ISAAC Prosper-Alphonse (EN)

Biographical Article

Originally from Calais, Prosper-Alphonse Isaac was born into a bourgeois family of lace makers. His father Augustin Isaac (1810–1869), a collector and amateur sculptor, gave him his taste for the arts, particularly of the Far East. At the end of the 1870s, Prosper-Alphonse Isaac left his birth region to train with the artist Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921) in Paris.

Isaac and the Circle of Japonisants

When Isaac moved to Paris at the end of the 1870s, Japonisme had already fully permeated the capital, and the young painter did not miss the many exhibitions devoted to Japanese art: "In Paris, his refined taste as a decorator was struck by the beauty that had been newly revealed by Japanese prints. He visited the print exhibition that Louis Gonse had put together at the Georges Petit gallery [in 1883]. I will never forget the enthusiasm with which he made new devotees at the magnificent exhibition that S. Bing organised in 1889 at the Grande Galerie of the École des Beaux-Arts,” testified Gaston Migeon (1861-1930) [Objets d'art du Japon, 1925].

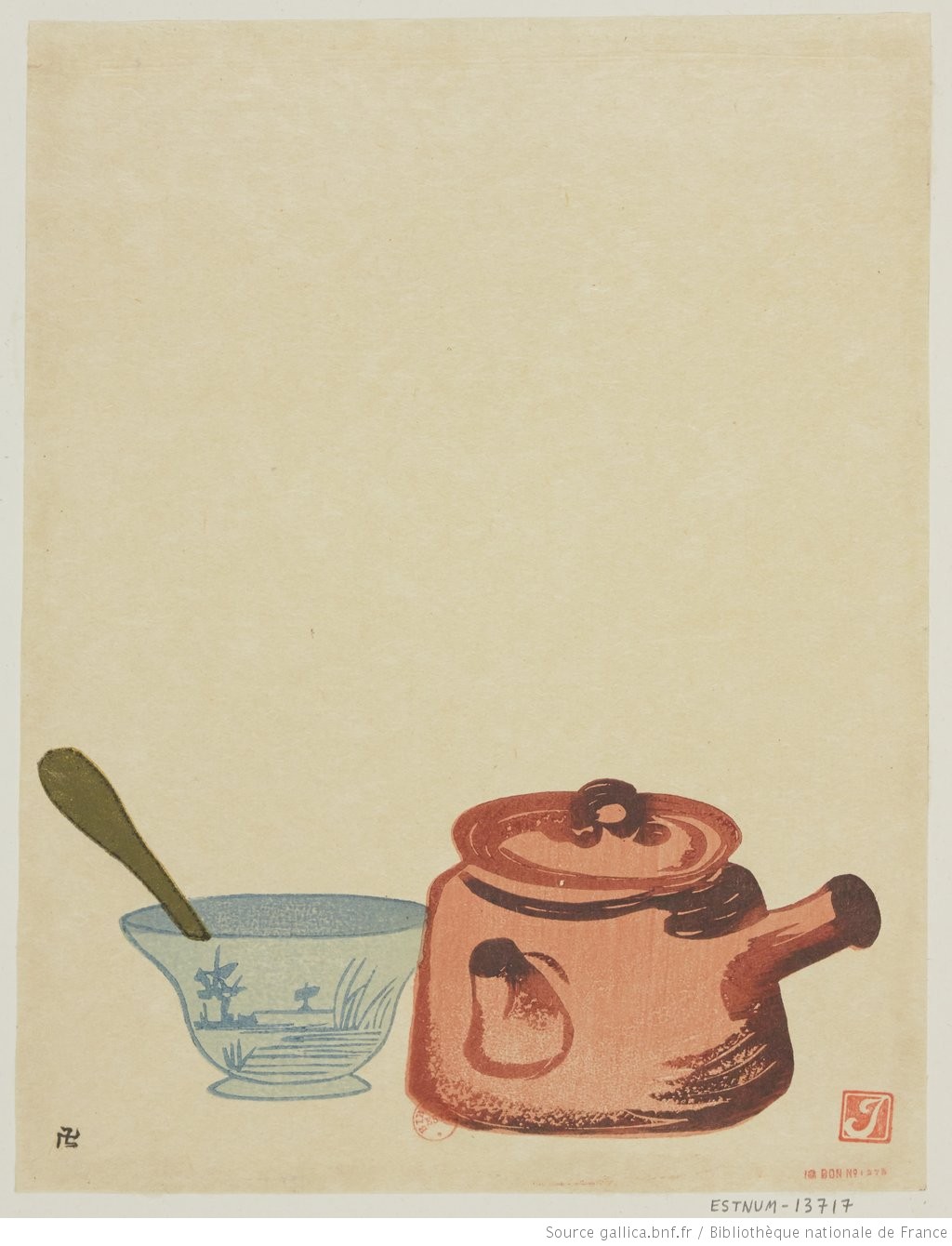

Isaac truly integrated into the Japanese culture of the capital in the early 1890s, upon the foundation of the Society of Friends of Japanese Art (la Société des amis de l’art japonais) by Siegfried Bing (1838-1905). He participated in the society's first monthly meeting on March 12, 1892, and did not miss a single one until 1910 – Henri Vever (1854-1942) hadresumed meetings in 1906 shortly after Bing's death. Alongside about fifteen other Japanese engravers, Isaac was the designer of several invitation cards between 1906 and 1914 – eight original prints and five prints after Japanese works by Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重) [1797-] 1858], Kitao Masayoshi (北尾政)[1764-1824], and Ogata Kôrin (尾形光琳) [1658-1716] – and the printer of about fifteen cartoons. Isaac's original prints, of a varied nature, represent compositions of plants, animals or even Japanese objects.

With the members of the Society of Friends of Japanese Art, Isaac participated in the founding of the Franco-Japanese Society of Paris (la Société franco-japonaise de Paris) after the Universal Exhibition of 1900 and was elected a life member. He created two menus for this new company as well as the certificate issued to all members. Intentionally combining French and Japanese symbols, the certificate portrayed a rooster crowing in a field of cornflowers and poppies, overlooked by Mount Fuji and a rising sun (Grand Diplôme de la Société franco-japanaise de Paris, wood engraving in the Japanese style, undated, Paris, BnF).

Dyed Fabrics

After starting out as a painter, Isaac steered his career towards decoration, particularly textiles. His taste for Japanese art led him to an interest in the processes of dyeing fabric, which he engaged in from the mid-1890s in his own workshop. He apparently acquired the technique empirically after a certain number of trials. He used both stencil printing inspired by Japanese katagami and another process that he invented, consisting of "engraving" motifs directly into the fabric.

Encouraged by Siegfried Bing, he launched the production of fabrics, hangings, curtains, screens, armchairs, tablecloths, bedspreads, fans, handbags, which were exhibited between 1895 and 1897 in the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts and in the Salon de la Rose-Croix in Paris, in Liège and in Dresden. He was also part of Bing's Art Nouveau gallery from its inauguration in 1895 where in the he exhibited three panels for bench backs (no 521) and eight frames of stained wood fabric panels (no 522) in the "Furniture" section. In the "Fabrics and Hangings" section, he exhibited a hanging of a rotunda salon in eleven panels and a frieze (no 541) [Salon de l'Art nouveau, 1896].

Japanese-Style Engraving

Shortly after Bing's death, Isaac decided to abandon textile decoration to fully devote himself to engraving. His earliest known attempts date back to 1900 when he dabbled in drypoint and aquatint and mostly depicted Dutch and Venetian landscapes. His transition to printmaking in the Japanese style began a few years later, particularly with his attempts at coloured engravings on alabaster where he accentuated the black contour line and treated the colours in large flat areas according to the ukiyo-e model. These turn-of-the-century prints show Isaac’s first use of a monogram in red or black Indian ink in two different forms: a “flowery I” and/or his full name. His monogram was accompanied by a swastika affixed in black, which he systematically added (Gondoles à Venise, engraving on alabaster, undated, Paris, BnF).

From 1905, Isaac tried his hand at coloured wood engraving, which would become his preferred medium until his death in 1924. His first attempts were hesitant: he began by making black and white prints, which he then coloured one by one with a brush (see Composition, jouets et pavots dans un vase, 1906, Paris, BnF). In 1908, during the Anglo-Japanese exhibition in London, he met Urushibara Yoshijirô (漆原木虫) [1889-1953], a young nineteen-year-old artist. Working for the famous Shimbi Shoin printing press in Tokyo, he had been hired as a "demonstrator" of the Japanese woodcut technique. Enthusiastic about this meeting, Isaac offered to join him and to accompany him to Paris to provide personal instruction regarding his own know-how. Together, they produced a certain number of four-handed engravings, which they signed with their two monograms (Urushibara Yoshijrô and Prosper-Alphonse Isaac, Outils de graveur sur cuivre, wood engraving in the Japanese style, 1908-1912, Paris, BnF).

At the same time, Isaac collaborated with other Japanese engravers, including Noguchi Shunbi (駿尾 野口) [?-1946] (Noguchi Shunbi and Prosper-Alphonse Isaac, Canard, woodcut in the Japanese style, 1908-1912, Paris , BnF).

Through practice, Isaac soon reached a technical level that earned him the reputation of a specialist in wood engraving in the Japanese style. He in turn trained several engravers and designers – including Jules Chadel (1870-1941) and Géo-Fourrier (Georges Fourrier, 1898-1966) – and in May 1913 published the first treatise on the subject in the journal Art et Décoration. As a professional printer, he procured woodcuts by Japanese artists, made reprints of them

and bequeathed around a hundred to the Prints Department of the Bibliothèque nationale. His engraved work, which includes just under 200 prints, is kept in the département des Estampes of the Bibliothèque nationale de France and at the Bibliothèque d'histoire de l’art et d’archéologie (De Belleville A., 2000, p. 187).

The Collection

Prosper-Alphonse Isaac probably began his collection of Japanese art during the 1880s, diligently frequenting the shops of Siegfried Bing and Hayashi Tadamasa (林忠正) [1853-1906], and probably the Hôtel Drouot, where sales by collectors of the first generation were held successively between 1890 and 1914. In a few years, he thus built an important collection of more than a thousand objects: fabrics, dolls, bronzes, paintings, and above all illustrated books and ukiyo-e prints of all periods and all styles (Vabre E., 2009-2010, p. 32-33). Between 1909 and 1914, Isaac lent part of his collection each year for the major exhibitions of Japanese prints held at the Marsan pavilion (Vabre E., 2011-2021, p. 6).

As an active donor, he enriched the collections of the musée du Louvre, the musée des Arts décoratifs, and the Bibliothèque nationale. It was Gaston Migeon, curator of the Louvre's Works of Art department and member of the Society of Friends of Japanese Art, who first encouraged Isaac to part with a few objects from his collection, with the aim of offering institutional recognition for Japanese art. Isaac gave the Louvre a carved wooden Japanese mask in May 1897 and a “triptych sheet” in 1912.

He also took part in “group gifts,” considering the volume of his collection. For example, he offered four prints on March 5, 1894, alongside Henri Vever, Siegfried Bing, Raymond Koechlin (1860-1931), and Charles Gillot (1853-1904).

When Isaac died in 1924, the Louvre's Asian collection was enriched a last time when his brother, Louis Isaac, donated three Japanese paintings. The musée des Arts décoratifs, then directed by Louis Metman (1862-1943), received a piece of Japanese silk fabric and a batch of fusumagami (paper used to decorate screens) in 1912. For the same institution, Isaac complemented the albums of Jules Maciet (1846-1911) by sending prints, invitations, and menus. Between 1909 and 1922, Isaac sent a batch of 96 prints that he had made himself from Japanese dyes to the Bibliothèque nationale. This curious set reveals another facet of his collection: passionate about engraving processes, the painter had been able to collect around a hundred woodcuts despite their rarity (Japanese legislation requiring their destruction after a certain number of prints). Their current location remains unknown since they do not appear in the inventories of donations or in his sales catalogue. We know that he regularly lent these matrices to his engraver friends, and it is possible that some were given to them (Vabre E., 2009-2010, p. 38-42).

Alongside his efforts to further the dissemination of Japanese art, several donations reveal Isaac's interest in the arts of Islam, which he collected more modestly: in 1894 he offered the Louvre a tile of coating and a flat Persian glass bottle (16th or 17th century), and in 1924 a 17th century Iranian miniature titled Jeune Homme tenant un livre ouver (Laclotte M., 1989, p. 235). Isaac was undoubtedly initiated by Gaston Migeon in the 1890s at a time when many Japanese scholars were interested in Muslim art, notably Raymond Koechlin, Henri Vever, and Georges Marteau (1858-1916).

From the 1910s, Isaac's collection took a turn towards Chinese art while Japonisme faded and a new generation of specialised dealers emerged. Once again, the donations tell us about the nature of this collection: in 1912, the painter gave the Louvre a Chinese painting dated from the 17th century; on December 9, 1913, the musée des Arts décoratifs received two small pieces of 19th-century Chinese furniture, a stool and a child's armchair. After his death, the Isaac family donated ancient bronzes twice to the museum, including a bowl that would illustrate the book L'Art chinois (1925) by Gaston Migeon (Vabre E., 2009-2010, p. 32-41).

Today, Isaac's Japanese collection is dispersed between donations to museums and libraries, and the auction organised by his family a year and a half after his death from December 21 to 23, 1925. This sale included 668 lots, more than a thousand objects, mainly prints, illustrated books, dolls, and textiles, as well as a few drawings, fans and bronzes. There are also some Chinese objects (drawings and bronzes) and Indo-Persian miniatures from the 17th century. Within the prints that date from the 17th century to the first half of the 19th century, the principal masters are depicted: the primitive Hishikawa Moronobu (菱川 師宣) [1618-1694], his pupil Hishikawa Morofusa (師房 菱川) [active 1685- 1703] and Torii Kiyonobu (鳥居 清信) [1664-1769], around thirty prints by Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信) [1725-1770] and as many by Isoda Koryusai (礒田湖龍斎) [1735-1790), 80 prints by Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿) [1753-1806], 13 of Hokusai's 36 Views of Mount Fuji (葛飾 北斎) [1760-1849] and nearly a hundred works by Hiroshige including 19 of the 53 Stations of the Tokaido. The subjects were varied, with no obvious preference: portraits of actors (yakusha-e), beautiful women (bijin-ga), landscapes (meisho-e). Erotic prints (shunga), however, which were then in vogue, are absent. Isaac was also a great collector of illustrated books (ehon): Hokusai and his Manga, Kawamura Bumpo (河村 文鳳) [1779-1821], Yamaguchi Soken (山口 素絢) [1759-1818], and especially Kitao Masayoshi (北尾政美) [1764-1824], pupil of Hokusai, of whose books he owned about ten volumes (Vabre E., 2009-2010, p. 34-36).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne