JULLIOT dynastie des (EN)

Biographical article

The first in the Julliot dynasty, Claude-Antoine was born into a wealthy family in the village of Poinchy, in Burgundy, near Chablis. His father Claude, a procureur, died before 1712, leaving his wife Étiennette Mercier (1658–1741) to bring up their children on her own. Little is known about Claude-Antoine’s training, other than the fact that he became a marchand mercier (dealer) on 14 October 1719 (Lemonnier, P., 1989, p. 41) and that he received from his maternal uncle, Edme Mercier, a bourgeois dealer from Paris, the significant sum of 28,000 livres (AN, MC, AND/XXXIX/317). On 13 December 1721, he married Françoise Février (1702–1736) (AN, MC, AND/XXXIX/316), the daughter of Jacques Février, a procureur in the parliament of Paris, and granddaughter of Guillaume Daustel (1646–1718), the famous and wealthy marchand mercier at the end of the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715). In 1721, the couple rented from Jean-Baptiste Lemarié Daubigny, the king’s councillor and secretary, a boutique located on the Quai de Conti in Paris, on the corner of the Rue Guénégaud, for the sum of 1,900 livres per annum, where Claude-Antoine had a shop until 1747 (AN, MC, AND/XIX/657). But, on 22 September 1736, Françoise Février passed away at the age of thirty-four, leaving behind five children. A post-death inventory was drawn up as of 7 December 1736 (AN, MC, AND/XXXIX/353). In 1737, Claude-Antoine married Élisabeth Bardeau (AN, MC, AND/XXXIX/355). In 1751 (AN, MC, AND/CXII/705/A), he moved into Rue des Fossés-Monsieur-le-Prince, in a shop near the former mansion of the Prince de Condé. He was still living at this address when he died on 14 March 1760 (AN, MC, AND/X/540). As of 1751, Claude-Antoine had already drastically reduced his activity as marchand mercier and left his son Claude-François to run the business.

Born in 1727, Claude-François was the youngest of five children of Claude-Antoine Julliot and Françoise Février. Orphaned by his mother’s death at the age of nine, he followed in the footsteps of his father and became a dealer circa 1752. At that time, Claude-François Julliot had already left the family’s district on the Left Bank and crossed the Seine, moving to the Quai de la Mégisserie, which was more fashionable at the time. On 6 February 1753 (AN, MC, AND/XXXVI/474), he married Marguerite Martin (1732–1776), a native of Ribecourt (Oise), a village near Noyon. In 1760, he left the Quai de la Mégisserie for a more prestigious and fashionable address, in a house on the Rue Saint-Honoré, on the corner of the Rue du Four. It was here that he had a shop called the Curieux des Indes. Marguerite Martin died on 27 May 1776 and Claude-François was obliged, due to financial problems, to draw up the post-death inventory of his wife as of 5 November 1777 (AN, MC, AND/X/666) and auction off the stock in his shop on 20 November. Then Claude-François abandoned his profession as a marchand mercier and handed the business over to his son Philippe-François. He died in his house on the Rue des Deux-Écus on 30 June 1794 (Lemonnier, P., 1989, p. 41).

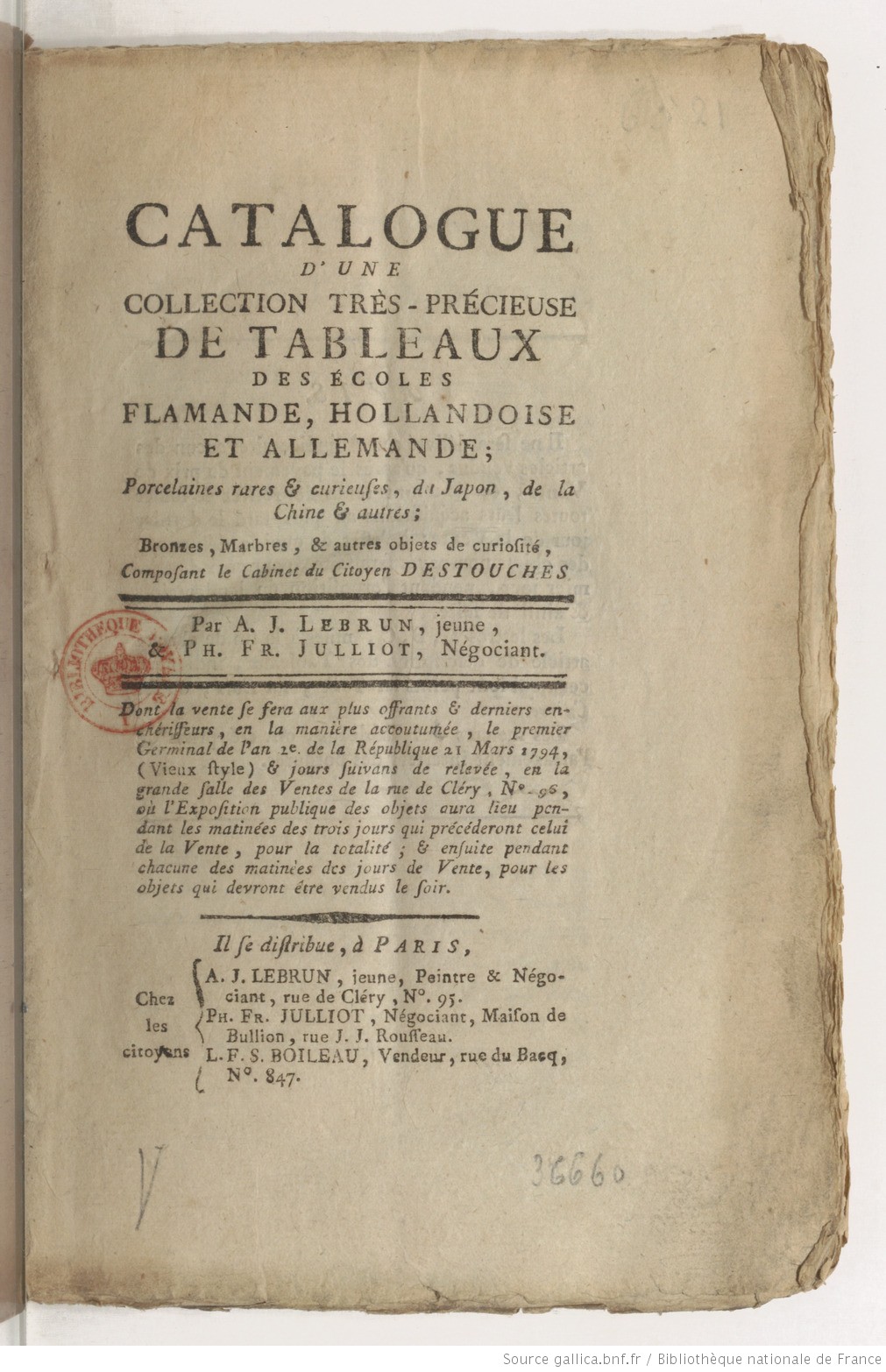

The last of the dynasty, his eldest son, Philippe-François, was born in 1755. He became a marchand mercier circa 1777 and took over the business, the Curieux des Indes, on the Rue Saint-Honoré on the corner of Rue du Four, until 1793. He also developed his activity as an expert in auctions until the end of the 1780s. The outbreak of the Revolution obliged him to move into the family house on the Rue des Deux-Écus, then on the Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau. In 1799, he went bankrupt and stopped running his business at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Pradère, A., 2005, p. 27). He died on 6 January 1836 (Pradère, A., 2005, p. 29).

Claude-Antoine

Practising their métier throughout the eighteenth century, the Julliots were incontestably very important Parisian marchands merciers (dealers). True to their profession, the Julliots sold a highly diverse range of objects, pictures, Boulle marquetry furniture, gilt bronzes, European and Far-Eastern porcelain wares, lacquered objects, bronze and marble sculptures, and many other curiosities. The first in the dynasty, Claude-Antoine, began his activity on the Quai de Conti in 1721. It appears that, in 1722, he acquired objects from the sales held by the Compagnie des Indes in Nantes, in particular furniture and varnished panels or so-called lacquered items from Canton (Wolvesperges, T., 2000, p. 166). It is highly likely that he also bought Oriental porcelain wares from the same place. His wife’s post-death inventory in 1736 gives us a very good idea of his stock at that time. The evaluation of the goods stocked in the shop was carried out by Simon Poirier, the father of the famous marchand mercier Simon-Philippe Poirier (1720–1785). Some Boulle marquetry furniture, other furniture, objects made from pietra dura, and rock crystals for chandeliers are listed in the inventory. But most of his stock comprised porcelain items and Far-Eastern lacquer objects. Hence, there was a total of no less than 3,736 Oriental porcelain wares, with or without mounts, in bronze or silver, and 202 lacquer objects, such as cups, boxes, and saucers (AN, MC, AND/XXXIX/353). The succinct descriptions in the inventory make it difficult to precisely identify the works, but particularly noteworthy were many Japanese porcelain mixing bowls and bowls with silver decorations, coloured Chinese porcelain wares, China white wares from Dehua, Chinese porcelain wares with turquoise glazes, blue and white wares, and celadons. Between 1739 and 1744, Claude-Antoine became a supplier to the French Crown. For the Château de Compiègne, he sold in 1740 a wooden Chinese commode for the cabinet of King Louis XV (1710–1774) (AN, O1/3313, fol. 22). In 1741, he provided for the Château de Choisy another so-called ‘China varnish’ commode (AN, O1/3313, fol. 67vo), as well as many Chinese porcelain wares (AN, O1/3313, fol. 46vo–47). As of 1752, Claude-Antoine left his son to run his business. However, upon his death in 1760, he still ran a boutique on the Rue des Fossés-Monsieur-le-Prince. As for his wife in 1736, an inventory was drawn up on 20 March 1760. Jean-Louis Berouin Villercy, a marchand mercier (dealer) based on the Rue Saint-Honoré, was entrusted with carrying out the evaluation of the objects in the shop. However, only 141 objects remained, including 109 Oriental porcelain articles, comprising mainly urns and Chinese blue and white porcelain cornet vases and some Japanese porcelain mortars (AN, MC, AND/X/540).

Claude-François

His successor, Claude-François Julliot, benefitted from his father’s renown. In 1752, he moved to the Quai de la Mégisserie. Nevertheless, Claude-Antoine supported his son financially and in January and November 1754, lent him the sums of 4,200 and 6,988 livres to ‘use for business’ (AN, MC, AND/CXII/710).

In 1760, Claude-François Julliot moved to the Rue Saint-Honoré on the corner of the Rue du Four, to the Curieux des Indes shop. After his father’s death, business boomed and he diversified his activities, in particular working as an expert for the evaluation and drafting of auction catalogues; as he did in 1767, for Jean de Jullienne (1686–1766), when Claude-François Julliot drafted the catalogue raisonné of the famous collector’s porcelain wares, ancient lacquer objects, and Boulle furniture. He bid for many lots in this sale, both for himself and on behalf of famous collectors such as Augustin Blondel de Gagny (1695–1776), Pierre-Louis-Paul Randon de Boisset (1708–1776) and Louis-Marie-Augustin, Duc d’Aumont (1709–1782). At that time, he had a prestigious clientele.

In 1768, Louise-Jeanne de Durfort de Duras, Duchesse de Mazarin (1735–1781), acquired a large quantity of objects and, in particular, Oriental porcelain wares from Claude-François Julliot. On 6 February 1773, she purchased two urn-shaped vases, with snake handles carved directly in the material, and ancient celestial blue Chinese porcelain for 720 livres (private collection) (Vriz, S., 2011, pp. 58–61).

On 5 November 1777, Claude-François was obliged to draw up the post-death inventory of his wife, who had died on 27 May 1776. Jean-Louis Berouin Villercy and Simon-Philippe Poirier carried out the evaluation of the objects in the Curieux des Indes, comprising around 1,586 objects, including 1,086 porcelain items and almost 90 lacquer and bronze articles, marquetry furniture, in particular furniture made using the technique developed by Boulle, and hard stones, often imported from the East, such as porphyry, granite objects, agates, and marble antiques (AN, MC, AND/X/666). As of 20 November 1777, the entire contents of the shop were presented at auction, providing us with a very precise description of Claude-François Julliot’s business activities. The auction consisted of 520 lots of oriental porcelain wares and 58 lots of objects and Japanese or Chinese lacquered furniture, such as lot 639, which concerned a Japanese lacquer ‘kiosk’ containing an incense box (Musée du Louvre, Paris, MR380–86; MR380–87), whose vermeil mount was made by the Parisian goldsmith Antoine Dutry between 1775 and 1777.

Julliot’s loyal clients attended the sale. Hence, the Duchesse de Mazarin purchased several articles, including a pair of Chinese celadon porcelain vases dating from the fifteenth century (private collection) (Vriz, S., 2018, pp. 72–73). Julliot also sold Japanese ceramic wares, such as a pair of shells transformed into Arita porcelain potpourri vases, dating from the end of the seventeenth century, which can be seen amongst the articles held in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles (inv. 77.DI.90.1–2) (Wilson G., 1999, pp. 80–84). His sale included ceramic wares with Kakiemon decorations, which were very popular in the eighteenth century, as well as all the different types of Asian porcelain objects that could be acquired during the second half of the Enlightenment.

Julliot also traded in Boulle marquetry furniture and furniture in the Boulle style. Indeed, he supplied in September 1777, for the Comte d’Artois’ bedroom in the Palais du Temple, a Boulle-style commode made by Étienne Levasseur (1721–1798) (Musée du Louvre, Paris, on permanent loan from the Château de Versailles, inv. 2012.V 3581) (Durand, J., Dassas, F., 2014, p. 404). Claude-François retired from his business shortly after 1777. He died, almost destitute, in 1794, in his house on the Rue des Deux-Écus.

Philippe-François

The last of the dynasty, his eldest son, Philippe-François, succeeded him after 1777 and took over the family shop in the Rue Saint-Honoré. Even though he sold, like his forbears, porcelain and lacquer objects, Philippe-François specialised in particular in selling Boulle marquetry furniture, and in pietra dura and other hard stone objects, as attested by a watercolour drawing held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which bears the inscription ‘this drawing was made on 7 September 1784 under the direction of Philippe-François Julliot, son’ (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, inv. 25180). This project bore similarities with a commode attributed to Adam Weisweiller that belonged to the collections of the King of Sweden in Stockholm (inv. O II St 1) (Pradère, A., 1989, pp. 34–36 and p. 398, fig. 491). Like his father, Philippe-François was also known for his expertise in major auctions of the most precious cabinets, during the last twenty years of the eighteenth century. He worked in particular on the sales of Louis-Marie-Augustin, Duc d’Aumont (1709–1782), in December 1782, that of Louis-François-Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duc de Richelieu (1696–1788), in December 1788, and that of Emmanuel Félicité de Durfort, Duc de Duras (1715–1789), in December 1789. An analysis of these auction catalogues gives us a good idea of Philippe-François’ business activities with regard to lacquer objects and Oriental porcelain wares. As he himself had a cabinet, he often placed bids for himself and on the behalf of others. The porcelain and lacquer objects that the collectors came to buy at the Curieux des Indes, the precursor of today’s antique shop, were not only objects produced for Julliot, but also second-hand objects.

In 1782, attesting to his reputation as a connoisseur of porcelain wares, hard stones, and Far-Eastern lacquer objects, Louis XVI entrusted him and his confrère, the dealer Alexandre–Joseph Paillet (1743–1814), with the task of selecting, evaluating, and acquiring for the best price more than fifty lots at the Duc d’Aumont sale to establish the future museum, in accordance with the king’s wishes. The Revolution obliged Philippe-François to leave the Rue du Four and move to the Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau. His bankruptcy in 1799 (Pradère, A., 2005, p. 27) was followed by two sales of his stock in March and November 1802.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Personne / personne

Personne / personne

Personne / collectivité