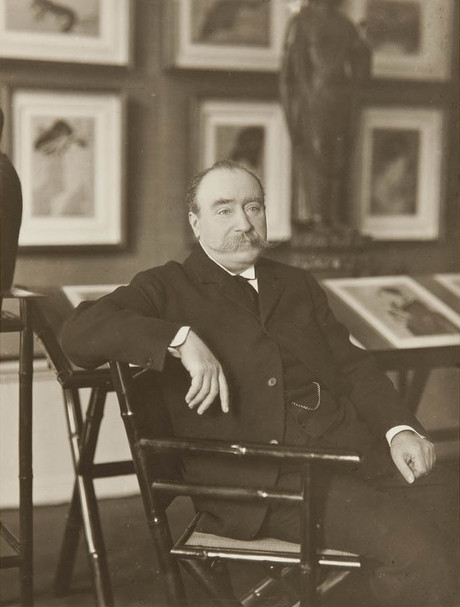

CAMONDO Isaac de (EN)

Biographical Article

Count Isaac de Camondo was born in Constantinople in 1851 and came from a line of Sephardic Jewish financiers who built their fortune in Turkey. His family moved to Paris when he was 18 years old. Quickly associated with the family business, he assisted his father and his uncle and then succeeded them in the management and administration of their banking house and numerous companies. From 1891 to 1895, he built upon the close ties between the Ottoman power and his family by assuming the functions of Consul General of Turkey.

The Musician-Composer

Subsequently, he gradually turned away from his official obligations and financial activities to give free rein to his artistic temperament. As a musician from an early age and a fervent Wagnerian, he wrote several melodies, and, in 1906, an opera Le Clown which was performed in public, thanks particularly to his lifelong friend Gabriel Astruc (1864-1938). This publisher, concert organiser, and artistic agent was a key figure in the Parisian musical world. Isaac de Camondo supported him financially on many occasions and helped him to realise his finest project: the creation of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, on avenue Montaigne in Paris.

The Collector

Above all, he became famous as a collector Eclectic in his tastes, he was seduced in turn by the art of the Far East, the decorative arts of the French 18th century, and then Impressionism. He received advice from his museum curator friends and also assembled sculptures from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance as well as ceramics from the 17th and 18th centuries. It was in 1881, during the sale of the collection of Baron Double, an 18th century art lover, that Isaac de Camondo became a recognized and admired collector. At these auctions, he not only acquired the clock known as Aux Trois Grâces – the star object of its sale – but also furniture and objects and tapestries from the French 18th century. His interest in art seems to have manifested itself as soon as he moved to Paris. Residing in a wing of the family mansion at 61 rue de Monceau, he accompanied his father and uncle to galleries, antique dealers, and auction houses as they furnished their homes. Like them, he became a Japoniste and started to purchase of works of art from the Far East, his first passion. Isaac de Camondo moved several times. In his last apartment, located at 82 avenue des Champs-Élysées, two galleries were devoted to the exhibition of works of art from the Far East. Often advised by the publisher, printer, and art dealer Michel Manzi (1849-1915), he enriched his collection throughout his life. His collection was of exceptional quality and was composed primarily of Thai sculptural pieces, Chinese art works including a monumental bronze ritual vase in the shape of an elephant, known as Zun Camondo, and Japanese art works - sculptures, masks, ceramics, bronzes, and lacquers — as well as more than four hundred prints. This highly coherent set brought together quality proofs by many masters, such as Hiroshige (1797-1858), Utamaro (1753-1806), Toshinobu, Sharaku, and Hokusai (1760-1849).

Impressionism

During the last decade of the 19th century, Isaac de Camondo discovered Impressionism. He followed his instincts and heeded the advice of the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), a tireless defender of these much-maligned artists. The painters Johann-Bartold Jongkind (1819-1891) and Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) first gained his favour. He then became enthusiastic about the talent of Edgar Degas (1834-1917), with whom he paradoxically had little contact, but from whom he acquired twenty-five works, including: La Classe de danse, L'Absinthe, Chevaux de courses devant les tribunes, and Le Tub. He exhibited these masterpieces in the living room by the piano where they inspired him, as he aspired to create a musical equivalent to Impressionist painting. Alongside his musical activities, he continued to make acquisitions. Among the masterpieces he chose were Le Fifre et Lola de Valence by Édouard Manet (1832-1883), L’inondation à Port-Marly, La Barque pendant l’inondation, and La Neige à Louveciennes by Alfred Sisley (1839-1899). During one of his visits to Giverny to see Claude Monet (1840-1926), with whom he became friends, he bought four canvases from the Cathedrals series. He also chose Le Parlement de Londres and Le Bassin d’Argenteuil. At the same time, he became interested in Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), from whom he acquired several watercolours in 1895 at the Vollard gallery. At the turn of the century, he bought La Maison du pendu, then, shortly before his death, Les Joueurs de cartes. Later, he became seduced by the talent of Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901).

The Donor

Isaac de Camondo, who never married, never concealed his wish to bequeath his collections to the Musée du Louvre. Indeed, several curators had close relationships with him and influenced his tastes and his purchases. He was also one of the founders of the Société des Amis du Louvre where he served as vice-president. Upon his death in 1911, he bequeathed his collections to the Louvre, on the condition that the whole be exhibited together for fifty years in a series of rooms bearing his name. The collection thus presented was inaugurated in 1920. Around a hundred Impressionist paintings, pastels and drawings thus made their sensational and contested entry into the Louvre. Indeed, the regulations prohibited the presentation of works by artists living or recently dead. Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), then an art critic, noted with delight that this venerable institution had become the true modern museum of Paris. After the Second World War, the designated fifty years having almost passed, the works bequeathed by Isaac de Camondo were distributed among various departments of the museum. One room in the département des Objets d’art still bears his name today. The Asian collections joined the Musée Guimet and the Impressionists went to the Musée du Jeu de Paume, then to the Musée d'Orsay. The Palace of Versailles and the Musée Maritime have also benefited from works from the legacy of Isaac de Camondo, whose exacting choices captured the best of his time’s cultural life and generously offered it to posterity.

The Collection

Isaac de Camondo may have developed his taste for Asian art under the influence of his father, Abraham Behor de Camondo (1829-1889), who frequented art dealers of the Far East and collected works of Asian art. Isaac de Camondo was thus able to accompany his father to "La Porte Chinoise" or to Auguste and Philippe Sichel. The Journal des frères Goncourt testifies to the presence of the Camondos (unfortunately without specifying their first names) at Auguste Sichel's (1838-1886), dining "in front of a soup with swallows' nests" in the company of Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896), dated Thursday, June 17, 1875 (Goncourt J. and E., 1989, p. 651). It should be noted that Isaac de Camondo only went to Sichel when he was just starting out as a collector, between 1874 and 1877. Gaston Migeon (1861-1930) indicates that Isaac de Camondo wanted to go to Japan at this time (Migeon G. , 1913, p. 5); however, the trip never took place. Isaac de Camondo also quickly became a member of the group of Japanese art lovers who met in the gallery of Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) and was part of the Amis de l’Art Japonais association, which met monthly at the restaurant Cardinal.

Isaac de Camondo’s purchase of Far Eastern works can be grouped into three main phases: the first, from 1874 to 1877, corresponds to his first purchases as a collector. In 1874, Isaac de Camondo purchased from Auguste Sichel Korean armour, five gold and silver sconces depicting gods, a Japanese sword, a bronze vase, and an incense burner. In 1877, he again acquired eight Asian art objects. In four years, he had therefore acquired nineteen Far Eastern works of art, i.e. he donated a quarter of the total number of Asian works of art to the Louvre (80). After these first purchases, Isaac de Camondo spent no further money on Asian works of art until 1899. On the other hand, he bought Japanese prints in 1894, from the dealer Michel Manzi (1849-1915), who sold him "in a few months, between 1894 and 1895, a splendid collection of Japanese prints" (Migeon G., 1913, p. 6).

After the prints, Isaac de Camondo went back to buying Asian works of art, from 1899 until his death in April 1911. After inheriting his father's fortune in 1893, his financial means increased considerably. He therefore acquired about sixty art objects in thirteen years, that is to say the last three quarters of his collection of Asian art objects. He also completed his collection of prints by buying thirteen in 1902, four in 1903 and two in 1906, bringing the number of his prints to four hundred and twenty. Finally he bought some paintings.

Purchases of works of art from the Far East are thus found at the two extremes of Isaac de Camondo's life as a collector: the first and last years. His biggest purchase, that of the four hundred prints, took place in 1894, i.e. just when he entered into the enjoyment of his father’s fortune. The dealers Auguste Sichel, from 1874, and Siegfried Bing, from 1877, sold him the greatest number of Asian works of art: he thus bought a total of twenty-one works from Auguste Sichel and thirty from Siegfried Bing. Michel Manzi also played an important role by selling him a batch of Japanese prints in 1894, but their relations continued only a short time. In total, Far Eastern art corresponds to 61% of the works in Isaac de Camondo's collection at his death, this high percentage being explained by the large number of Japanese prints.

Isaac de Camondo also occasionally lent works to the Salon d'Automne (three Japanese prints, in 1905) (MNC, correspondance d’Isaac de Camondo “Art- 1904-1905”, Lettre de Paul-Louis Garnier à Isaac de Camondo, 9 octobre 1905) or to exhibitions abroad. Thus, he sent a Chinese bronze "encrusted with intertwined fish" to an exhibition in Saint Petersburg (MNC, correspondance d’Isaac de Camondo “Art-1892-1903”, Lettre à Isaac de Camondo, février 1904). Michel Manzi asked Isaac de Camondo for the loan of Japanese prints for an exhibition at the Hôtel des Modes (MNC, Correspondance Isaac de Camondo, dossier Manzi et Joyant, lettre du 25 mai, [year unreadable], entre 1907 et 1911). The collector was also one of the lenders of the exhibition of Japanese prints organised in February 1909 at the musée des Arts décoratifs (Estampes japonaises primitives, musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, 1909).

In early December 1907, Isaac de Camondo moved to the third floor of a building located at 82 Avenue des Champs-Élysées. Of the ten rooms in the apartment, six were fitted out exclusively for the display of the collection, including a "gallery" of Far Eastern art (according to the terms of the post-mortem inventory of April 20, 1911, study by Mr. Andre Charpentier). In his previous apartment in rue Gluck, Isaac de Camondo had already set up a specific room for the presentation of his Japanese prints. On the avenue des Champs-Élysées, a Far Eastern art gallery adjoining the large living room was furnished with Asian furniture. The walls were covered with framed prints and the works of art were placed on bamboo pedestals (fifteen pedestals in total), evenly spaced from each other and aligned in the centre of the gallery. This gallery can be seen in the upper left part of a painting by Henri Lebasque, dated 1910, representing one of the (born out of wedlock) sons of Isaac de Camondo standing in the living room (Portrait of Jean Bertrand in the apartment of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, 1910, H. 73; L. 92 cm, oil on canvas, private collection).

The Asian art collection of Isaac de Camondo seems to have been developed largely with the intention of a donation to the Musée du Louvre, in consultation with Gaston Migeon, curator in the département des Objets d’art at the Louvre and himself a collector of Asian art. A letter from Albert Kaempfen (1826-1907), former director of the Musées nationaux, to the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts indicates that in 1907 "almost the entire collection of sculptures and objects from the China and Japan was acquired by mutual agreement with Mr. Gaston Migeon” (AN, Z/8/1912). For example, Gaston Migeon received a small marble tombstone from China in November 1909 and addressed the following words to Isaac de Camondo: “I would like to see this small sculpture enter your collections if you like it. The asking price is 850 francs, but I think I can get it lowered” (MNC, dossier Gaston Migeon, correspondance d’Isaac de Camondo “Art-personnalités”, Lettre de Gaston Migeon à Isaac de Camondo, 16 novembre 1909). Moreover, Migeon seems to have regularly sent Asian art lovers to Isaac de Camondo to admire his collection (see for example in 1904, visit of the Japanologist Ernest Fenellosa, MNC, dossier Gaston Migeon, correspondance d’Isaac de Camondo “Art-personnalités”, Lettre de Gaston Migeon à Isaac de Camondo [undated]).

Isaac de Camondo made three successive donations subject to usufruct to the Louvre Museum, after expressing his desire in 1895 (AN, F/21/4442 and F/21/4459). The first donation, dated March 31, 1897 (acceptance decree of June 20, 1901) mainly contained Japanese prints (eighteen) and works of art from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (six). The second donation, made on July 27, 1903 (decree of December 26, 1903), included thirteen objects: ten works of art from the Far East, a Japanese print (by Hokusai), and two works of art from the Middle Age. Finally, the third donation, dated November 8, 1906 (decree of November 30, 1907), included thirteen works, all from the Far East. Nine of them came from the 1904 Gillot sale and there were eleven works of art and two prints.

Donations subject to usufruct by Isaac de Camondo totally excluded 18th century and modern art. The most personal part of his collection therefore had to be bequeathed. Isaac de Camondo had drawn up his will on December 18, 1908, in which he wrote: "I bequeath the entire collection to the Louvre Museum with one hundred thousand francs for installation expenses. The Louvre must receive the entirety and exhibit it. The Louvre must put my collection in a special room bearing my name for fifty years” (Will of Isaac de Camondo, December 18, 1908, study by Me. Charpentier). The bequest included, in addition to works from the Far East and works from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, modern paintings and drawings and works of art from the 18th century. Isaac de Camondo died on April 7, 1911; the decree of acceptance of the donation dates from November 23, 1911 (amendment decree December 17, 1912). A total of seven hundred and forty-eight works were bequeathed to the Louvre Museum, in addition to works that had already been donated. The Asian art collection of Isaac de Camondo is now kept at the Musée Guimet.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne