HATTY madame (EN)

Biographical Article

An obituary published in the pages of the Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot in 1908 praised "the brilliant little" Madame Hatty, "a woman with a highly developed artistic sense" who "specialised in Japanese works of art, a branch of curiosity that 'she had done much to make fashionable with the late M. Bing [Siegfried Bing, 1838-1905]' (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, February 26, 28, 1908, p. 2). Another tribute, published in Le Journal des arts, insists on "her knowledge and her personal good grace", while emphasising her "important antique store", specialised "in the trade of works of art from China and Japan” (Le Journal des arts, February 26, 1908, p. 3). Forgotten today, Madame Hatty was, as these two publications note, one of the major figures who helped popularise the arts of Japan at the end of the 19th century: she was among the most active bidders at the public auctions of Asian objects in 1883 and 1893 (Saint-Raymond L., 2021, p. 445, 447), she exhibited her own collection (Exposition universelle of 1889), and sold to major collectors of her time such as Émile Guimet (1836-1918), Clémence d'Ennery (1823-1898) or Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912). While we now have little evidence of her personality and motivations, the details contained in these obituaries allow us to reconstruct something of the identity of the woman so long hidden behind the pseudonym "Madame Hatty".

Referring to Madame Hatty's "highly developed artistic sense", the Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot noted that she was the niece of the painter Victor Dupré (1816-1879) (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, February 26, 28, 1908, p.2), a relationship which as of now remains unconfirmed, but not impossible (her father would thus be the illegitimate son of the porcelain manufacturer François Dupré (1780-1837), whose family lived in Paris in 1818, the year Charles Louis Dupré was born, on March 24, to an "unnamed" father (AP 5Mi1/198/2378). Madame Hatty was indeed called "Dupré": named Prudence Henriette (of which "Hatty" is the diminutive) Dupré in the civil register, was born in La Chapelle (Paris) on June 4, 1841 to Pierre Charles Dupré, laborer, and Henriette Mercier, florist (AP, 5Mi1/509/1942). On the date of her marriage with François Faivre (dates unknown) on August 30, 1859 (AP, V4E/10328/59), she was still living with her parents in Montmartre. She asked for a divorce on August 11, 1894, claiming the disappearance of Faivre; the divorce was declared by the Civil Court of the Seine on July 26, 1895 (AP, V4E/10328/59 and AP, 5Mi/2333/2455). The address indicated in this document (43 rue Laffitte) corresponds to that of Madame Hatty's store in 1895, thus definitively linking her pseudonym to her real name. In her time, no one, not even the auctioneers at the sale of part of her collection in 1895 (AP, D48E3 80, no 8037), ever seemed to link Madame Hatty publicly to Henriette Dupré.

Details related to the aesthetic training of "Madame Hatty" before the 1880s remain to be discovered, for it was not until the early 1880s that this name began to appear in the press, correspondence, and auctions (MNAAG, Correspondance, 1886; Saint-Raymond L, 2021, p. 445). Nor did the business appear in Bottin until 1887: "Hatty (Mme.), art objects, Châteaudun, 26" ("Bottin", p. 423). If Henriette Dupré truly was related to the painters Jules and Victor Dupré – who had practiced porcelain painting for their father, who manufactured porcelain – this would explain both her artistic and commercial networks and her knowledge of ceramics.

Her activities as a collector and dealer will be traced in the second part of this notice; meanwhile it is worth noting how her private and professional lives intersect, as was common at the time. Thus, the Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot describes "an artistic evening" which she organised to showcase her "magnificent salons on rue Laffitte" where "a large and chosen society" took part in a concert surrounded by "marvels of Japanese art" (paintings, prints, display cases "filled with ivory, jade and lacquerware of the highest worth" (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, July 23-24, 1892, p. 2). This was certainly an advertisement, intended to promote a new location (43, rue Laffitte), but this mixture of sociability and spectacle seems to confirm what the press reports of her "excellent heart" and her "somewhat whimsical character" (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, February 26, 28, 1908, p. 2).

Indeed, it is in terms of impulsiveness that the press presented her decision to "contract a marriage" with Abdallah ben Ali ben Hacène ben Kadj Kada Bendimerad (a man 27 years her junior) on December 13, 1900 in Tlemcen, Algeria. (AP, 5Mi1/509/1942; ANOM, Tlemcen, Algeria, December 13, 1900, act 71). According to an article ["Madame Hatty"], she closed the store after increasingly frequent business failures, a closure which must have been in 1899 (between the last advertisement published in the Gazette in July 1898 and her marriage in Algeria in 1900). Unfortunately, she seems to have regretted this marriage and departure abroad and ended her days in Algiers, alone, sick, and miserable, barely subsisting on a life annuity (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, February 26, 28, 1908, p. 2). Madame Hatty passed away on February 17, 1908 at the age of 67 (ANOM, Algiers, Algeria, February 17, 1908, act 465).

The Collection

Madame Hatty was both a merchant and a collector; like her contemporaries Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), Hayashi Tadamasa (林 忠正,1853-1906), and Florine Langweil (1861-1958), she kept a core set of objects – notably lacquerware, weapons, porcelain and prints – which she exhibited in the galleries of her store. In 1895, an article in the Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot described it as a "veritable collection": "For some twenty years she has been dealing in Japonisme, following all the sales, always in search of a rare and unknown bauble. Mrs. Hatty, her experience and knowledge coupled with her fine and delicate tastes, succeeded in assembling in her splendid salons a veritable collection of all manner of charming old knick-knacks, lacquers, porcelains, pottery, netzukes, etc. (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, April 9, 1895, p.3).

Such comments from 1895 suggests that Madame Hatty established her business in the late 1870s ("for twenty years"), consistent with her active participation in auctions in the early 1880s. In her study of asian objects acquired at Parisian auctions in 1883, for example, Léa Saint-Raymond places Madame Hatty in seventh place among the most assiduous buyers, preceded by dealers such as Antoine de la Narde (1839-?), Charles Mannheim (1833-1910) and Bing (Saint-Raymond L., 2016). Madame Hatty's business was first located on the rue des Martyrs; she also referred to it in 1886 when she invited Émile Guimet to come and discover her new store at 26, rue de Châteaudun: it contained objects "from China and Japan that I know you will like" (MNAAG, letter to Guimet from April 11, 1886). The latter accepted her invitation and she invoiced him for the objects he had chosen: three "stoneware figures" (45 francs), stoneware elephant (40 francs), "a fish-shaped sconce" (20 francs), a “piece of stoneware with 3 compartments” (15 francs) and “a craquelé cup with reflections” (25 francs) (MNAAG, letter from Madame Hatty to Guimet dated February 21, 1887). In June, he chose two more pieces for which she billed him 210 francs (she herself had paid 200 francs) (MNAAG, letter from Madame Hatty to Guimet dated June 21, 1887). In 1890, she offered him "a Japanese kakemono representing gods, which I believe you may like" (MNAAG, letter from Madame Hatty to Guimet of May 10, 1890).

To Clémence d'Ennery (1823-1898), who was fond of chimeras, Madame Hatty sold "a very small netsuke chimera in ivory with a white background decorated in red and black" (20 francs), "a small modern grey porcelain elephant" (10 francs) and "a little white animal lying down holding a ball in its paws in front of it.” D'Ennery indicates in her notebooks that she acquired these objects between 1894 and 1897 through the efforts of "Rose Bing" (probably Rose Bing Bloch, 1831-1897) (MNAAG, d'Ennery, 6e mille, sc, no 270, 271, 272). Lucie Chopard has inventoried the nineteen ceramics that Madame Hatty sold to Grandidier "before 1894, including 4 Japanese pieces, 2 porcelain from the Ming dynasty and 13 from the Qing dynasty" (Chopard L., 2021, vol. II, p. 154).

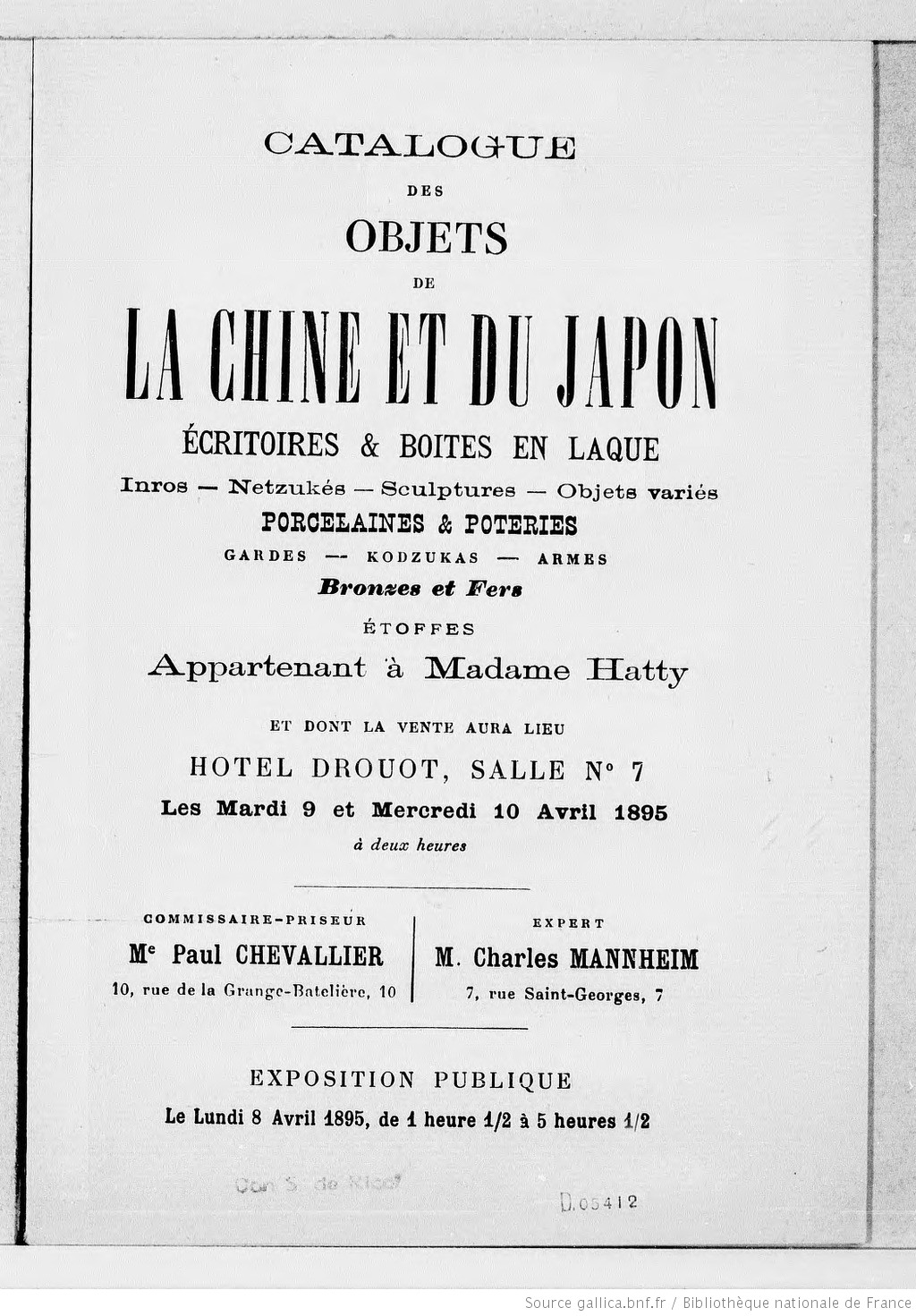

Madame Hatty's assiduous presence at auctions over a period of almost twenty years allows us to trace in detail her many acquisitions, the type and price of which are recorded in auction records. She notably participated in the major sales of her time, a provenance that she underlined in the detailed catalogue that she published before the sale of part of her collection at Drouot on April 9 and 10, 1895 (publicly exhibited on April 8, 1895). There were boxes, inkstands or inro in lacquer that had belonged to Philippe Burty (sale of 1891; lots 1, 2, 26-29), Auguste Sichel (sale of 1886; lot 3, 21, 22, 24), Alphonse Chanton (sale of 1862?; lot 5), L. Joly de Morey (sale of 1897; lot 23) and the "Daigremont and de Jouy sales" (lot 32; an object having passed through one of the sales of Joseph-Honoré-Désiré Daigremont [1790-1866], possibly through Henri Barbet de Jouy [1812-1896] and acquired at the latter's sale in 1879?). In terms of Chinese porcelain, she had selected bowls from the sales of Gustave Vapereau (sale of 1883; lot 86) and François-Philibert Marquis (sale of 1883; lot 94) sales as well as commercial objects ("Japanese pottery", netsuke and small objects sculpted in wood or ivory, weapons and saber guards (tsuba), Japanese bronzes and some fabrics). These references to the great collectors of her time show that Madame Hatty clearly understood advertising strategies: publishing a catalogue that cited the provenance of objects that had passed through the "majorsales" served to attract new buyers while affiliating their owner with a network of important collectors.

Madame Hatty had already demonstrated her understanding of the increased professionalisation of the trade: she participated in the 1889 Exposition universelle (section "Anthropology/Ethnography") by lending porcelain as well as curating two display cases in her name (vitrines 85 and 86): there were thirteen Japanese lacquer pieces (probably those acquired in the major sales of 1883 and 1886, cited above); twenty "Japanese wood and ivory groups" and "fourteen porcelain and earthenware sconces"; wooden tobacco pouches; and sabre hilts and knife handles (Exposition universelle, 1889).

Curiously, the 1895 sale did not include any Japanese prints, although according to the advertisements she published in the Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, this was one of her specialties (see, for example, the issues of 1896). She diligently acquired Japanese prints at auctions in the 1890s, some of which she exhibited in her shop before 1892 (Gazette de l’hôtel Drouot, July 23-24, 1892, p. 2). Prints do not take up much space, which suggests that she might have organised this public sale to get rid of the most cumbersome works (cabinets, bronzes, incense burners, fountains) with a view to fitting them into a smaller premises: she left the galleries at 43, rue Laffitte shortly after this sale, which took place the year of the official declaration of her divorce (1895).

An auction also had the advantage of generating money quickly and if she truly had financial difficulties, as the press suggested – "her business having failed her, completely discouraged after a long struggle" (Journal des Arts, February 25, 1908, p. 3) – this would explain both the sale and the move, for Madame Hatty, unlike contemporaries like Bing, Hayashi or Langweil, does not seem to have imported directly. Suddenly, she found herself in the situation of many other small businesses of the late 1890s who could not compete with the large traders who held a virtual monopoly on imports (Emery E., 2020, pp. 80-82). Those who won the highest priced items at her 1895 sale (up to 480 francs for lot 214, a Japanese fountain in gilded bronze) were, for the most part, other dealers: Antoine de la Narde, Laurent Héliot (1848-1909), and Florine Langweil (AP, D48E3 80).

The sale of 1895 seems to have given a few more years of life to Madame Hatty's business, which specialised more and more - as we have seen - in the sale of Japanese prints which had become popular after an important exhibition at the École des beaux-arts in 1890. We have not yet found a document showing the exact date of the liquidation of her business, but no more advertising for Madame Hatty's store is to be found after July 1898. We know that she left for Algeria with a life annuity, logically the fruit of her twenty years of commercial activity during which she participated in "making fashionable" the arts of Japan (Gazette de l'hôtel Drouot, February 26, 28, 1908, p. 2).

Related articles

Personne / collectivité