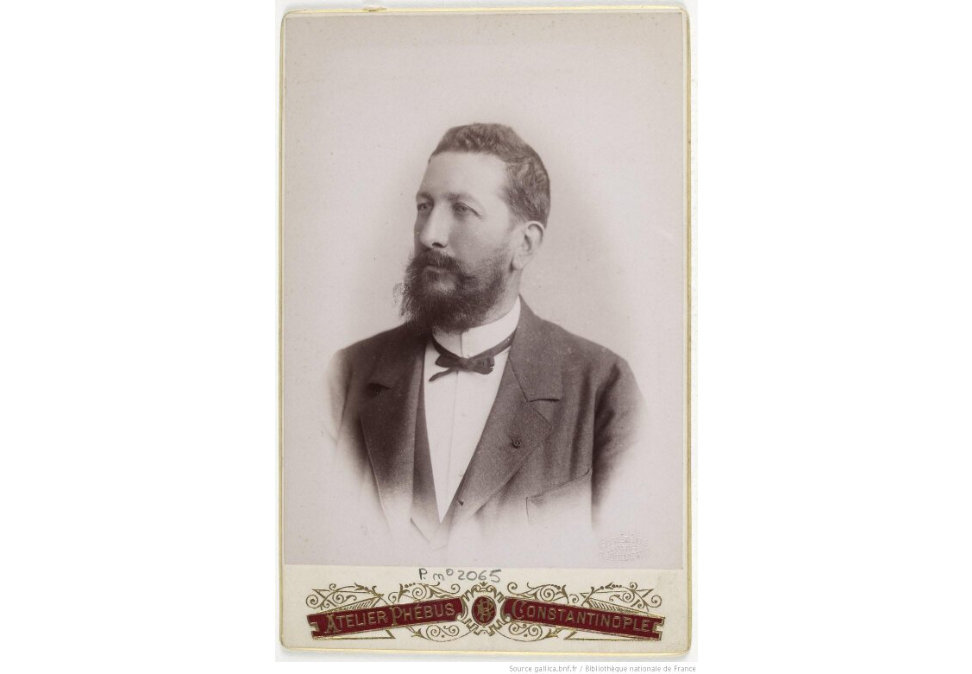

CHANTRE Ernest (EN)

Biographical article

In the opinion of Salomon Reinach (1925), Ernest Chantre was “the next to the last survivor (…) of what one could call the “heroic period” of Prehistory. The scholar assuredly counts among the most influential people in the world of anthropology and archaeology at the end of the 19th century in France and was also recognised as one of the foremost specialists of his times on the subjects of the Caucasus, Armenia and Anatolia.

Born in Lyon in 1843, Chantre steered his studies towards the natural sciences and, under the influence of Paul Broca and Gabriel de Mortillet, became fascinated with anthropology and Prehistory. His early research consisted of palaeoethnological studies conducted in the north of Dauphiné, the area surrounding Lyon, and geological studies of ancient glaciers and the erratic terrain they left behind, work which led to his earliest publications in 1866 (Pittard E., 1925).

Possessing a degree in the sciences, Chantre was appointed as attaché to the Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Lyon in 1871, later becoming assistant director in 1877, a post he held until 1910. He was a lecturer in anthropology at the Faculty of sciences of Lyon in 1871 where he taught until 1908. In 1881, with the support of Paul Broca and the minister of public education, the scholar created the laboratory of anthropology of the Faculty of Sciences of Lyon at the same time as the Société d’Anthropologie de Lyon before being elected to serve as its secretary general. Beginning in 1892, he also taught ethnography at the Faculté des lettres (Broc N., 1992). Finally, in 1901 he defended a doctoral thesis in Science at the university of Lyon dedicated to L’Homme quaternaire dans le bassin du Rhône (Quaternary man in the Rhone basin), in 1903, he was engaged as a lecturer in anthropology, created under the framework of higher education founded by the city of Lyon.

In 1869, After Emile Cartailhac purchased the journal Matériaux pour l’histoire positive et philosophique de l’Homme and he had taken over the title Matériaux pour l’histoire primitive et naturelle del’Homme, Chantre was increasingly asked to collaborate, eventually becoming co-director in 1873. In parallel, he took over the direction of the Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Lyon and contributed to many other scientific publications.

Focused on the definition of universal methods at the service of scientific knowledge, Chantre was a pioneer in the improvement of archaeological mapping and, during the Stockholm congress of anthropology and prehistory (1874), proposed the adoption of a Légende internationale pour les cartes préhistoriques (International key for prehistoric mapping) (Gran-Aymerich E., 2001).

Chantre considered that the advances in anthropology and archaeology were indissociable from field work, which he relied upon to accumulate empirical knowledge upon which he based his more theoretical and systematic studies in his publications and teaching. This is why, in 1873, at his own expense, he undertook several exploratory trips, accompanied by his wife Bellonie, who would play an active role throughout his career and publish the story of some of their explorations. One of the most important travels during this period was his 1873 mission, conducted in Greece and Turkey (Chantre, 1874a). After 1878, Chantre obtained an official mission practically every year from the ministère de l’Instruction publique. This was the time when Prehistory was gradually gaining its autonomy and when the interests of European travellers to more inaccessible regions of the Near East were gradually changing in nature. More than “curiosities”, henceforth what counted most were archaeological and anthropological observations that were being accumulated by Russian scholars and their French and German counterparts, in order to arrive at an ever more detailed understanding of ancient cultures and the evolution of modern populations.

The discovery of the Caucasus and surroundings

Prehistoric research in Russia gained momentum from the international congress and the Moscow anthropological exposition organised in 1879. On this occasion, undoubtedly owing to his renown in scientific circles, Ernest Chantre was invited to participate in the congress and obtained from the ministère de l'Instruction publique a free mission “to undertake studies on anthropology, at Kasan [sic], in the Caucasus, in Crimea and in Turkey” (AN, F17/2946c). Accompanied by the naturalist J. de Poutschine, he carried out digs in the region of Tiflis (currently Tbilissi), in Georgia, in the company of Frédéric Bayern and gave an account in his report of 1881 Recherches paléoethnologiques dans la Russie méridionale et spécialement au Caucase et en Crimée (Palaeoethnological research in southern Russia and especially in the Caucasus and Crimea).

Chantre, having Subsequently decided to extend his investigations to southern Armenia before returning to the Caucasus” (Chantre E., 1885, p. XXXII), obtained by a decree of 29 March 1881, a new subsidised mission to explore regions neighbouring the Caspian Sea and Mount Ararat with an indemnity from the state of 10,000 F and a few competent collaborators such as commander Barry, responsible for Photography and Donnat-Motte, a naturalist at the Muséum de Lyon (AN, F17/2946c). The exchange of correspondence with Xavier Charmes, director of the secretariat and accounting for foreign missions at the ministère de l’Instruction publique, attest to the success of this exploration of encyclopaedic breadth, blending ethnographic and anthropological observations with archaeological works. Chantre adapted his itinerary owing to the bad sanitary conditions of the regions he was crossing and entered Armenia via Upper Mesopotamia and western Kurdistan. From Lake Van, he arrived at the southern foothills of Mount Ararat, crossed the border between Igdir and Erevan, before arriving at Tiflis (Tbilisi) and undertook digs in the great necropolis of Mchketi. The scholar very quickly dispatched ten cases of ethnographic and zoological collections as well as archaeological and anthropological photographs to France, whilst waiting to proceed to a new dispatch composed of the results of his digs dans les nécropoles préhistoriques de l'Osséthie et de la Cachétie (in the prehistoric necropolises of Ossetia and Cachetie) (AN, F17/2946c) (Chantre E., 1881).

Arriving in July in Koban (North Ossetia), Chantre took the best possible advantage of his collaboration with Frédéric Bayern and colonel Olchewski to carry out methodical digs, which he had not been able to do during his 1879 mission. In his correspondence with the ministère de l'Instruction publique, he enthusiastically signalled his very positive results (AN, F17/2946c), emphasising the fact that cette nécropole (...) paraît devoir ouvrir à l'archéologie préhistorique, non seulement du Caucase, mais de l'Occident tout entier, des orizons [sic] des plus nouveaux et des plus importants (this necropolis (...) seems like it ought to open for prehistoric archaeology, not only in the Caucasus, but in the entire West, newer and more important orizons [sic]”).

His sojourn in Moscow, where he was shown the earliest discoveries found in the Caucasus, as well as his collaboration with Gustave Radde, director of the Caucasian Museum, Smirnow and Bayern, enabled Chantre to use the observations of his colleagues and to already begin to make comparisons with the civilisation du premier âge du Fer florissante dans le centre de l’Europe ( civilisation of the early Iron Age flourishing in the centre of Europe)(culture of Villanova in Etruria or the one of Hallstatt in Austria) based on the similarity of certain objects such as fibula with a simple arc, animal figurines, decorative patterns in svastika or spiral form (Chantre E., 1881, p. 17)… In the necropolis extending over two hectares near the village of Upper Koban, the archaeologist dug large trenches and brought to light twenty-two sepulchres. Ten among these enabled him to observe their architectural organisation and the composition of funerary furniture. He remarked in particular that there was no trace of incineration. Both in his publications and his correspondence, Chantre insists on the fact that the funerary furniture was found still perfectly in place (MAN, SRD, Correspondence Chantre, letter of 24 March 1882 to G. de Mortillet; Chantre E., 1882, p. 241-265). These discoveries were swiftly and favourably echoed, including to a curious public, as some of the findings were exhibited in 1889 in the Retrospective Exposition of Work, section of the Exposition universelle de Paris.

Affirmation of the method

Following the refusal of another subsidised mission to investigate Armenia, Chantre obtained a new mission for himself and his wife, a mission au Caucase et dans les provinces voisines de la Turquie d’Asie à l’effet d’y poursuivre leurs études ethnologiques et anthropométriques (“mission to the Caucasus and in the neighbouring provinces of Asian Turkey and for the purpose of continuing their ethnologic and anthropometric studies) (AN, 2946c). Therefore, this trip was already and especially for anthropological and even anthropometric purposes as Chantre was recording the measurements of a vast sampling of the populations he encountered over the course of his exploration. He was doing this in order to classify the variety of human types in an attempt to find what he considered to be basic primitive types, having remained outside the blending that had occurred across the ages (Vinson D., 2008). The presence of Bellonie Chantre played a key role, notably in obtaining women’s acceptance to be photographed. She is the one who contributed to the renown of this trip by publishing an account with Hachette in 1893.

The explorer increased the number of field expeditions to augment the number of observations and record an impressive volume of anthropometric data and photographic records that were to serve his project to describe and classify the Other (Vinson D., 2008). At the beginning of the 20th century, he turned his attention towards North Africa, where he applied this method during his anthropological research in East Africa, Egypt and Nubia, published in 1904. Finally, at the beginning of the decade of 1910, he set out accompanied by Dr Lucien Bertholon to explore Eastern Barbary, Tripolitania, Tunisia and Algeria. His earliest results were published in the Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie of Lyon and the Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris and thereafter in a two-volumes overview in 1912-1913.

Ernest Chantre and his wife, a faithful assistant whose literary aptitude he relied upon, are representative of these travelling-anthropologists around the turn of the 20th century, aiming to build an “ethnogenic” table of the populations of the globe based on ever expanding field studies in the colonial context. Thus, their anthropological studies fit within a dominant ideological framework whereby human groups were classified according to racial criteria. However, beyond the dry data of anthropometric measures, the accumulation of photographs and other observations allow one to perceive their sensitivity and their subjectivity. They also offer fascinating examples with which to approach the history of mentalities and representations during this period (Vinson D., 2008).

Institutional recognition

In parallel to his academic position and the many important missions of exploration involving an intense activity of publication, Chantre had also taken on a number of more ad hoc institutional responsibilities as well as roles in a great number of French and foreign scholarly societies. Despite a few enmities ̶ one of which was perhaps the “skull affair” over which he was in confrontation with his superior, Dr Louis Lortet ̶ his long career earned Ernest Chantre a high level of recognition in France and abroad (François M. et Ramousse R., 2007).

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

The collection

Ernest Chantre did not, strictly speaking, build a collection. The various sets of anthropological and naturalist specimens as well as the archaeological and ethnological objects that are currently kept in public collections in France are the fruit of collection drives, digs and purchases conducted over the course of his explorations across the national territory or abroad, at a time when the countries concerned had no legislation regarding the protection of heritage.

A few objects from Turkey, from the region of Urfa and from Birecik, were already registered in the Inventaire du Musée des Antiquités nationales in 1881 under the numbers 26,573 to 26,580.

In the publication he produced at the end of his mission to the Caucasus, the explorer provided a list of the objects specially gathered for the Muséum de Lyon during his trip (Chantre, 1881, p. 25 et suiv.). He also specified that in 1879, the owner of the terrain where the protohistoric necropolis of Koban (North Ossetia) excavated, with the help of foreign scholars, “over five hundred tombs which brought to light no less than twenty thousand objects. These are currently dispersed in several public or private collections of which the main ones are the Musée national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, colonel Olchewski in Vladikavkas, the Imperial Museum of Vienna, the Museum of Tiflis, Count Ouvaroff, the Muséum de Lyon, the History Museum of Moscow, general Komaroff in Tiflis and professor Virchow in Berlin” (Chantre E., 1881, p. 14).

Careful to make public his extraordinary results and research from Koban, Chantre ensured the swift publication of his entry into the pubic collections of France, in the Musée des Antiquités nationales de Saint-Germain-en-Laye (MAN) and the Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Lyon. An important part brought back to France –outside of any sharing agreement with the country of origin – was acquired by the MAN in November 1882 (n° 27110 to 27226 and 27258 to 27270), though already in March and in July of the same year, the master digger made a gift to the Museum of the majority of his findings (AN, F21/4443; AN, 20150539/101, 102). It is possible that owing to the onerous acquisition of November, the administration of Beaux-Arts wished to express its recognition of the archaeologist, who found it necessary to show the public of Western Europe the discoveries of an extraordinary quality as well as showing a previously unrecognised protohistoric civilisation. Finally, on 20 March 1883, other objects from Transcaucasia were registered, received by the intermediary of the new Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. Of all the numbers in the inventory attributed to archaeological material brought back from the Caucasus by Chantre and acquired by the Musée d’Archéologie nationale, 250 numbers refer to the materiel from the necropolis of Koban, for a total evaluated today at approximately 850 individualised objects. Undoubtedly twishing to be reimbursed for part of the 10,000 francs he used of his personal fortune, the archaeologist, in a letter dated 12 November 1882, reminded Alexandre Bertrand, director of the MAN, “that he [him] would be very agreeable to receiving by the end of this month [November] the greater share of the amount for the bronzes form Koban, as well as the fact he had had the generosity of offering it to himself (Lorre C., 2007; 2010). The bronze objects were, with a few terra cotta vases with geometric decorations, the essential part of the funerary furnishings gathered, from both male and female sepulchres. Amongst the most spectacular objects are a great number of harness elements or ornaments (bits, bit clips, belt plates, zoomorphic pendants, braided armbands, hammer-headed pins and bells) as well as weapons whose state of conservation indicated a more symbolic rather than real use (spearheads, arrowheads, daggers and axe blades).

This archaeological collection was the subject of another study under the framework of a doctoral thesis (Bedianashvili G., 2016). In parallel, all the furniture was gathered, photographed and recorded in a computer database with the aim of placing it online via Joconde, the national database.

This work was carried out with the Musée des Confluences (Lyon), the former musée Guimet-muséum d’histoirenaturelle, of which Chantre was the deputy director. It is the institution possessing the second important part of the full set of objects Chantre brought back from the Caucasus, now made available digitally because 350 objects come from the only female sepulchre studied, n° 9, which was studied and rebuilt in the context of the section “Éternities” of the new path of the visit through the permanent collections (Bodet C. et Mathieu J., 2014).

The Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (Paris), heir to a large part of the collections of the former Musée de l’Homme, contains at least 405 pieces from the explorations of Ernest Chantre. In addition to a few ethnographic objects, most are photographic documents brought back from the Caucasus, Anatolia and Egypt. According to the database accessible to the public, a few archaeological pieces also come from the necropolis of Khozan (Egypt), excavated by Chantre in 1899; these objects, from the pre- and proto-dynastic period, complete the main lot conserved in the Musée des Confluences de Lyon.

In the current state of research, several French museums possess a sampling of objects discovered in the ancient necropolis of Koban for which it is not always possible to ensure their link to the Lyonnais archaeologist. Thus, Claudine Jacquet demonstrated that he had sent in early 1882 a lot with some fifty objects to his friend Émile Cartailhac, on the occasion of the inauguration of thelaboratory of anthropology of Toulouse. It seems probable that these objects were incorporated into the collection of the musée Saint-Raymond when Cartailhac took over its direction in 1912 (Jacquet C., 2016). However, the circumstances of the acquisition of some fifty objects related to the discoveries made in Koban and recorded in the inventory of the Musée avoisien de Chambéry do not allow us to determine whether they come directly from Chantre’s discoveries (Cheishvili A., 2008). In 1881, another smaller set of ethnographic objects from Georgia and Turkey at first seem to have been donated by Chantre to the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (Paris) before being transferred to the musée d’ethnographie de l’université de Bordeaux in 1901 (Dupaigne B., comm. personnelle).

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Ernest Chantre's Travels

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne