JACQUEMART Nélie et ANDRÉ Édouard (EN)

Biographical article

Nélie Jacquemart and Édouard André were an unlikely couple, a Catholic woman portrait painter and the Protestant heir to a banking fortune. Their marriage was arranged under dramatic circumstances: as André’s health was failing, his family sought to save him from exploitation and scandal (Sainte Fare Garnot N., 2011, p. 7). The couple’s relationship gave rise to one of the most notable private art collections of fin-de-siècle Paris.

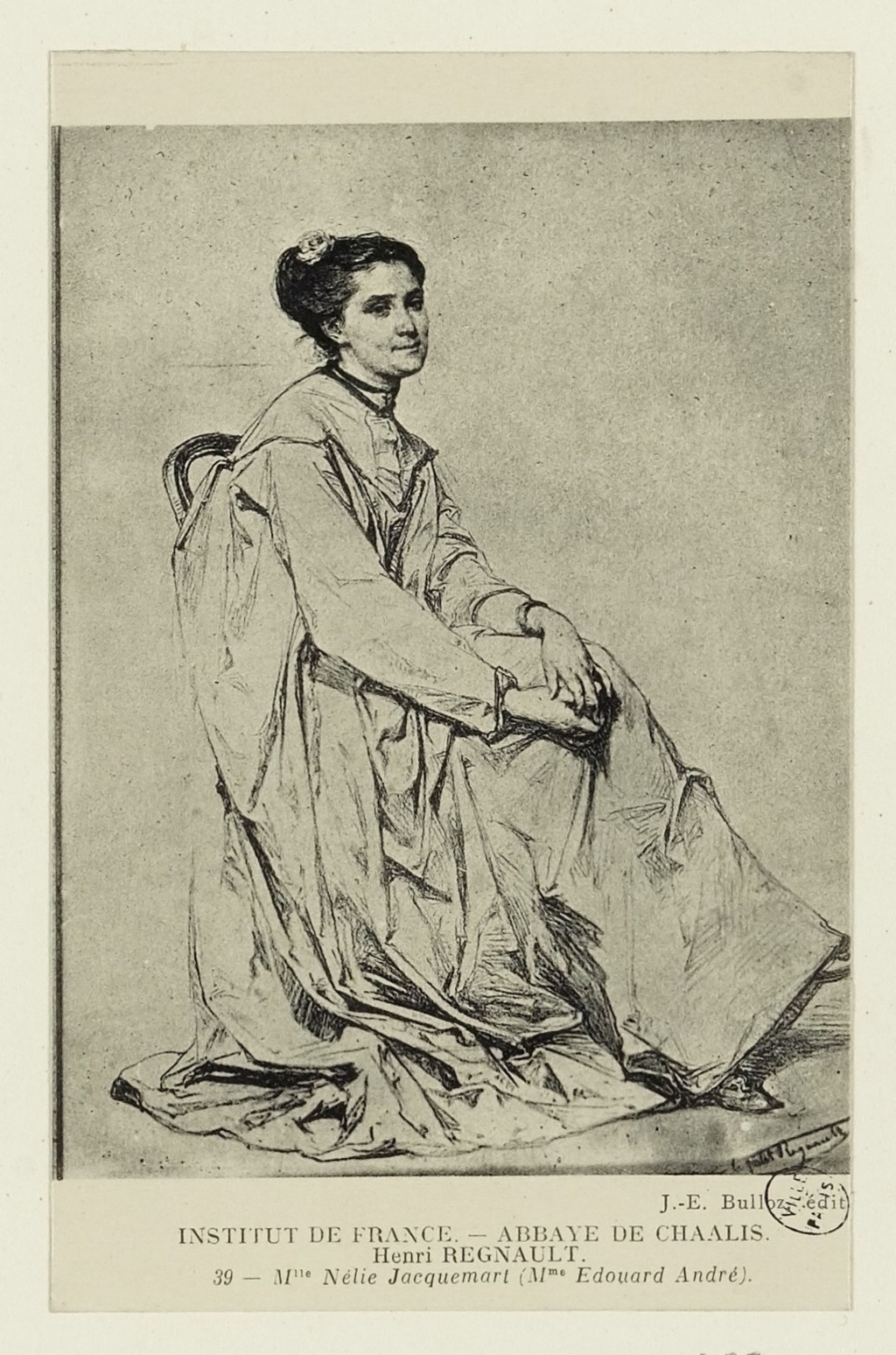

Nélie Jacquemart

Not much is known about the circumstances of Jacquemart’s birth or the origins of her personal fortune. She was born to Joseph Jacquemart and Marie Hyacinthe Rivoiret on 25 July 1841. Her father may have been the electoral agent of parliamentarian Alphée Bourdon de Vatry (1793-1871), who maintained a residence at Chaalis at the time (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 81). The proximity between the Jacquemart family and the Vatrys, and particularly the interest and affection Paméla Hainguerlot de Vatry (1802-1881) showed towards Nélie Jacquemart have given rise to colourful speculation. It has been suggested that Jacquemart may have, in truth, been the illegitimate child of Monsieur de Vatry, as it was well known in Parisian society that Madame de Vatry could not have children of her own (Sainte Fare Garnot, 2011, p. 6). Some local historians have even suggested familial ties to a prince d’Orléans with whom Nélie always entertained close relations (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 44). In the absence of any evidence supporting either theory, the only certainty is Nélie’s close relationship with Madame de Vatry, who took the young woman under her wing and encouraged Nélie’s interest in painting.

When Nélie was 16 years old, two lithographs co-signed by herself and established artist Léon Cogniet (1794-1880) appeared in the periodical L’Illustration (1858). Taking the opulent funeral of Malka Kachwar reine d’Oude as their subject, these pieces foreshadow Jacquemart’s later interest in India and the Far East. Shortly thereafter the Goncourt brothers begin to refer to her as “la peintresse” (de Goncourt E., 1891, p. 167).Jacquemart first submitted to the Salon, the official annual exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, in 1863. The following year, she also taught at a Paris drawing school. At the same time, her artistic career continued to progress with state commissions for decorative work at a number of Parisian churches (Babelon J-P., 2014, p. 46).

Painter Ernest Hébert (1817–1908) must have noticed Jacquemart around this time. He invited her to Rome in 1867 to see the Villa Medici. In Italy, Jacquemart struck up a close friendship with Geneviève Bréton (1849-1918), whose diaries, faithfully kept throughout her life, paint a portrait of Jacquemart as a “determined young woman” who wanted to “be someone” (Bréton G., 1994). Yet, the diaries also illustrated the resistance Jacquemart faced from Parisian high society, including from Bréton’s family, who saw Nélie as “too much of an artist” and regarded her modest origins with disdain (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 54). The twin experiences of the splendours of Italy and the snobbish exclusivity of the Parisian aristocracy are telling when we consider how Jacquemart invented an aristocratic Italian bloodline for her deceased mother, commissioning a plaque with the name San Bernardi di Rivori in her memory (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 52).

Throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s Nélie continued to celebrate significant successes in her painting, winning medals at the Salon each year from 1868 to 1870. The juries praised her “vigour and a frankness rare among women artists” and professed that her “name cannot be ignored…This portrait…places her in the first row” (Lafenestre G., 1914, p. 785). These academic successes were followed by a turn towards portraits as the mainstay of Jacquemart’s work. Her portraits of important statesmen at this time included the likes of the Maréchal de Canrobert (1809-1895) in 1870 and president Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) in 1872 – as well as her future husband Édouard André that same year. The painter’s last professional venture before her marriage would be the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where she exhibited six works and was awarded with a medal (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 83.).

Édouard André

The power and wealth wielded by the André family is well known to historians (Monnier V., 2006). The family’s first trace appears in 1433 in the Hameau de Laval, in the Vivarais region of south-eastern France. In 1600 they relocated to Nîmes, an important centre of Protestantism, as well as the silk and hosiery trade. Jean-Jacques André, a member of the Académie de Nîmes, began the tradition of buying art that would be passed down in the family with notable names like Tiziano Vecelli (1488/90-1576), Antonio da Correggio (1489-1534), Pierre Subleyras (1699-1749), and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) (Monnier V., 2006). Further family branches established themselves in Genoa, specialising in maritime loans and currency exchange, and in Geneva as bankers. In the 18th century the Andrés also created outposts in Naples and London, then in Lyon and finally in Paris in 1774 (Babelon J-P., 2012,p. 12.). The family financed some of the great national projects of the day, such as the Paris-Lyon railway line, the founding of the Orléans Railway Company and even the Suez Canal project (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 18).

Born to Ernest André (1803–1864) and Louise Mathilde Cottier (1814-1835), who was the daughter of wealthy banker François Cottier, on 13 December 1833, Édouard was set to inherit significant fortunes from both sides of his family. After his mother’s premature death in 1835 Édouard was raised by his father’s second wife, Aimée Louise Gudin (1812-1877), with whom he shared an affectionate relationship.

Considering the Bonapartist milieu of Édouard’s familial background, it is not surprising that he chose to enter French military. In 1852, he enrolled in the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, founded by Napoleon in 1802. Four years later, he was assigned to Napoleon III’s prestigious Imperial Guard. Citing familial reasons, André resigned in 1859, although he briefly returned to service in 1863 to participate in the Second French Intervention in Mexico (Monnier V., 2006).

After his father’s death, Édouard took over his father’s seat as representative of Le Gard, a protestant stronghold. Upon France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, however, the Second Empire dissolved into the Third Republic, and André turned away from public life. Besides his frequently cited disappointment, it is likely that his waning health further contributed to André’s turn to private collecting at this time; it was well known in Paris that he suffered from syphilis (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 20; Cilmi G., 2020, p. 48).

In these early years, Édouard primarily acquired art at large public auctions, and he lent his collection to exhibitions organised by the Union Centrale des Beaux Arts Appliqués à l'Industrie in 1863, 1865, and 1877. After years of involvement in the Union Centrale, he was elected its president in 1872 and purchased the influential Gazette des Beaux-Arts the same year, placing him at the centre of the French arts establishment.

During this period of early acquisitions, André embarked on a second project: the construction of a mansion on the Boulevard Haussmann. Celebrated architect Henri Parent (1819-1895) received the commission and building works started at the end of 1868, to be largely concluded in 1870. The war and siege of Paris interrupted the project, which meant that decorative works were only completed in 1874, the same year an organ was installed in the mansion. Enthusiastic about music, the Jacquemart-Andrés hosted some of the most celebrated musicians of their day, including Claude Debussy (1862–1918) and Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924).

1881: the Jacquemart-André union

Nélie Jacquemart and Édouard André met in 1872, when Nélie was commissioned to paint Édouard’s portrait, but an archival document only discovered recently reveals that they had stayed friends in the nine years between the commission and their wedding in 1881 (Cilmi G., 2020, p. 48). The marriage was likely arranged with the help of Édouard’s uncle Maurice Cottier (1822-1881) and his cousin Alfred-Louis André (1827-1893) after Édouard’s health had deteriorated. A desperate letter by one of Édouard’s friends recounted André’s serious condition and the exploitation he suffered at the hand of his mistress (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 36.).

To rescue Édouard from this dire situation, the marriage arrangements with Jacquemart were made within a short period of 15 days (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 87). As the André family was not only concerned for Édouard’s well being but also for the fate of his fortune, the marriage contract stipulated a strict separation of property between the spouses. In return, Nélie was granted 100,000 francs after her husband’s death to ensure her livelihood (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 56). Despite Édouard’s gift of a painting studio for Nélie on the first floor of his mansion, Nélie decided to stop painting altogether and turned to collecting as her primary occupation.

An inventory of her property before her union with Édouard illustrated her early collecting activities and foreshadowed the kind of objects she would go on to amass: paintings, antiquarian books, Renaissance furniture, Cordoba leathers, Persian rugs and Hispano-Moresque pottery, Etruscan, Egyptian, Chinese and Japanese objets d’art. Although her collection was small, it was intentional and differed significantly from Édouard’s own personal collection that comprised contemporary French painting with a few Italian, Dutch, and Flemish masters (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 56).

One year after their wedding, Nélie and Édouard’s lives and collections began to cohere, as Nélie joined the editorial board of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, a highly unusual position for a woman at the time. That same year saw the couple’s first journey to Italy, marking the beginning of collecting voyages around the world. In 1888 one of their travels took the couple to St Petersburg, where Nélie, was invited to exhibit her works with the Red Cross. She participated with eight of her most representative works, including the portraits of her husband, Thiers and Duruy (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 85).

Despite the family’s efforts to prevent Nélie from accessing the André fortune, Édouard amended his will on 9 July 1890 and made his wife his sole heir, thereby dissolving the original marriage contract (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 61). Along with this increased personal cohesion, the couple’s collecting became more unified. The idea of an “Italian Museum” in their mansion, directed by Nélie, began to gain traction (Cilmi G., 2020, p. 49). As a further testament to the couple’s shared life and mission in completing their museum, Édouard authorised Nélie to access his personal bank account on 21 May 1894 (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 9; Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 92). Two months later, on 16 July, Édouard finally succumbed to illness. Distraught, Nélie departed for Switzerland and for the following three years her collecting slowed amid a legal battle over Édouard’s will, which she would go on to win (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 61).

The final objective of the Jacquemart-André collection and fortune was decided in 1900, when Nélie bequeathed it all to the Institut de France on condition of turning her home into a museum. Yet her collecting days were far from over. She pushed the boundaries of her existing marital collection, but also returned to collecting art she had been interested in since her youth, particularly art from the Middle and Far East. In 1902 she left Paris for an adventurous journey from Marseille to Port Said, Colombo, Kandy, Ceylon, Madras, Darjeeling, Calcutta, Delhi, Agra, towards and Peshawar and finally Bombay (today Mumbai) (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 95). On excursions to local archaeological sites, Nélie never failed to think about her collection and bought antiques. When originals were unavailable she was offered copies and the Francophile Maharaja of Kapurthala, Jagatjit Singh (1872–1949), who hosted her, even presented her with replicas of his personal furniture, alongside a promise to visit her in Europe – a promise he would keep (Stammers T., 2020, p. 49). Nélie was also particularly taken with the ancient city of Bagan and Rangoon (today Yangon), where she visited the same antique dealer multiple times a week throughout her stay (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 96).

She hoped to extend her journey to China and Japan, planning to depart for Yokohama on 7 April 1902, but a significant portion of Nélie’s correspondence during this period betrays her preoccupation with the Chateau of Chaalis, the home of her former patron, Madame de Vatry. The chateau was offered for sale at the time and Nélie was anxious to buy it. Thus she returned to France and abandoned her plans to travel to China and Japan. After becoming the new owner of Chaalis on 14 June 1902, she immediately occupied herself with renovating and modernising the chateau and its outbuildings and preparing the space for her collections (Verlaine J., 2014, p.62).

All the while, neither Nélie’s travel nor her art collecting subsided. She purchased art in Cairo, Constantinople, Damascus, and Beirut. In 1910 Nélie made her way to Spain and then to Switzerland, again enlarging her collection. In early 1912, she finally returned to her beloved Italy, spending the first quarter of the year procuring art. However, these final acquisitions would only arrive in Paris after her death on 14 May 1912, robbing her of the opportunity to arrange them for display herself (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 106).

Her funeral was grandiose and the guests included six members of the Orléans family, the Under-Secretary of State for Fine Arts, five ambassadors and thirteen members of the Institute de France, which received the collection, the mansion on the Boulevard Haussmann, Chaalis and its land, and an endowment of 5 million francs to cover the costs of operating the museum (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 63).

Art historian Louis Gillet (1876–1943), a future member of the Académie Française, took over the curation of Chaalis, while Georges Lafenestre (1837-1919), curator at the Louvre, was charged with the care of the Boulevard Haussmann (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 119). As museum director, Lafenestre proposed the esteemed art history professor Émile Bertaux (1869-1917). Bertaux’s most important contribution to the new museum would be the original catalogue (Bertaux É., 1913). With the academic leadership decided, the Musée Jacquemart-André, a name chosen by Nélie Jacquemart to reflect her important contribution, opened on 8 December 1913. It was inaugurated by Raymond Poincaré (1860- 1934), the President of the French Republic.

The collection

France and the Low Countries

French imperialism and a celebration of the Second Empire underscored the Jacquemart-André collection. Nostalgia for the 18th century inspired the Bonapartist Édouard and the Orléanist Nélie to recreate aristocratic France in miniature in their home. They circumscribed empire through paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and furniture. Before marrying Nélie, Édouard had purchased several contemporary French paintings (Lafenestre G., 1914, p. 781). However, Nélie’s influence led to the resale of these canvases. In 1865 – well before Nélie’s entrance in his life – Édouard turned to the 18th century with acquisitions of Jean Germain Drouais (1763-1788), Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805), Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1758-1823), Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (1780–1850), and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) and thus laid the foundation for their joint collecting (Babelon J.-P., 2012, p. 31).

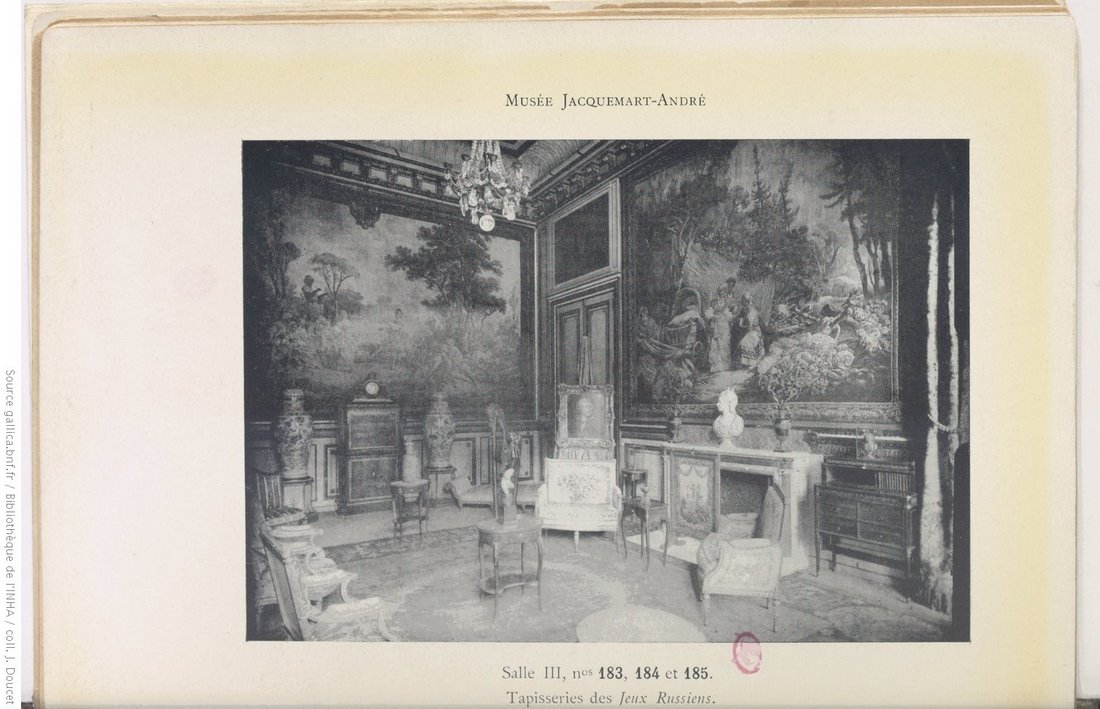

Tapestries from the traditional French Gobelins and Beauvais Manufactories complemented the paintings. Of particular interest is one example from the New Indies series, based on designs by Alexandre François Desportes, from around 1730 (Institut de France, 2012, p.7). These types of tapestries primarily appeal to exoticism, containing colourful costumes, and unfamiliar landscapes. They “generally revealed little respect for geographical and ethnographic accuracy, their main aim being to express pride in French exploration and in the hold of the Bourbon monarchy over its colonial territories and trading bases” (Walsh L., 2017, p. 174). It is worth noting that the flora and fauna depicted betrays an obvious confusion between the “Old” and “New” Indies, again, highlighting the symbolic importance of the pieces as a testament to splendid empire (Walsh L., 2017, p. 174).

Édouard and Nélie pursued an atmospheric aesthetic of refined splendour and were less interested in an academic or chronological display. Therefore, they chose their furnishings to harmonise with the art on display. The study in the Boulevard Haussmann, for instance, contains a selection of 18th- century paintings and also houses a set of four carved giltwood armchairs, signed “Jacques Chenevat (1736-1772), master craftsman, 1763”. The chairs were upholstered with tapestries from the aforementioned Beauvais Manufactory (Jacquemart-André Museum: Official Guide, 2012, p. 17). The room also houses a desk and numerous chests, decorated with Japanese and Chinese lacquer respectively and evoking the 18th-century French fashion for Chinoiserie. The desk was signed by Jacques Dubois (1694–1763), Louis XV’s cabinetmaker and a pair of corner cupboards in Vernis Martin have been attributed to 18th-century cabinetmaker Jean Déforge (?-after 1757) (Jacquemart-André Museum: Official Guide, 2012, p. 17f.).

At first glance the Dutch and Flemish pieces in the collection may seem out of place in the Jacquemart-André collection. But considered alongside their French counterparts, they could be seen as inspirations for the French art Édouard favoured (Institute de France, 2012, p. 25). Yet it is also possible that the couple considered these masters central to the history of beauty and therefore indispensable to a full collection.

Italy

Once the couple started seriously considering the idea of an “Italian Museum”, their collecting intensified further. Primarily focussing on the Quattrocento, Venetian and Florentine works took centre stage. Édouard and Nélie acquired everything from an enormous Tiepolo fresco, paintings, sculptures in various media, to earthenware medallions and other smaller objets d’art. Nélie also favoured religious themes and created an ecclesiastical atmosphere in the Florentine Gallery on the first floor at the Boulevard Haussmann. Early 16th-century choir stalls are flanked on both sides by 15th and 16th century Italian stone doorways. Above the stalls, the stone tomb of an Italian nobleman creates a pious serenity. Numerous depictions of the Virgin and Child and one imposing church altarpiece adorn the walls (Babelon J-P., 2012, p. 78; Institute de France, 2012, p. 41). In reference to her affinity for religious themes and her sexless marriage, Parisian society cruelly called Nélie la Vierge à la chaise (the Virgin of the Chair), an allusion to the famous Raphael painting (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 56).

The push for an Italian collection originated with Nélie, who corresponded with art dealers in the first person singular, effectively excluding her husband (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 90; Verlaine J. 2014, p. 60; Cilmi G., 2020, p. 51). From her correspondence, the image of a conscientious collector emerges. She valued authenticity and quality and placed a premium on “antique” objects. To ascertain whether objects were genuine, she turned to her acquaintances in the museum world for advice. If, for instance, Wilhelm von Bode (1845 –1929) of the Royal Museums in Berlin or Louis Courajod (1841-1896) of the Louvre doubted the authenticity of her acquisitions, Nélie did not hesitate to return them and demand her money back. Nélie also envisioned a special file containing this correspondence with curators as a reference archive for the eventual museum to be established in the Jacquemart-André residence (Cilmi G., 2020, p. 66).

The relationship between the Jacquemart-Andrés and professional art historians was usually one of friendly competition when it came to buying art. With French curators, however, they shared a special desire to secure the world’s best pieces for France. This patriotism informed the couple’s wish to leave a legacy of the highest quality to the French people, as Nélie wrote in her will. The same patriotism inspired the collectors’ efforts to export some of their most valuable acquisitions from Italy despite resistance from the newly established Italian nation (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 60). For instance, the couple’s preferred Italian merchant Stefano Bardini (1836–1922), also known as the principe degli antiquari, significantly underdeclared the value of art purchased by the couple to circumvent strict export regulations (Cilmi G., 2020, p. 58).

Their insistence on collecting treasures around the world for the benefit of France was not unusual. The turn of the 19th century was characterised by a spirit of national rivalry, where primacy in Europe was not only established on battlefields, but also on exhibition grounds and in museums. Lafenestre highlights the fact that France lagged behind the British South Kensington Museum and the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna and needed to catch up. Édouard and Nélie believed that if the state lacked the will or funds to install a collection of the required calibre, the task fell to private collections (Lafenestre, 1914, p.772).

England, Egypt and the Near East

Nélie continuously pushed the boundaries of the couple’s collection beyond Italy, especially after her husband’s death. In 1895, the new widow travelled to London to purchase art at auction, something she rarely did, usually preferring to buy from individual art dealers. Not only the mode of acquisition was unusual on this occasion. For the first time, she now introduced English art into the collection, acquiring a series of portraits by Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Joshua Reynolds 1723-1792), and Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) (Institut de France, 2012, p. 33; Verlaine J., 2014, p. 62).

While Édouard and Nélie travelled frequently as a couple, it is likely that these journeys were far from carefree. Due to Édouard’s medical condition their mobility was limited and several journeys had to be modified or cut short. After his death Nélie ventured further and further afield, following her own personal taste and redefining the contours of the Jacquemart-André collection (Verlaine J., 2014, p. 52). Trips to Egypt and the Near East proved to be fruitful for the collection and allowed Nélie to integrate new acquisitions inro the existing collection to form “ensembles”. In these ensembles, she did not arrange objects by art historical or ethnographic themes but pursued a more ephemeral ambience. In her “Smoking Room”, for instance, she combined her recently acquired English portraits with a 16th-century Venetian marble fireplace, and decorated the room to achieve an “oriental” atmosphere. This was achieved through Iranian and Ottoman carpets, a pair of Chinese cloisonné vases, an Indo-Portuguese cabinet, and an enamelled glass mosque lamp (Institut de France, 2012, p. 33). A popular display method, the central aim of such ensemble rooms was to evoke joy and wonder, rather than academic art appreciation (Péladan J., 1914). For that reason, it was shunned by later curators, anxious to emphasise the academic order, only to be restored by the Bautiers in 1993 (Babelon J-P. and Vasseur J-M., 2007, p. 56).

China and Japan

Like her Islamic collections, a small number of Chinese and Japanese objects, primarily ceramics and cloisonné enamels, a silk tapestry, and an 18th-century panelled screen were preserved in the Boulevard Haussmann and at Chaalis. Nélie’s inventory of personal property, drawn up for her marriage contract with Édouard, indicates that she had developed an interest in the Far East and its art early in life. Perhaps her modest standing when she first began acquiring non-Western pieces overshadowed their art-historical significance. As a result, just like the Near Eastern objects in the collection, these East Asian pieces and their provenance have not yet been adequately studied and at present remain little more than aids in the creation of an 18th-century Orientalist décor.

India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar

The objects Nélie obtained in Southeast Asia are different. Because she purchased scores of objects (notably Indian and Sinhalese arms and armour, musical instruments, ancient wooden altars, Isfahan and Shiraz rugs, chests, and objets d’art), dating largely from the 18th-century, in person during her voyage on the Indian subcontinent in 1902, it is safe to assume that these acquisitions meant more to her than aesthetic decoration. She is especially enchanted by Colombo and Kandy, but does dwell on details of the cultures and objects she sees in the letters she sent to her staff back in Paris, safe to communicate her delight at everything. In a letter dated 17 February, Nélie shares her enthusiasm for Rangoon, where she visited archaeological sites, such as Bagan. Here she acquired what she referred to as antique and medieval pieces, and which would later find a permanent home in Chaalis. It appears that she was particularly taken with Burma, where she made repeated visits to the same antique dealer in Rangoon (sometimes multiple times a week). In her letter home she announces the arrival of a case of objects, all over 300 years old, from said dealer and instructs her staff not to open the chests, as she intends to arrange all displays herself. After her return and the purchase of Chaalis, this is exactly what she does, creating an Indo-Burmese room in chateau, which will be dismantled and used as a studio by later curators of the museum (Bautier A. and Bautier R., 1995, p. 96).

In addition, the Maharaja of Kapurthala brought her a generous set of golden Buddhist sculptures on the occasion of his visit to Chaalis around 1905 (Babelon J.-P. and Vasseur J.-M., 2007, p. 56). However, only a full study of her archives, particularly correspondence and invoices regarding these purchases could illuminate her interest and knowledge. The Maharaja of Kapurthala’s personal diaries and correspondence, which are still extant, might offer another potential avenue into the history and significance of this extraordinary Southeast Asian collection.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une famille

Personne / personne

Personne / personne