CANTINI Jules (EN)

Biographical Article

Jules Cantini was the youngest child in a large family, originally from Pisa. He was the son of Gaëtan Cantini (? -1831), an entrepreneur and “modest worker of marble” (Barré H., 1913, p. 109). Having come to Marseilles at the beginning of the 19th century, he founded his studio in 1808 (Barré H., 1913, p. 109) and developed his business in 1823, joining the project to redevelop the Porte d'Aix, by obtaining the commission for the demolition of the aqueduct (Richard É., 1999, p. 103). On the 13 Frimaire Year XIV [December 4, 1805], he married Marie-Thérèse Magdelaine Farci, who ran a small poultry and food business in the 1830s (Richard É., 1999, p. 103).

While Cantini professed to belong to the Italian community, he considered Marseille his adopted homeland. He was naturalised on February 15, 1888 (AN, BB/34/394 / 13231 X 87). The marble worker carried out numerous actions in the public domain and became known for his ornamental work in the Sainte-Marie-Majeure cathedral, known as "La Major". In this sense, he came to be "in the forefront of Marseille celebrities", to use the expression of historian Éliane Richard (1999, p. 105).

Jules Cantini: Marbler-Sculptor

Jules Cantini entered the free school of drawing in Marseille (the future école des Beaux-Arts), with his older brother Pierre, who founded a decorative sculpture workshop in rue des Beaux-Arts. In 1851, the apprentice mourned the untimely death of his younger brother. Jules then took over the family business and made it "a real industrial company" (Raveux O., 2007, p. 55). In the Indicateur marseillais of 1852, he was designated as “marble worker-trader”. At the time, he held a patent for a mechanical sawmill. The following year, the guide reported the foundation of a marble sawmill in Saint-Giniez, which was definitively fixed in 1859 in the chemin du Rouet.

In 1856, Jules Cantini married Rose Louise Augustine Lemasle (1826-1922), daughter of a saddle maker and wagon builder. Upon his marriage, he left the family home on rue Longue-des-Capucins to settle at 8, cours Lieutaud, in the same neighborhood. The Prado workshops were established in 1857. He then set up his home nearby. From 1855 to 1863, the rising industrialist also had a subsidiary in Paris, at 248, quai Jemmapes, on the Saint-Martin canal, then in 1860, at 39 bis, rue Sedaine, in the 11th arrondissement.

At the height of modernity and technical innovation, the marble mill ran on steam power. The entrepreneur also acquired quarries in Italy and North Africa. Conscientious of the quality of the product, he placed special emphasis on the notion of colours and the play of polychromy in his own creations, as noted by his contemporaries (Macé de Lépinay J., 1902, p. 337 and Delanglade Ch., 1921, p. 281); as a sculptor, he made use of "white marble from Carrara, yellow marble from Numidia and red marble from Provence" (Raveux O., 2007, p. 55). Jules Cantini was also notably the owner and operator of the Vitrolles quarry (Indicateur marseillais, 1914, p. 1540).

According to him, his workshop, "one of the first in France from the viewpoint of artistic marble", had 150 workers and artist-sculptors (AN, LH/419/98). For ten years, he chaired the Chambre syndicale des entrepreneurs de bâtiments of Marseilles. The Syndicat des Industries du bâtiment des Bouches-du-Rhône granted him an honorary presidency.

Cantini was at the origin of many achievements in the Marseilles capital, and said that he had "executed all the marble works of the monuments of Marseilles without exception" (AN, LH/419/98). The entrepreneur also worked in Paris, in particular for the construction of the private mansion of Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), avenue d'Iéna, which he finished in 1886. He was also active abroad, in Constantinople, Greece, Africa, and India, where he responded to individual as well as public orders. In 1906, the industrialist withdrew from the company and entrusted its management to his nephew and collaborator Marius Cantini (1850-?) (Richard É., 1999, p. 105).

A "Servant of Eternal Art" (Rémy Roux)

His meeting with the architect Léon Vaudoyer (1803-1872) was decisive in the launch of his artistic career. He completed the cathedral, the first stone of which was laid on September 26, 1852, by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (1808-1873), the President of the Second Republic, who entrusted him with the task of ornament. Jules Cantini saw to the elevation of the columns, friezes, and pilasters, as well as the statuary, in Byzantine style. This work permitted him to establish his reputation as a sculptor-marbler. He would never stop insisting on his status as an artist.

The city of Marseilles had many of his creations, which he presented at various exhibitions. The sculptor and medalist Charles Delanglade (1870-1952), who succeeded him at the Académie de Marseille, underlined the importance of "the presentation in a work" and the need for the artist to penetrate it (1921, p.281). "He understands that a mind cannot imagine forms and figures without their attributes and mood" (1921, p. 281). Delanglade also conceded that he had a "taste for sumptuous form and coating" and a certain "arithmetic precision" in his artistic choices (1921, p. 278). In 1900, Jules Cantini fashioned "Nature Unveiling herself before Science” out of onyx discovered by Marius in in the Aïn-Smara quarry in Algeria, near Constantine, according to the instructions of the Bishop of Marseilles (1878-1900), Louis Robert (1819-1900). It was an interpretation of the work of Louis-Ernest Barrias (1841-1905), teacher of Charles Delanglade, who lauded him for this work. The state acquired one of his works at the Universal Exhibition of 1900. On the other hand, the "Bon Accueil", composed for the Colonial Exhibition of 1906, did not meet the critic’s expectations. In a public speech in the large amphitheater of the faculty of sciences on June 15, 1919, his tone was acerbic, sometimes ironic, sometimes ambiguous, oscillating between the standard praise of an honorable predecessor and the wish to show another facet of his character, whose egocentrism and selfishness surface at certain times in the text. Charles Delanglade in effect questions the artist, suggesting that he should have associated himself with a master sculptor and qualifying him as a "dilettante artist" (1921, p. 289).

If his work was appreciated in varying degrees, according to Charles Delanglade (1921), it was at any rate praised by his peers and rewarded in practice with numerous decorations. He received the gold medal at the Marseille Exhibition in 1861 and at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1878. Two honorary diplomas were awarded to him in Montpellier in 1885 and Marseille in 1886. He won the Grand Prix of the Universal Exhibition of 1889, for a white marble fireplace in the Louis XIV style, which he composed and executed for a Parisian hotel. He was also awarded the highest distinction at the Universal Exhibition in Liège in 1908.

He was also invested in the teaching of fine arts. In 1870, he founded a sculpture and painting section and set up a scholarship system to help young talents. He was received in March 1902 at the Academy of Sciences, Letters and Fine Arts of Marseille, inducted by the sculptor André Allar (1845-1926), to the chair of the painter Dominique-Antoine Magaud (1817-1899). He was appointed vice-president of the Fine Arts Commission and president of the Friends of the Musée du Vieux-Marseille. As a member of the inspection and surveillance committee of the Longchamps museum, he obtained the vice-presidency of the section devoted to Provençal arts, within the Colonial Exhibition of Marseille in 1906, in which he participated out of competition.

While Charles Delanglade proved to be critical of the talent of the sculptor-marbler, the municipality of Marseille, in the person of its assistant delegate for the fine arts Rémy Roux (1865-1957), praised a patron and "servant of Eternal Art". At the opening of his eponymous museum in 1936, Jules Cantini also appeared as a "patron who adorns Art and the City" (quoted in Comœdia, 1936, p. 3).

"Patron Who Adorns Art and the City"

His philanthropy was demonstrated by various acts. On November 12, 1911, a fountain bearing his name was inaugurated on Place Castellane. Jules Cantini is the designer, André Allar, the sculptor. Le Petit Marseillais describes a work of "social generosity" (Thomas E., 1911, p. 3). The large building, representing the three rivers that irrigate Provence - the Durance, the Rhône and the Gardon - and the Mediterranean Sea, required some adjustments. The obelisk, erected in 1811 by the architect François Michaud (1810-1890), director of public works for the city, and interpreted by Panchard, wound up moving to the Mazargues roundabout.

In 1913, Jules Cantini also donated a reproduction of Michelangelo's David to the City of Marseilles, which would later go to the Palais Longchamp. Since 1949, the statue has marked the intersection of avenues du Prado and avenues de Pierre-Mendès-France. Among other things, he designed decorative elements for the church of Montolivet and for the altar of the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde. He was also the creator of the Puget monument, rue de Rome, which replaced the original fountain that was considered to be in poor condition (Négis A., 1912).

Jules Cantini thus established a strong presence in the city of Marseille. His achievements constitute "indisputable landscape markers" (Raveux O., 2007, p. 56); some of his works led to a reconfiguration of urban space.

Philanthropist

Through his involvement in the cultural life of his country and his city of Marseilles, the patron’s generosity was of another order and encompassed other aspects of the life of the city. For those who knew him, this was another step in his journey. Towards the end of his life, he began to come to the aid of the most needy. Jules Cantini founded the Society for the Poor (la Société pour les pauvres), of which he became president. He founded the Workers' Mutual Aid Society (la Société ouvrière de secours mutuel). On the occasion of his diamond wedding anniversary, on June 20, 1915, Cantini and his wife offered 225 savings bank accounts, worth 100,000 francs, for families in Marseilles who were victims of the war (Le Temps, 1915, p. 4).

In 1917, the donation of the chateau on the hill of Marseilles-Veyre and its 19 hectares of meadows and pine forests to the city's hospices was recorded, on the condition that if nothing was done for its use, an equivalent donation would be offered to the city of Pisa. The Italian Mutual Aid Society of Marseilles (La Société italienne de secours mutuel de Marseille) also received an amount of 20,000 francs. The industrialist in Marseilles had not forgotten his origins.

For his social investment, Cantini was ordained a Knight of Saints-Maurice-et-Lazare, an ancient honorary order which rewards the help given to the most needy and

to the sick, according to the precepts of a fervent Christianity. "The heart opens and strives to create sympathy", as Charles Delanglade cynically notes, who sees in the journey of the marbler-sculptor a strategy of social conquest (1921, p. 284). His successor at the Academy of Fine Arts underscored the self-interested character of the prosperous industrialist, millionaire and holder of significant real estate capital, concerned with social recognition, who would be intentionally lavish in his philanthropic actions. Delanglade thus noted “two stages in his life. The first was to concentrate his means of action and to definitively establish his fame as well as his fortune. The second part was to radiate the accumulated products of his hardworking life around him.” (1921, p. 282). Rémy Roux preferred to highlight the figure of the patron and prodigal philanthropist towards his hometown and emphasised the empathy of an "old man who comes to the aid of old men like him" (quoted in Comœdia, 1936, p. 3).

These works earned him the rank of Knight (chevalier) of the Légion d’honneur (AN, LH / 419/98), by decree of the Ministry of Trade and Industry (ministère du Commerce et de l’Industrie) on January 4, 1887, which was then sponsored by Joseph Letz (1837-1890), chief architect of the Bouches-du-Rhône department since 1868. Jules Cantini was promoted to Officer of the Légion d’honneur by decree of the Colonial Ministry on July 17, 1908, and was then received by André Allar, member of the Académie des beaux-arts. The marbler-sculptor thus received social, municipal, and national recognition. The legacy of the residence at 19, rue Grignan, which the city was responsible for turning into a museum, definitively marked his concern for social and artistic work.

The Collection

Jules Cantini’s will of December 30, 1916 (AD 13 / 362 E 640)bequeathed the Hôtel Montgrand and all of its collections to the city of Marseille. This 17th century residence, in Louis XIV style, built in 1694 by Nicolas Charpentier and inhabited successively by the Compagnie du Cap Nègre, the Montgrand family, the Count of Grignan, the governor of Provence, and by the Cercle des Phocéens, was a privileged setting for the collections until they were spread out between his villa on avenue du Prado and in his country house, which was located on the outskirts of Marseille.

A Decorative arts Museum for the City of Marseille

In 1888, Jules Cantini took possession of this property, which he rented to the Cercle des Phocéens. A progressive association of local notables made it its headquarters and proved to be at the origin of notable transformations, which distorted the interior of the building. The tacit renewal of the lease and fruitless talks delayed the opening of the museum.Furthermore, many repairs turned out to be necessary in order to accommodate the collections. Jean-Amédée Gibert (1869-1945), former curator of the museums of Marseille, designed the plans. Seventeen years would pass before the establishment finally opened its doors to the public, on April 16, 1936.

As specified in his will, the museum would house "paintings, engravings, drawings, tapestries, sculptures, antique furniture and seats, bookcases, showcases of ivories, jades, bronzes, marbles, and all works of art and curiosity found at his home" (AD 13, 4 O 58 59).

For Rémy Roux, the Musée Cantini represents "the Petit Palais of Marseille, the museum of decorative art, of social art" (E. E., 1936, p. 3). Such was the image of the collection peddled by representatives in Marseilles and the populist press. Paul Quilici spoke of a "directive" socialism, which gave the proletariat access "to the enjoyments of an intellectual order reserved, unfortunately until now, for the privileged, fortuned few" (1937, p. 6).

When it opened, donations poured in. But even before the creation of the museum, Jules Cantini had already made numerous donations to the city of Marseille: one on February 1, 1896, and another on January 31, 1917, accepted on February 12, 1919 by the prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône, Lucien Holy (1867-1938). Engravings and lithographs were also entrusted to the Musée du Vieux-Marseille in May 1912. An original drawing by Daumier and two paintings by Jean-Baptiste Olive (1848-1936) completed this donation. Sixteen earthenware pieces from Marseille would further enrich the collections of the same museum.

An Open Collection

At its inauguration in 1936, the collection of the Musée Cantini comprised more than 1,500 pieces, a number that owed itself to donations from close friends, such as Philippe Jourde (1816-1905) and Nicolas Zarifi (1886-1941). The local press gave a snapshot of this collection (Martin-Duby, 1936), which could even be said to have continued posthumously: indeed, in the specifications of the commission attached to the museum, the collector required the regular purchase of works by contemporary artists who exhibited at the Paris Salon, with the excess income from the museum, at an annual value of 50,000 francs (AD 13, 4 O 58 59).

An Eclectic Collection

It is worth noting the eclectic character of the collection, oriented more towards the Italian and French Renaissance and the 18th century. Tapestries from Beauvais depict the fables of La Fontaine. There are panels signed by François Boucher (1703-1770), Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), Adriaen Van Ostade (1610-1685), as well as paintings by Adolphe Monticelli (1824-1886), the Marseilles painter known for his textured canvases. A cabinet brings together the drawings and engravings of regional artists. A portrait of Molière interpreted by Sébastien Bourdon (1616-1671) stands alongside a child's head sculpted in wood by Pierre Puget (1620-1694). A bronze by Antoine Louis Barye (1795-1875), representing the Duchess of Angoulême, was held in great esteem by commentators.

The Collection of "Chinese" objects

The "showcase of Chinese objects and vases", which the visitor reached after climbing the stairs, ultimately went unnoticed by contemporary critics (Martin-Duby, 1936). The label was also misleading, as it contained objects of various natures and origins. Objects of curiosity and visual delight had no part in the decoration of the private mansion. The inventory includes around a hundred Asian art objects. Vases and Satsuma incense burners dominate the ensemble. A Gyoran Kannon is particularly highlighted. Jules Cantini's collection demonstrates a certain taste for Satsuma stoneware products, which correspond to a general enthusiasm on the part of Westerners since 1878, with the Universal Exhibition in Paris. This enthusiasm can also be explained by the marmoreal tint of the glaze, an evocation of the marble that Jules Cantini handled on a daily basis. The name of the Kinkozan workshop, at the head of the export trade (Klein, A., 1984), comes up twice. One of these works consists of floral motifs, declined in soft colours, highlighted by black lines and sprinkled with gold (nishiki-de) on a milky background. The other piece shows a typical street scene, described in medallions on a black background, which was characteristic of the workshop’s second period.

The collection also includes a set of Japanese ivories, with significant numbers of okimono, which are distinguished from netsuke by their size. These are objects intended for the export trade that evoke daily life in Japan. A representation of Madame Butterfly is particularly interesting. Chio chio-san holds a boat in her hand, a suggestive evocation of her situation, abandoned carrying the child of her lover Pinkerton, who has returned to America. We encounter evocations of the deity Kannon in his classical and esoteric aspect, small trades, such as a cormorant fisherman, a fan painter, or even a basket maker. Childhood is also a significant theme. These ivories are now presented, for the most part, in the library of Château Borély.

Hard and soft stone objects form another aspect of the collection. What is considered in China as jade actually includes stones of different affinities, such as jadeite, nephrite and steatite. The inventory employs the generic terminology. Note the polished character of these pieces, which links them to the Ming (明) [1368-1644] and Qing (清) [1644-1911] dynasties. Small urns on pedestals, archaic in shape, and libation cups mainly make up this set. A statue, remarkable for the finesse of the details, represents the Buddha Amitayus. The statue is adorned with jewels, girded with a crown, and seated in padmasana, his hands joined in dhyana-mudrâ.

Finally, Cantini had a sizeable collection of bronzes and cloisonné enamels. During the reign of Qianlong (乾隆) [1711-1799; r. 1736-1795], cloisonné received renewed interest and from that time on constituted an important export item. The specificity of the bronzes collected is undoubtedly based on the diversity of the coloured backgrounds. A pair of zun (尊) type vases that develop a "sample" motif on a pink background and are marked by a weft of swastika wanzi wen (卐子紋), indicate a recent period. Another piece commands attention for its imposing size: an incense burner mounted on bronze, with a lid surmounted by a dragon, in copper alloy.

Jules Cantini collected as an aesthete, without regard for the age of the objects. Most of the pieces date from the 19th century and were produced for export, as indicated by their large sizes. It is clear that there was a marked preference for sculpted objects, which are no doubt reminiscent of the collector's profession.

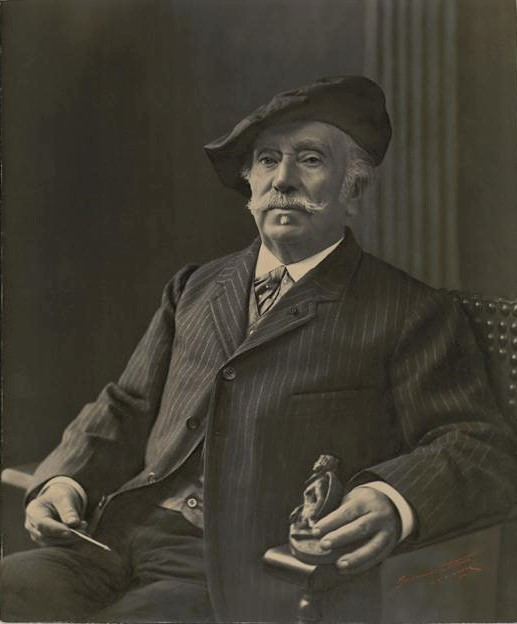

Anonyme

Ca. 1936

Martin-Duby, « Le Musée Cantini », Marseille, octobre 1936, n° 1, p. 18.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne