ASTRUC Zacharie (EN)

Biographical Article

Zacharie Astruc was born in Angers on February 23, 1833, to Jean-Pierre Astruc (born in Puivert on March 10, 1806) and Marie-Victoire Franem (1817-?). His brother, Frédéric Astruc, was born in Puivert on April 19, 1845 (AN, LH/62/12).

Astruc as Journalist and Art Critic

At the age of eighteen, Zacharie Astruc moved to Lille, where he began a career in journalism, and wrote articles for L'Abeille lilloise and L'Écho du Nord. The following year, Astruc went to Paris to try his luck as a writer and was joined in 1855 by his friend, the Lille painter Carolus-Duran (Charles Auguste Émile Durant, 1837-1917); they both lived in the district of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, in the rue Férou (Carolus-Duran: 1837-1917, 2003, p. 56).

Astruc quickly turned to art criticism, and his first essay published in 1859, Les 14 stations du Salon, earned him a laudatory preface by George Sand (1804-1876) followed by a word of encouragement from Victor Hugo. (1802-1885). He subsequently published regularly in Le Pays, L'Étendard, L'Écho des beaux-arts and Le Paris illustré.

At the same time, Astruc embarked on the creation of several magazines: in 1853, while still living in Lille, he founded Le Mascarille (twelve issues from September 11 to November 28). In February 1859, he launched – a literary collection titled Le Quart d’heure, Gazette des gens demi-sérieux with Arsène Houssaye (1814-1896), Valéry Vernier (1828-1891), and Arthur Louvet thatfolded in August, after four issues. On May 1, 1863, he published Le Salon, a daily feuilleton appearing every evening during the two months of the exhibition.

La vie mondaine

As a supporter of a revival in painting, Zacharie Astruc became friends with the second generation of Realist artists: Édouard Manet (1832-1883), Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), Alphonse Legros (1837-1911), Guillaume Régamey (1837-1875), and the German Otto Scholderer (1834-1902) [Carolus-Duran: 1837-1917, 2003, p. 56]. He also defended the Impressionist painters, with whom he exhibited at Nadar (1820-1910) in 1874 (Bénézit E., 1999, p. 515).

In 1867, Astruc wrote a notice for the catalog of the Manet exhibition, and his sonnet on L'Olympia (published in the Journal des curieux in 1907) is perhaps at the origin of the eponymous work. The friendship between the painter and the critic also materialises in several canvases: Manet represents Astruc in La Musique aux Tuileries (1862, London, National Gallery, inv. 3260), in a portrait of 1866 (Bremen, Kunsthalle, inv 88-1909/1), and Fantin-Latour places the two men seated opposite each other in Un atelier aux Batignolles (1870, Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 729). Astruc was portrayed by many painters: Carolus-Duran, James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870), Félix Bracquemont (1833-1914), and Fernand Desmoulins (1853-1914).

This community of artists met regularly at the Café Molière (Rue de l'Odéon) or the Café de Bade (Boulevard des Italiens). Between 1866 and 1877, Astruc regularly frequented the Café Guerbois (avenue de Clichy) where he met Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Édouard Manet, Louis Edmond Duranty (1833-1880), Émile Zola (1840-1908), Fantin-Latour, Antonin Proust (1832-1905), Philippe Burty (1830-1890), Frédéric Bazille, Whistler, and Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). Astruc was also a regular at the receptions given by Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897) in 1870 at the Hôtel Lamoignon (Duzer V., 2014, p. 105-106).

Multiple Talents

During the first exhibition of the Impressionists in 1874 – the only one in which he participated – Astruc presented Japanese watercolours: Intérieur japonais, Poupées blanches (Drumont E., 1874, p. 2). He was present at the Official Salon in 1889 and at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900 (Bénézit E., 1999, p. 515). As a gifted draughtsman, he was praised by his contemporaries for his talents as a decorator in the design of tapestries and fans: “M. by the attractive distinction of his subjects: nasturtiums in a blue vase, geraniums and ferns, flowering pear branch, mallow flowers etc.”, Louis Enault (1824-1900) wrote about the exhibition of modern decorative art presented in 1895 at the Georges Petit gallery (Enault L., 1895, p. 26). Within Astruc's pictorial production, only a few watercolours have survived, including four in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – Deux Roses (inv. 1971.253.3),Fleurs dans un vase (inv. 1971.253.2), Fleurs blanches dans un vase (inv. 1971.253.1), Paysage avec charrette et meules de foin (1869-1870, inv. 1971.184.1) – Roses négligemment jetées sur un vase, inv. RF 41583), on in the musée des Beaux-Arts of Pau (Scène de rue à Cuenca, 1873, inv. 2006.4.1) and one in the musée d’Évreux (Intérieur parisien, 1874, inv. 8102).

As a sculptor, Astruc made his debut at the Salon des artistes français in 1871. He is known in particular for the busts of his daughter Isabelle Astruc (Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. MBA 1105), his wife Madame Astruc en espagnole (Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. MBA 1102), Manet (Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts, MBA 1103), Barbey d'Aurevilly (1876, Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 1407), François Rabelais (Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. MBA 1104) and the famous Marchand de masques (1883) in the Luxembourg Gardens (inv. RF 771, LUX 318) [Bénézit E., 1999, p. 515].

Nothing remains of Zacharie Astruc's career as a musician, apart from a few scores, a painting by Manet depicting him as a guitar player (La Leçon de musique, 1870, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) and some testimonies from friends. Advocating the decompartmentalisation of disciplines, he had been impressed by the astonishing musical accompaniment of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, which he had visited in 1857. He wanted music to be played in the exhibitions in France, but his proposal did not come to fruition (Duzer V., 2014, p. 106).

At the end of his career, on July 12, 1890, Astruc was made a chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (AN, LH/62/12).

An Early Japonisant

Zacharie Astruc is often presented as one of the precursors of Japonisme and one of the first chroniclers to note the influence of Japanese prints on the painting of his contemporaries. As early as September 1865, he wrote the first French play to incorporate Japanese elements, L'Île de la Demoiselle, which was not published but was performed privately in front of a few friends. The motifs, characters, and decorations of this "Japanese magic" (Chesneau E., 1878, p. 388) already demonstrate a solid knowledge of the archipelago (Flescher S., 1978, p. 340-347 ).

From 1864 until 1867, Astruc wrote his "Notes on Japan", nearly 70 pages including a study of the work of Hokusai (葛飾 北斎) [1760-1849] - the first in French - and descriptions of prints and albums from various collections. The critic's objective was to prepare a work divided into twelve chapters, the titles of which ("Tableau de la vie japonica", "Morals", "Industry"...) bear witness to a desire to approach Japanese culture as a whole. Also encompassing little-studied fields, such as sculpture, architecture, poetry, and music, the notes resulted primarily from two sources: Japanese travelogues and ukiyo-e prints. We know that Astruc borrowed works from the Imperial Library, and certain passages cite Isaac Titsingh (1745-1812) and Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866) (Flescher S., 1978, p. 366-373). Unfortunately, the hundred prints on which he relied are difficult to identify since Astruc did not indicate the names of the artists (except for Hokusai) and limited himself to a generic description of the scenes represented. On the other hand, he named the prints’ owners: the author himself, Philippe Burty, the watercolourist Favard, and the Comte de Rosny (Flescher S., 1978, Appendix VI). While Astruc abandoned this ambitious project in 1867, these notes probably served him in writing two subsequent articles for the magazine L'Étendard, "The Empire of the Rising Sun" and "Le Japon chez nous".

In 1867, Astruc published “The Empire of the Rising Sun” (“L’Empire du soleil levant”) in two issues, on February 27 and March 23, even before Japan's initial participation in the Universal Exhibition in Paris. The article presents a fantasised Japan, seen through the eyes of a novice who willingly concedes his shortcomings in the matter: “Indeed, through the number of documents painted, drawn or sculpted […] I can distinguish few hands. I recognise, here and there […] the presence of only five or six grand masters” (Astruc Z., March 23, 1867, n.p.). Astruc begins with the story of the rediscovery of Japanese culture by French collectors and artists in the mid-19th century, beginning with ukiyo-e prints. He emphasises the affinities between Japanese aesthetics and the research carried out by the avant-garde painters he met at the time - whom he perceived more through a certain sense of observation of living things and nature than through formal biases: “A bond tended to bring us closer: the common love of nature by which moderns will fertilise their work; inspiration demanded from the truth” (Astruc Z., February 27, 1867, n.p.).

On May 26, 1868, “Japan chez nous” (“Le Japon chez nous”) appeared, whose tone and subject are very different from the previous article. This new essay depicts three "Japanese princesses", Fleur-de-Pêcheur, Tubereuse and Acacia-Blanc, then staying in Paris. The author describes one of their homes with its many works of art, in particular two screens, one of which is a masterpiece coveted "in turn by our painters, by writers, by the most rabid collectors" (Astruc Z., May 26, 1868, n.p.). Astruc attempts a first census of Japanese art collectors of the time, which includes many painters: “Stevens, Diaz; the Gothic Tissot; the scholar M. Villot of the Louvre; the amiable watercolourist Favard; Alphonse Legros, who came from London to rejoice in his princesses; Chesneau, who exclaims and is enthusiastic, carried away by this freshness of imagination; Champfleury, whose passion for cats alone would be enough to lead to Japan, their favorite country; Solon, the prince of ceramics, the scholar, the spiritual Athenian, with unerring taste; Bracquemond erecting an earthenware temple to his Eastern masters; Fantin, surprised to find in them the Delacroix of his dreams; Burty, passionate admirer and scholar, indefatigable collector; the Goncourts, profound connoisseurs; Manet, transported by such personality; Lambron, delighted by the impulsive originality; Claude Monet, faithful follower of Hokusai” (Astruc Z., May 26, 1868, n.p.).

These artistic affinities led some of these collectors to createone of the first informal associations of Japanese art lovers alongside Astruc: the "Société du Jing-Lar", composed of Alphonse Hirsch (1843-1884), Philippe Burty, Jules Jacquemart (1837-1880), Henri Fantin-Latour, Félix Bracquemond and Marc-Louis Solon (1835-1913). The latter, then director of the Sèvres factory, organised monthly dinners at his home between 1868 and 1869 (Bouillon J.-P., 1978, p. 107-118).

The Collection

As an eclectic connoisseur, Zacharie Astruc collected ancient and modern painting, sculpture, furniture and Japanese art.

The Collection of Paintings

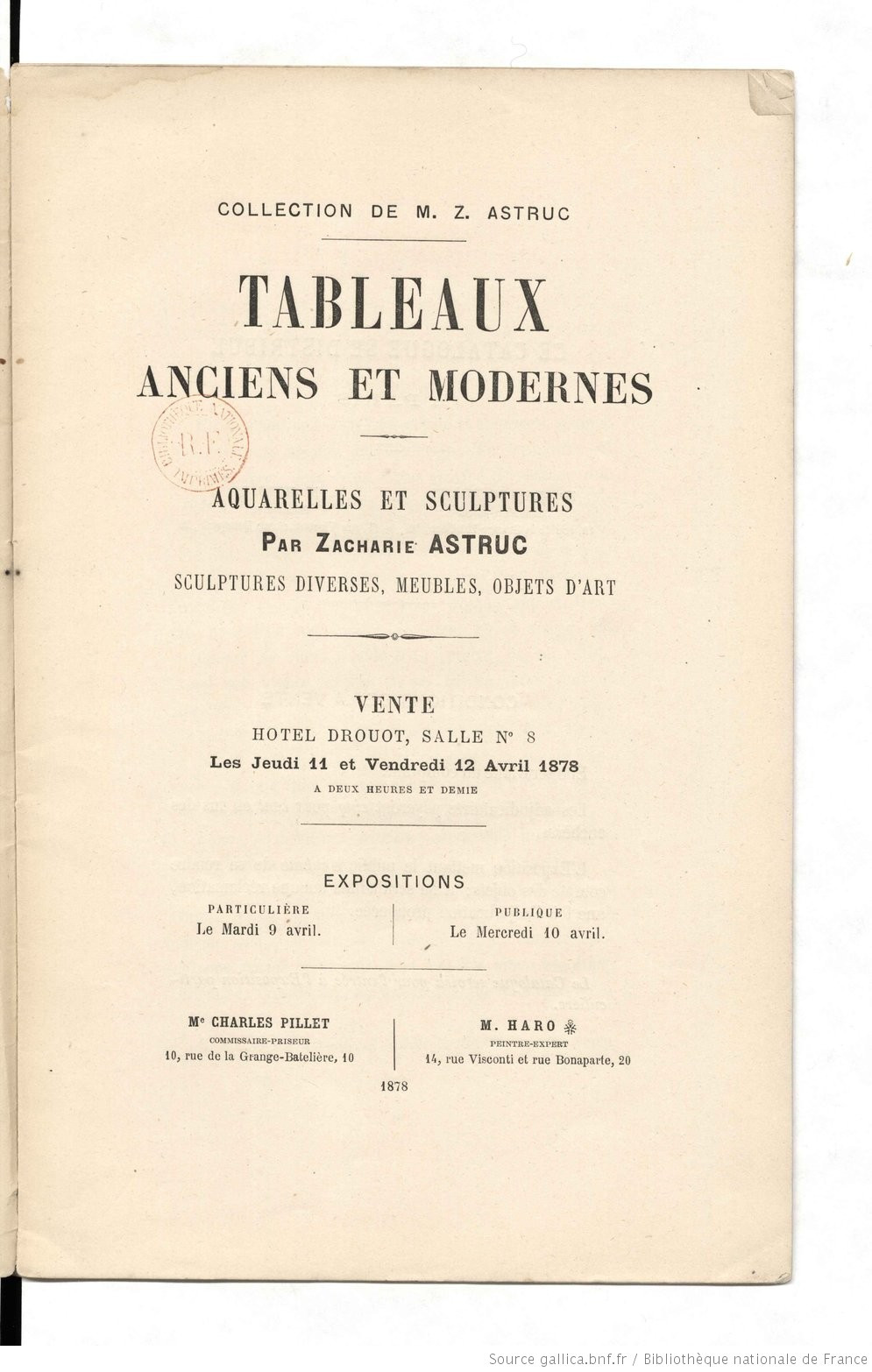

In the auction catalog Tableaux anciens et modernes : aquarelles et sculptures par Zacharie Astruc : sculptures diverses, meubles, objets d'art of April 11 and 12, 1878, Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890) explains the manner of formation of Astruc’s collection of paintings, which probably began in the late 1850s: "Mr. Zacharie Astruc exhibits at public auction a large part of the paintings, both ancient and modern, that he has managed to collect over the past twenty years. This collection was formed not only in Paris, but also during his frequent trips to England and Flanders, and during his long stays in Spain […]” (Tableaux anciens et modernes, 1878, p. 57). Among the 98 paintings listed in the catalogue, the French school hangs alongside the schools of the Spanish, English, Flemish, and Dutch.

The French school is divided between ancient paintings and modern paintings. On the one hand, there are 18th century paintings with Nature morte. The school includes Le Gigot by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755), a Portrait of Jean Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), and several works by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1731-1799)– La Madeleine en méditation, Le Prédicateur villageois, a Portrait de l’artiste, Le Berger musicien. Soir d’automne, Cavaliers dans une forêt, or La Toilette de Vénus – which “are said to come from the Marcille collection, which I have no trouble believing. Thoré, moreover, praised it when it appeared at the exhibition of the masters of the French school in 1865, on the Boulevard des Italiens” (Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, 1878, p. 9). On the other hand, the 19th century, dominated by the Barbizon school with La Résurrection (sketch in Reims, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. 928.13.13) by Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), Le Tronc d’arbre by Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), a Portique romain by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875), and three works by Constant Troyon (1810-1865), Le Chasseur de ferret, La Chaumière, and Intérieur de forêt. Also worthy of note are studies by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1758-1823) - La Justice poursuivant le crime (1804-1806) and Le Christ en croix (the two completed paintings of which are at the Musée du Louvre in Paris) - and Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) – Écurie dans l’église de Saint-Nicolas, Le Cellier normand and Cheval au râtelier. Other sources (Wildenstein D., 1974, no 3 and no 84) mention the presence in the Astruc collection of works by Claude Monet (1840-1926): a view of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois (purchased by Durand-Ruel in 1872) and a Pochade, Bouvières (bought from Monet in Paris in 1877).

Regarding the Spanish School, the sales catalogue mentions four canvases by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) - Enfants jouant au moine, Enfants jouant au soldat, Petite-fille de l’auteur and Nature morte - and four works by El Greco (1541-1614) – Le Rier, La Vierge et l’Enfant-Jésus, Adoration des bergers and Saint François d’Assise recevant les stigmates. Of this last artist, we know that Astruc also owned a Saint Dominique (c. 1605), which he later sold to Degas, in November 1896, for 3,000 francs (now preserved in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 23.272) (Degas, 1988, p. 492). Finally, the Drouot catalogue mentions a sketch by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), the Procession de la Vierge d’Atocha.

The Flemish and Dutch school is notably represented by two altarpieces. The first, dating from the 15th century, is attributed to Hans Memling (1430-1494). This monumental work is composed of fifteen panels representing Le Triomphe de la rose rouge, namely the reconciliation of the houses of Lancaster and York with the assistance of the Virgin. The second, a triptych (now kept in Brussels, musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, inv. 2786), is the work of Frans Floris (1517-1570): the central panel is illustrated by the Adoration des mages, framed by the Evangelists on the side panels. Other pieces include two works by David Teniers (1610-1690) - LaTentation de saint Antoine and Le Singe à l’orange –, LaNuit de Noël by Jan Steen (1626-1679), Le Jeune Musicien by Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667), a view of Dordrecht by Albert Cuyp (1620-1691) and a Vue prise en Hollande, aux environs de Zaardam by Jan Van Goyen (1596-1656) dated 1634.

Finally, the English school is also present with La Coupe de Benjamin by Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), Le Parc by Richard Parkes Bonington (1802-1826) and three canvases by John Constable (1776-1837): Lisière de forêt, Le Moulin and Campagne anglaise.

Apart from the paintings, the catalogue lists nine sculptures (including two terracottas by Alonzo Cano, 1601-1667, and a small marble bas-relief by Germain Pilon, 1528-1590), twelve pieces of furniture (from the Louis XVIII and Louis XIV, as well as Hispano-Moorish furniture, two Arab cabinets and a Chinese screen), two tapestries and a sixteenth-century Indian bedspread, three Spanish earthenware vases, two sixteenth-century Arabic lamps, and a Persian ewer.

An Early Collector of Japanese Art

Like the Goncourt brothers or Ernest Chesneau, Astruc regularly represented himself as a pioneer in the discovery of Japanese art, "the first in Paris (will this glory at least be reserved for me?) [who] wanted to write about the grandeur and exquisiteness of their production” (Astruc Z., May 26, 1868, n. p.).

In the absence of a diary or letters, however, it is difficult to determine the date of his discovery of Japanese art, as well as that of his first acquisition. We know that in 1863, Astruc had the opportunity to admire prints from the collection of Baudelaire (1821-1867) and that he was so struck by them that he compared them to the vibrant colours of the paintings of Delacroix (1798- 1863) [Astruc Z., May 2-3, 1863, p. 2]. By the end of 1866, he already possessed many Japanese prints, picture books and works of art – including the Manga and other works by Hokusai – which he used to write the preparatory notes for his articles in L’Étendard. Among the many illustrated albums acquired by Astruc, four have been kept by his descendants: first his only daughter, Isabelle Doria (? -1952), who then entrusted them to Christian Reiss in 1944; they remained in his posession (Flescher S., 1978, p. 386). They consist of illustrated books by Yanagawa Shigenobu II (柳川重信, active circa 1824-1860), Utagawa Toyokuni (歌川豊国, 1769-1825), Katsukawa Shuntei (勝川春亭, 1770-1820), and Ryokutai Senryu (1800s ?). Shigenobu II's album, the Ehon Fujibakama (絵本ふちはかま), is the first of a two-volume series published in 1823, collections of moral tales about virtuous women. In the portrait of Astruc by Manet (1866, Bremen, Kunsthalle), it seems that the work placed on the work table, with the dark green cover and the title in ideograms, is the Ehon Fujibakama. Toyokuni's album, Osugi Otama Futami No Adauchi, was published in 1807. Shuntei's, Kuraiyama Homare No Yokuzuna in 1812, brought together several fantastic tales. Finally, the fourth and last book, illustrated by Senryu and named Seichu Gimin Ryakuden, appeared in 1862. These four albums all date from the 19th century and show a certain predilection for the representation of human figures (images of plants and animals are absent). For Astruc as for other art lovers of the 1860s, it was difficult to obtain prints from the 17th and 18th centuries.

At age forty-three, for unknown reasons, Astruc decided to part with most of his collections; paintings, prints, and works of art were sold on April 11 and 12, 1878 at the Hôtel Drouot. However, no Japanese objects appear there, so that apart from the four albums mentioned above, the location of the rest of the collection remains unknown.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne