DESOYE Louise and Emile (EN)

Biographical article

The ‘E. Desoye’ shop, located at 220, Rue de Rivoli in Paris, was considered legendary by the first practitioners of Japonisme, such as James Whistler (1834-1903), Edmond (1822-1896) and Jules (1830-1870) de Goncourt, and James Tissot (1836-1902), who described this shop as being the first in France to specialise in objects directly imported from Japan and as a ‘school’ for those who were interested in Japan (Goncourt, de E., and Goncourt, de J., 1989, 31 March 1875). Initially selling garments, books, and lacquered objects that were brought back from a trip to Japan, the Desoyes subsequently imported all sorts of objects (ivories, enamels, weaponry, figurines, and screens) that they sold to ‘Tout Paris’ (Emery, E., 2020), the upper crust of Parisian society. Their customers included writers and artists, such as Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and his brother William (1829-1919), Laurent Bouvier (1840-1901), and Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), and collectors such as Auguste Lesouëf (1829-1906), Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877), and Clémence d’Ennery (1823-1898). The Desoyes’ shop at 220, Rue de Rivoli, which specialised in Japanese curios, must not be confused with other curiosity shops (‘A la Porte chinoise’ and ‘La Jonque chinoise’), as is often the case.

Little is known about the Desoye couple’s life before their marriage on 28 April 1863, the year in which the name of their shop, E. Desoye, appeared for the first time in the Bottin (a yearbook of commerce and industry named after the French administrator Sébastien Bottin, (1764-1853). Monsieur Desoye was described as a person of independent means on the marriage certificate, lived between Port-à-l’Anglais and Rue de Rivoli in Paris (Archives départmentales du Val-de-Marne, AD 94), 1MI/1032). Their marriage contract describes him as a ‘merchant’ and states that their business assets from the sale of ‘objects of curiosity’ amounted to 80,000 francs (AN, MC/ET/RE/II/1127). The son of Pierre Joseph De Soÿe, a coachman of Dutch origin, and Marie Catherine Latine, a dressmaker, Jean Baptiste Desoye was born in Brussels on 2 November 1811 (AEB, civil registry, 1811, 2462) and died at his home on 7 January 1870, at 220, Rue de Rivoli (AP, V4E00098). In 1844, at the time of his sister’s marriage, he worked as a maître d'hôtel in Brussels (AEB, marriage certificate, 1844, 116). Nothing else is known about his life between 1844 and 1862, apart from a sojourn in Japan prior to 1862 (L. R., 1863).

The daughter of a single mother (Marie Barbe Richard) and a father, Joseph Chopin, who recognised her as his daughter in 1837, Louise Mélina Chopin was born in Mangiennes (in the Meuse département) on 20 April 1836 (AD 55, 2E324 9). Her parents died in 1840 and 1841 respectively. Described in her marriage contract with Jean Baptise Desoye (AN, MC/ET/RE/II/1127) as a partner in their business, she seems to have taken over the management of the shop while her husband was incapacited by a long illness (AN, MC/ET/RE/II/1167). This may explain why ‘Mme Desoye’ was often described as the owner even while her husband was alive. The ‘Veuve Desoye’ shop at 220, Rue de Rivoli appeared in the Bottin until 1888.

In 1874, Louise Desoye married Joseph Auguste (‘Maurice’) Lasmolles, who worked for a maritime insurance company ; the marriage contract specifically allowed her to continue running the business (AN, MC/ET/II/1184). The couple moved to Asnières, where they lived in the house acquired by the Desoye couple in 1869 just before Jean Baptiste’s death. Louise Desoye Lasmolles had three children: a daughter, Berthe Gabrielle Desoye, born on 15 August 1867 (AP, V4E 67), a second daughter, Louise Céline Lasmolles, born on 29 December 1874 (AP, V4E 2513), and a son, Maurice Gaston Lasmolles, born in Asnières on 7 September 1876 (AD 92, ASN109).

Records show that the Desoyes went to Asia prior to 1863 (L. R., 1863; Burty, P., 1877; Rossetti W. 1903), but there are currently no tangible traces of their activities in Japan. Their first customers, such as Philippe Burty (1830-1890), spoke of a sojourn in Japan and their knowledge of the Japanese language and culture (Burty, P., 1877; and Burty, P., 1880). Furthermore, a letter sent by Mme Desoye to Edmond de Goncourt in 1884 describes her as the ‘leading importer of fine [Japanese] objects’ (BNF, N.A.F. 22460, folios 302 à 303r). Indeed, although the Desoyes actively participated in the sale and exhibitions of Japanese-style objects in the 1860s, it was Madame Desoye who was considered an ‘expert’ by customers such as Burty and Rossetti. In fact, it was she who explained the significance of the Japanese albums to the customers, told them stories, taught them how to pronounce Japanese words, and put them in touch with other enthusiasts of Japanese objects (Burty, P., 1877; Rossetti, W., 1903; and Emery, E., 2020).

The collection

One of Madame Desoye’s grandsons remembered a ‘Chinese-style house’, built in his grandmother’s garden in Asnières, where she kept armour, weaponry, vases, and other precious Asiatic objects. It appears that some of these objects came into the possession of her daughter, Louise Céline. Indeed, her Parisian apartment was so full of Japanese and Chinese objects that her grandchildren felt they were in Asia. Unfortunately, the collection was dispersed after her death in 1942 (Emery, E., and Huet, M., 2019, n.p.).

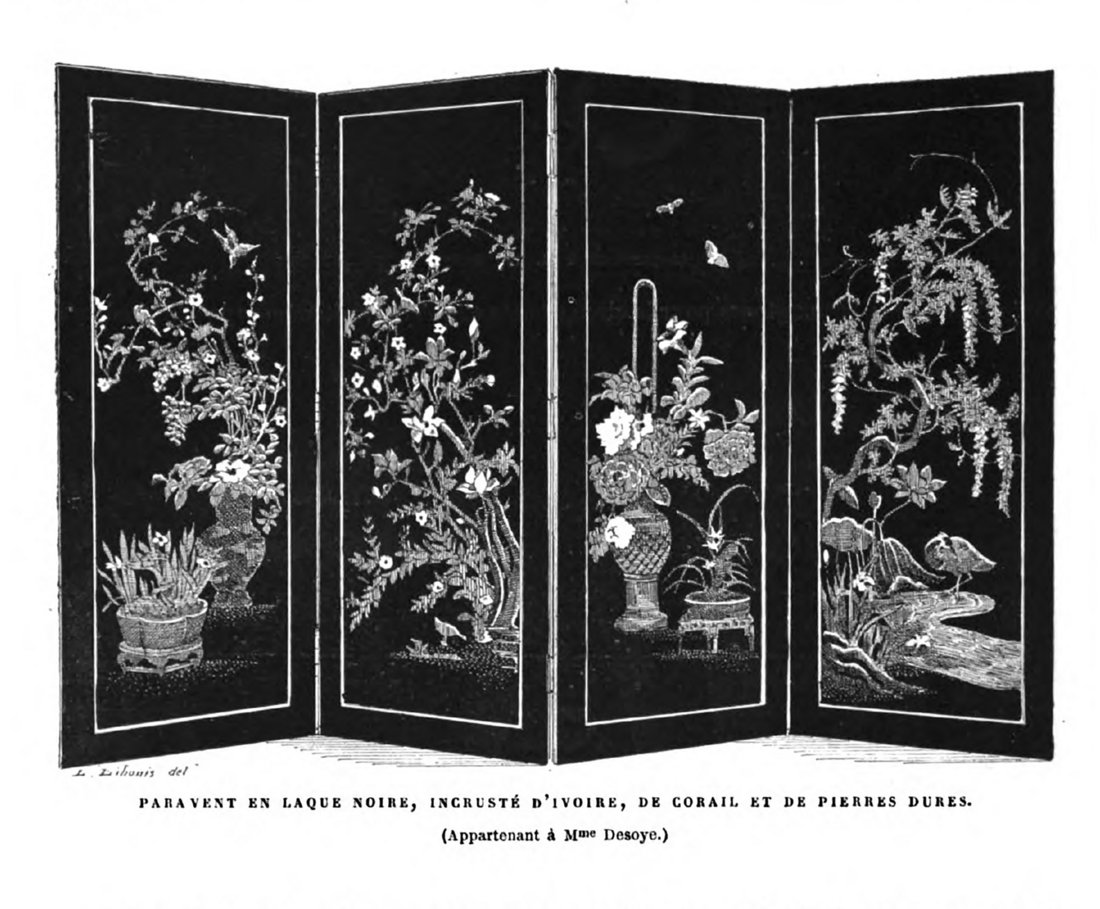

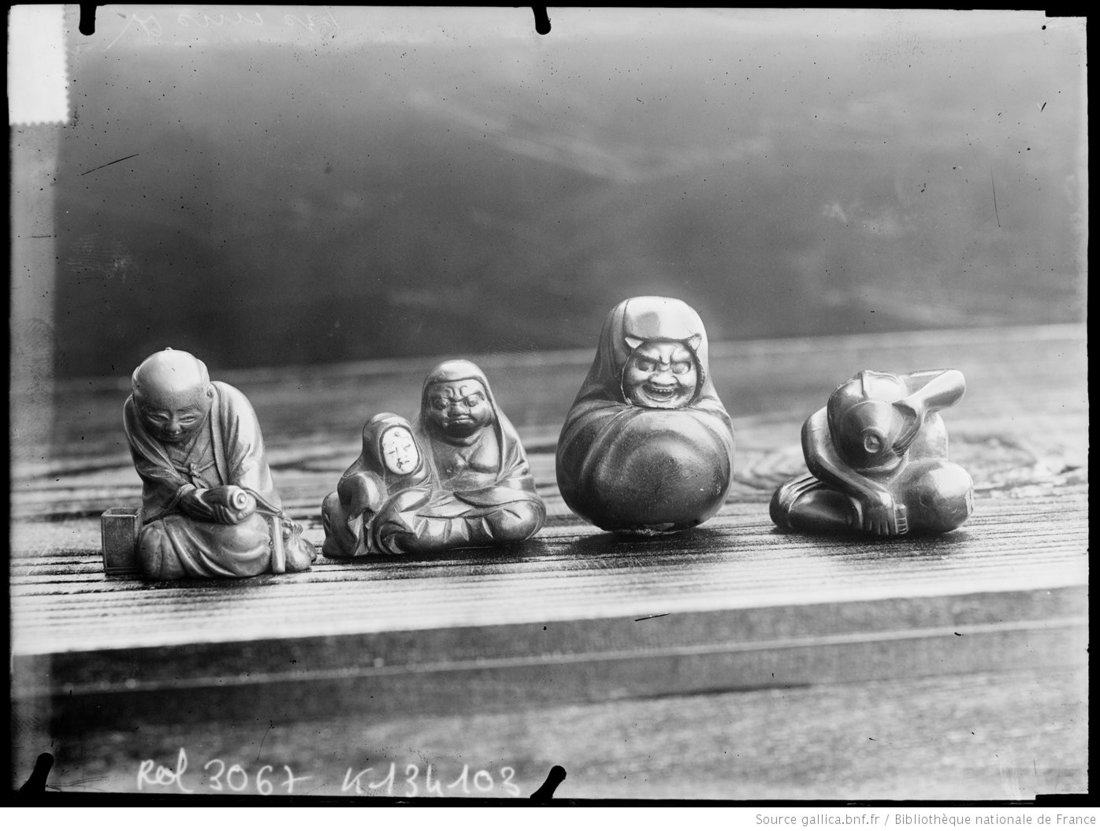

Judging by articles, auctioneers’ records, and their customers’ recollections dating from the 1860s, the Desoyes were the first Parisians to describe themselves as specialists in Japanese objects, and their target customers were artists and tourists (L.R., 1863; Rossetti, W., 1903; Emery 2020). This specialisation was indicated on the labels and invoices, and repeated in the advertisements, like those of the Guide de l’étranger à l’Exposition de 1867 (Emery, E., 2020). They allegedly returned from Japan in 1862 with a ‘fine collection of weaponry, fabrics, paintings, and objects of all kinds’ that they exhibited to the public (L.R., 1863, p. 217). By acquiring Japanese objects in Parisian auctions—lacquered objects, ivory caskets, garments, and figurines—originating from collections assembled by travellers and military men who had lived in China (like Eugène Louïrette’s collection in 1864), they were able to increase their stock.

In 1883, Madame Desoye was described as a forerunner—‘the providence of early Japonistes’—thanks to the prints, garments, furniture, and the various small objects she sold in her shop (Josse, 1882, p. 33; and Burty, P., 1880, p. 144). Her collection no longer exists but we have only to look at the ‘Japanese-inspired’ paintings by James Whistler, James Tissot, and Jean-Georges Vibert (1840-1902), painted in the 1860s and 1870s, to see objects that were sold in her shop. As stated by Burty (1880), Josse (1882), and Goncourt (Goncourt, de E., and Goncourt, de J., 1989, 31 March 1875), her greatest legacy was being one of the first ‘to teach’ her customers, to hold events to explain the cultural and artistic importance of the objects for sale, before Japonisme became a mass phenomenon. Burty, for example, stated that it was she who informed him about ‘a series of small objects ornamented with very curious engravings on wood’ (L’Histoire des chiens célèbres), which he bought in her shop (Burty, P., 1872, p. 60); and Edmond de Goncourt referred to her as ‘An almost historic figure of the time, because the shop was the place and the school, so to speak, where this major Japanese-inspired movement developed, which has now influenced everything from painting to fashion’ (Goncourt, de E., and Goncourt, de J., 1989, 31 March 1875). She was, in fact, as she herself wrote in a letter to Edmond de Goncourt (BNF, N.A.F. 22460), the 'leading importer' of specifically Japanese objects, as of the 1860s.

Related articles

Personne / collectivité

Personne / personne

Personne / personne