LEPRINCE-RINGUET Félix (EN)

Biographical Article

Félix Leprince-Ringuet was the son of merchant Edmond Adrien Leprince-Ringuet and Marine Anne Michelle Paillard, without profession. His marriage to Renée Stourm marked the alliance of two notable families. Renée Stourm was the daughter of René Stourm (1837-1917), who was secretary in perpetuity of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques, and Louise Stourm, who was born on March 29, 1900 in the church of Saint-Thomas of Aquin, and whose maiden name was Lefébure de Fourcy. From then on, he lived in Aube and exercised his electoral rights in Bercenay-en-Othe, where his in-laws resided. Summers were spent at the Stourm residence. Welcomed into the intimate community of Aube, he was elected on January 15, 1926 as a life member of the Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts of the Department of Aube. In 1933, he became president of the Cercle de l'Aube in Paris. Félix Leprince-Ringuet led a brilliant career within the corps of mining engineers and approached the issue of coal mining from various perspectives.

Education

He studied at the collège Stanislas, where he received the Lagarde Prize in special mathematics in 1892 (L'Univers, 1892, p. 3). He continued his training at the École polytechnique in Paris, from which he graduated with a degree in science in 1894. The following year, he became a student of mining engineering and completed his military service, with the rank of second lieutenant of artillery, from October 1894 to October 1895.

Geological Surveys in China: First Mission

As an engineering student, he undertook numerous study trips to Belgium, Germany, Russia, and Transcaucasia in 1897. The following year, he was assigned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Théophile Delcassé (1852-1923) sent him to China on a mission for Crédit Lyonnais. Assisted by Louis Feydel, a civil engineer from the École des Mines, he studied the different fields of activity offered to European companies. His studies led him in the footsteps of the German geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905). The objectives of his mission in China turned out to be quite broad. It was also a matter of studying the two railway lines conceded by the Chinese government: the line of Beijing (北京)-Hankou (漢口) [current Wuhan (武漢)] and that of Zhengding (正定)-Taiyuan (太原), to carry out prospecting with a view to their possible ramification, and to examine the potential resources of this zone. The country was accessible to foreigners, but a certain number of events came to thwart the installation of potential investors and compromised the otherwise promising outlets for trade. These were the beginnings of the Boxer Uprising. Rumours circulated about the poisoning of the Emperor and target Europeans. Xenophobia was in the air.

Scientific Travel and Sporting Pleasure

Driven by a taste for mountaineering, he climbed Mount Hua (華), a sacred mountain located in Shanxi (山西), which rises to 1,623 meters above sea level. He reported on this ascent in the Annuaire du Club alpin français (1900), of which he was a member. The return trip was via Japan, British Columbia, and Canada, where he took advantage of his passage to climb Mount Sir Donald, culminating at 3,284 m, representing twenty hours of hiking and climbing. He published the story in the New York Times of August 3, 1899. He also recounted his excursion to the Caucasus and his ascent of Mount Ararat in front of the passionate audience of the Club alpin français (1902).

On the occasion of a trip among alumni of the École des Mines and Ponts et Chaussées, he visited Switzerland in 1903 and passed by the Col du Simplon. In 1911, he was sent on a mission to the mountainous region of Transbaikalia, an oblast of Imperial Russia located in the extension of Lake Baikal in northern Mongolia. There, he met the Dalai Lama by chance. In 1921, he was in charge of a mission in Spain.

In 1929, he took advantage of his presence in Africa to make an excursion to the Belgian Congo, to the Nyiragongo volcano, located in the Great Rift Valley. He planned to climb Kilimanjaro, but foot pain makes him abandon his plan. He returned to Marseille, via the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal. His account in the Annales des Mines (1931) describes resources of what is now Zimbabwe: the Wankie [now Hwange] coalfield, the Railway Block chromite mine in the Selukwe region, the asbestos mines of Shabani [now Zvishavane], and the mica mines, as well as the South African gold deposits and their operating conditions.

Following a trip to the United States, Félix Leprince-Ringuet was admitted to the Société de géographie de Paris in 1931. The concept of geology evolved to become a multidisciplinary geography.

Electricity and Coal Mining

In 1899, he graduated as an engineer from the Corps des Mines. He worked successively in Alais, Amiens, Béthune, and Arras. He participated in the Congress of Electricity in Marseille in 1908 and took part in a mission the following year to Germany and England to study central stations for the production and remote supply of electricity. In 1910, he more specifically studied electricity in the coal mines in these two countries. He participated in the Congress of the Mineral Industry in Düsseldorf, preceding his mining research in Eastern Siberia. In 1911, Félix Leprince-Ringuet became Chief Engineer of Mines. The mineralogical district of Nancy, then that of Versailles were successively placed under his direction. After the war, he will be in charge of that of Paris. In 1913, he studied the western saltworks. From 1912 to 1920, he held the position of president of the eastern district of the Mineral Industry Company, then of that of Paris from 1936 to 1943. By decree of January 8, 1913, he was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Awareness of the Danger of Mines; Matter of the Protection of Minors

Undoubtedly tested by the disaster of Courrières, which he attended when he had only recently graduated, he would not cease throughout his career to deepen the question of safety in the mines. At least, this is what his peers noted in the summary notice to support his promotion file to the rank of Commandeur of the Légion d’honneur (AN, 19800035/177/22814). Félix Leprince-Ringuet was aware of the dangers that mining presented to labourers working underground. He played an important role in the rescue of the Courrières mines in Billy-Montigny in 1906, even though they did not appear in his sub-district. On March 10, 1906, a firedamp explosion killed 1,099 miners. The explosion had been preceded a few days earlier by a first fire, which created a climate of tension among the miners. After the disaster, Félix Leprince-Ringuet, a control engineer, with his brother René, an engineer from the Compagnie de Courrières, actively led the search to find any survivors. They descended into the shafts and travelled the tracks. This disaster had a profound effect on the consciences of many people, and thereafter Félix Leprince-Ringuet studied the English example of managing such disasters. He then published a work on heat in mines and the flammability of firedamp, which he presented in 1907 to the Académie des Sciences. In 1919, he studied the collective institutions of the Ruhr, and delved into the question of security and progress in the field of mining. At this time, he also received the Montyon prize rewarding work in "unhealthy arts". The Académie des Sciences thus saluted the initiatives and studies undertaken by Félix Leprince-Ringuet on the means of protecting workers exposed to the dangers of mining excavations. In 1936, he was appointed vice-president of the Commission des recherches scientifiques on the use of firedamps and explosives in mines.

Mobilisation

In 1914, he was mobilised into the army. He was appointed squadron leader of the northwest sector of Toul, to be commander of the center for the supply of automotive equipment (Centre d’approvisionnement de matériel automobile / CAMA) in Vincennes from October 1, 1915 to August 26, 1916. He received recognition from the Undersecretary of State of Artillery and Ammunition for services rendered. He was then assigned to the Boulogne-sur-Mer artillery park to direct the mining department, in the Northern Territory and Pas-de-Calais, which was still protected from the German invasion. The excellent results obtained would once again earn him recognition, this time from the Ministry of Public Works, on January 13, 1921. He increased the monthly production of the non-destroyed mines from 650,000 (1913) to 700,000 tons (October 1916), to 1,000,000 tons in August 1917, and put an end to coal traffic in the ports (AN, 19800035/177/22814). On November 11, 1918, he was assigned to the Ministry of Armaments, within the mining service of Nancy, as Lieutenant Colonel.

From 1918 to 1919, he played an important role in the rehabilitation of the iron mines in the Briey basin. He participated in the creation of the école des Mines et de la Métallurgie of Nancy. From 1919 to 1936, he was appointed administrator of the Mines of Tharsis.

The Ministry of Public Works called on him for the assessment of war damages on the mines: he was appointed central administrative agent, delegate to the reparations commission. On February 1923, he was elevated to the rank of Officier of the Légion d’honneur by decree of the Minister of Liberated Regions for his actions during the war.

Expertise Requested

Félix Leprince-Ringuet held the role of technical adviser to the arbitration commission for Moroccan mining disputes from 1920 to 1923.

On January 16, 1924, he was promoted to Inspector General of Mines, to the first division of the General Inspectorate (Nord and Pas-de-Calais), a status which confirmed his acquired expertise in this field.

The same year, he studied the exploitation of phosphates from Morocco and the Austrian saltworks. At the invitation of Alfred Rudolf Zimmermann (1869-1939), Commissioner General of the League of Nations, Leprince-Ringuet was asked to study the budget and operation of the Austrian saltworks in Vienna and give his opinion as an expert on the organisation and performance of this important state monopoly (Le Temps, 1924, p. 2).

Delegated by the Ministry of Public Works, in 1929 he attended the International Geological Congress in Pretoria. The development of mining operations made it necessary to establish the stratigraphy of subequatorial Africa. The congress thus led to the creation of a sub-commission of African geological surveys. Félix Leprince-Ringuet thus studied the geological constitution and the mining industry in Southern Rhodesia, in the extension of the two consecutive missions carried out by the chief engineer of the Mines, Lucien Dumas (1894-1984) in 1924 and 1925. He also took advantage of his presence in Africa to travel to Kenya via the Transvaal, visiting the diamond mines, Lake Victoria, the Upper Nile Valley, and the city of Mombasa. He was a delegate to the World Energy Congress in Denmark, and continued his investigations in Sweden, Norway and Finland.

In 1933, he was appointed by the ministry as the representative of Algeria on the Council of Ouenza. Founded in April 1914, the Société de l'Ouenza operated iron mines in the south of Constantine. Historian Samir Saul considers the Djebel Ouenza site "the most important in North Africa" (2016, p. 527). Leprince-Ringuet resigned in 1939, asserting his refusal to exchange his functions for those of consulting engineer of Ouenza (AN, 19800035/177/22814).

In 1934, he attended the Mining Industry Congress in Liège. In 1936, he represented France at the session of the International Statistical Institute in Athens. He went as far as Yugoslavia to visit a number of farms.

Leprince-Ringuet took part in the creation of the Mining Documentation Bureau in 1936. He became a member of the Central Commission for Steam Engines and the High Commission for Inventions (AN, 19800035/177/22814). From 1942 to 1943, he participated in the Colonial Mining Regulations Commission at the Ministry of the Colonies.

From 1912, Félix Leprince-Ringuet was a member of the Society for Economic Studies. He became a member, then president of the commission responsible for examining and coordinating statistical information on the mining industry and steam engines, under the aegis of the Ministry of Public Works. He took part in the High Council for Statistics and became President of the Paris Statistical Society from 1942 to 1945.

From 1936 to 1940, he held the position of director of the École nationale supérieure des Mines. He left his post in February, a few months before the occupation of part of the school by the Luftwaffe. On July 14, 1939, he retired.

In support of their request, his recommenders for the rank of Commandeur of the Légion d’honneur underscored his contributions to the modernisation of programmes and teaching methods, as well as in the construction of new chemistry laboratories ( AN, 19800035/177/22814).

Suffering from a serious illness, he had both his legs amputated in the 1950s. The title of Commandeur of the Légion d’honneur was conferred on him on October 27, 1953, by decree of the Ministry of Public Works, in recognition of his many services rendered.

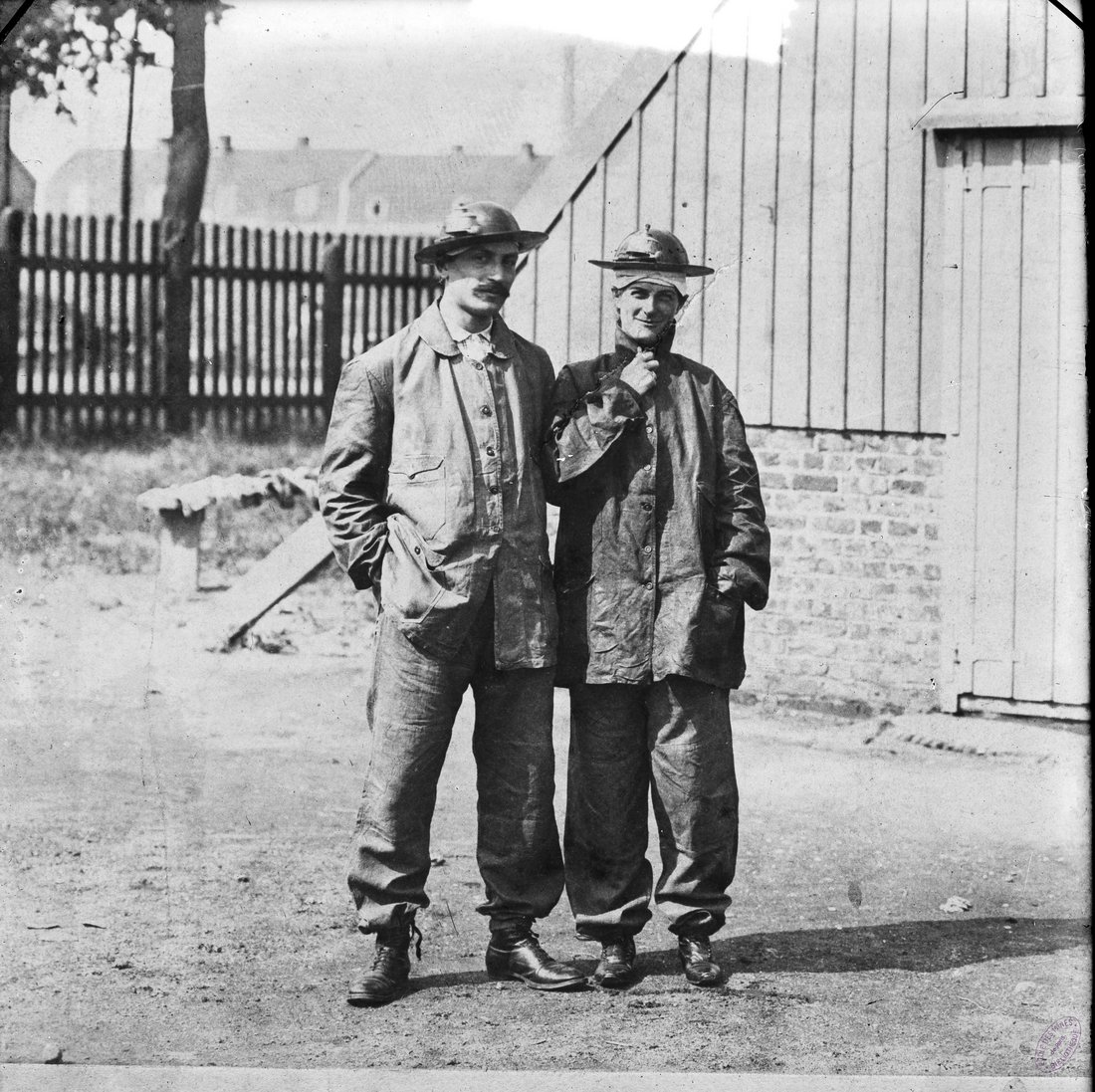

Félix Leprince-Ringuet

1901

MINES ParisTech

Photographie

13×18

MG_6190

Collection Felix Leprince Ringuet

© Bibliothèque Mines Paris - PSL

https://www.bib.minesparis.psl.eu/

The Collection

The Félix Leprince-Ringuet Collection at the École nationale supérieure des Mines

The travel notes, photographs and archives of the mining engineer were transferred in December 2010 to the school where he had been the director, by his 23 beneficiaries. Bruno Turquet, grandson of Félix Leprince-Ringuet, gathered the documents and allowed them to be organised formally beforehand.

It turned out that the photographic plates had not always been kept in good conditions. Some had become unusable. Others were of no particular interest. It was thus necessary to make a selection from the initial collection and recondition the proofs (Turquet B., 2016, p. 15).

A process of identifying the photographs followed. Bruno Turquet returned to the system of annotation system favoured by Félix Leprince-Ringuet, who carried out a rather meticulous report of the shots taken in the field in an A4 notebook and on individual sheets. The photographer noted directly on the support, on the gelatin, in the interstice of the two stereoscopic images. He could also number the negative, in a corner of the plate (Turquet B., 2016, p. 15). Some photographs, however, remain untitled.

In collaboration with the Centre de recherche en informatique at Mines Paris-PSL, a project of digitising the glass plates was undertaken, headed by photographer Benoît Pin, with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II camera (Turquet B., 2016). The images then underwent specific processing to make them easier to read on a computer screen. The database, currently being indexed, currently respects the titles given by the engineer to the storage boxes in which the photographs were found. The iconographic database is hosted by the website annales.org, available at this address: leprince-ringuet.annales.org. One criticism that might be directed toward this work is to have hidden the photographic object, keeping only the image represented by the photograph. The catalogue of the collection fills this gap by showing the stereoscopic plates.

Photographs of China

Félix Leprince-Ringuet stands out as a collector of views, the collection bringing together the photographs both of the engineer and of the people close to him or encountered during his travels. He also bought photographs in the field. Some shots were made by his traveling companion, Louis Feydel; others by the missionary G. Maurice. The engineer varied the supports, and also executed some sketchy drawings. The notebooks give an account of his acquisitions and expenses during the trip, linked, among other things, to the development of in situ photographs and the acquisition of equipment. Félix Leprince-Ringuet notably bought a camera, two frames, a tripod, and a lens. He also bought glass plates. Some damage forced him to have his camera repaired, an indication that he rubbed shoulders with the photographic community of China. The notebooks turn out to be quite lapidary, and do not mention the place and the reasons for the material incident.

Félix Leprince-Ringuet worked as an amateur photographer, opting for a diversity of techniques and formats, with a marked preference for stereoscopic photography (Turquet B., 2016). The photographs were generally taken on the spot. The photographer sometimes opted for posed photography, taking up certain codes of studio photography, close to staging, when making group photographs. The collection includes a studio portrait of Father G. Maurice. Félix Leprince-Ringuet demonstrates audacity in his shots. His overhanging views and sharp framing attest to a certain originality.

"Yellow Earth", Symbol of China

Strangely, landscape photography, which was expected in this kind of mission, is not a dominant subject. Félix Leprince-Ringuet tackled various subjects and did not limit himself to his favorite field, geology. One set of photographs develops this strictly geological aspect, the gaze focusing on the geological configuration of the landscape, the outcrop of the rocks, the stratigraphy of the terrain and the methods of occupation of the space.

In the middle basin of the Yellow River in northern China, Félix Leprince-Ringuet carefully observed the "maze of loess" unfolding before his eyes in the province of Shaanxi (陝西) [1902, p. 324]. This yellow earth became the symbol of China and caught the attention of geographers Élisée and Onésime Reclus, appearing on the cover of their book L’Empire du Milieu (1902). In reality, loess is only visible in the Ordos (Mongolia), and the provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi. This region is considered by the engineer as "the cradle of China" (1901, p. 347). This "cloak of loess" "prints the country with its special character" (1901, p. 951), for Félix Leprince-Ringuet, who leaves open the question of its origin and its formation. The photographer offers the gaze the materiality of this friable rock, which marks a moving landscape. The bed of the Yellow River has evolved over time. Habitat models and cultures also come into his sights. Félix Leprince-Ringuet is interested in houses dug into the loess, which give rise to quite spectacular photographs, taken from heights and endowed with a wide depth of field.

Photographs of furnaces and smelting workshops complete the mission, in the study of mining activities. However, the author provided no further details on their operations. The workers likewise remained in the shadows. Furthermore, the concentration of heat sources and the presence of parasitic light affect the rendering of these images.

Transport and Trade in China

Several photographs show the ports of Shanghai (上海) and Hankou (漢口) bristling with a crowd of masts, where the junks clustered around the quays describe an almost harmonious disorder. The gaze lingers over the middle Yangtze basin (Chang jiang [长江]), in the province of Hubei (湖北), at the level of Wuhan, in the district of Hanyang (漢陽), place of confluence of the Yangtze and the Han漢).

The question of means of transport and caravan routes is richly documented. The photographer adopted a fleeting perspective to suggest an endless parade of carts of various goods. He did not hesitate to reduce the frame of the image and truncate the succession of vehicles in single file, suggestively evoking the off-screen. Félix Leprince-Ringuet reported on "colossal" activity in winter on the road to Shanxi (Leprince-Ringuet F., 1902, p. 325), through which transited anthracite, iron bars, lime, coal, skins of all kinds, perfume, tea, flour, and cereals. Sometimes, the gaze lingers on the rudimentary nature of the means of transport and the infrastructures in place. Transport infrastructure is also incriminated. A few photographs show the dilapidated or poorly developed nature of the network of paths and roads. Félix Leprince-Ringuet thus depicted pavement of the main Mandarin road that had been "degraded by time", "because we no longer repair anything in China, and the country is nothing more than a ruin of once grandiose works" (Leprince-Ringuet Ringuet F., 1902, p. 318). Construction sites are mentioned sporadically.

Climbing Mount Hua

The series of views of Mount Hua is a sideline to the actual exploration. The ascent does not appear in the mission program and does not appear visible in the report published in the Annales des Mines (1901) nor in the report published in the popular magazine Le Tour du Monde (1902). However, for Félix Leprince-Ringuet, this place of Taoist pilgrimage represents an "uncommon spectacle", "as one sees only in China" (1900, p. 364). We do not have views of the mountain itself. He gave a report on the ascent: arriving at the top of the mountain, his gaze focused on the tops of the steep peaks around. The relief was steep and arid; the eye was drawn to the sharp profile of the North Peak (bei feng [北峰]).

The Christian Presence

Some photographs recall the Christian presence in China. In mid-January, 1899, Félix Leprince-Ringuet stopped over at the orphanage of the Sisters of Mary Help of Christians (Marie-Auxiliatrice) in Tongyuan (通遠), in the district of Gaoling (高陵), attached to the prefecture of Xi'an (西安), in Shaanxi Province. These photographs show the buildings making up the mission and the sisters at prayer, portrayed modestly from behind. The photographer lingered on the churches encountered during his crossing of Shaanxi. The stele dating from the Tang period also held his attention. Decorated with a cross, it represented for the author the testimony of "the official recognition of Christianity in China" in the year 635 (1902, p. 354). Today, others consider the stele to be proof of the Nestorian presence in China, a doctrine rather inclined to heresiology in the early 20th century (Gernet J., 2007).

A Restricted Vision of Chinese Society

In addition to these souvenir photographs, which evoke the journey of the mission, Félix Leprince-Ringuet takes a look at small trades, port life, and means of transport. Thus, we see a mobile restaurant parked on the port of Shanghai. A woman blows on her still-hot bowl of rice. The photographer attends a pedicure session on the public highway. He captures the bustle of a shopping street in Xi'an (西安). His gaze is drawn to the stall selling false braids in Weinan (渭南). This production reveals a significant sociological dimension, even if this was not the purpose of his trip. Félix Leprince-Ringuet’s work depicts some cultural traits: he, the photographer, captures the wandering of a funeral procession in the Chinese countryside; he preserves the festive atmosphere of New Year's Day, the crowd gathered for the Lantern Festival, at the rampart of the city of Xiping (西坪), in the district of Datong (大同), in the province of Shanxi. The photographs represent the poverty of a mire of the population of Anyi (安邑), evoking people in rags sitting on the sidewalk.

The iconographic corpus presents a limited panel of Chinese society. The photographer seems to recognise this, and tries to fill these gaps by presenting the photographs of cut-out paper puppets and wooden statuettes to the reader. These figures serve as a substitute for the Chinese crowd, this "somewhat confused variety" (1902, p. 330).

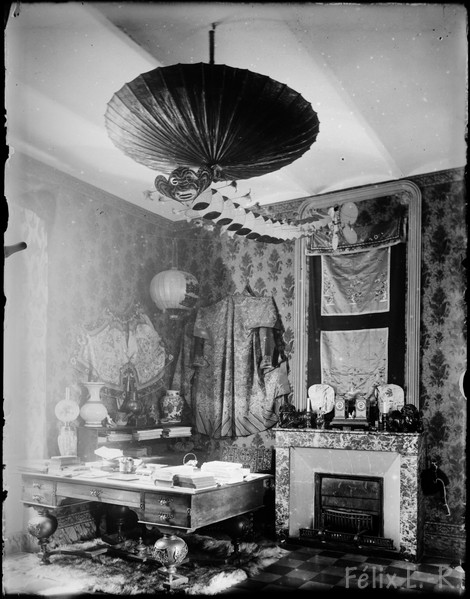

A Collector of Souvenirs: Photographs, Objects, and Photographs of Objects

Some images are anecdotal. And the photographer does not seem lacking in humour when he poses with his acolytes, seeming to emerge from a monumental sculpted vase. These photographs can be seen as memories, in the same way as the objects that were collected, whether the result of purchases or of bets; Félix Leprince-Ringuet was also a gambler.

Photographs of objects from popular culture indicate the building up of a collection of objects in addition to the collection of views. Reading the notebooks confirms the engineer's interest in Chinese art and craftsmanship, presenting the list of purchases and their distribution in the boxes to be shipped. The objects turn out to be heterogeneous in nature and of indeterminate value. Only one piece is precisely dated: this is a vase from the Kangxi (康熙) period [1654-1722; r. 1661-1722], meiping type (梅瓶). Note also the variety of materials collected – bronze, pewter, copper, porcelain. Thus, this collection includes a green mandarin dress and another in shades of blue. Additionally, one finds elements of female adornment, including a set of rings and ornaments, a woman's coiffure set, Chinese shoes, probably slippers for bound feet. There are also copper and bronze vases, cloisonné, "small bronzes" - meaning bronze statuettes? - two teapots, a set of "puppets and mannequins", probably the shadow theatre figurines represented in the photographs. The collection also includes an opium smoking kit: a number of pipes, 8 pipe cords, an opium lamp, lithographs and a set of 21 portraits, the quality of which is unknown. There is also a compass, a chess set, "Ningpo objects [Ningbo (寧波), Zhejiang (浙江)]", without any other form of precision. Peking porcelain (北京), divided into two cases, is also in the collection. Finally, boxes number 11 and 12 contain Tianjin terracotta (天津).

Photographs stored in the "China" box conjure up the Chinese interior of the Leprince-Ringuet couple's house in Alès, in the Gard, showing the objects in their context of use.

For Félix Leprince-Ringuet, travel was inseparable from the collection of information and the sharing and transmission of acquired knowledge. It provided a "baggage of memories that may be useful to others" (1902, p. 313). The photographer captured both the "charm" of picturesque landscapes, which highlights "the flavor of travel", and the factuality of landscapes, nourishing scientific documentation. The photographs communicated to Hachette for the review of the Tour du Monde were reused in the textbooks of professors Fernand Maurette (1878-1937), associate professor of history and geography, and Albert Demangeon (1872-1940), professor of economic geography at the university in Paris.

Félix Leprince-Ringuet

1900

Photographie, plaque de verre

13×18

MINES ParisTech

MG_0018

Collection Felix Leprince Ringuet

© Bibliothèque Mines Paris - PSL

https://www.bib.minesparis.psl.eu/

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne

Sommaire

- The Collection

- The Félix Leprince-Ringuet Collection at the École nationale supérieure des Mines

- Photographs of China

- "Yellow Earth", Symbol of China

- Transport and Trade in China

- Climbing Mount Hua

- The Christian Presence

- A Restricted Vision of Chinese Society

- A Collector of Souvenirs: Photographs, Objects, and Photographs of Objects

- The Collection

- The Félix Leprince-Ringuet Collection at the École nationale supérieure des Mines

- Photographs of China

- "Yellow Earth", Symbol of China

- Transport and Trade in China

- Climbing Mount Hua

- The Christian Presence

- A Restricted Vision of Chinese Society

- A Collector of Souvenirs: Photographs, Objects, and Photographs of Objects