MACIET Jules (EN)

Family and training

Jules Maciet was born on 13 November 1846 in the Rue Cambon, in Paris. He was the only son of Charles Jules Maciet (1817–1884), an annuitant who came from Provins, and Olympe Gabrielle Maciet (1824–1904) née Jean. His youth was spent between Paris and Château-Thierry living with his parents ‘who had a passion only for charity, books, and dogs’ (Aman-Jean, F., 1967, pp. 8–9). Educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, he would spend his leisure time in the Louvre at the age of twelve, and was thoroughly familiar with the museum by the age of fourteen; ‘at the age of fifteen he studied the art of carpets, tapestry, illuminated manuscripts, and Persian miniatures. At the age of sixteen, he studied ceramics and porcelain’ (Aman-Jean, F., 1967, p. 9). He started to frequent dealers while in school and began to collect objects at the age of eighteen. In 1865, he began to keep a record of his artistic acquisitions and expenses (UCAD, F 117), in which he provided a succinct description of his purchases and their prices; the letters V (for ‘vente’, or sale) or M (for mercier, or dealer) specify the origins of the acquisitions. Between July and November 1868, he went on the Grand Tour, travelling in Germany and Italy, where he visited the museums. The letters he sent to his family and friends illustrate his thorough familiarity with the collections held in Parisian museums, which he refers to in comparison with the works he discovered (Sirieys, J., 2004, pp. 9–12). Destined by his family to become a notary, he studied law and defended his thesis on 28 April 1869, but never began his career as a legal expert, as he preferred to devote his life to art. In 1869, he worked for the master auctioneer Pillet, then as a clerk to the picture dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) (Kœchlin, R., 1912, p. 5). During the 1870 war, he enlisted in the Mobile Guard (Maciet, C., 1913), then decided to live from his annuity and devote himself to his collections. His personal tastes initially directed him towards the minor Dutch masters, then towards eighteenth-century art, Persian art, and tapestries. He was also involved with some contemporary artists: the painters Aman-Jean (1858–1936), his cousin, and Albert Besnard (1849–1934), and the sculptors René de Saint-Marceaux (1845–1915) and Alfred Lenoir (1850–1920) (Kœchlin, R., 1912, p. 24).

His involvement with museums

More than a simple collector, Maciet was a magnate benefactor who had a passion for purchasing works—which he obtained from dealers and auction rooms—for museums to enrich their collections. His greatest success occurred in 1885, when he bought the portrait of Anne de Beaujeu, attributed to the Master of Moulins (UCAD, F 117), for 357 francs at the La Béraudière sale, which in 1888 he donated to the Louvre, where the other panel of the diptych was held. The first museum Maciet became involved with was that of Château-Thierry. As soon as it was established in 1876, he primarily donated pictures and graphic works, which were often associated with the town and its history. His role was so important in the first years that the painter and art critique Frédéric Henriet (1826–1918), the museum’s first curator, described him as a veritable founder of the institution (Henriet, F., 1900, p. 6). The list of museums that benefitted from his generosity both in Paris and the provinces is quite impressive: Gray, Clamecy, Sens, Dijon, Lille, Aubusson, Orléans, Rouen, Péronne, Limoges and, in Paris, the Louvre, the Musée Carnavalet, the Musée de l’Armée, and the Musée du Luxembourg (UCAD, F 117; Sirieys, J., 2004, p. 36). The many donations he made to museums led him to change the layout of his acquisitions book as of 1878: they were no longer indicated in the footnotes, but instead on the right-hand page, along with the date, which was sometimes very different from the acquisition date (a sixteen-year gap for a portrait of a woman bought in 1878 and donated to the Louvre in 1894), whilst the purchases were listed on the left-hand page.

Jules Maciet and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs

Jules Maciet is best known for the role he played at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. On 13 November 1878, he underwrote 500 francs as co-founder of the Société du Musée des Arts Décoratifs (UCAD, A2/7). In 1882, he was a founding member of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, which was the result of a merger between the company and the Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts Appliqués à l’Industrie (UCAD, A3/35). Elected to the board of directors in 1885 (UCAD, A4/90), he chaired the museum’s committee from 1895 to 1911. Close to Georges Berger (1834–1910), the President of the institution, and the curators Paul Gasnault (1828–1898) and Louis Metman (1862–1943) as of 1898, he played an active role in the acquisitions policy. When it was founded in 1890, he was a member, then president of the education committee (UCAD, A6/6), and as such worked closely with the library’s director Alfred de Champeaux (1833–1903). At the end of the 1880s, he was one of the library’s main donators and the leading contributor to the iconographic collection. In the 1900s, he drafted the project to establish the library on the Rue de Rivoli (UCAD, B6/85) and the catalogue’s layout (UCAD, F 5). Between 1880 and 1911, Jules Maciet gave the Musée des Arts Décoratifs a total of almost 350 donations, and a bequest that comprised more than 2,500 objects, added to which were countless donations made to the library. In his acquisitions book, most of the purchases he made in the 1880s were intended for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Maciet donated objects to help the museum compile its collections: mainly models that demonstrated ‘compositional logic, and the suitability of the material for the object and of the decorative aspects for its utility’, because for him the museum’s main purpose was to help educate the taste of artists and the general public (Koechlin, R., 1912, p. 11). The objects were acquired specifically for the museum or came from his private collection. He was particularly generous when it came to certain series, such as Persian art, which he discovered in 1878 (Koechlin, R, 1912, p. 12), especially ceramic wares, miniatures, and carpets. At certain points in his life he donated entire segments of his collection: in 1903–1904, he gave away all of his faience pieces, carpets, and tapestries after he moved to a different residence (Koechlin, R., 1912, p. 13; UCAD, F 166).

Jules Maciet and the Société des Amis du Louvre

A regular donator since 1888, he contributed in 1897 to founding the Société des Amis du Louvre to help the Musée acquire works of art that would otherwise have been acquired and transferred abroad due to a lack of funds. Vice-President of the conseil at the end of the same year (Musée du Louvre, 1997, p. 53), he was appointed President in 1910 and was appointed on this occasion as a member of the Conseil des Musées Nationaux, but only for a few weeks, because he died suddenly on 15 January 1911. Jules Maciet’s role as a donator to French museums was so remarkable that one year after his death, in 1912, an exhibition devoted to him was held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. One of the six rooms was devoted to Oriental objects, carpets, ceramic wares, and miniatures (Sirieys, J., 2004, p. 47).

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

The collection

Asian objects were naturally included in the acquisitions made by Jules Maciet, who was a man of his times, and as part of his lifestyle, but he was never considered a specialist or a collector in this field. In 1867, he may have acquired his first object at the Exposition Universelle, a Japanese porcelain bottle with blue decorations (UCAD, F 117). Subsequently, he mainly acquired other works from dealers (UCAD, F 117), whose names are unknown, with the exception of some rare labels that are still glued onto certain objects. Some of his acquisitions were made in auctions. From 1880, when the Musée des Arts Décoratifs was set up in the Palais de l’Industrie, until his death in 1911, Maciet contributed to the establishment of the Asian collection. As of 1881, he acquired objects to make direct donations. As of 1882, ‘Art chinois et japonais’ was an entirely separate category in his book of donations. Each year between 1880 and 1887, he donated between three and twenty-four objects; then, from 1888 to 1910, his generous donations were no longer made on an annual basis and were restricted to some objects on each occasion. In total, he donated or bequeathed just under two hundred Asian objects and textiles of the 2,561 items listed in his book of donations to the museum (UCAD, F–166) and in the list of bequeathed objects. In the field of extra-European arts, Jules Maciet is still famous in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs for his exceptional donations in the field of Islamic carpets (Day, S., 2007, pp. 302–309). Although Asia was not his favourite specialisation, his universalist vision of the collection in the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs seemed to appeal to his sense of curiosity. He was interested in Asian arts in all their diversity, and in order of numerary and qualitative importance he collected Chinese objects (almost 60% of the ensemble, with Japanese and Indian objects representing 37% and 5% respectively). Maciet was primarily interested in ceramic wares and particularly Chinese and Japanese porcelain, which account for more than 60% of the almost two hundred objects. This was followed by bronzes, metals, and cloisonné objects (15%), then the Japanese netsuke. Lastly, he also acquired some wallpapers, painted or gilded wooden objects, such as shelves, a small Japanese altar, a Chinese stele, untreated wooden or gilded Japanese statuettes, and a theatre masque made from lacquered and gilded wood. Small-format paintings on silk, hardstones, carpets, two patterned or embroidered panels, and two textile samples make up the rest and appear to attest to his universalist approach. With regard to prices, it is feasible that certain acquisitions were dictated by the fact that some of the objects were acquired cheaply, a completely different approach to that adopted for his very costly acquisitions of Anatolian carpets.

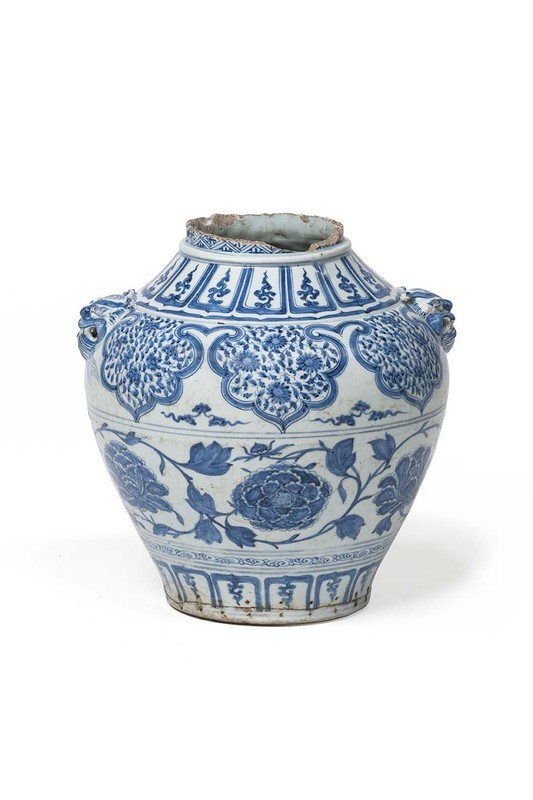

Maciet participated in the compilation of the Asian ceramic collection, a material he was familiar with, out of a desire to provide models, which explains why he assembled series over several years before giving them to the Musée. Hence, in 1884, he gave on two occasions two dozen Chinese and Japanese saucers, plates, and dishes, ensembles he had assembled since 1881, as he made his discoveries. With his contemporary approach and in the light of the evolution in scientific knowledge, a third of the articles have a certain, if not remarkable interest. As for the remaining works, they retain their role as sources of inspiration via the series assembled, initiated, or completed by Maciet. In the first group, it is worth mentioning an ensemble of around thirty porcelain objects with cobalt blue decorations under a glaze: a jar with a blue design, one of the two remarkable porcelain items dating from the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), now held by the Musée (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, p. 31); an ensemble of porcelain objects dating from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) made for the Chinese market, and other porcelains from the Wanli era of the kraak type, intended for export to Europe; some articles from the Kangxi period, and a Japanese vase produced in Hirado with a decoration of mountain landscapes. It is believed that, from 1878 to 1893, Maciet’s donations represented 20% of the acquisitions of Japanese porcelain objects by the Musée, including many examples of articles intended for export produced in Arita with Imari style decorations, as well as some seventeenth-century porcelain articles of the ko–Kutani (Old Kutani) type (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2018, p. 118). In the field of metal objects, Maciet enriched the collection with some Japanese bronzes and rare Indian statuettes that are now held in the Musée. However, the Chinese bronzes predominate and include some fine articles, including a late bronze <i>you</i> from the eighteenth century (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, p. 62), and some Buddhist statuettes, figures of Guanyin (monks) in gilded bronze (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, p. 57), as well as a painted bronze warrior dating from the Ming dynasty. His interest in small carved figures—both of Chinese and Japanese origins—is evident and, amongst the twenty or so examples, they are made of stoneware, porcelain, untreated wood, gilded wood, and painted or gilded bronze. In the field of the Japanese art of miniature sculptures, he donated in 1887 fifteen netsuke bought in 1877 and 1878. Lastly, the name Maciet is also linked to the field of Chinese wallpapers, thanks to two panels representing ducks in a landscape and two panels, which are now together, representing a flowering tree full of birds (the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, p. 25 and p. 27, no. 19), the only complete examples of wallpaper made in China in the eighteenth century and exported to Europe. The latter, which decorated his dining room, as well as the bronze you and a seventeenth-century Japanese porcelain bottle (inv. 17875), were part of the last seventeen Asian works to be integrated into the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, those of his bequest, which adorned his residence.

As of 1892, he participated in the compilation of the library’s Japanese collection. He donated the hundreds of pages of albums of kimonos or textile models that are glued in the iconographic collection (Coignard, J., 2002, p. 27). In 1898, five albums of models of kimono embroideries were added to the collection. Lastly, in 1908, he gave the Musée a splendid album (of remarkable dimensions) of Chinese gouaches executed on ‘rice paper’ dating from the beginning of the nineteenth century, which was given to the library in 1920 (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, p. 8, 82, and 85). Donations of Asian objects to other museums were rarer. In 1879, he gave the museum at Château-Thierry the blue Japanese porcelain bottle he had bought in 1867 (UCAD, F 117), five netsuke, and a small Chinese dragon made from lava stone (Société Historique et Archéologique de Château-Thierry, 1880, p. 94). In 1894, he gave the Musée du Louvre—for the collection of Asian art assembled by his friend the curator Gaston Migeon (1861–1930)—a wooden Japanese Buddha acquired in 1884 (UCAD, F 117). Lastly, he bequeathed five Japanese ceramic objects to the Musée de Dijon (Sirieys, J., 2004, p. 45 and annexes p. 50).

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique