It was due to this that Jacques Bacot made his first trip to Tibet from March to December 1907. Despite the warnings of the Pères Missionnaires, he arrived via Yunnan and traveled the region on the Eastern between the Salouen, the Mekong and the Blue Rivers. The bloody revolution of the Tibetans against China, between 1905 and 1906, had just ended in the region. Jacques Bacot's group included two interpreters: one for Chinese, who had accompanied Prince Henri d'Orléans and another for Tibetan. Despite the danger, Jacques Bacot presented himself as a simple "tourist", not as an explorer, because he was on a well-known route to the Tibetan province of Tsarong. He became the first European to travel the Dokerla mountains, a famous pilgrimage destination in Kham located between the Salouen and the Mekong, after having escaped being spied on by his escort as well as the Chinese authorities. But it did force him to cancel an expedition towards the small kingdom of Pöyul, west of Kham. During this first visit he reveals through his writings the spirit of a traveler and explorer as well as his taste for freedom (Bacot J., 1909). He was an apt observer of the flora and fauna which he described with his signature lyricism and the humor. He wass also seduced by the Tibetans and their wisdom; ultimately fascinated by the country.

He returned to France with a Tibetan from Patong named Adjroup Gompo. In 1908, he entered the Société Asiatique and became a student at the EPHE, in the historical and philological sciences department. He enrolled in Sylvain Lévi’s (1863-1935) courses who also headed the “Indianism Chair”, to which Tibetan studies were attached. Bacot began the translation of a Tibetan dialogued version of the Vessantara jâtaka, the previous life of the Buddha (Bacot J., 1914). After having learned spoken Tibetan with Adjroup Gompo he returned to “rebellious Tibet” in May 1909 and did not return until March 1910 (Bacot J., 1912). Although the political situation was even more threatening due to the Sino-Tibetan war, Bacot braved the danger due to information provided by Father Monbeig (1875-1914) a missionary in Tsakou on the Mekong. He crossed all of Kham, following a route that was then largely unexplored. He reached Lithang via the Nyarong region yet was unsuccessful in getting to the mysterious kingdom of Pöyul, then named Nepemako which was the legendary promise land of the Tibetans. Nonetheless, the journey became an inner quest of the Tibetan soul by his immersion in the culture. He also made a fortuitous and important discovery: finding the Eastern source of the Irrawady river. He left Tibet with great regret due to the Chinese threat and the risk of looting of the boxes of documents he had amassed. During the winters of 1913-1914 and 1930-1931 he made trips to the Himalayas, notably to Kalimpong, in Sikkim (Lebègue R., p. 3).

As a Tibetologist he studied multiple aspects of the culture including popular language and culture. Bacot published a study on the populations of eastern Tibet in 1912, then another on the Mosso, a very poorly known ethnic group in the south-east of Kham in 1913. That same year, he married Marguerite Thénard from Burgundy; granddaughter of the chemist Louis-Jacques Thénard (1777-1857). His contribution to the study of Tibetan, whose richness he admired, was significant. In 1914, he graduated from the EPHE, but was called to enlist in August. He became an officer in a territorial infantry regiment, then in September 1917 was attached to the French military mission in Siberia, led by Paul Pelliot whom he had the opportunity to meet. His career as a Tibetologist really began in 1919 when he began teaching Tibetan on a voluntary basis at the EPHE at the request of Sylvain Lévi. In 1936, Bacot became director of Tibetology studies, a position that had been created for him. Jacques Bacot continued to defend the essence of Tibetan culture, including it literature. He had brought back a collection of Tibetan books from his travels which he bequeathed to the Société Asiatique at the end of his life. Many are his articles on the Tibetan language and its grammar. But he was also interested in Tibetan theater and published some important papers on the subject. The great mystics of Tibetan Buddhism were also an interest and his talent as a translator was exemplified in the publication of the life of the poets Milarepa (1925) and Marpa (1937). The geography and history of Tibet are not to be overlooked: in 1920, Jacques Bacot become a member of the Comité Français de Géographie, then the Commission Centrale de la Société de Géographie. In 1940, the Tibetologist began translating Tibetan documents relating to the history of Tibet, brought back from Dunhuang by the Pelliot mission. This work did not appear until after the war, during which he housed a resistance group at his home. It was finally published in 1946, in the “Annals” of the Musée Guimet in collaboration with F.W. Thomas and C. Toussaint. One of his last books was an introduction to the history of Tibet, published in 1962. Bacot’s remarkable and lengthy bibliography is testament to his relentless work up to the end of his life.

The collection

After his second trip, Jacques Bacot presented his vision of Tibetan art in a lecture given at the Musée Guimet in February 1911, which consisted of presenting his collection catalogue published in the same year by Joseph Hackin ( Hackin J., 1911, pp. V-XXII). At the time, his had an innovative vision of Buddhist paintings and sculptures from Tibet which had not been recognized as works of art. He emphasized upon the richness, originality and quality of Tibetan art, while being timeless as well due to little iconographic or stylistic evolution which made them impossible to date. Nevertheless, the collection he amassed during his two trips clearly dates from the 18th and 19th centuries. It proves Jacques Bacot's taste for the decorative aspect of Tibetan painting representing the large part of his collection. Having only traveled the east of Tibet on the Sino-Tibetan borders, Jacques Bacot acknowledged that he had an incomplete understanding of Tibetan art. The collected works include a number of Chinese aspects (landscapes, colors, etc.) that are characteristic of this region. He built his collection throughout the two trips to the region. But he was not a collector in the classical sense of the term, having never bought works at public sales.

During his first stay, he acquired objects from a Chinese soldier that were from Lama monasteries located between Tatsienlou and Bathang (Bacot J., p. 26). These objects were exhibited in 1908 at the Musée Guimet, along with other Tibetan pieces belonging to the Péralté collection (Hackin, J., 1908). Part of a collection of primarily Buddhist objects there are a few bönpo pieces, i.e. belonging to the ancient religion of Tibet. The collection was further enriched during Jacques Bacot's second trip to eastern Tibet. This is why the Musée Guimet held an exhibition that was solely devoted to his collection in 1911 (Hackin J., 1911). Here again, the exact provenance of the objects is unknown.

The 1912 donation to the Musée Guimet

At the beginning of 1912 Bacot made a decision to gift a part of his Tibetan collection to the museum which signaled an important moment in the history of the institution. In a thank you letter to Jacques Bacot dated March 28, 1912, Émile Guimet underlines the great scientific and artistic interest of this generous gift. This marks the true beginning of the Tibetan section of the museum, even though a low quality painting previously entered its collection in 1903. This collection also includes works that were not presented at the 1911 exhibition. Among more than seventy thangka (painted scrolls), the highlight of the donated pieces and one of the most remarkable iconographical ones was that of the protective goddess Palden Lhamo, due to its size and quality (Béguin G., 1995, p. 261- 262). It was, without a doubt, the masterpiece of the Jacques Bacot collection at the Guimet museum. The set of thangkas is of great iconographical richness: Buddhas and narrative paintings illustrating episodes of his life, bodhisattvas, religious figures, deities with peaceful or terrible appearances, mandalas, etc. There were also many ritualistic and liturgical objects made from different materials including textiles even though many were made of metal: stupa, prayer wheels, reliquaries, musical instruments, dagger, bell, cleaver, cups, bell, ex-voto (tib.tsa-tsa ), censers, rosaries… Among the most interesting statuettes are, again, a Sino-Tibetan style representation by Palden Lhamo (Béguin G., 1989, p. 20-21). There was also a very decorative gilded copper image of Padmasambhava, a famous tantric master from North-West India, seated on a lotus between his two mystical Indian and Tibetan wives (Béguin G., 1991, p. 40). The aesthetics of two statuettes reflect the diversity of this art and of the collection built by Jacques Bacot. Certain works of a “popular” nature are testament to Jacques Bacot's appreciation of this aspect of the Tibetan culture, and several thangkas seem to illustrate religious plays (Béguin G., 1995, p. 387-388).

The 1951 sale at the Musée Guimet

In 1951, Bacot’s 1912 donation was enriched by the Musée Guimet purchasing a statuette and twenty-two paintings, most of which date from the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century, from the Tibetologist. The Société Asiatique, of which Jacques Bacot was then the President, was in a difficult financial situation and so Bacot donated the proceeds of the sale.

Donations to the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme also benefited greatly from the generosity of Jacques Bacot, who donated paintings and numerous Tibetan ethnographic objects, i.e. a set of around 290 pieces between 1931 and 1938. In 1937, he gave another donation, consisting of thirty-eight objects that he had purchased from Father Georges André (1891-1965) of the Mission étrangères de Paris (Dupaigne B., 2001) who was then on leave in France. The latter had acquired them from the Yunnanfou (China) region between 1921 and 1931. Jacques Bacot foresaw the revelation of the richness and variety of Tibetan art and its history in the 20th century.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne