LANSYER Emmanuel (EN)

Biographical article

An academically trained painter who adopted a realist approach, Lansyer was an artist known primarily for his seascapes, landscapes, and architectural views. A passionate collector and writer of poems, he also painted portraits, still lifes, and Japanese-inspired watercolours, in the form of fans. His career reached the height of success in 1881, when he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur and became a member of the Salon’s jury.

Family background and artistic training

Emmanuel Lansyer was born on 19 February 1835 in Bouin, a small village in the Vendée, and passed away in Paris on 21 October 1893, at the age of fifty-eight. At the age of three, he moved with his family to Machecoul, as his father, Fidèle Alexandre Lansyer (born in 1880), had taken up a post as a doctor at the Collège de Pontlevoy.

In 1847, Lansyer studied at the Collège Royal in Nantes, where his parents sent him due to his poor performance in school. This was a very difficult period for him and he sought relief in drawing, a subject in which he was awarded a prize each year. His talent was appreciated by his teachers, in particular, by Père Laydet, an amateur painter, who made him copy his own studies. During his days off, Lansyer spent his time in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, where he studied the works of Camille Corot (1796–1875), Charles-François Daubigny (1817–1878), and Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867) (Blacas, D., 2004, p. 8).

His parents disagreed with his wish to become a painter, in particular his father, who had a notarial career or one in financial administration lined up for him. The young man was therefore obliged to accept a compromise and decided to study architecture. In 1855, he began to learn the métier with his architect cousin Alfred Dauvergne (1824–1885)in Châteauroux. Two years later, he completed his training in Paris. Here, Lansyer joined the studio of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879), where he learned the various technical processes of drawing (Blacas, D. de, 2004, p. 10). His work was appreciated by his master, who offered him a post as a departmental architect. Determined to become a painter, Lansyer turned down this opportunity and told his parents about his decision, which led to a very violent reaction from his father, who cut off his allowance, although his mother continued to send him money (Blacas, D. de, 2004, p. 11).

In Paris, Lansyer attended classical drawing courses at the École Nationale run by Lamotte, a painter of historical subjects and outdoor scenes. His charcoal work Paysage d’Hiver, which was accepted at the 1861 Salon, was favourably received by the critics. In December 1861, he joined the studio that Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) had recently opened in Paris, and here he trained in oil painting with the master of realism. This experience only lasted several months, but it was a decisive step in the young artist’s career. In August 1862, Lansyer was admitted to the studio of Henri Harpignies (1819–1916) in Cernay, where he resumed his outdoor studies, with the help of his master’s advice, as a result of which Lansyer eventually found his vocation in landscape painting. He returned to Cernay on several occasions (1869, 1875, and 1877).

Lansyer presented his first painting at the 1863 Salon, but it was refused. Hence, he decided to exhibit the work at the Salon des Refusés, where it did not go unnoticed and even achieved some success (Blacas, D. de, 2004, pp. 12–13).

Lansyer, an itinerant painter

Lansyer usually spent the winter in Paris, when he worked on the pictures he wished to submit to the Salon, and travelled the rest of the year.

In 1863, Lansyer left for Finistère. He settled in Douarnenez, where he met other painters and various Parnassian poets, such as Sully Prudhomme (1839–1907) and José Maria de Hérédia (1842–1905) amongst others, with whom he struck up friendships. He soon became a prominent figure in this small Brittany-based circle of artists and poets. In this pastoral and marine setting, which he returned to for fourteen years, Lansyer spent many hours painting outdoors, inspired by the luminous contrasts and plants (Blacas, D. de, 2004, p. 14).

In 1868, Philippe Burty (1830–1890) commissioned an engraving from him entitled La Fontaine for his volume Sonnets et Eaux-Fortes published the following year (Bailly-Herzberg, J., 1985, p. 177).

In 1870, Lansyer went on a voyage of discovery of Italy and visited Rome. The following year, the landscape artist was drawn to the sunny south of France. He returned there circa 1890 in search of a temperate climate, on the advice of his doctor, as he was suffering from health problems (Blacas, D. de, 2004, pp. 140–143).

Circa 1875, Lansyer stayed in his native region—which was relatively ignored by artists—, where he captured the effects of the light and devoted himself to representing the salt marshes, particularly at sunrise. He then headed north, to Lille, and afterwards to the coasts of Normandy, drawn by the power of the waves and the rocky masses. The latter were the subject of studies on the Île d’Ouessant, which he visited in August 1885, fascinated by the wild landscapes (Blacas, D. de, 2004, pp. 23–24; 48). As of 1882, Lansyer focused on a series of studies at Parthenay, Clisson, and the Château de Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet. His talent came to the fore, in particular, in his views of the French architectural heritage; this is evident, for example, in the Belvédère du Petit Trianon,which was presented at the 1889 Salon (MO, inventory no. RF624). Amongst the many places that inspired his pictures, were the Vallée de Chevreuse, the Forest of Yvelines, the Mont-Saint-Michel, Granville, Loches, in particular its château, Menton, and Venice, where he lived for over one month in 1892. In 1889, during the Exposition Universelle, the City of Paris commissioned two series of views from him: the first related to the capital city’s streets and the second was devoted to buildings bearing commemorative plaques (Blacas, D. de, 2004, p. 164).

The Musée Lansyer in the artist’s home

In the interest of posterity, Lansyer drew up an inventory of his works and those in his collection, along with his biography. A passionate collector, he probably began to buy Chinese and Japaneseobjects d’art in the 1870s from curiosity shops and dealers of Asian art based in Paris. Lansyer often frequented auction rooms, where he purchased various objects for his Oriental Collection (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 88).

Lansyer bequeathed his family home to the Town of Loches, along with 6,000 objects, including almost 500 pictures, around 2,000 engravings, more than 1,000 Asian objects, almost 2,000 photographs, his library, and his personal objects. However, the donation was subject to certain conditions, which he specified in his will: ‘In Loches, in my above-mentioned house, a museum will be created that will be known as Maison Lansyer and which will be permanently maintained at the expense of the Town of Loches. (…) Once the necessary sum for the museum’s first installation has been deducted from the capital I have bequeathed, the revenue from the remaining capital shall be solely devoted to the maintenance, embellishment, and extension of the museum and its collections (…)’(MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)). The Loches Municipal Council accepted the Lansyer bequest during the session of 7 November 1894 and on 13 July 1902 the Musée was inaugurated (Blacas, D. de, 2004, p. 166).

The Musée Lansyer in the artist’s home in Loches houses a significant number of pictures and Lansyer’s sketchbooks; his works are also held in other institutions, such as the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée Carnavalet, and the Musées des Beaux-Arts in Tours, Rennes, and Quimper.

Distinctions

Emmanuel Lansyer was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1881. The award, comprising a star with five points, was bequeathed to the Town of Loches in 1893, along with other awards. Lansyer obtained various medals during his career: at the 1865, 1869, 1876, and 1881 Salons, the 1867 Exposition de Carcassonne, the 1872 International Exhibition in London, the 1873 Universal Exhibition in Vienna, the LondonInternational Exhibition of Arts and Industries, the 1880 Salon des Arts Décoratifs, the 1882 Exhibition des Arts Décoratifs, and the 1883 Amsterdam exhibition. As of 1881, and until 1891, Lansyer was a member of the Salon jury (MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)).

The collection

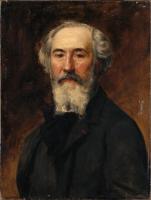

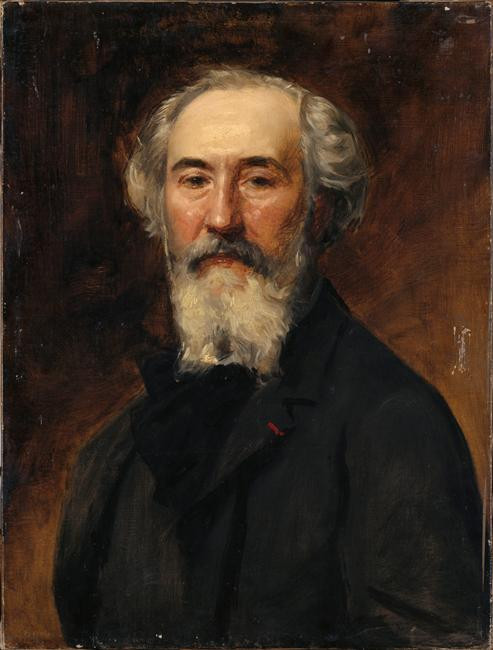

Lansyer was a multifaceted collector. He was interested in paintings and drawings by past and contemporary artists, including Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Viollet-le-Duc. He was particularly interested in engraving, and he compiled a remarkable collection that comprised examples of works associated with Canaletto (1697–1768), Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Victor Hugo (1802–1885), Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), and Corot. His collection also comprised portraits and sketches of him executed by various artists, including François Louis Français (1814–1897), Augustin Feyen-Perrin (1826–1888), Auguste Alexandre Hirsch (1833–1912), James Tissot (1836–1902), and Carolus-Duran (1837–1917). He also owned a large collection of around 2,000 photographs, some of which were very rare (MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)).

Like many artists of his era, Lansyer was also fascinated by East-Asian art, in particular Chinese and Japanese art, and he assembled a collection of no less than one thousand objects. In his will drafted on 11 September 1891 (MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)). Lansyer left some of the pictures and drawings he owned to his friends and institutions, such as his portrait of Carolus-Duran (1837–1917), which he bequeathed to the Musée du Luxembourg, and is now held in the Musée d’Orsay (inv. no. RF 1127, LUX 751). As for the rest of his property, he decided to bequeath it to the Town of Loches. In particular, regarding his collection of Asian art, he specified: ‘I give and bequeath to the Town of Loches all the objects in my collection of Chinese and Japanese bronzes and all the objects in my collection of Japanese lacquered objects; shelves, panels, boxes, trays, my entire collection of kakemonos, paintings on silk, my entire collection of fabrics and Chinese and Japanese costumes, weapons, armour, black and white or colour albums from Japan, cloisonné enamels, bamboo boxes, screens, faïence, and porcelain and all kinds of other objects, all of which are Chinese and Japanese’ (MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)).

Lansyer probably began to collect Chinese and Japanese objects in 1872. Indeed, this date marked the first sale at auction of his works, which sold for twenty-eight thousand francs, and henceforth he was able to lead a comfortable life, as he continued to sell works to private individuals rather than dealers. Up to this point, he had lived in a modest pied-à-terre in Montparnasse, as he lacked the means to rent a real studio.

Lansyer very probably bought his objects in Paris, in the curiosity shops and galleries that exhibited Chinese and Japanese art and objects d’art, many of which opened in the 1860s (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 60–66).

It is difficult to confirm that the painter purchased objects at the 1867, 1878, and 1889 Expositions Universelles; but it is very likely that like other artists of his time, he took the opportunity to visit the Chinese and Japanese sections, which were highly successful with the general public and collectors. Incidentally, Lansyer did attend auctions, above all between 1872 and 1874, often accompanied by his friend, the poet José Maria de Hérédia (1842–1905), with whom he shared a passion for Chinese and Japanese arts. (MMLL, Fonds Lansyer, (inv. no. unknown)).

Several objects from his collection of Asian art were presented at public events, such as the seventh exhibition of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs held in 1882 and the retrospective exhibition of Japanese art held by Louis Gonse (1846–1921) in 1883 (Catalogue de l’Exposition Retrospective de L’Art Japonais, 1883, p. 409). This attracted the attention of collectors and experts, such as Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896) and Paul Gasnault (1828–1898), who praised the various objects that belonged to the artist (Gasnault, P., 1883, pp. 253–254). Lansyer’s collection of Asian art included fukusa made with very precious satins and the copious use of strips of gilded paper. This was a particular type of fukusa, called kakebukusa, which was used to cover a gift placed on a tray during special celebrations, such as weddings. The fukusa were without doubt the most remarkable objects in the Japanese collection assembled by Lansyer. As for the other objects, worthy of mention were various bronzes dating from the nineteenth century, which were present in other collections at that time, such as that of Henri Cernuschi (1821–1896). Like the textilesand bronzes, the other articles in the collection show that Lansyer’s taste for Japanese art was very similar to that of his contemporaries, above all in relation to prints, albums, and illustrated books. The collection also comprised prints, including various complete series. Most of these engravings were created by artists from the Utagawa School, such as Toyokuni I豊国 (1769–1825), Kunisada 国貞 (1786–1865), Kuniyoshi国芳 (1797–1862), Sadakage 貞景 (active 1818-44), and Yoshitora 芳虎 (active 1850–80). Amongst the many prints on crepe paper, which were widely available and highly appreciated in the artistic circles of the second half of the nineteenth century, were works by Utagawa Hiroshige II 歌川広重 2代目 (Shigenobu) (1826–1869) and Toyohara Kunichika 豊原国周 (1835–1900). Illustrated books and albums were largely present in the collection of Lansyer, who, like the other specialists on Japan of his epoch, appreciated the genius of Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760–1849).

The inventory drawn up by Lansyer also mentions a series of eighteen kakemono and two screens, most of which were illustrated with themes inspired by the natural world. This suggests that one of the aspects that convinced the painter, aside from the various collectors of his era, was the attention paid by Japanese artists and craftsmen to the plant and animal worlds. The collection of Emmanuel Lansyer, who was one of the very first specialists on Japanese objects, is one of the very rare collections of Eastern Asian art that have remained intact. It attests to the painter’s tastes in Japanese art and provides invaluable information about the quality and variety of Chinese and Japanese objects that could be found in Paris between 1870 and 1890.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne