DE NITTIS Giuseppe (EN)

Biographical article

Giuseppe De Nittis was one of the most important figures amongst the Italian artists living in France in the second half of the nineteenth century. A painter of modern life, he represented with originality the life of his times, focusing on the avenues, squares, places for social encounters, and female elegance and beauty. A talented landscape artist, he skilfully represented natural scenes and urban views. Passionate about Japanese art, in particular paintings and textiles, he was one of the most refined collectors of his times.

The family milieu and artistic beginnings

Born on 25 February 1846 in Barletta, in Italy, to a wealthy family of rich landowners, De Nittis soon became an orphan. His mother, Teresa Maria Emanuela Barracchia (d.1849), died shortly after his birth, and his father, Michele Giuseppe Raffaele De Nittis (d.1856), who had been imprisoned for political reasons, committed suicide several years after his release from prison. The painter and his three brothers, Vincenzo, Francesco (d.1848), and Carlo, were entrusted to their grandparents, until Vincenzo, the eldest, took on the role of guardian for his brothers (Dini, P., Marini, G. L., 1990, Vol. I, p. 85)

From his earliest childhood, De Nittis had a certain penchant for painting, encouraged by his first drawing teacher, the artist Giovanni Battista Calò (1833–1895). In 1860, the De Nittis brothers moved to Naples. The young painter was entrusted to a drawing teacher, Vincenzo Dattoli (1831–1896), and, on 23 December of following year, he enrolled at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. He frequented the painters Federico Rossano (1835–1912), Marco De Gregorio (1829–1875), and other artists who were older than him, representatives of the Scuola di Resina (School of Resina), otherwise known as the ‘Republic of Portici’, whose artistic principles, based on direct observation and the study of nature, he shared. Neglecting to attend his courses at the Academy, De Nittis joined the group, and on 2 June 1863 he was expelled from the Institute. (Dini, P., Marini, G. L., 1990, Vol. I, p. 86)

De Nittis’s years of Neapolitan training were also very significant due to his encounter with the Florentine sculptor Adriano Cecioni (1836–1886), with whom he struck up a friendship. The latter encouraged the young artist and transmitted his own passion to him (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 23). When, at the age of eighteen, De Nittis presented for the first time two small scenes of identical subjects (L’Arrivée de la Tempête, ‘Imminent storm’) for the exhibition held in 1864 by the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti(Mascolo, R., 1992, p. 9), Cecioni was taken with the works and predicted a promising career for De Nittis. The young painter also took part in exhibitions held by the Società Promotricein1866 and 1867, where two of his pictures, including the famous Traversée des Appennins (Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, inventory no. 61 PS), were bought by King Victor Emmanuel II (1820–1878) (Cecioni, A., 1905, p. 359). Again, it was Cecioni who introduced De Nittis to the Macchiaioli (a group of Italian outdoor painters active in Tuscany in the second half of the nineteenth century).

During the summer of 1867, De Nittis went on his first trip to Paris. Several days after his arrival, he met the painter Edouard Emile Pereyra Brandon (1831–1897), who introduced him to Jean-Louis Gérôme (1824–1904). He then met Ernest Meissonnier (1815–1891), who suggested that he work in his studio. On the advice of Cecioni, De Nittis cordially turned down the offer. During this stay, De Nittis also met the dealer Adolphe Goupil (1806–1893), who purchased several works from him. After spending two months in Florence with the Macchiaioli, he returned to Naples to devote himself entirely to painting. In autumn 1868, he returned to Paris, where he worked for the dealer Frédéric Reitlinger and he subsequently signed a very advantageous contract with Goupil (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 34).

On 29 April 1869, De Nittis married Léontine Lucile Gruvelle (1843–1913). Their son Jacques (1872–1907), born on 19 July 1872 in Resina, was held over the baptismal fonts by Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894) (Mascolo, R., 1992, p. 11).

The painter’s career

The works produced during De Nittis’s first Parisian period were influenced by the fashion for pictures of figures dressed in historical costumes. At the 1869 Salon, as Gérôme’s pupil, he presented Une Forêt des Pouilles (current location unknown) and Une Visite chez l’Antiquaire (private collection). The works exhibited at the 1870 Salon, La Femme aux Perroquets (private collection) and Une Réception Intime (current location unknown), attest to the influence of Meissonnier’s pictures (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 36).

In 1869, De Nittis also produced his first work with a Japanese theme. This picture, entitled Japonaise Endormie, is mentioned in the records of the Maison Goupil, now held in the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. These documents attest to the fact that the work, which was brought to the Maison Goupil on 24 November 1869, was sold to the dealer Reitlinger on 26 November that year for 1,200 francs. Unfortunately, in the photographic albums at the Maison Goupil there is no image of this work, whose fate is unknown. Furthermore, the books in the Maison Goupil mention another work with a Japanese theme, a watercolour, painted in 1870. Entitled Japonaises, this watercolour was sold to the collector James H. Stebbins for 2,500 francs on 21 November 1871. The work featured in the catalogue of the Stebbins Collection Sale that was held in 1889 at the American Art Association in New York, but its current location is unknown (De Nittis, 2013, pp. 51–52).

Between 1870 and 1873, De Nittis and his wife spent long periods in Italy, in Apulia and Naples, where the painter produced remarkable works, such as La Route de Naples à Brindisi (R. Eno Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art), which received an honourable mention at the 1872 Salon and was a great success. In Naples, De Nittis spent an entire year climbing the slopes of Vesuvius to sketch the various phases of the eruption. He sent several of these studies to the 1872 Esposizione Nazionale di Belle Arti (National Fine Arts Exhibition) in Milan and the Salon of that year. Goupil, who considered these works too realistic, suggested that the painter insert several figures of tourists to make the scenes more picturesque and easier to sell. The artist eventually made the requested modifications, but shortly after, in June 1874, terminated his contract with the dealer. Although De Nittis had incurred a large debt with Goupil, he decided to sell his own canvases and recuperated the pictures that remained with the dealer. In 1890, six years after her husband’s death, Madame De Nittis had not yet fully settled this debt (Dini, P., Marini, G. L., 1990, Vol. I, p. 100).

De Nittis’s return to Paris marked the beginning of a new turning point in his artistic themes: the painter now focused on modern life, in particular the city’s avenues, squares, and boulevards, as well as social venues such as theatres and racing tracks. He also represented Parisian ladies at their toilet, and portrayed them as they strolled around the city. The pictures executed between 1874 and 1884, such as Fait-il froid !!! (How Cold it is!, private collection),exhibited at the 1874 Salon along with two other works, attest to his quest to become one of the most original painters of Parisian life. On the invitation of Edgar Degas (1834–1917), De Nittis exhibited five works in the first Impressionist exhibition, but they were not mentioned in the catalogue and were very poorly presented, which probably explains why he did not accept the invitation to participate in the second edition of this event scheduled to be held in April 1876 (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 41). Between 1873 and 1879, De Nittis went to London on several occasions staying in the city for a few months at a time (Mascolo, R., 1992, pp. 11–14). Here, he met the banker Kaye Knowles, one of his greatest patrons, who purchased twelve pictures from him, for whom the Italian painter represented the most emblematic places in the English capital, skilfully conveying its mists and urban views. In London, De Nittis also met James Tissot (1836–1902), with whom he struck up a friendship (Dini, P., Marini G. L., 1990, Vol. I, p. 103). His participation at the 1876 Salon was marked by his first official award for his picture Place des Pyramides, which is now held in the Musée d’Orsay (inventory no. RF 371, LUX 205). The works presented in the 1877 Salon were also remarked by the critics and attracted the attention of Degas, in particular two watercolours, Le Boulevard Haussmann (private collection) and La Place Saint Augustin (private collection). It was during the 1878 Salon and the Exposition Universelle of the same year, where he presented a significant ensemble of twelve works, that De Nittis reached the height of success and celebrity, obtaining a gold medal and being made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (Mascolo, R., 1992, p. 14). During these years of success, the artist continued to participate in public exhibitions and hold solo exhibitions in France and abroad. In 1879, De Nittis exhibited works in the galleries of La Vie Moderne, a periodical directed by Émile Bergerat (1845–1923), of which he was one of the artistic collaborators and for which he designed, amongst others, the cover of the first issue published on 10 April 1879 (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 45). In 1876, De Nittis started working with pastels. Initially adopting this technique only for studies and sketches, he then used it to create autonomous, often large-format works, which he presented as of 1879 at the King Street Galleries in London. It was above all two events—the 1880 exhibition in the gallery L’Art and that held in 1881 at the Cercle de l’Union Artistique, on the Place Vendôme—that brought his pastels to the attention of the general public and attracted the attention of other artists and the critics (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 46–47). The last years of De Nittis’s life were very difficult, not only as a result of health problems, as he contracted very severe bronchitis, but also due to quarrels with the painters Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841–1920) and Alfred Stevens (1823–1906), with whom he held the 1882 Exposition Internationale de Peinture. Over the same period, his relationship with one of his closest friends, Edmond de Goncourt, deteriorated. To take care of his health and that of his son Jacques, who had a lung disease, De Nittis and his family spent several months in Naples between the end of 1883 and the beginning of 1884. During this stay, the artist discovered that various fakes of his works were circulating in Italy, which caused him much dismay. When they returned to France, the De Nittis family moved to their country house in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where the painter died from a stroke on 21 August 1884, at the age of thirty-eight (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 52).

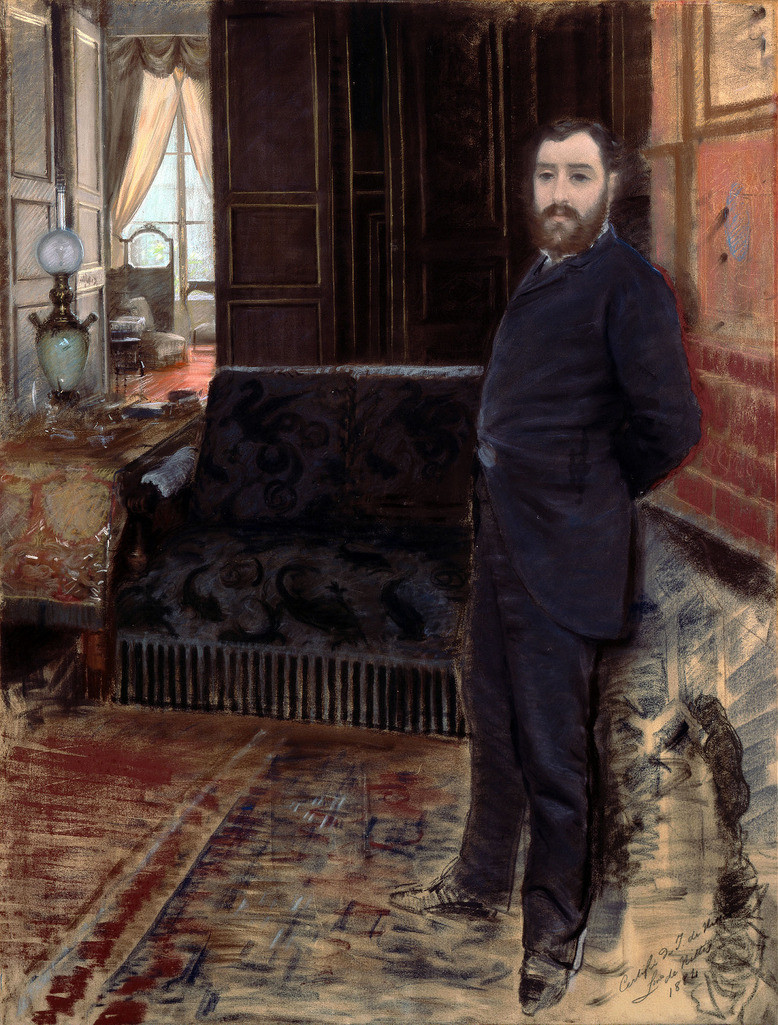

High society

A decade after his arrival in Paris, De Nittis became a successful artist and he and his wife enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle. In 1880, the De Nittis couple left the mansion on the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne and moved into a more luxurious residence. They purchased land in an elegant district of the Plaine-Monceau, where they had a four-storey mansion built, complemented by a garden and two very well-lit studios (Degas e gli italiani a Parigi, 2003, p. 414).

The Italian artist’s new status brought him into contact with the most famous personalities in the literary circles of the times, including Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896) and Émile Zola (1840–1902), and he established friendships with various artists, including Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917). In 1878, the couple began to regularly invite not only artists and intellectuals, but also politicians, doctors, and wealthy bankers to the house on Saturday evenings. In addition to the likes of Degas, Zola, and Goncourt, the De Nittis were visited by the Princesse Mathilde Bonaparte (1820–1904), Philippe Burty (1830–1890), Jules Claretie (1840–1913), Alphonse Daudet (1840–1897), José Maria de Hérédia (1842–1905), and Alexandre Dumas (1824–1895), the author’s son, amongst others. There were also all the Italians who lived or were passing through Paris, such as the painter Rossano, the journalist Jacopo Caponi (1831–1909), and the art critic Diego Martelli (1839–1896) (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 49–50). It was Madame De Nittis who maintained these relations, handled her husband’s correspondence, and invited the guests, whose names she noted down on invitation cards (Carnets de comptes et des invitations des De Nittis, Piero Dini Collection, Italy). The soirées held by the De Nittis soon became so popular that members of high society were ready to pay high prices for the Italian artist’s pictures just to be able to receive an invitation to his residence, according to Edmond de Goncourt: ‘At that time, curious things occurred at the end of the century. Hence, the wealthy Bellinos would pay 50,000 francs for a picture by Nittis, not because of the artist’s talent, but rather to be invited to his home and make contact with people in high society’ (Goncourt, E., and J., 2004, Vol. II, p. 975). During these social events, the master of the house would cook succulent dishes that he offered to his guests. Furthermore, the setting in which these parties took place always enchanted the guests due to the refinement of the decorations (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 49). Alidor Delzant (1848–1905), the Goncourt brothers’ biographer, who knew De Nittis during his lifetime, described the luxurious decorations in the painter’s mansion, on the occasion of the reading of several passages of Edmond de Goncourt’s La Faustin:

On 7 [sic] April 1881, the painter Giuseppe De Nittis invited several close friends, Rue Viette [sic]; in the vast hall there were Oriental carpets, foukousas, and kakemono canvases on easels, and pastel sketches added a decorative touch with bright colours and harmonious mosaics. Delicate Chinese parasols captured and softened the light from the two chandeliers. Sitting on a large divan shaded by a silken vellum, which was like a dyed canvas, the mistress of the house was accompanied by Madame Alphonse Daudet, Madame José Maria de Heredia, Madame Zola, and Madame Georges Charpentier. Around them stood their husbands, along with Messrs Ph. Burty, Huysmans, Céard, and Alexis (…) (Delzant, A., 1889, pp. 229–230).

It was in this exotic and luxuriously furnished setting that Goncourt read out several extracts of the novel he dedicated, once finished, to his Italian friend, inserting on the first page the dedication: ‘À J. de Nittis’ (Giuseppe De Nittis: La Modernité Élégante, 2011, p. 58). De Nittis’s guests included various collectors and lovers of Japanese art, such as Burty, Goncourt, Hérédia, and Jules Jacquemart (1837–1880), with whom the Italian painter shared his great passion for Japan (Carnets de comptes et des invitations des De Nittis, Piero Dini Collection, Italy).

Distinctions

De Nittis was made Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1878, the year in which he took part in the Salon and the Exposition Universelle, where he presented twelve pictures. He obtained various medals and awards for his activities as a painter, including a third class medal at the 1876 Salon and a first-class medal at the 1878 Salon. In 1878, he was also made Commander of the Royal Order of the Crownof Italy by the Italian Ministry of Public Instruction. In 1879, he became an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 44–45).

The collection

Giuseppe De Nittis’s post-death inventory, drawn up on 16, 17, and 19 September 1884, is an essential source for the study of his collection. The artist was interested in the works of his contemporaries, in particular the Impressionist painters, whose work he exhibited in the gallery of his studio on the Rue Viète, as well as his own works and screens, and Japanese scrolls (AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XII/1361). Mention is made in the inventory of a landscape attributed to Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), a pastel portrait of a man probably executed by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), two seascapes, a landscape, Les Dindons (1877, the Musée d’Orsay, inv. RF 1944 18) by Claude Monet (1840–1926), a ‘Woman with a Baby’ by Manet, a view of a studio by Ernest Ange Duez (1843–1896), a landscape by Rossano, three pastels, including perhaps a monotype, a picture representing Degas’s dancers, and a portrait of a woman by Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), associated by Marina Ferretti with Jeune Femme en Toilette de Nal (1879, Musée d’Orsay, RF 843, LUX 326), and bought by De Nittis in 1879 on the opening day of the exhibition of the Impressionists (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 394–395).

The hypothesis that De Nittis may have first seen Chinese or Japanese objects in several curiosity shops in Naples cannot be dismissed. However, it was probably in Paris towards the end of the 1860s that the artist’s enthusiasm for Asian art emerged; it became an all-encompassing passion, to such an extent that he became one of the most refined collectors of the times (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 138–139). An analysis of the specimens that belonged to De Nittis, recorded in his post-death inventory and in notes drafted either by himself or his wife (Carnets de comptes et des invitations des De Nittis, Collection Piero Dini, Italy), provides details about his collection of Chinese and Japanese art and the dealers from whom he purchased objects (AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XII/1361). These include Auguste Sichel (1838–1886), Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), the Maisons Mitsui, 11 Rue Saint Georges in Paris, and Farmer & Rogers, Regent Street, in London. In these documents, amongst other objects, mention is made of a large earthenware Japanese jardinière, a stoneware article, four bronze animal sculptures, a basin, and a bronze plateau, three carved wooden panels representing a dragon, two openwork wooden lamps, weapons, three boxes, a model of a lacquered wooden palanquin, panelling comprising twelve panels, a large item of black lacquered furniture, a tray, a dish heighted with gold, and set of parasols. In addition, the collection comprised seven Chinese embroideries, two items of Chinese furniture with three doors, sixty fukusa (embroidered silk squares, printed or decorated with China ink and colours), forty-five kakemono, forty-seven vases including thirty-three in bronze, six albums of watercolours, thirty-three albums of engravings, as well as three screens and five ‘panels’ (Moscatiello, M., 2011, pp. 386–401). One of these panels, representing around twenty pigeons on the coping stones of a basin on a silk support, purchased at the 1878 Exposition Universelle (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 180), can be associated with a kakemono by Watanabe Seitei 渡辺省亭(1851–1918), a young Japanese painter who lived in Paris as of 1878; it is now held in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington (inv. no. F2000.1a-d).

The objects in the De Nittis Collection were never sold at auction. Madame de Nittis, who upon her husband’s death had a large debt to settle, probably sold them one by one, as necessary.

In 1883, De Nittis presented twenty-seven of his fukusa at the retrospective exhibition of Japanese art held in the Galerie Georges Petit, 8 Rue de Sèze, by Louis Gonse (1846–1921) who, in his book devoted to Nippon art (L’Art Japonais, 1883) illustrated four specimens. In the chapter devoted to textiles, referring to the fukusa, Gonse specified: ‘The largest collection assembled is that owned by Monsieur de Nittis. By focusing his efforts on this unique series, this refined dilettante of Japanese art managed to collect more than fifty highly artistic embroidered squares’ (Gonse, L., 1883, Vol. II, p. 237). Other experts at the time, including Burty, Edmond de Goncourt, and Ary Renan (1857–1900), often praised the objects in the Italian painter’s Japanese collection. Although De Nittis began to take an interest in Japan in 1869, the year he created his first Japanese-inspired work, the artist focused on producing ‘Japanese’ works around 1880, after his encounter with Watanabe Seitei. He purchased the work by the Japanese artist, who had remained faithful to the pictorial traditions of his country, specifically to study its techniques. De Nittis did not restrict himself to representing the themes or decorative motifs borrowed from Oriental iconography, or the reproduction of Japanese objects in his works. His passion for Japanese art led him to imitate specific technical processes using materials usually used in Asian art, thereby creating works that made him unique in the framework of studies devoted to japonisme (Moscatiello, M., 2011, p. 249).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne