DIETRICH Albert de (EN)

Biographical Article

Engineer, soldier, author, lecturer, archeology enthusiast, collector, donor and above all a committed patriot, the diversity of hats worn by Albert Louis Eugène de Dietrich (1861-1956) is matched only by the eclecticism of his collection, a reflection of these various facets of his life. It began in Niederbronn, Alsace, on August 26, 1861. His parents, Sophie Louise Amélie Euphrosine de Dietrich née van der Thann-Rathsamhausen (1825-1890) and Albert Frédéric Guillaume de Dietrich (1831-1909), belonged to a dynasty of major industrialists in the field of metallurgy, whose surname was also famous thanks to certain members, like Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich (1748-1793), first mayor of Strasbourg at whose home the Marseillaise was sung for the first time, a famous episode which had something to do with the family's political commitments.

From Alsace to South America

At the age of nine, Albert Louis Eugène watched the battle of Woerth-Froeschwiller from the ruins of Wasenburg castle where his father had sheltered his children (Archives de Dietrich (ADD) GDD 98/1), an experience that made a lasting impression (see Dietrich A. de, November 1-15, 1918, p. 349). At seventeen, the young man was emancipated so that he could attend the board meetings of the family business (ADD GDD A98/13). Like most of his ancestors, he studied to become an engineer at the École centrale des mines. At the age of twenty-one, his political convictions led him to opt for French nationality, which was granted to him by decree of October 14, 1882 (AN BB/27/1242/3), and he then had to leave his native land and his family. This event marked a turning point in his life as he decided, as the Baron himself recounted it, to travel across the Atlantic, moving between Peru, Bolivia and Chile from 1888 (Dietrich A . de, n.d., pp. 24-25). He offered to represent the company in South America (ADD carton 97a) and took charge of prospecting for the construction of a railway line through the Atacama desert, between Antofagasta in Chile and Augusta Victoria in Bolivia, the plan of which is kept in the Dietrich archives at Reichshoffen castle (ADD XIV/1-16.019). This distance prevented him from ever again seeing his mother who died in 1890. During his journey, he collected a large quantity of archaeological objects which he decided to donate in 1894 to the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, explaining the circumstances of their discovery in a letter to its director (MQB D002860/40710).

Léonardsau, the "Castle" of Albert de Dietrich

The exact date of his return to France is not known, but a letter from his father attests to his presence in Paris in September 1892 (ADD, s.c.). Two months later, on November 5, in Boissy-Saint-Léger, the thirty-year-old married Marie Louise Lucie Hottinguer (1870-1961), the daughter of Baron Rodolphe Hottinguer, regent of the Banque de France, belonging to the Protestant upper middle class of the financial world in Paris (AD 94 1MI 2373). After the wedding, the baron left the business of De Dietrich et cie. In 1897, he no longer held any shares in the company (ADD A-II/2) before buying two in 1898, almost symbolically, which made him the smallest shareholder and allowed him to participate in the meetings of the board of administration, which he occasionally did. He was even appointed the shareholders’ delegate from 1905 to 1908 (ADD Carton A-V/1), without ever taking on a greater responsibility than this. Living on his income, he changed his place of residence several times: from 20 rue Louis Legrand in the 2nd arrondissement, to 78 rue de Monceau in the 8th arrondissement, and finally to 82 boulevard Malesherbes, at the same address as his parents-in-law. He tried to return to Alsace several times and was expelled twice (ADD, s.c.). Nevertheless, he managed to settle there at the end of the 1890s, as evidenced by the purchase in 1896 of land from the Coulaux company, located in Saint-Léonard, in a small town of Boersch, in the Bas-Rhin (Ameur M., Gressier E., Metz-Schillinger S., 2007, p. 67). From 1899, he had a house built there in the neo-regionalist style, the plans for which were initially entrusted to the architect Louis Feine (1868-1949) before undergoing several alterations (Harster D., 1983, n.p.). The garden was designed by Édouard André (1840-1911), a renowned landscape architect who participated notably in the planting of the Buttes Chaumont park in Paris (Courtois, S. de, 2020), and his collaborator Jules Buyssens (1872- 1958) who later became inspector of plantations for the city of Brussels (Bruyn O. de, 2017). The interior decoration was entrusted to Alsatian artists, such as Charles Spindler (1865-1938). Albert de Dietrich was personally involved in the project down to the smallest detail, as evidenced by the letters he wrote to Charles Spindler, undecided as to the color of the fabrics to put on the walls of each room, and not hesitating to add his own pencil strokes on the plans of the park. The estate as a whole was marked by the very eclectic tastes of its owner. Its green bower, decorated with sculptures and furniture from various periods, was translated into different atmospheres, from the Japanese garden to the Alpine stream, while the residence’s facade was adorned with many reused elements and its interiors were populated with various objects. The entire estate served as a backdrop for festivities testifying to Baron de Dietrich’ imagination, such as the evening that took place on the “21st day of September of the year of Grace 1535 at precisely nine o'clock at Chastel de Léonardsau during which the legend of Saint Odile, patroness of Alsace, was performed” (Hébert A., 2001, vol. 2, p. 117). Albert de Dietrich also offered his personal presence by interpreting plays with his guests or by inventing pantomimes (Ferrari, 1905, p. 2).

For a French Alsace

At the start of the First World War, the Baron entrusted the care of his "castle" to Charles Spindler, his neighbour, who shared his pro-French political opinions. True to his convictions, he enlisted in the French army as an interpreter-officer at the General Staff of the Tenth Army. At the same time, he became a lecturer and wrote propaganda booklets in which he did not hesitate to summon the history of his family and to rearrange that of the region to legitimise his belonging to French territory. These little booklets bear evocative titles: Au Pays de la Marseillaise (Dietrich A. de, 1919), La création de la Marseillaise : Rouget de Lisle et Frédéric de Dietrich (Dietrich A. de, 1918), Alsaciens, Lorrains, nos frères ! (Dietrich A. de, 1918), Lorraine, Alsace… Terre promise ! (Dietrich A. de, 1918), translated into English (Dietrich A. de, 1918), and finally Alsaciens, corrigeons notre accent (Dietrich A. de, 1917). He obtained several decorations rewarding his commitment: first the Croix de Guerre, then the légion d’honneur by decree of July 12, 1919 (AN 19800035/137/17382). Despite the constant occupation of the Léonardsau throughout the conflict by several staffs - from Württemberg, Prussia, and even Hungary (Spindler C., 2008, p. 56-57 and 764-765) -, and the announcement of its liquidation as an emigrant’s property (AM Strasbourg 78Z86), its owner was able to return to it upon his return from Alsace to France.

But the Baron's commitment did not end with the war. On July 14, 1922, he spoke as president of the Marseillaise committee, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Marseillaise monument on Place Broglie in Strasbourg (BNF, EI-13 2721 and EI-13 918), which was sculpted by Alfred Marzolff (1867-1936), an artist who belonged to the circle of Saint-Léonard. Albert de Dietrich's donations to the museums of Strasbourg in 1924, 1929 and 1930 should also be seen as committed gestures since the collections had been badly damaged during the last two wars and curators such as the charismatic Hans Haug (1890-1965) were seeking to replenish the walls. The challenge was also to make up for the delay in the acquisition of French and Alsatian works after almost fifty years of cultural policy centred on Germany (Office municipal de statistiques de Strasbourg, 1935, p. 915). These donations were also made at the time of work carried out at Léonardsau and the appearance of new addresses by Baron de Dietrich in the Bottins mondains. We thus learn that he owned a residence in Strasbourg, 1 rue Joseph Massol and, in the 1930s, the villa Araucaria in Cannes, avenue de Bénéfiat. Very different from the tastes he expressed at the Léonardsau, the building was in the Art Deco style, designed by the architects Emile Molinié, Charles Nicod and G. de Montaut on behalf of the Société Française Immobilière in 1925 (Fray F., 2007) .

When the Second World War broke out, the baron was nearly eighty years old. When the glorious statue of La Marseillaise was destroyed by a Nazi youth organisation, part of his collection was seized. However, he had time to put his works in the cellars of the chateau of the Andlau family (Goepp J.-C., 2009, p. 15), his longtime friends. A proof of his determination to protect his collection is the testimony collected by Annabelle Hébert, unfortunately not transcribed, of Mrs. Welker, a domestic worker at the Léonardsau in the 1950s, which recounts the discovery, several years after the end of the conflict, of a statue of a saint hidden behind the face of a wall (Hébert A., 2001, vol. 2, p. 54). At the end of the war, Albert de Dietrich recovered most of his collection, which were largely sent to the museums of Strasbourg which, having become French again, benefited from two new donations in 1950 and 1952. On the other hand, the baron had to part with the Léonardsau, which had suffered too much during the war, when it housed an annex of the Nachrichtenschule SS in Obernai as well as a nursery (Braun J., 1974, p. 158). Its new owner did not seem to have been chosen at random, as it was General Raymond Gruss (1893-1970), a veteran of the First World War and a commander during the Second of an armoured division during the landing in Provence in August 1944 (Braun J., 1974, p. 158). The house, in very poor condition, is now the property of the city of Obernai. Baron de Dietrich died on April 25, 1956 at 82 boulevard Malesherbes in Paris and bequeathed a few family souvenirs to the Strasbourg historical museum. Lucie de Dietrich perpetuated the memory of her husband by in turn making several donations in his name between 1959 and 1961.

The Collection

Like a large number of collections, the one assembled by Albert Louis Eugène de Dietrich is no longer possible to imagine in its entirety today. The clues allowing us to reconstruct its composition are rare apart from the inventories of the museums to which the Baron and the Baroness saw fit to entrust certain objects, the number of which amounts to just over 220. They are now dispersed between the Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac museum in Paris, successor of the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro; the musée municipal de Saint-Dizier; and eight Strasbourg museums (the musée Zoologique, musée Archéologique, musée Historique, musée des Beaux-arts, musée des Arts décoratifs, cabinet des Estampes, musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame and the musée d’Art moderne et contemporain). The whole collection is characterised by an eclecticism at all levels, from the typology of the objects collected, their uses, and their manufacturing materials to their geographical area of origin and their chronological period of creation. It includes both paintings on canvas, wood, paper or silk, drawings and prints, as well as ceramics (earthenware, porcelain, stoneware, terracotta), glassware, sculpture in marble, bronze or plaster, archaeological furniture made of wood, bone, glass, basketry or gourds, parts of fabric costumes, and even human remains. Like a collection around the world, it pays as much attention to regional Alsatian popular art as to objects from sources as diverse as France, Germany, Italy, England, Spain, Greece, Syria, Palestine, Chile, Persia, and China. As for its chronological broadness, it covers a period from antiquity to the 20th century (Weinling M., 2015, vol. 2, p. 68-123).

The Chiu-Chiu Mummies and their Trousseau

Although the chronology of the collection’s assembly remains incomplete, its very personal character makes it possible to link a certain number of objects to specific events or periods of the life of the baron. First, the Chilean artefacts seem to have constituted a separate youthful collection. Collected between 1888 and 1891 or 1892, it was donated in 1894 to the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. The objects that compose it were unearthed from the sands of the Atacama Desert "before [his] eyes" (MQB D002860/40710) and come, according to the baron's statements, from two tombs located near the village of Chiu-Chiu. They contained two mummies, one of a man, the other of a woman, surrounded by everyday objects such as clothes, sandals, pottery filled with corn, baskets, spoons, bows with their quivers and their arrows and elements of a loom or harness, forming a set of around 54 numbers currently kept at the musée du Quai Branly (inv. 71.1897.9.1 to 71.1897.9.54).

Family Souvenirs

In a second stage come the family memories, which were transmitted to Albert Louis Eugène by his family. They often belong to the 18th century, the golden age of the de Dietrichs, which saw Jean III Dietrich (1719-1795) being ennobled by King Louis XV and obtaining from the Emperor François I the designation of baron of the Holy Empire (Hau M., 2005, p. 21) and Philippe Frédéric de Dietrich becoming mayor of Strasbourg in 1790 and participating in the creation of the Marseillaise (Hau, 2007, p. 67). This last figure is often cited among these family relics, like the miniature portrait of his wife, Louise Sybille de Dietrich née Ochs, dated 1778 (Strasbourg Historical Museum, inv. MH 2976) or an engraving by Jean-Henri Eberts (1726-1793) after François Boucher (1703-1770) entitled Le tribut de la reconnaissance and dedicated "à M. le Baron de Dietrich" (cabinet des Estampes de Strasbourg, inv. LIX.43). The Freemasonic reticule given in 1805 by Baroness de Dietrich to Empress Josephine in Strasbourg on the occasion of her admission to the Lodge of Virtue (musée Historique de Strasbourg, inv. MH 2978) is also among the objects entrusted to the museum. They probably arrived in the collection relatively early, but were conversely among the last to enter into public collections, probably for sentimental reasons, as part of the bequest granted by the baron to the museums of Strasbourg handed over by Lucie de Dietrich in 1959 and the donations that she continued after the death of her husband. Albert Louis Eugène de Dietrich also wrote himself into the history of his family by donating artefacts personally linked to him, such as the medals published on the occasion of the erection of the Marseillaise monument representing Rouget de Lisle (Strasbourg Historical Museum, inv. 1413 to 1415) or his military costume from the First World War (musée Historique de Strasbourg, inv. CFK 1484 and 2199) as well as his decorations, which he entrusted to the collector Fritz Kieffer (1854-1933) for his “musée du Souvenir national”that brought together uniforms worn by Alsatians from the 18th century to the contemporary period, to the Historical Museum of Strasbourg on his death in 1933 (Schnitzler B., 2009, p. 192).

Albert de Dietrich and Florine Langweil: Two Patriots’ Shared Passion for Asian Art

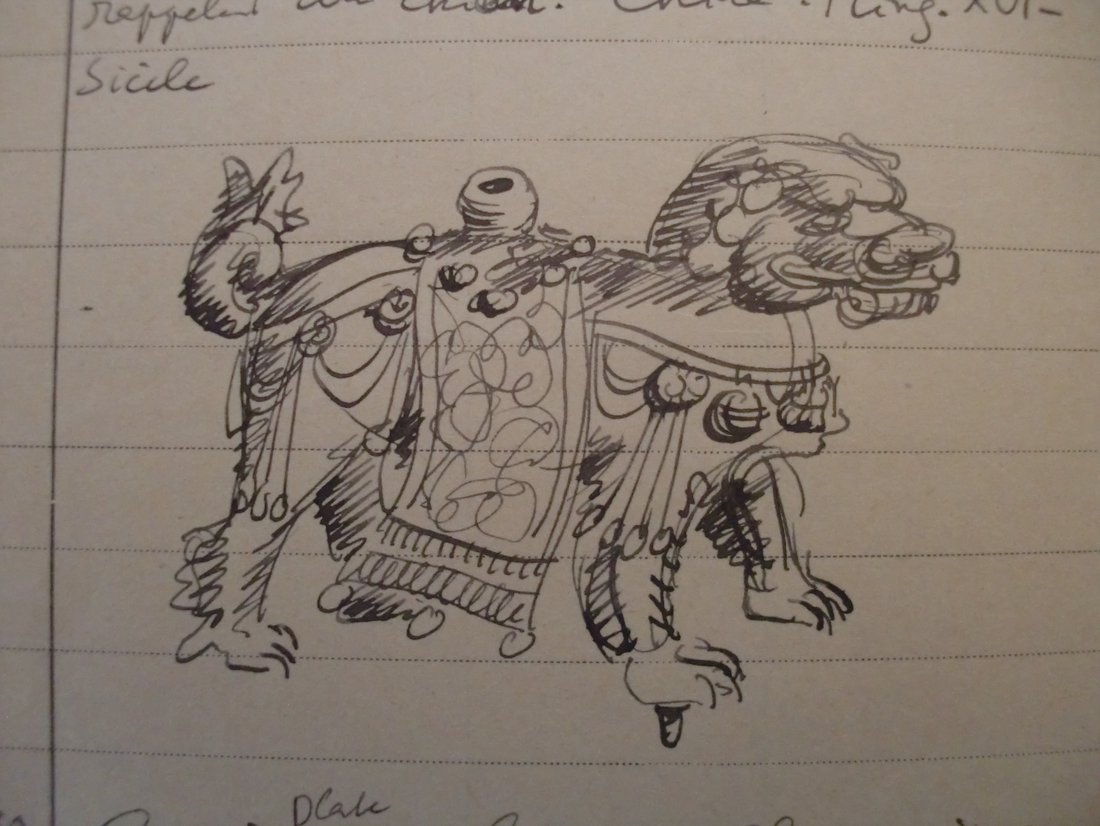

A third major category within the collection concerns Far Eastern art, almost exclusively Chinese, which represents 20% of the objects donated to museums by Baron de Dietrich. His taste for this type of work can be connected to his meeting the dealer Florine Langweil (1861-1958), from whom he made most of his acquisitions, as evidenced by the inventories of Strasbourg museums which regularly mention this provenance for purchases made around 1910. In addition to their age, these two figures had many things in common, including Alsatian origins, a residence in Paris, strong pro-French convictions stemming from family heritage, and a personal commitment to a French Alsace. In their actions as collectors, they made donations of similar objects to the same institutions, sometimes only a few months apart, as if driven by a feeling of emulation. Thus, Albert de Dietrich’s first grants to the re-Frenchified museums of Alsace, a set of twenty-six Persian miniatures (see on this subject Panozzo L., 2019) in 1924, came after the donation of three equivalent works by Florine Langweil shortly beforehand (AM Strasbourg 5MW233). The tastes of the two collectors, if not always following the same inclinations, had several points in common, such as a clear preference for Chinese objects and a shared interest in painting on silk and ceramics. The latter was particularly present in Dietrich's collection in the form of ridge tiles and statuettes, and in particular a mingqi depicting a horseman, from the Fang period to the 8th century (Strasbourg Museum of Decorative Arts, inv. XXIX/ 115). Paintings on silk, depicting animated landscapes, portraits and Buddhist scenes, were also numerous. On the other hand, bronze was very rare, with only two objects, including an incense burner in the shape of a fabulous animal reminiscent of a dog or a lion from Fo, dating from the Ming period in the 16th century. The baron did not seem to have shared his compatriot's taste for lacquered objects.

Less exclusive than Florine Langweil, Albert de Dietrich did not hesitate to mix Asian art with other objects, particularly from the European 18th century, and sought to create a more decorative effect, without excluding copies. If the place of exhibition of these objects is difficult to identify among the different residences of the de Dietrichs, some of them are recognisable on postcards and photos that represent the Léonardsau and its interiors (Spindler family archives, s.c.), which is also mentioned as the provenance of certain works included in the 1950 donation, when the estate was sold. The work carried out there in the 1920s also suggests that the complex abandoned to museums at this time also stems from its decoration. Eighteenth-century art and Oriental and Far-Eastern arts from all eras probably cohabited in this residence and served as the setting for parties, such as this evening in 1925 where an "elegant variety of Oriental costumes are mixed alongside marquises and marquises powdered in the court clothes of the old regime" ("Les Mondanités", 1925, p. 2). This event also gives a glimpse into the dream-like role that the Orient represented for the Baron, as evidenced, in the realm of dressing up, by a set of drawings by Léon Bakst (musée d'Art Moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg, inv. 1206 to 1208 and 1212 to 1214), that depict images of a memorable evening in 1913 spent in company of the Ballets Russes in a Parisian garden lit by multicoloured light bulbs (Vignaud, Bertrand du, 2003, p. 10).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne