ZAFIROPULO Polybe (EN)

Biographical Article

The Zafiropulo family was part of the Greek diaspora, as were the Zarifi, with whom they shared a common ancestor, Demetrius Zafiropulo (1790-1864), who had started a flourishing wool and wheat trading business. At the insistence of his father, Georges went abroad to study, along with his brothers Étienne and Constantin. He moved to Marseilles and eventually founded a trading house (Lafon-Borelli M., 1995, p. 45). In 1864, he married Christine Lascaridis, from a Greek family already established in the city. Their son Polybe was born four years later in Constantinople. In 1875, the family returned to Marseilles (Lafon-Borelli M., 2017, p. 82). Business prospered, but, suffering from blindness, Georges Zafiropulo was forced to leave the management of the company to his brothers. He later joined forces with his brother-in-law, Georges Zarifi (1806-1884) in 1852 to found the company "Z & Z". Périclès Zarifi (1844-1927), father of Nicolas Zarifi (1885-1941), a collector versed in Asian arts, succeeded his father (Lafon-Borelli M., 1995, p. 45).

Like other Greek families settled in Marseille, the Zafiropulo were involved in the local economy and participated in its development. Polybe staked his independence from family affairs, while maintaining strong ties with his native land.

A Representative of the Hellenic Community, Conscientious of his Origins

As a representative of this community, Polybe Zafiropulo defended its interests and remained concerned about the political situation in his country of origin while indebted to his second homeland. The national schism looming in Greece was felt as a personal heartbreak. As part of the Congress of Greek Colonies, held on May 31, 1916, he was indignant at the laxity of the Greek government, which was neutral until 1917. Opposing his Prime Minister Elefthérios Venizélos (1864-1936), King Constantine I (1868-1923; r. 1913-1917 and 1920-1922), refusing any intervention by Allied troops, allowed the Bulgarians to enter Greek territory in Macedonia. In a letter addressed to the prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône on June 9, 1916, published the following day in the press, the community renewed its attachment to France (Le Petit Marseillais, June 10, 1916).

Polybe Zafiropulo, concerned by the conflict in the Balkans, also defended the economic interests of the diaspora. He was thus on the board of directors of the Greek Chamber of Commerce, located at 3, rue Estelle, of which he became president in 1927.

Efforts for the Adopted Country

Polybe Zafiropulo also worked for his adopted homeland. He upheld an ethic of giving, which inspired the great industrial families of Marseilles, and he participated in several charitable projects, especially after the First World War (1914-1918).

He created a subscription for the families of the victims of the shipwreck of General Chanzy, stranded on the coasts of Menorca, in the Balearic archipelago, while the ship was making the Marseille-Algiers crossing in February 1910. During the war, he participated in the Rescue Committee for Girls' Schools Belle-de-Mai, in 1914, and was involved in Christmas for orphans in 1917. He donated to the Marseille Daily Press Assistance Committee (Comité d’assistance de la presse quotidienne de Marseille), a charity for war victims, and to the Red Cross in 1918. His wife, Sophie Economo (1869-1940), whom he married in 1896, actively supported him in this charitable work (Borelli J., 1985).

A Worldly and Leisurely Life

Polybe Zafiropulo showed himself to be "naturally curious and enterprising" (Borelli J., 1985). Because he appreciated physical exercise, he joined the la Société sportive de Marseille. He was passionate about motor sports and took an interest in the competition cars of the manufacturer Turcat-Méry (Borelli J., 1985), whose company went bankrupt in 1929.

Sailing was another hobby. He enjoyed drawing the plans of the yachts that he had built (Borelli J., 1985). Following the example of his father, he became a member of the Société Nautique de Marseille, an organiser of international regattas. He was thus seen competing aboard his sailboat called Léda in February 1896 in the port of Toulon and in Cannes, for the national Rothschild cup (Dufréne X., 1897, p. 2), then in Marseilles in 1899 with the same boat (Journal des sports, February 13, 1899, p. 3). Appointed for the year 1896 as advisor-commissioner within the company (Le Petit Marseillais, February 25, 1896, p. 2), he participated in the jury of the competition the following year and joined the organisational committee of the tests in 1898 and 1930 (Le Radical de Vaucluse, February 7, 1930, p. 5).

His means allowed him to rent the spaces necessary for the satisfaction of his leisure activities. For fishing, he took over the island of Riou (Borelli J., 1985); for hunting, he was given use of the Relais marsh, near the mouth of the Rhône (Borelli J., 1985).

The Mediterranean Electricity Company

As a graduate of the Lausanne engineering school, of an independent nature, Polybe Zafiropulo broke away from the family company Zafiropulo et Zarifi. He set up a first company with his brother Eugène and Félix Tennevin, an arts and manufacturing engineer. On November 9, 1893, the company, in collective name, under the name "Société d'Électricité de la Méditerranée", was registered by private deed with the commercial court of Marseille. The company, placed under the name "G. Zafiropulo fils & Tennevin", with a registered office located at 57, rue de Rome, worked in the installation of electric lighting for factories, central stations, cafes, theatres, casinos, and other public or private premises, in particular within the framework of receptions.

Thriving Refrigeration Business

In 1895, Étienne, Alexandre, Eugène, and Polybe teamed up with Alexandre Arnal, a dyer by trade, to set up a refrigeration company. The registered office was temporarily located at 57, rue de Rome. The duration of the company, with a share capital of 150,000 francs, was estimated at around ten years. Arnal seems to have withdrawn from the project, giving the Zafiropulo the freedom to reclaim the company in 1897 (Borelli J., 1985), now known as "Zafiropulo Frères". Alexandre, Étienne and Polybe thus formed the Société frigorifique et de glace pure de Marseille, provider of the main shipping companies, as specified in the announcement published in the Marseille Indicator of 1898.

Jacques Borelli explains the operation of the company, which "rented meadows in the region of Serre and Aspres-sur-Bech and flooded them in the fall so that they would be covered with ice in winter" (Borelli J., 1985). The ice was brought back by truck or train to Marseille itself, stored in cubes in cold storage warehouses, pending sales during the summer period (Borelli J., 1985). However, the company had to deal with significant losses of goods, which led it to consider another manufacturing process, by compression and expansion of ammoniacal gas (Borelli J., 1985). The plant on boulevard de Plombières was built for this purpose, as was that on boulevard Gueydon, located in Saint-Mayants, a district located in the south of the port area of Marseille (Borelli J., 1985).

In 1900, Zafiropulo Frères joined the Société anonyme des glacières de Paris. The company supplied natural ice from Lake Sylans and the Alps, while the Zafiropulo supplied pure, so-called "hygienic" ice, made with sterilised water heated to 150°. They thus joined the management installed at 6, boulevard Saint-Charles. The factory park expanded, taking into account the factory of La Glacière marseillaise, at 20A, rue d'Alger. The business was prosperous and beat the competition, according to Jacques Borelli (1985). He was thus nicknamed in the middle the "father of ice" (Borelli J., 1985).

As he set several milestones in the cold chain, he was on the board of directors of the then-recently created Société anonyme de la Compagnie des viands in 1929.

The Zafiropulo factory was finally destroyed during the war, in 1943. Faced with this loss, the company sold its shares to Glacières de Paris (Borelli J., 1985).

Real Estate and Bankruptcy

After the war, Polybe Zafiropulo entered the real estate business. Because he sensed the financial goldmine of the coastline, he acquired several plots of land in Lecques-sur-Mer and had them subdivided. This was the beginning of the Société immobilière du golfe des Lecques (the Real Estate Company of the Gulf of Lecques), which he founded with Georges Zafiropulo, with a capital of 500,000 francs. But this society only lasted a while. The company’s administrator, the notary of Le Cheylard, precipitated the bankruptcy of the company and led it to compulsory liquidation (Borelli J., 1985). Polybe Zafiropulo thus felt compelled to part with Château Cordion, his country home, which was located nearby. He emptied it of its furniture and collections during a public sale in 1936. He managed to limit the losses "by reimbursing the creditors in his capacity as President" (Borelli J., 1985). This affair, his widowhood, and the war affected him deeply, especially since he had lost part of his fortune (Interviews, 2022). Suffering from neurasthenia, he was hospitalised. His son Jean took over the business and left it to Tibaut, a former accountant and secretary to his father after the war (Borelli J., 1985).

Polybe was treated at the clinic in the Vauban district. The news of his daughter Nora's marriage in 1947 and the birth of his grandson restored his taste for life (Borelli J., 1985). In this respect, Jacques Borelli evokes a "miraculous" cure (1985). He then set up a small studio on the boulevard Périer, in 1949, where he lived until the end of his life (Borelli J., 1985).

The Collection

It is difficult to grasp the entirety of the collection, which underwent several movements. The entrepreneur, who had to part with pieces of his collectionson several occasions, followed many reversals of fortune. Indeed, after his death a last movement led to the dispersion of the whole. However, the collector showed consistency in his artistic orientation and demonstrated a marked inclination for Provençal furniture and local earthenware. The photographs of his interior at 13, rue Édouard-Delanglade and the publications, reporting on the exhibitions in which he participated, give glimpses of the collection, which allow us to understand his tastes in decoration.

The entourage of Polybe Zafiropulo included many examples of collectors from whom he could draw inspiration to create his own, which was marked by a taste for Provençal art, embellished with touches of exoticism.

The Shared Taste for Provençal Art

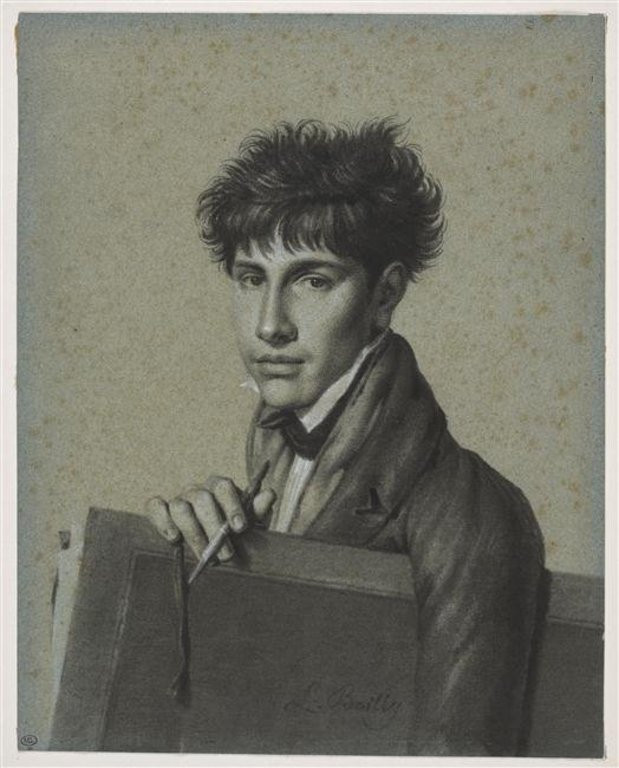

His appetite for regional art seems to have remained strong throughout his journey of collection. In an exhibition of Provençal art in the Grand-Palais, inaugurated on May 7, 1906, he exhibited a self-portrait of the Marseilles painter Gustave Ricard (1823-1873) and another of his works, the portrait of a Marseilles banker, Félix Abram, portrayed at the age of thirty. The same year, he lent a batch of Marseille earthenware to the Colonial Exhibition in Marseille. He completed his collection in 1912 and bought " a large dish of Saint-Jean du Désert (3,900 francs), two bouquetiers by Le Roy (4,630 francs) and a powder box from Moustiers (450 francs) in quick succession " (De Ricci, 1912, p. 6). His Renaissance period cupboard illustrates an article on Provençal furniture in the Gazette des beaux-arts in January 1913. Gustave Arnaud d'Agnel (1871-19?) cites some pieces from his collection to illustrate his work on Provençal furniture (1929) and on Marseille earthenware (1911). As Vice-president of the section devoted to Provençal furniture at the Colonial Exhibition of 1922, he showed other pieces, which he accompanied with a set of earthenware. In 1932, he also participated in the Exposition des Arts décoratifs de Paris and took advantage of his stay in the capital to visit the sales rooms of the Hôtel Drouot. In 1935, he participated in the collective presidency of the Exposition d’art antique et moderne, honouring religious art.

An Eclectic Collection

The sale of the collection of Marseilles soap maker Arnavon, faience from Marseille and Moustiers and foreign porcelain, held in 1902, marked the beginnings of his taste for collecting (Lafon-Borelli M., 1995, p. 46). The photographs of the hôtel particulier on rue Édouard-Delanglade present a heterogeneous ensemble (Lafon-Borelli M., 2017). The walls are hung with Aubusson and Flanders tapestries, the interiors lined with Regency and Haute Epoque furniture. Earthenware from Apt, Moustiers, and Marseille are displayed in the window. It is also possible to discern a note of exoticism in a fruit bowl from the manufactory of Marseilles with so-called "Chinese" decoration. Arnaud d'Agnel also cites Persian-style ornamentation with a ewer from the manufactory of Saint-Jean-du-Désert, in its second period (1911, p. 222-223). In this opulent interior, a few porcelain from the Far East also creep in, even if it is difficult to determine their provenance, given the vagueness of these archival photographs (Lafon-Borelli M., 2017).

The sale of Château Cordion in 1936 completed the vision of this collection. Here we find a taste for Provençal art and this interest in Louis XV and Louis XVI style furniture. In addition to the paintings of the 18th century French school and the presence of local artists, such as the Marseilles painter Adolphe Monticelli (1824-1886) [Arnaud d'Agnel G., 1926], earthenware from Marseilles and Moustiers feature prominently and join other productions from the factories of Delft, Jacob, and Petit. The catalog also mentions French and foreign porcelain, but does not give a more precise description of the objects placed under lot no. 16. There are also many omissions and unlisted objects, as indicated at the end of the inventory.

A Discreet Taste for Asia

Under lot number 18, porcelain plates from China and the Compagnie des Indes were presented. Old Oriental rugs and various hangings were also on sale, including a beautiful Persian rug with geometric designs on a blue background, with a polychrome border (lot 116). The layout and decoration of the rooms visible in the illustrative photographs of the catalogue are still marked by a significant taste for Provençal art. But Asia does constitute an element of decoration, although discreet.

The collection also includes Chinese porcelain, testimonies of artistic exchanges between China and the Persian Empire, such as a kinrande ewer made for the oriental market. He undoubtedly developed this taste for oriental and Far Eastern ceramic because of his origins, as a descendant of Phanariot families (Interviews, 2022). There was also a pair of celadon vases, and a bronze statuette representing an immortal.

It is also possible to pick up a note of exoticism in certain Provençal productions, such as the fruit bowl from the Marseilles factory with so-called "Chinese" decoration. Arnaud d'Agnel also evokes the Persian-style ornaments of a ewer from the Saint-Jean-du-Désert factory, in his second period (1911, p. 222-223).

Certain religious objects relating to Orthodox worship are preciously preserved and refer to the origins of the collector.

In conclusion, Polybe Zafiropulo was a "man of culture, a great aficionado, a collector, but also an enlightened connoisseur of art" (1995, p. 47). Following multiple reversals of fortune, he was forced to part with his collection, which he dispersed at auction or through amicable transactions in his circle of acquaintances. Some pieces have entered the collections of the city of Marseille and are exhibited at the Château Borély. Yet, seconding Marina Lafon-Borelli, the absence of an inventory of the collection is regrettable (1995, p. 47).

![[Grand salon de l’hôtel particulier de Polybe Zafiropulo]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/0/csm_Zafiropulo2_3823fd2036.jpg)

[Grand salon de l’hôtel particulier de Polybe Zafiropulo]

[s.d.]

Photographie

Collection privée

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne