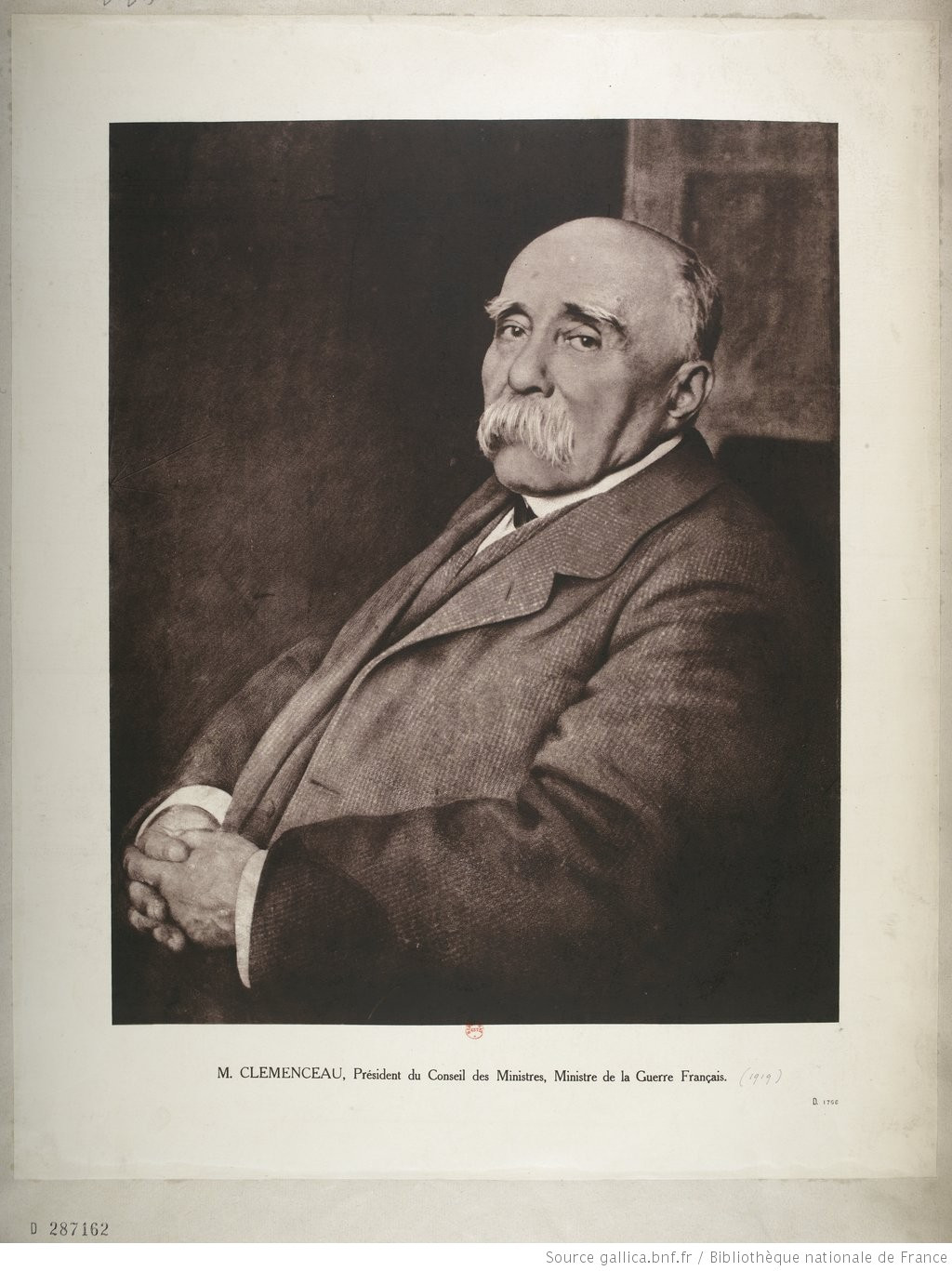

CLEMENCEAU Georges (EN)

Biographical Article

Georges Clemenceau came from a Vendée family spanning several generations and grew up in a family environment strongly marked by the republican political tradition. The figurehead for the young Georges Clemenceau was his father, Benjamin Clemenceau, a fervent republican, anticlerical, and atheist, whose militancy he admired. Beyond his political convictions, Benjamin Clemenceau was also an amateur painter and bibliophile and is often cited as the one who transmitted the taste for art and literature to his son Georges (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 15-37).

School Years and the American Experience

After obtaining a baccalaureate in literature, Georges Clemenceau followed in the family footsteps, particularly those of his father – a doctor practicing in Nantes before inheriting the Aubraie estate and living exclusively from his agricultural land income – by entering the Preparatory School of Medicine in Nantes, on November 1, 1858 for three years of study (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 38; AD 44: IE 99 / IE 100). Subsequently, he continued his studies in Paris where in parallel he began his militant activities by participating in the creation of the pro-republican newspaper Le Travail. Among his comrades were Germain Casse (1837-1900), Jules Méline (1838-1925), and Émile Zola (1840-1902). His revolutionary militancy resulted in legal proceedings; he was arrested in February 1862 and taken to Mazas prison where he was sentenced to two months in prison. This imprisonment did not discourage him from continuing the struggle for his political ideals alongside revolutionary figures such as Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881) and Auguste Scheurer-Kestner (1833-1899).

At the same time, he continued his studies by enrolling in law school and was elected president of the Association of Medical Students. From 1864, he prepared his doctorate with the subject of the generation of atomic elements where he defended the theses of materialism and heterogeneity, following the work of his professor Charles Robin (1821-1885), member of the Academy of Medicine and opponent of the scientific theories of Louis Pasteur (1822-1895). He presented his defence successfully on May 13, 1865. Although he thereafter moved away from a career in medicine, he nevertheless continued intermittently until 1906 to give consultations at the dispensary which he opened in Montmartre in 1871 (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 122), while remaining passionate all his life about questions combining science and philosophy.

Named Doctor of Medicine at just 25 years old, he decided to leave France for a while for another nation forged on revolutionary, democratic, and republican ideals: the United States. In September 1865, Georges Clemenceau embarked from Liverpool for New York (Winock M., 2007, p. 43). There, he tried his hand at journalism by becoming a regular correspondent for the newspaper Le Temps, for which he wrote articles dealing with political news and analysing American society as a whole (Winock M., 2007, p. 44; Clemenceau G., Lettres d’Amérique, 2020). In order to supplement his income, he became a teacher of French and riding for “young girls of good family” (Winock M., 2007, p. 45) in a girls' boarding school in Stamford. One of his students, Mary Plummer (1849-1922), became his fiancée, and the marriage took place on June 23, 1869 in New York (AD 85, État civil, AD2E188/13). The couple moved to France and went on to have three children: Madeleine (1870-1949), Thérèse (1872-1939) and Michel (1873-1964). They separated in 1876, then divorced in 1891 (AD 85, État civil, AD2E188/16).

The Tiger's Political Career: From Revolutionary to Statesman

Georges Clemenceau returned to France just in time to witness the fall of Napoleon III and take part in the events leading to the proclamation of the Republic. He was then appointed by Étienne Arago (1802-1892) as provisional mayor of the 18th arrondissement on September 5, 1870 (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 92).On February 8, 1871, Clemenceau was elected to represent the Seine in the Chamber of Deputies on the lists of the Republican Union alongside Victor Hugo (1802-1885), Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), and Léon Gambetta (1838-1882). After the massacre of the communards in May 1871, he was re-elected on July 30, 1871 as mayor in the 18th arrondissement of Paris, in the Clignancourt district. He was subsequently elected president of the municipal council of Paris in November 1875, then deputy for the Seine in 1876. He was re-elected deputy for the Seine in 1877 and in 1881, then deputy for the Var in 1885 and 1889 (Robert A. and Cougny G., 1889, t. II, p. 126; AD 83: 2 M3341 & 2 & 2 M335). He was one of the radical republican deputies and sat on the far left of the Assembly, advocating, among other things, for the amnesty of the Communards, the abolition of the death penalty, the separation of church and state, the registration of a legal daily duration of working time, the establishment of a right to retirement, the recognition of trade union rights, the prohibition of child labor, and a compulsory and secular public education (Robert A. and Cougny G., 1889 t. II, p. 126). He also opposed the policy of colonial expansion, then embodied by Jules Ferry, the Franco-Chinese wars, and the conquest of Tonkin (1883-1885) (Robert A. and Cougny G., 1889 t. II, p. 126; Journal officiel, July 31, 1885). It was during his terms as a deputy that he acquired the nickname "Tiger" for the ferocity with which he defended his convictions.

Compromised in the Panama scandal in 1892, he was without an electoral mandate after failure in the legislative elections of 1893 (AD 83: 2 M336), and devoted some time to journalism. In October, he replaced Camille Pelletan (1846-1915) as editor-in-chief of La Justice, a radical republican daily that he founded in 1880 with Stephen Pichon (1857-1933). In addition to his daily articles in La Justice, he also published articles in Le Journal, L'Écho de Paris, Le Français, La Dépêche de Toulouse and L'Illustration (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 314). When his newspaper La Justice eventually collapsed, Clemenceau was riddled with debts and became an editorial writer for the newspaper L'Aurore in October 1897, where he distinguished himself by his position in the Dreyfus affair. From December 1897, he took the side of the innocence of the captain alongside Émile Zola (Jolly J., 1966, t. I).

His political career resumed in 1902 with his election as senator from Var (AD 83: 2 M4 9). He then became Minister of the Interior in March 1906. This period was marked by his break with the socialist left led by Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) and the General Confederation of Labor (C.G.T). In October of the same year, he became President of the Council before being removed from power in 1909. He then continued his political career as a senator (AD 83: 2 M4 9) while at the same time founding the newspaper L'Homme libre in 1914, which was renamed L'Homme enchaîné the following year. President of the Senate commission on the Army, his evident patriotism and his attacks against the methods of the high command, defeatists, and pacifists earned him growing popularity. He was recalled to the presidency of the Council as well as to the Ministry of War by President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) on November 16, 1917 (Jolly J., 1966, t. I). He then engaged in a warmongering and patriotic policy. The German defeat was not long in coming and the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. He chose the Hall of Mirrors to sign the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, and obtained the reintegration into the national territory of Alsace and Lorraine, the occupation of the Rhineland and the payment by Germany, recognised as solely responsible for the conflict, of large sums in the form of war "reparations". Despite his victory, the enmities he had created on the left and on the right prevented him from becoming President of the Republic in the elections of January 1920, which were won by Paul Deschanel (1855-1922) (Jolly J., 1966, vol. I).

A Time of Rest: Clemenceau the Traveling Writer

In correspondence with his friend Nicolas Pietri (1863-1954) in 1920, Georges Clemenceau stated: "I think I have done enough for the country, have struggled enough in every way, and therefore have the right to rest.” (MCL, s.c., file no. 3; quoted by Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 862). Clemenceau devoted his time of rest to writing and traveling. It is not his first venture into writing; he already had nine publications to his credit dating from the period between 1893 and 1902 that he devoted to journalism. These publications included many writings and collections of political articles and philosophical works such as La Mêlée sociale (1895) or Des juges (1901), on the Dreyfus affair, but there were also literary works, with his novel Les Plus Forts (1898) and his play Le Voile du bonheur (1901). Some, finally, are at the crossroads of these two genres, almost unclassifiable, such as Le Grand Pan (1896), Au fil des jours (1900) or Aux embuscades de la vie (1903). Even after retiring from politics and journalism, he again took up his pen to write an essay on the Athenian Démosthène (1926) and a book Au soir de la pensée (1927) in which he shared his thoughts on the various philosophical sources and theologies of different human civilisations.

Almost immediately after his presidential defeat,, he undertook the first of a series of great journeys and travelled to Egypt and Sudan between February 4 and April 21, 1920 (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 861). He stayed in Cairo and Khartoum. On September 22, 1920, he left for Ceylon with his traveling companion Nicolas Pietri, responding to an invitation from Ganga Singh Bahadur (1880-1943), Maharajah of Bikaner, to participate in a tiger hunt. Thus began a journey of several months in Southeast Asia, with stopovers in Colombo, Singapore, Jakarta, Bandung, Rangoon, Calcutta, and Benares, then in Allahabad, Delhi and Lahore. He completed his journey by visiting Bombay and Mysore before reaching his final destination, Ceylon. After this journey of several months in Southeast Asia, he returned to Paris on March 4, 1921 (Winock M., 2007, p. 502). He went to England the same year, where he was made an honorary doctor by the University of Oxford on June 22, 1921. Finally, in 1922, he returned to the United States (SHD GR/1/K/841/834) and stayed in New York, Boston and Washington, where he held many political meetings, his expertise as head of state being still much in demand (Winock M., 2007, p. 508). This was his last major trip. Georges Clemenceau died on November 24, 1929 at his Parisian residence (AP 16D 139). He is buried with his father Benjamin Clemenceau in the family property of Colombier, in Mouchamps.

The Collection

At the Sources of a Collection: A Passionate Advocate of Asia

The constitution of his collection of Asian art is related to the taste, if not the passion, that Clemenceau maintained for the Asian continent in general. Clemenceau was a great defender of the Far East through his anti-colonialist stance, which was reflected in his first mandates as a deputy with his condemnation of the French war in Tonkin in 1885 (Journal officiel, July 31, 1885) and which continued during his presidency of the Council in 1907 by the Franco-Siamese treaty which ratified the restitution of three provinces to Cambodia. The same year, he was behind the Franco-Japanese agreement, which ensured Chinese territorial integrity while placing Japan among the great international powers (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 37-38). In addition to this political aspect, he was also passionate about theological study and the civilisational heritage of the Buddhist and Hindu religions, as evidenced by some of his writings (Clemenceau G., Au soir de la pensée, 1927), his participation in several Buddhist ceremonies at the Musée Guimet in 1891, 1893 and 1898 (Kennel K., 2014, p. 186), and his trip to Southeast Asia in 1920-1921. Following his exposure to Islam during his stay in the Middle East, this trip presented the opportunity to this devoted and universal lover of art to satisfy his curiosity about the civilisations of Asia and to visit great heritage sites linked to the Buddhist and Hindu religions, such as the Buddhist temple of Borobudur in Bandung or the place of the first sermon of the Buddha in Benares (Winock M, 2007, p. 500). He brought back art objects from this trip, including the two statues of Buddha and the two schist reliefs donated to the Musée Guimet in 1927 (Cambon P., 2014, p. 228-233; inv. n° MG 17062; MG 17061; MG 17063; MG 17060), as well as an important iconographic documentation composed of albums and more than 250 photographs and postcards (Lentignac L., 2016, p. 153-166). His literary production was marked by the promotion of dialogue between Western and Far Eastern cultures and his interest in Chinese civilisation, the setting of his orientalist play Le voile du bonheur (1901).

Regarding fine arts, his taste for Asian art was similar to that of the late-19th century avant-garde artists (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 77). His entourage included artist friends who were also inspired by Japonisme, such as the painters Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and Claude Monet (1840-1926), whom he visited regularly from 1895 in Giverny and admired his collection of prints and the small Japanese bridge adorning his garden (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 282). Beyond his circle of close friends, he met Philippe Burty (1830-1890), Théodore Duret (1838-1927), and Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896) and frequented Parisian society then populated by japonistes (Séguéla M., 2001, pp. 12-13). It is known that he asked to visit the collection of Edmond de Goncourt (Goncourt E. and J. de, 1889: May 6, 1885, p. 229) who was very fond of Asian art (Duroselle J.- B., 1988, p. 301). His library bears witness to his readings of works by the most important Japanese artists of his time, including L’Art japonais(1883) by Louis Gonse (1846-1921) as well as the monthly journal of Japanese arts Le Japon artistique (1888-1891) by Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 57). He also participated in the exhibition of Japanese engravings organised by the latter in 1890 at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris by obtaining the space and by lending 13 prints from his personal collection (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 57; Bing S., 1890). He was also potentially influenced in his inclinations for Asian art by his association with Japanese nationals, in the context of his political functions as well as in his private circle. Thus, he was initiated into the traditional tea ceremony (chanoyu) at the invitation of the Japanese minister-plenipotentiary stationed in Paris Tanaka Fujimaro 田中不二麿 (1845-1909) in 1889 (Deshayes E., Tokonosuke U., 1895, pp. 7-68). In addition, in 1874, he befriended Saionji Kinmochi 西園寺 公望 (1849-1940), an aristocrat from Kyôto and future Prime Minister of Japan who was then studying law in Paris (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 56), and frequented many japonisantes in social salons, such as the Goncourt brothers and Judith Gautier (1845-1917) (Yoshikawa J., 2011, p. 115-116).

Clemenceau Collector

The admiration of Georges Clemenceau for the arts in general and his taste for Asia is reflected in the constitution of a collection gathered between the early 1870s and 1894, when he parted with a large part of his coins (Delestre M., Leroux E., 1894; Delestre M., Bing S., 1894) following a large debt. He then more moderately pursued his activity as an aesthete collector who liked to surround himself with his collection on a daily basis, in his private houses and apartments as well as in those linked to his functions as a politician (Séguéla M., 2014, p.63). He liked to stage his acquisitions and seemed to take pleasure in arranging them in decorative and original ways (Maucuer M., 2014, p. 103). By mixing his photographs and casts of antiques, testimonies of his Hellenism, with Asian art objects and the works of his avant-garde artist friends, Clemenceau. He thereby created an atmosphere, in which his artistic reverie prevailed over the ensemble’s coherence (Rionnet F., 2016, p. 27-44).

Beyond aesthetic and decorative satisfaction in the act of collecting, Clemenceau found the pleasure of intellectual emulation. Clemenceau, both passionate and informed, was motivated by "the quest for the rare object, the possession of the missing piece or the discovery of a work at his convenience" (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 57) and found scientific satisfaction in the activity of collecting through the study of techniques and the possession of series of object typologies. As a man of letters and a bibliophile, he drew knowledge of his collection from the hundred or so volumes related to Asian art among the some 5,000 in his library (Joxe V., 2016, p. 199-209), including 1,500 still preserved today in the archives of the house of Clemenceau in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard. What he did not manage to learn about his works through his self-taught activity, he sought through the help of his friend Émile Deshayes, assistant curator at the Musée Guimet (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 57).

Little is known about the methods of acquisition in Georges Clemenceau's collection, but a few purchases can be traced. Two series of purchases at the time of public sales are documented, in particular six lots (eighteen books and an engraving) during the third sale of the Philippe Burty collection and three lots (including five kôgô) during the fourth (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 76-77), which took place between March 16 and 28, 1891, respectively at the Hôtel Drouot (E. Leroux, 1891) and in the Durand-Ruel galleries (Delestre M., Bing S., 1891). He also acquired six objects at the sale of the collection of Michel Martin Baer (1841-1904) on June 15 and 17, 1891, including two kôgô, a teapot and a cup (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 79). On the whole, Georges Clemenceau collected a large number of objects of little market value because they were too old or still of little consideration on the Western art market (Maucuer M., 2014, p. 102). He was a client of major Parisian dealers specialising in Asian art, as demonstrated by two preserved invoices (private collection G. Wormser, s. c., Paris), which testify to purchases on October 28, 1891 from Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) and Antoine de la Narde (1839-n. c.). These invoices show that Clemenceau did not hesitate to buy quantities of inexpensive objects; on that day, he acquired seventy objects from Bing, almost exclusively kôgô, for the sum of 773 francs (Duroselle J.-B., 1988, p. 301). Beyond these Parisian purchases, Georges Clemenceau also supplied his collection with objects coming directly from Japan thanks to his friendship with the diplomat Francis-Frédérik Steenackers (1858-1917), then at the French Consulate in the Japanese archipelago, in Kobe, Nagasaki, then Yokohama, himself an enthusiastic collector and collector of Asian objects (Pujos D., 2020). He also received donations, in particular diplomatic gifts, as evidenced in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard by the bronze and ivory statue of Kannon 観音, dubbed “with a basket of fish” (Gyôran Kannon), (inv. CLE 1936001612), offered by the Japanese government in 1907 (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 63-64).

Clemenceau also received donations from his painter and collector friends. Not all of his collection was devoted to Asian art, and his works of modern art reflect his friendship with and admiration for avant-garde and impressionist artists, as evidenced by his relationship with Claude Monet, whose water lilies project for the Musée de l’Orangerie he supported, and whose biography he wrote after his death (Clemenceau G., Claude Monet – Les Nymphéas, 1928). He was also close to Édouard Manet, who painted two portraits of him between 1879 and 1880 (Musée d'Orsay, inv. n° RF 2641; AN 20144790/87; Kimbell Art Museum, inv. n° AP 1981.01). In 1907, he supported the admission of Manet’s Olympia into the Louvre. Through acquisitions, donations, and exchanges, he also owned works by Eugène Carrière (1849-1906), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924), Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) - including a painting of Don Quixote (AN 20144790/74), Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), and Claude Monet - including a self-portrait that he donated to the state in 1927 (Musée d'Orsay, n° inv. RF 2623 – AN 20144790/86).

The Collection of Far Eastern Art

Georges Clemenceau's collection of Asian art was strongly marked by the tendency towards Japonisme and the majority of the works and objects of art collected are of Japanese origin. Nevertheless, this taste is not exclusive and includes, although in smaller numbers, Chinese and Indian objects, as well as some Indonesian, Burmese and Tibetan pieces (Samuel A., Séguéla M. and Taha-Hussein Okada A ., ed., 2014). The collection was created according to the typology of objects, in a mixture of scientific rigour and the obsession of the aficionado. Two main sets stand out in his collection, each bringing together several thousand objects: the kôgô and Asian ceramic art objects - many of which are miniature and related to the ritual around the consumption of tea - and prints.

Clemenceau displayed interest in particular types of ceramic objects, often miniature, which he collected in large numbers. The most important, significant, and singular set remains the three thousand or so kôgô that he assembled in his collection of ceramic art (Maucuer M., 2014, p. 104). Today, it remains the world’s largest collection of these small incense boxes ever assembled by an amateur (Yutaka M., 1977). These implements associated with the tea ceremony in Japan were then present in large numbers on the Western market from the 1880s, where they were appreciated for their wide variety of shapes, materials and colors (Vigo L., 2014, p. 158 -166; Deshayes E., 1909). Clemenceau purchased incense boxes from various traditional places of ceramic production in Japan, including Shigaraki, Tokoname, Bizen, and of course Kyôto, an essential city for ceramic production during the Edo period, of which Clemenceau had models signed by the famous potters Nishimura Zengorô Hôzen (1795-1854) and Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743), at the origin of the Rinpa school (Vigo L., 2014, p. 163-173; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 1960.Ee.613; 1960.Ee.568; 1960.Ee.562). He owned several examples of Oribe-type kôgô with painted decorations (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, inv. no. 1960.ee.1039). Clemenceau's taste for intercultural dialogue seems to find an echo in his collection of kôgô, some of which are of the katamono type, i.e. commissioned models made using moulds in China for the Japanese market and inspired by Chinese ceramic models, at the time much admired (Vigo L., 2014, p. 162-163; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 1960.ee.1185). His collection of Chinese-inspired kôgô also includes Kôchi-style incense boxes, inspired by models from Fujian province but made in Japan. This is evidenced by the turtle-shaped kôgô made of white sandstone with painted decoration in green and yellow enamels from the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (inv. no. 1960.Ee.599), signed by Zengoro Hozen (active 1795-1854), whose pattern is found in similar Chinese ceramics from the Ming Dynasty era (Vigo L., 2014, p. 164-166).

This attraction to incense boxes, used during the tea ceremony or chanoyu, was part of Clemenceau's practice of this ceremony combining tradition, art and philosophy. Traces of it can be found in his collection of around a hundred teapots, mostly Chinese, despite the presence of a few Japanese models (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 152-155). He collected boccaro teapots (紫砂壶 zishahu) in brown or red clay, sometimes etched with decorative motifs or poems and originating from the pottery town of Yixing, north of Shanghai. In addition to the teapots, Clemenceau owned various series of artefacts related to the tea ceremony, of which M. Séguéla (2014, p. 155) details: "a chasen, fifteen kôro (incense burner), two fukusa, three kettles, […], six mizusashi (water reservoirs for tea), thirty-eight cha-ire (pots containing tea) and sixty-three chawan (tea bowls). The rest of his collection of ceramics confirms Clemenceau’s attraction to the fashion of collecting sets of miniature objects, with a set of Chinese porcelain tobacco flasks (Rey M.-C., 2014, p. 256), some of which are kept at the Musée Guimet (inv. no. MG 9752, MG 9753). The Chinese collection, mainly from the Qing period (1644-1912), also includes porcelain and bronze vases, celadon objects, paintings (including three albums from the Summer Palace sold in 1894 (Delestre M. , Bing S., 1894), various pieces of pottery, and a jade cup (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 65).

The second large set of his collection consists of Japanese prints, of which 1,869 pieces were sold in December 1894 (Delestre M., Bing S., 1894). Like many of his contemporaries who admired Asian art, he was interested in ukiyo-e prints, of which he collected a wide range of styles and eras over a period ranging from the beginning of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century (Kozyreff C., Vandeperre N., 2014, p. 95). The major part of his collection was devoted to the landscape print (fukei-ga), represented in particular by Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾 北斎 (1760-1849), of which he had several complete copies of the series of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, and by Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797-1858). He also collected pieces related to the tradition of theatrical performance and portraits of kabuki actors, with prints from the Torii 鳥居派 school and the Katsukawa 勝川派 school, including the actor Onoe Matsusuke in the role of Matsushita Mikinoshin (Collection Musée Clemenceau) by actor portrait specialist Tôshûsai Sharaku 東洲斎写楽 (active from 1794 to 1795), or prints by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川 国貞 (1786-1865) from the series of Sono sugata yukari no utsuhi-e (Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire in Brussels, inv. no. JB.143). Clemenceau was also interested in female portraits, and acquired prints by Suzuki Harunobu 鈴木春信 (circa 1725-1770), Torii Kiyonaga 鳥居清長 (1752-1815), and Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川 歌麿 (circa 1753- 1806). Among these female portraits the presence of oshi-e prints can be noted. These were made of fabric collages, as for Two Women and a Child Contemplating the Moon by Suzuki Harunobu, kept at the Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire in Brussels (inv. no. JP.4316).

Beyond these two large sets, the 1894 sales catalogs give an overview of the breadth and variety of the Clemenceau collection at its peak, presenting, in addition to nearly 3,000 prints, 358 books, 528 paintings, fans and panels, 28 lacquers, 217 netsuke which complete its collection of miniature objects, and 887 miscellaneous objects including, in addition to ceramics, bronzes and carved wooden objects, including 63 theatrical masks (Delestre M., Leroux E., 1894; Delestre M., Bing S., 1894; quoted by Séguéla M., 2001, p. 20-21). Clemenceau had a collection of wooden nô and kyôgen theater masks, which he hung on the walls of his various residences, including the Mask of Masukami (inv. no. AD 638) preserved with four other masks from the Clemenceau collection at the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Nancy (Lacambre G., 2011). He also acquired a few small decorative furnishing objects in lacquer, which are now preserved in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard and are distinguished by the finesse of their execution, including a gold lacquered cabinet (inv. CLE 2005002078 ), a sagedansu (portable picnic kit) in red lacquer enhanced with gold (inv. CLE 2005002076) and a kôdana (incense cabinet) in black lacquered wood decorated with chrysanthemums (inv. CLE 2005002006). His collection also included Japanese bronzes (88 appear at the December 1894 sale; Delestre M., Bing S., 1894) with a pair of foxes, symbols linked to the Shinto cult of the harvest god Inari, preserved in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard (inv. no. CLE 1936001513 and CLE 1936001514) which Clemenceau installed on each side of his front door.

A final set, less significant in number but not in substance, allows us to further measure Georges Clemenceau's interest in Buddhist art and culture. Many of these pieces are of Japanese origin, such as the Surmounted Casket of Shakyamuni Reaching Nirvana in copper from the end of the Edo period conserved at the Musée Clemenceau in Paris. He particularly appreciated the style of Gandhâra, known as Greco-Buddhist, and was interested in the work of Alfred Foucher (1865-1952) while donating four Greco-Buddhist works in schist from Gandhâra to the Musée Guimet in 1927 (Cambon P., 2014, pp. 228-233; inv. no. MG 17062; MG 17061; MG 17063; MG 17060). Some pieces from his collection show, more generally, his curiosity for Indian mythology, such as the copper statuette representing the hero Hanumân acquired during his trip to India and kept at the Musée Clemenceau in Paris (Taha-Hussein Okada A., 2014, p. 205). Finally, he collected, on a more peripheral basis, some Indonesian, Burmese, and Tibetan art objects brought back in part from his travels, such as the reduced copy of the statue of Prajnâpâramitâ by Singhosari and its box, originating from the island of Java in Indonesia and preserved in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard (inv. CLE 1936001608) as well as a Burmese silver briefcase with rich incised decoration and repoussé work preserved at the Musée Clemenceau in Paris (Cambon P., 2014, p. 218-227).

Posterity of a Passion Promoting Asian Art

The collector's passion for the arts of Asia, combined with the politician's loyalty to universalist principles and the scholar's desire to defend a cultural heritage too often seen as inferior in the West, led Georges Clemenceau to engage in the service of a museal and cultural policy for the enhancement of Asian arts. In order to achieve this objective, he used his influence in the highest circles of the state while exerting the collector’s power of donation (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 136-141). In particular, he led the fight for the entry of Asian arts into the Musée du Louvre, which resulted in the opening of the Japanese art department in 1893, then partially supplied by works acquired following Clemenceau’s advice (Musée Guimet, Inv. No. EO 1 and EO 2). At the same time, he supported his friend the industrialist and collector Émile Guimet (1836-1918) in obtaining state subsidies for the creation of his namesake museum, which opened its doors in 1889 (Séguéla M., 2014, pp. 136-141). Clemenceau closely followed the development of this institution, encouraged purchases of works and art objects by the Ministry of Public Instruction especially for the museum, while making donations himself beginning in 1890 (Séguéla M. , 2014, pp. 136-141). He was the museum's first donor of Japanese art in 1904 (E. Leroux, 1904, p. 26-27), and his donations reflect the essence of his personal collection: primarily kôgô, Chinese boccaro teapots, and small art objects, often ceramic, as well as the four aforementioned Buddhist works brought from India (Cambon P., 2014, p. 228-233; inv. no. MG 17062; MG 17061; MG 17063; MG 17060). He was also at the origin of the birth of another museum institution devoted to Asian arts, the Musée d'Ennery, which houses the Asian art collection of his friend Clémence d'Ennery (1823-1898). Wishing to donate her collection to a public institution, she followed the advice of Georges Clemenceau, whom she named her executor, and bequeathed her private mansion to the state in exchange for the constitution of a museum around her collection; Thus, the Ennery museum was opened in 1908 (Alexandre, A., 1908; Séguéla M., 2014, p. 142-149).

The personal collection of Georges Clemenceau experienced a more eventful fate, having not been preserved in its entirety but divided during the collector's lifetime with the sales of February and December 1894 at the Hôtel Drouot (Delestre M., Leroux E., 1894; Delestre M., Bing S., 1894). Many lots were then purchased by specialised Parisian merchants including Florine Langweil (1861-1958), Ernest Leroux (1845-1917), Siegfried Bing, Hayashi Tadamasa 林忠正 (1853-1906), and Michel Manzi (1849-1915) and then swiftly put back on the market. Others were acquired by amateurs whose collections were in turn the subject of public sales, further dispersing Clemenceau's initial collection (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 81-82). However, a number of these amateur buyers of the 1894 sales on the contrary went on to complete the public collections through bequests to national museums, as was the case with Raymond Kœchlin (1860-1931), Edmond Michotte (1831-1914), who bequeathed most of his Japanese collection to the art and history museums of Brussels in 1905 (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 82), and Charles Cartier-Bresson (1853-1921), part of whose collection, including the five Japanese theatre masks acquired during the Clemenceau collection sales in December 1894 (Lacambre G., 2014, p. 111-113; Lacambre G., 2011), was bequeathed in 1936 to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy (inv. no. AD638; AD664; AD 661; AD 632 and AD 667).

Concerning the objects kept after 1894 and those subsequently acquired by Georges Clemenceau, the kôgô seem to have held a particular attachment for him within his collection and were kept until his death. These were also exhibited from 1895 to 1908 at the Musée Guimet, then from 1908 at the Musée d'Ennery (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 59 – AN F/21/4469; F/21/4472). These 2,875 small incense boxes are now kept at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts following their sale in 1938 by Michel Clemenceau to the industrialist Joseph-Arthur Simard (1888-n. c.) who thereafter donated them to the museum institution (Vigo L, 2014, p. 158). The rest of his collection was divided between the pieces that were donated or bequeathed during Georges Clemenceau's lifetime (AN 20150044/75) and those kept in the collector's two homes that since became museums: the Vendée house of Georges Clemenceau in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard and the Parisian apartment at 8 rue Benjamin Franklin, now the Musée Clemenceau. The latter contains almost all the furniture and works of art present at Clemenceau’s death, including forty Japanese works (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 63), following the donation of his children to the foundation of the museum (MCL, s. c., file n° 7), which has managed the institution since it opened its doors to the public in 1931 (Lemieux A., 2019). The fishing house at Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard was acquired by the state along with its land between 1932 and 1935, while its furnishings were donated by Georges Clemenceau’s three children to national public collections.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne