GUÉRARD Henri (EN)

Biographical Article

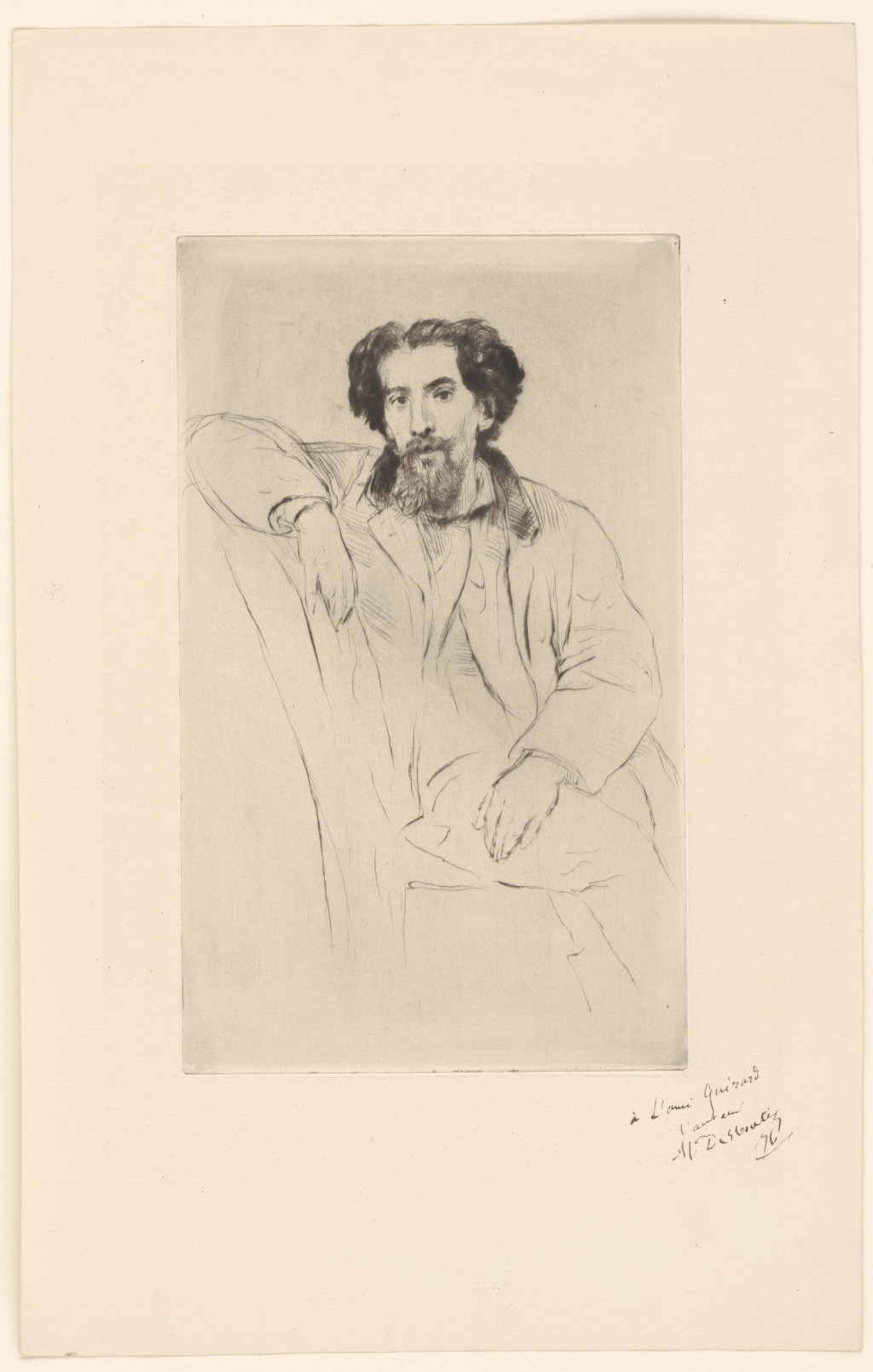

Henri Guérard, son of Charles Étienne Guérard and Marie Justine Augustine Ruel de Forge, was born on April 26, 1846 at 41 rue Bourbon Villeneuve in Paris (AP, 5Mi1 595) and died on March 24, 1897 at his home at 4 avenue Frochot (AP, V4E 8841). Apainter, engraver, draftsman, illustrator, modeller, decorator and collector, the artist was particularly renowned in his time for his reproduction engravings, his commitment to the recognition of the original engraving, and his artistic experiments such as pyrography. In addition, he developed a passion for Japanese art and, more broadly, for the culture of the Far East.

Artistic Beginnings and First Contacts with Japoniste Circles

Henri Guérard officially began his artistic career in 1870. At the age of 24, he presented a painting entitled Le Puits (Salon des artistes français, 1870, p. 165) at the Salon. The catalogue mentions that he was a pupil of the painter-engraver Nicolas Berthon (1831-1888). The artist produced one of his first etchings in 1867 and devoted himself more to engraving from 1872. Between 1874 and 1876, he collaborated with the magazine Paris à l'eau forte, which played an important role in the revival of original engraving in France. It was in this context that he first came into contact with a number of japoniste artists such as Henry Somm (1844-1907), Frédéric Régamey (1849-1925), Dufour, and Félix Buhot (1847-1898).

He was also close to Édouard Manet (1832-1883), for whom he printed engravings between 1874 and 1882, and in 1879 married Eva Gonzalès (1849-1883), a famous pupil of the painter of the Olympia. She died a few days after giving birth and her teacher’s death, leaving a tiny son who was to be cared for by her sister, Jeanne Gonzalès (1852-1924). Guérard married the latter in 1888, five years after the death of his first wife.

It was also likely in the second half of the 1870s that Guérard met one of the first Japonistes scholars and collectors of the art of the Far East, Philippe Burty (1830-1890), with whom he maintained a deep friendship. The correspondence preserved in the department of prints and photography of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Dossier Henri Guérard. Z-80 [5-6]) testifies to their common passion and reveals the great sense of complicity between the two men; Burty signed a letter written on a Tuesday in November 1888: "Votre frère en Japonisme, Ph. Burty-sama" (BNF, Archives Bailly-Herzberg, Henri Guérard, Z-80 [5]). Burty wrote on delicate paper with letters decorated with Japanese figures and regularly asked Guérard to print engravings, which he executed from objects in his collection.

Career as Illustrator; Special Access to Asian Art Collections

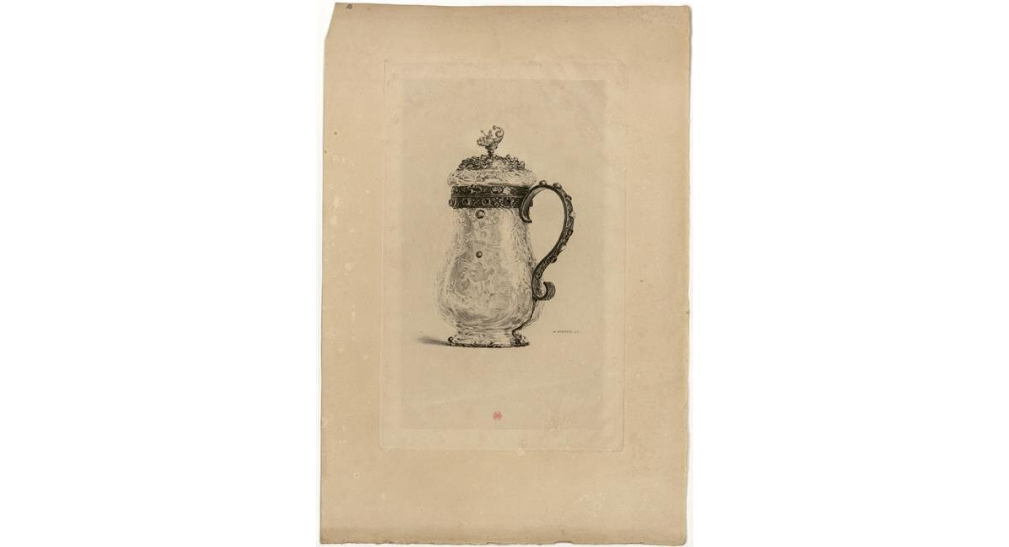

Parallel to his activity as an engraver in 1875, Guérard launched a career as an illustrator and more specifically as an engraver-interpreter, starting in 1876. For nearly seventeen years, from 1880 to 1897, the artist collaborated with La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, which gave him the opportunity to participate in several major projects in the history of Japonisme. His work was noticed by Louis Gonse (1846-1921), the magazine’s editor-in-chief, who in 1882 asked him to illustrate L’Art japonais, published in 1883 (BNF, Archives Guérard, YB3-4158-4). He then produced eleven etchings and more than two hundred drawings from the collections of Louis Gonse, Philippe Burty, Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896), Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), Antonin Proust (1832-1905), Auguste Dreyfus (1827-1897), Alphonse Hirsch (1843-1884), Edmond Taigny (1828-1906), José-Maria de Hérédia (1842-1905), Antoine de la Narde, Georges Petit (1856-1920), and Wakai Kenzaburō (1834-1908), vice-president of the Japanese section of the Exposition Universelle of 1878. Guérard also made some illustrations for Le Catalogue de l’Exposition rétrospective de l’art japonais, an exhibition organised by Gonse a few months before the publication of L’Art japonais. Between 1888 and 1890, he also collaborated with the art dealer and collector Siegfried Bing on the magazine Le Japon artistique by creating sixteen signed and unsigned plates from the text (Quoix A., 2016, p. 39-40).

The artist did not only illustrate works devoted to Japanese art. He contributed 100 drawings to L’Art chinois of Maurice Paléologue (1859-1844), published in 1887. One depicts a bronze sculpture from his own collection representing the god Kui Xìng (Paléologue M., 1887, p. 64).

Thus through his various collaborations Guérard became an essential player in the history of Japonisme and contributed in a global way to the dissemination of Asian art in Europe. This also gave him the opportunity to closely observe the objects present in the greatest Asian art collections of the time and represented an undeniable source of knowledge for the artist.

Following the publication of L’Art japonais, Guérard acquired a great reputation in the field of interpretive engraving and was then presented by his contemporaries as the successor of Jules Jacquemart (1837-1880). The artist led the dual career of original engraver and reproduction engraver until 1889. He eventually abandoned the second activity.

Original Work

From January 1889, Henri Guérard increasingly devoted himself to gaining the recognition of engraving as an artistic expression in its own right and along with Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914) founded the Société des Peintres-Graveurs which worked for the revival of the original engraving in France. At this time, it was less a society strictly speaking than a loosely based group of artists. The society was formalised in December 1890 under the official name of Société des Peintres-Graveurs français, and Guérard served as its vice-president until his death in 1897.

An eclectic artist with many facets, Guérard was interested in more than just engraving. His abundant production of works of art also includes oil paintings, watercolours, pyrography, lithographs, and sculptures, as well as creations from the decorative arts such as screens, panels to go above doors, vases, plates, goblets, gourds, and even pewter escutcheons for furniture.

While these different works reveal Guérard's attraction to Japanese art, his passion for the art and culture of the Land of the Rising Sun is most strikingly manifested through his set of fan-shaped paintings. In this area, Guérard was one of the most productive artists, designing more than 300 throughout his career (Quoix A., 2021, p. 150). He presented them at each of his personal exhibitions, from the first one at the gallery of the magazine La Vie moderne in 1879 to the last at La Bodinière in 1896.

In a posthumous tribute, the art critic and friend of Guérard Roger Marx (1859-1913) recalls about the artist that "Nippon [was] his school in Rome" and that as a "Japanese from Paris, he [has] continued his task, like the old masters of the Rising Sun” (Marx R., 1897, p. 315 and 318).

The Collection

The sources discovered to date do not allow us to know with precision which objects were present in Henri Guérard's collection. The posthumous inventory is a valuable source, offering an overview of the types of object he collected (AN, MC/ET/XLI/1341). Additionally, scattered sources such as photographs, drawings, and engravings allow the visualisation of some of the objects in his collection. Finally, a sales catalogue from 1975 (BNF, Archives Bailly-Herzberg, Henri Guérard, Z-80 [5]) as well as the pages of a notebook that belonged to the art historian Janine Bailly-Herzberg give us a glimpse of the Japanese artists who may have been represented in Henri Guérard's collection. These latter sources are, however, less reliable given that Guérard's son added to his father's collection after the latter's death (Quoix A., 2017, pp. 24-27).

According to the inventory of Henri Guérard's possessions, drawn up at his home at 4 avenue Frochot in Paris about a week after his death (AN, MC/ET/XLI/1341), the artist possessed the following: 200 showcase objects, including porcelains, oriental objects, bronzes, netsuke, ivories and stoneware; a hundred pieces of porcelain and stoneware from China and Japan; thirteen masks, nine of which are specified to be Japanese and two of burnt wood; five Japanese albums and another batch of Japanese albums; seven Japanese swords; four ceramic vases; and two Chinese teapots. Guérard also had a Japanese bronze vase, a Japanese bronze incense burner, a Japanese porcelain water jug, a hexagonal Chinese porcelain vase, an incomplete Japanese armour, and a Japanese-style watercolour, as well as a Japanese screen and a bamboo screen.

Sources from the 1970s cited above mention tsuba, netsuke and small masks, a Japanese tray, snuffboxes, a screen, a "god of longevity on a doe, in bronze", masks of nō and sculptures of animals such as crabs, a turtle, lobsters, a rooster, a snake, a grasshopper, and a spider.

Japanese and Chinese albums are also noted, including books of studies of flowers, birds, and other animals; a book containing fourteen actor portraits by Katsukawa Shunshō (1726-1792); a book inspired by kabuki scenes by Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), sixteen copies of Hokusai's Manga (1760-1849) and nine study books by the same artist.

In addition to these Far Eastern objects, Guérard also owned paintings, drawings and engravings by European artists – including at least one drawing by Rembrandt (1606-1669), as well as bronze sculptures and figurines – the posthumous inventory mentions in particular an elephant in bronze by Antoine-Louis Barye (1795-1875). The painter-engraver also had a collection of pewter castings, including medallions and a collection of 120 lanterns from different periods that he began to collect around 1873. This collection is mentioned by Richard Lesclide (1825- 1892), editor of the journal Paris à l’eau-forte in an article of October 1874 (Lesclide R., 1874, p. 155-157). Guérard made drawings and engravings of his lanterns, which he associated with a poem. He engraved some from 1873 to 1890. In 1976, Claudie Bertin devoted an article to this collection of lanterns.

Henri Guérard's collection is characterised by a sort of heterogeneity that probably reflects this painter-engraver’s personality and is found in his artistic practice and his production of works of art. It is also likely that his collection was preserved as it was long after his death, the artist having specified in his will: "I wish as far as possible that no sale be made of movable or immovable objects, which will be part of my estate, being convinced that my paintings, engravings and works of art decorating my workshop and house will only increase in value […] which will later increase my son's assets” (AN, MC/ET/XLI/1341). His collection of lanterns was dispersed in 1968, according to Claudie Bertin(Bertin C., 1976, p. 171).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne