MIGEON Gaston (EN)

Biographical article

Gaston Migeon, a discreet collector and a curator celebrated by his peers, is known for his exceptional role in the Musée du Louvre, where most of his career was spent. He is now undeniably considered as the person who introduced the Islamic arts—which he designated as ‘Muslim’ at the time—and those of China and Japan to the most famous of French museums.

Gaston Migeon’s education, training, and career in the Musée du Louvre

Gustave Achille Gaston Migeon was born on 25 May 1861 in Vincennes in the home of his parents, Nicolas Gustave Migeon and Éléonore Dorothée Aucouteau, at 68, Rue de Fontenay (AD 94, 1 NUM/VINCENNES 72). Having graduated in law, he became attaché in 1888 to the cabinet of the French Minister of Public Instruction, Édouard Lockroy (1840–1913), and was subsequently appointed librarian and secretary of the École du Louvre in April 1889 (AN, LH/1873/15). Four years later, he was appointed as a conservation assistant in the Louvre’s recently established Département des Objets d’Art. The department was directed at the time by the curator Émile Molinier (1857–1906). In 1900, Gaston Migeon was appointed assistant curator in the same department, and then directed it after Molinier’s departure in 1902. In doing so he was pursuing the traditional career of museum curators during this period, who were often promoted in their department. However, his initial training was different from the more traditional training courses in the École des Chartes and those of Athens and Rome (Masson, G. in Bresc-Bautier G., 2016, Vol. III, p. 73). It seems that he was largely self-taught, as evoked by his former colleague in the Département des Antiquités Orientales, Edmond Pottier (1855–1934), in the necrology he devoted to him, in which he paid tribute to his ‘strength of character’ (Pottier, E., 1930, pp. 309–310).

Migeon’s career in the French Ministry of Public Instruction, and then within French national museums, was rewarded by many distinctions: made an Officier de l’Académie in 1889, he was made an Officier de l’Instruction Publique in 1895, then Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in August 1900. The latter award was based on a report from the Minister of Commerce during the 1900 Exposition Universelle. During this event, he participated in the organisation of the Exposition Rétrospective de l’Art Français in the Petit Palais, to which he was assigned as a deputy in the Service des Beaux-Arts (department of fine arts). He was made an Officier in October 1921 (AN, LH/1873/15). He left the Musée du Louvre in 1923 after more than thirty years of service and was awarded the distinction of ‘honorary director of national museums’ (AN, LH/1873/15, Koechlin, R., 1931c, p. 18). He remained in contact with the Louvre until his death, and, as of 1 February 1926, was a member, in particular, of the Conseil Artistique des Musées Nationaux (AN, 2015015/112, p. 362). He passed away in his home at 5, Rue Puvis-de-Chavannes in Paris, on 29 October 1930, at the age of sixty-nine (AP, 17D242, certificate no. 2073).

Gaston Migeon’s role in the Département des Objets d’art was prolific, to such an extent that he is now credited as being an ‘inventor’ of the Département des Arts de l’Islam (Makariou, S. in Bresc-Bautier, G., 2016, Vol. III, p. 103) and as the person responsible for creating the first rooms devoted to the Far-Eastern arts in the museum (Schwartz-Arenales, L., 2015, p. 42, Privat-Savigny, M.-A., ‘Migeon, Gaston’). He was interested in all the subjects associated with his activity as a curator and distinguished himself in the fields of European, Eastern, and Far-Eastern objets d’art, via its enrichment and his management of the collections, his writings, and his teaching. According to Laure Schwartz-Arenales, ‘this conjunction of curiosities and knowledge is without doubt (…) one of the most captivating traits of Migeon’s oeuvre and thinking’ (Schwartz-Arenales, L., 2015, p. 52). A tireless worker, he travelled widely, most of the time on behalf of the museum. For example, he requested to go on a mission to London in 1894 in order to ‘compare the Persian and Far-Eastern collections at the British Museum and South Kensington Museum with our similar collections in the Musée du Louvre’. He went to London in 1910 with a colleague from the Département, Carle Dreyfus (1875–1952), to Saint-Petersburg in 1913, accompanied on this occasion by Jean-Joseph Marquet de Vasselot (1871–1946), and to Vienna (AN, 20150497/178, file 268; Pottier, E., 1930, p. 310). Earlier on in his life he had travelled to Algeria with the painter Étienne Dinet (1861–1929), and then to Egypt with Charles Gillot (1853–1903) and Raymond Koechlin (1860–1931), and also to Palestine, Syria, and Asia Minor (Koechlin, R., 1931c, p. 15; Silverman W., 2018, pp. 68, 74, and 322). It is also worth noting—because it was unique for a French curator at the beginning of the twentieth century—that he went to Japan in autumn 1906 and stayed there for several months.

A major figure in the world of arts and museums

Gaston Migeon had many personal links and friendships with major figures in the world of art and curiosity at the end of the nineteenth century and the first thirty years of the following century. He was, in particular, well known by artists and collectors of Japanese art. He was a friend of the jeweller Henri Vever (1854–1942), the engraver Prosper-Alphonse Isaac (1858–1924), the engraver and printer Charles Gillot, and the collector Raymond Koechlin, who dedicated his Souvenirs to him (Koechlin, R., 1930). Passionate about Japanese art and born between 1853 and 1861, their activities succeeded those of two generations of French specialists of Japan, of whom Migeon was severely critical (Collection Ch. Gillot, 1904, p. VII; Migeon, G., 1924, p. 237). Hence, he assessed their taste and knowledge in the light of a return to an older Japanese art that began at the 1900 Exposition Universelle and the development of studies devoted to the subject. Along with Vever, Koechlin, Gillot, and Isaac, Gaston Migeon was part of the Amis de l’Art Japonais, a society founded by Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) in 1892 and taken over by Vever between 1906 and 1914. Migeon attended the very first dinner held by the Société, accompanied, in particular, by Edmond de Goncourt, Félix Régamey, and Hayashi Tadamasa (Haberschill, L. in Quette 2018, p. 100). His exchanges with the other specialists on Japan were not restricted to the events devoted to discussions about art and the presentation of selected objects from their collections. In his correspondence, Henri Vever mentioned other encounters, in particular, in his workshop (Silverman, W., 1898, p. 155, 167). The correspondence of Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906) mentioned the exchanges between the Japanese dealer and the museum curator, with the latter describing the acquisitions he wished to make for the Louvre and also asking the former’s opinion about certain articles (Koyama-Richard, B., 2001, p. 203). While attesting to the situation of these collectors in France in 1885, whom he knew, Migeon also noted the disappearance of major collections of Japanese art, dispersed after sales, for which he often drafted the catalogue prefaces (Migeon, G., 1924, pp. 236–237).

Some of these connoisseurs of Japanese art enriched the collection of Far-Eastern arts in the Louvre. Migeon was also in touch with the most important collectors of the time, such as the members of the Rothschild family, with whom he corresponded about Islamic and Japanese objets d’art (Prevost-Marcilhacy, P., 2016, Vol. II, p. 108, 186 and 216). We also know that he was very close to the Marquise Arconati-Visconti (1840–1923) [BNF, NAF 15647.XIV, FF 176]. Migeon was also active in the debates over ideas and exchanges about the private collections of his time. A friend of Koechlin, he was also in touch with other figures in the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, whose managing board he was a member of until 1921 (Prévost-Marcilhacy, P., 2016, Vol. II, p. 186).

Migeon, a promotor of Chinese and Japanese arts

‘G. Migeon’s oeuvre is the fruit of this double and considerable effort: he has left behind books that initiate the reader about science, and a fine museum where one can study the originals.’ (Pottier, E., 1930, p. 309) In the field of Chinese and Japanese arts—like that of the Islamic arts—, Migeon’s name was often cited and his contemporaries regularly highlighted his devotion and dynamism. In addition to his excellent knowledge of the various private collections and his activities with collectors, he was also a formidable promoter of the Far-Eastern arts through the presentation of his collections in the museum, the publication of many works on the subject, and his teaching at the École du Louvre.

The accounts written by Migeon’s first biographers, such as Koechlin, who was one of his closest friends (Koechlin, R., 1930, 1931c), represented him as the initiator of the collections of Far-eastern arts in the Louvre (Koechlin, R., 1931c, p. 5). This frequently repeated claim has now been re-evaluated in the light of new research into the actions of Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929) in the field of the arts (Séguéla, M., 2014a, 2014b) and his involvement alongside critics such as Roger Marx (1859–1913) and Gustave Geffroy (1855–1926) with the introduction of the Japanese arts into the Louvre. This commitment resulted in the purchase of two Japanese sculptures from the dealer Siegfried Bing in 1891 (‘Au Musée du Louvre’, 1907).

The French national museum archives distinguish between Migeon’s active participation in the establishment of the collections of Far-Eastern art and his dynamic involvement in the enrichment of the collections. He often solicited collectors and also approached the Conseil Artistique des Musées Nationaux to make fresh acquisitions (Koechlin, R., 1930, pp. 103–104 and 1914, pp. 19–20). Henri Vever’s correspondence highlights the strategies implemented to enrich the collections. In addition to his friendships with most of the first donators of the new section, such as Vever (Possémé, E and Atiken, G., 1988), Migeon made the most of his position as curator to negotiate favourable prices with the dealers (Silverman, W., 2018, p. 103).

This first group, comprising two Japanese sculptures bought from Bing (MNAAG, inv. nos. EO1 and EO2), was complemented by a certain number of donated objects and those already present in the museum, which were dispersed as the various departments were enriched. The arrival of the collection of Chinese porcelain owned by Ernest Grandidier (1833–1912) in 1894, followed by that of Japanese ceramics in 1895, considerably enriched the recently established Far-Eastern section. At the beginning, the collections mainly comprised Japanese prints and objets d’art, and were subsequently complemented by two ensembles donated by Grandidier and placed in a room adjacent to those that housed the latter on the mezzanine of the Grande Galerie (AN, 20144787/13). Thereafter, the collection constantly expanded and was placed on the mezzanine. As of 1912, the eight adjoining rooms devoted to the Grandidier Collections were filled with the objects brought back from the missions of Alfred Foucher (1895–1897), Édouard Chavannes (1906–1907), and Paul Pelliot (1906–1907), followed by two new galleries where Chinese and Japanese objets d’art were exhibited (Guide Joanne, 1912, pp. 65–66). This refurbishment, undertaken during Migeon’s stewardship brought together most of the Far-Eastern collections located on the mezzanine: the objects brought back by Foucher, which were placed with the Antiques, those of Pelliot, which were placed on the ground floor of the museum, facing the Tuileries, and all the objects, which due to a lack of space, had been placed in the storerooms (Koechlin, R., 1912, p. 44). These areas were created in the space occupied by the former apartment of the director of the Louvre, Théophile Homolle (1848–1925). They were nor really suitable exhibition areas: like the rooms devoted to the Grandidier Collection, these ‘cul-de-sac’ spaces were vaulted and dark (AN, 201444794/32, letterfrom the Directeur des Musées Nationaux and the École du Louvre to the Under-Secretary of State for the Fine Arts, dated 21 March 1911).

Between 1905 and 1910, Migeon sought to enrich and complete the collections of ancient objects (Migeon, G., 1912a, 1912b; Michel, A. and Migeon, G., 1912, pp. 163–167). He set out to acquire objects that had both an ‘archaeological and artistic’ interest (Migeon, G., 1912a, p. 79). At the time, he realised that the collection was missing many articles that were ‘difficult to find for certain periods’ (Michel, A. and Migeon, G., 1912, p. 165). He regretted the absence in the Camondo bequest of 1911, of ‘stone sculpture from the ancient Han, Wei, and Tang dynasties; we are aware of authentic masterpieces imported into France over the last four or five years’ (Vitry, P., 1914, p. 84).

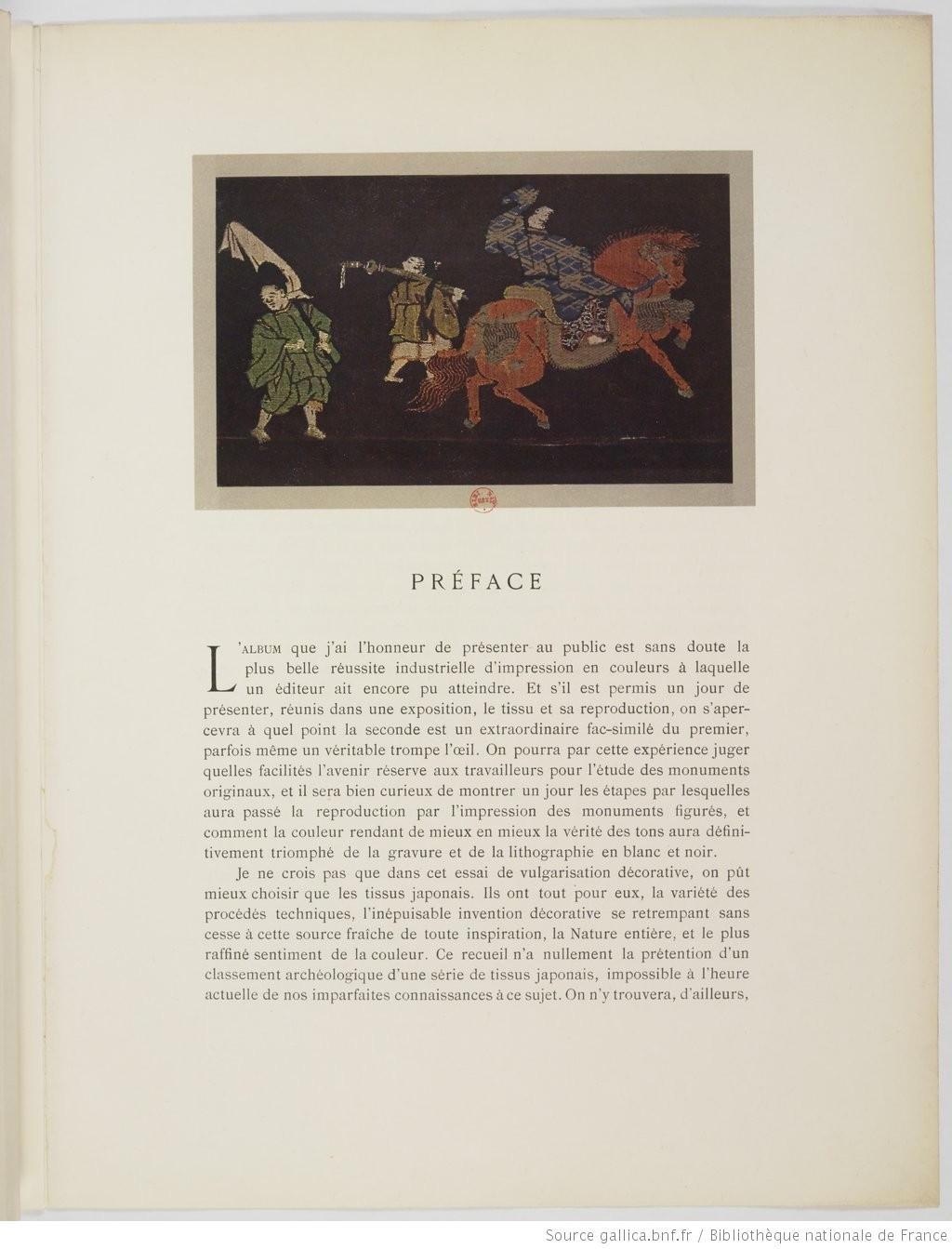

In fact, the name Migeon is associated with several dozen works, articles, and prefaces of sales catalogues and catalogues of collections, in all the fields covered by his department (Privat-Savigny, A.-M., ‘Gaston Migeon’). With regard to Chinese and Japanese arts, he devoted several articles to them, particularly in the Revue de l’art ancien et moderne (Migeon, G., 1924, 1926, and 1928). The publications that featured the museum’s collections (Migeon, G., 1912a, 1912b, 1925, 1927 and 1929) were complemented by articles about more specific subjects, in particular, textiles (Migeon, G., 1905a), prints (Migeon, G., 1914b), and museums of Asian arts (Migeon, G., 1897, 1928). Migeon’s career coincided with a pivotal period in the development of knowledge about these arts in France. Their study and promotion by diplomats and collectors in the second half of the nineteenth century was followed by an awareness of their antiquity, with, in particular, the discovery of the ancient arts of Japan at the 1900 Exposition Universelle. With regard to China, the missions of Pelliot and Chavannes and the many excavations of ancient objects on Chinse territory reflected the taste of the collectors for the periods preceding the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644); numerous works dating from these periods could be found in the capital. Migeon was always careful when writing about the history of Chinese and Japanese arts, as he saw knowledge about the subject as ‘provisional’ (Migeon, G., 1905b, foreword, not specified). Concerning Chinese painting, he declared: ‘Our critics are hesitant and undecided before the paintings, even when they are highly moving; for they leave us with the bitter sentiment of scepticism and the discouragement of our inability to understand them’ (‘Observations sur la peinture chinoise’, 1926, p. 201), adding that it was ‘such a formidable and mysterious’ subject (p. 205). He systematically distanced himself from theorisations and syntheses (Migeon, G., 1905a, p. 89, 1908 pp. 2–3, Verneuil M., 1908, p. 7), showing little initiative in this field. His book devoted to masterpieces of Japanese art (1905) attests to his stance. The publication is a very large-format work, which is entirely devoted to the reproduction of the works. He himself described his book as an ‘album of documents of Japanese art’ and sought to publish ‘previously unseen’ documents. He declared that ‘the text has been reduced to a minimum: the images alone are eloquent’ (Migeon, G., 1905b, foreword, not specified). The same applied, for example, to his Art Japonais (1927), in which the object descriptions and works were placed directly after very short introductory texts devoted to each of the fields addressed.

In 1903, Migeon took over from Molinier at the École du Louvre and ran the courses associated with the Département des Objets d’Art. He devoted his courses to Chinese and Japanese arts in 1907 and 1908, after his trip to Japan (Marquet de Vasselot, J.-J., 1932, p. 88). In the autumn of 1906, he did in fact set off for the archipelago via America, where he stayed with Ernest F. Fenollosa (1853–1908) at the home of Charles L. Freer (Fenollosa, E., 1913, p. X). The famous historian of Japanese art, who lived in Japan for many years and completed several missions for the Japanese government, gave him letters of introduction that enabled him to access many temples and sites (Fenollosa, E., 1913, p. X). Migeon published an account of his travels in 1908. Having been previously published in the form of letters in the press, he intended his book to be an account of his ‘impressions’ (Migeon, G., 1908, p. 11). From the mission he had been entrusted with by the Under-Secretary of State for the Fine Arts, Étienne Dujardin-Beaumertz (‘Au Musée du Louvre’, 1907), he brought back several ancient works for the Louvre, which were then considered as ‘revelations, whose equivalents, if they existed in other European museums, were only exceptional, and even then precious and rare exceptions’ (‘Au Musée du Louvre’, 1907).

Migeon resumed his focus on the Far-Eastern arts in his courses in 1919 and 1920 (Marquet de Vasselot, J.-J., 1932, p. 89). The years devoted to the arts of China and Japan made Migeon into a veritable ‘precursor’ for Marquet de Vasselot, who highlighted the novelty of this field of learning in the École du Louvre. One of Migeon’s former pupils affectionately described him as a teacher who was passionate and deeply involved in his research, and who was curious and had great artistic sensibility (Jean, R., 1932, p. 91). This quality, along with his love of Eastern and Far-Eastern arts, in particular those of Japan, was perhaps linked to his ancestors, as the Migeon family had been famous cabinetmakers in eighteenth-century Paris (Koechlin, R., 1931c, p. 4; Mouquin, S., 2001; Schwartz-Arenales L., 2009 and 2015).

The collection

Accounts of Migeon’s practices as a collector are rare. In 1898, Vever recounted that he examined at Madame Migeon’s residence in Vincennes, her son’s collections, which according to him were too limited but interesting (Silverman, W., 2018, p. 129). Koechlin even declared that ‘Monsieur Migeon was not a collector, and if he had had the soul of one, he would no doubt have considered that his duty as a curator in the Louvre prevented him from competing with the antique dealers or in the sales in the Département he was in charge of; but he liked to embellish and adorn his home with works of art in his taste, and as he had begun to acquire objects for his collection very early on and continued doing so until late in life, he eventually had a very fine collection.’ (Koechlin, R., 1931b, p. 21).

The contents of his private collection, which has now been dispersed, is known through two sales (in 1911 and 1924) and a post-death sale (1931), as well as through the many generous donations he made to the Louvre. His collections were enriched in three fields: drawing and painting, in particular the Impressionists, the Islamic arts, and those of China and Japan.

A close examination of the inventory of Far-Eastern collections in the Louvre (‘inventory EO’) highlights the curator’s various donations. In 1894, he donated to the museum a print attributed to Hiroshige (inv. no. EO268). In 1907–1908, he donated a collection of Korean and Japanese stoneware brought back from his mission in Japan (inv. no. EO900-925). The objects he acquired during his trip in 1906, paid for by the museum, had been recorded in the inventory a little earlier (inv. nos. EO829–EO856). In 1909, he participated with the dealer Léon Wannieck (1875–1931) in the funding of ‘archaic’ Chinese ceramics (inv. nos. EO931–EO957) along with Atherton Curtis (1863–1943), Jacques Doucet (1853–1929), Ernest Grandidier, Raymond Koechlin, and Alexis Rouart (1839–1911). He made a new collective donation in 1911, transferring eight prints to the museum (inv. nos. EO1041–1048), along with Koechlin and Isaac. He donated several Chinese bronzes and other metal objects the same year (inv. nos. EO1464–1499), as well as a collection of ‘compte-gouttes’, or water droppers (inv. nos. EO1500–1517). In 1931, he bequeathed three inrō (inv. nos. EO 2880–2882), a round lacquered box (inv. no. EO2883), and a bronze statuette dating from the Ming Dynasty (inv. no. EO2884). His generosity was not limited to the Far-Eastern arts: his bequest comprised, for example, several Impressionist works and a bronze Muslim mortier (AN, 20150157/113 and 20150157/41), and several works were set aside for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

In 1911, Gaston Migeon sold Chinese and Japanese objects in his collection. In the sale catalogue—perhaps drafted by Marcel Bing (1875–1920), who was the expert—there were Japanese wooden sculptures, six Chinese and Japanese bronzes, in particular, from the Ming Dynasty, Chinese and Japanese incense burners, ‘compte-gouttes’ (‘water droppers’), several Chinese and Japanese vases, a seventeenth-century bronze Chinese cloisonné enamel, seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century Japanese stoneware, in particular, raku, Japanese sabre guards, handles of knives with their blades, seventeenth- and nineteenth-century Japanese lacquered objects, inrō, netsuke, and Japanese paintings and prints. His second sale, this time appraised by André Portier (18 ?–1963), was held in 1924. The auction of Chinese and Japanese objects was held on 22 and 23 February. The auction primarily concerned Chinese bronzes (34 lots) and Japanese bronzes (92 lots), lacquered objects, netsuke, several items of Chinese porcelain, and several ceramic objects from Japan, as well as tsuba, several prints, a kogo (incense container), a hardstone fibula, a set of wickerwork objects, and Japanese and Chinese fabrics, in particular, from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The post-death sale was more diverse and comprised 848 objects. With regard to the Far-Eastern objects, there were 421 items of Japanese art (prints, watercolours, drawings, screens, bags, paintings, lacquers, bronzes, ceramics, fabrics, books, masks, furniture, vases, and various other objects) and only twenty-seven items of Chinese art (bronzes, ceramics, fabrics, and embroideries) (Oudin, H., 1994, p. 32).

As in his writings, Migeon showed a clear preference for Japanese art in his collections. They were modest, as was his fortune (Oudin, H., 1994, p. 32). He purchased his objects, in particular, from contemporary Parisian dealers such as Hayashi, and perhaps he did not give all the objects brought back from Japan to the Louvre, which suggests that certain objects that were auctioned were acquired in Japan. He seems to have rigorously selected the few objects in his collections, as Vever mentioned. In fact, in 1898, Migeon declared: ‘It is not indispensable for a collection to be large, but it must be well selected, and each object in it, even if it does not evoke a profound artistic emotion, at least provides some information or a serious element of curiosity’ (Migeon, G., 1898, p. 256). Koechlin echoed this, and considered that Migeon’s donations to the Louvre were ‘modest, but always pertinent’ (Koechlin, R., 1931b, p. 23). Very interested in the prints, he acquired, in particular, ‘primitive’ works, which he exhibited in February 1909 in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (Vignier, C., and Koechlin, R., 1909). His collection of small Chinese bronzes, in particular from the Ming Dynasty, was also remarkable (Migeon, G., 1929, p. III; Vitry, P., 1914, p. 84; Koechlin, R., article 1931).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne