MONET Claude (EN)

Biographical article

Born in Paris on 14 November 1840, Claude Monet—called Oscar-Claude by his parents—was the second son of Adolphe Monet (1800–1871) and Louise-Justine Aubrée (1805–1857). The family moved to Le Havre circa 1845 and Claude attended school at the Collège Municipal, where the drawing classes were taught by François-Charles Ochard (1800–1870), a former pupil of David (1748–1825). Eugène Boudin (1824–1898), his first mentor, whom he met circa 1858, gave him the chance to produce studies after nature, working with a paintbrush and pastels. In 1859, he went to Paris, attended the Académie Suisse the following year, then the Académie Gleyre between 1862 and spring 1863, where he struck up a friendship with Frédéric Bazille (1841–1870) and Auguste Renoir (1841–1919). He painted his first motifs on the Norman coast in the company of Bazille and then at Honfleur with Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819–1891). He exhibited his work for the first time—and with success—at the 1865 Salon and began work on the picture Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Musée d’Orsay, Paris, inv. no. RF 1668), which was praised by Gustave Courbet (1819–1877); he left this work unfinished.

The years 1866–1867 were marked by encounters, perhaps at the Café Guerbois, frequented by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), Félix Bracquemond (1833–1914), Philippe Burty (1830–1890), and Émile Zola (1840–1902); he met Édouard Manet (1833–1883), who supported him and helped him financially. Zola congratulated him for his work Camille en robe verte (Kunsthalle, Bremen, inv. nos. 298–1906/1) which was a great success at the 1866 Salon. The common denominator of all these figures was their great interest in Japanese prints, which had recently been discovered in France. There was many a heated discussion about japonaiseries, during which the name of Hokusai (北斎) (1760–1849) was often brought up, in particular for his small volumes of ‘Mangwa’ that moved from studio to studio.

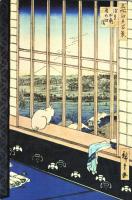

At the same time, between 1866 and 1869, the painter’s style developed as he abandoned the traditional academic approach. His views of the Louvre in 1867 viewed from the Colonnade—Le Quai du Louvre (Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, inv. no. 0332453), Le Jardin de l’Infante (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, inv. no. 1948.296), and Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois (New National Gallery, Berlin, inv. no. A I 984)—attest to a new form of optics, comparable to wide-angle photography. The plunging view, resembling that of the ukiyo-e draughtsmen, opened up the landscape. The Albertian perspective with atmospheric effects was replaced by aerial perspective. The pictures painted in Normandy—La Terrasse à Sainte-Adresse (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no. 67.241) and La Cabane à Sainte-Adresse—explicitly refer to two prints from Hokusai’sseries of ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’. The first evoked The SazaiPavilion atthe Temple of the Five Hundred Rakan, in which the koinobori (a carp-shaped kite) frame the scene, just as flags provide balance in Monet’s work; the second, Cabane à Sainte-Adresse, in which the scene is viewed from below and with its cabin and thatched roof facing the sea, is reminiscent of Lake Suwa in the Province of Shinano.

This new interpretation of space, with, in particular, the foreground cut by the frame (La Grenouillère) or an unusual viewing angle—a plunging view sometimes combined with a view from below (Les Déchargeurs de Charbon)—was now the mark of an Impressionist Monet influenced by a Far-Eastern aesthetic.

Having sought refuge in London between 1870 and 1871, he met up with Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and met James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903); and, after returning to France—via Holland (Zaandam)—, Monet participated in 1874 in the Parisian exhibition of the ‘Société Anonyme Coopérative d’Artistes’, known as the ‘Première Exposition des Peintres Impressionnistes’, along with Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Giuseppe de Nittis (1846–1884), and Félix Bracquemond, to mention just a few of the artists who were amongst the first connoisseurs of Japanese art. Monet presented a landscape entitled Port du Havre, generally known as Impression, Soleil Levant (the Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris, inv. no. 4014). During a second exhibition he presented the picture Japonerie, now known asLa Japonaise (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. no. 56.147), a portrait of his girlfriend Camille dressed in the splendid robe of a Japanese actor, with a blond wig, posing in front of a wall decorated with Japanese fans. This was a humoristic nod to ‘japoniaiserie’, to borrow the expression of Chamfleury (1821–1889). The picture was sold at the Hôtel Drouot the following year with its original title.

In 1883, he moved to Giverny with his two children and Alice Hoschedé (1844–1911) and her family. He bought the property in 1890, and set up the garden, greenhouse, and a new studio; in 1893, he purchased marshy land further down from the house and traversed by the Epte River. This area became the water garden surmounted by a Japanese bridge, then after being dug out—and over the years—turned into the world-famous basin with water lilies. In this constantly changing setting the collection of Japanese prints was continually enriched. An incontestable source of inspiration, it was also a source of ‘after-images’, as in Rochers à Port-Coton (Belle-Île), produced in 1886, undeniable evoking the seascapes of Hiroshige and Hokusai. In the wake of these different versions, which foreshadowed the serial works, the series of the ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ were produced by Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重) (1797–1858) and, above all, the series by Hokusai. The latter depicted Mount Fuji from various geographical viewpoints, appearing in the foreground or background. The atmospheric elements, such as Sudden Storm Below the Summit or Fine Wind, Clear Weather, also known as RedFuji, echoed Monet’s own quest.

While the Japanese ‘series’ triggered series such as the Meules, Les Peupliers, the Cathédrales painted in Rouen, and even the Nymphéas of 1909, they were distinguished by Monet’s obsession with painting a single motif in different seasons, hours, and lighting.

Immersed on a daily basis in his Japanese images, he was imbued with a sense of nature that was shared by the ukiyo-e draughtsmen, by excluding the element of intellectualism characteristic of Western landscapes since the Renaissance. He was the only artist amongst the Impressionists to doggedly follow this path. During his stay in Norway in February 1895, he wrote to Alice: ‘(…) it is like Japan, which is often the case in this country. I have before me a view of Sandviken, which looks like a Japanese village; then I paint a mountain that can be seen here from every vantage point and which reminds me of Fuji-Yama’ (W.III letter no. 1276, p. 282).

Water lilies invaded the canvases as of 1914, ranging from the simple format of easel paintings—like the image of the basin with water lilies— to the representations of the small and large basins at Giverny. This conception of a decorative ensemble may be associated with a Japanese painting, The Crane Room at Nishi Hongan-jiinKyoto, a copy of which was exhibited at the 1910 Anglo-Japanese Exhibition in London. It is adorned with a decor featuring flying cranes and wallpaper with motifs of chrysanthemums. Given to Émile Guimet (1836–1918), it was exhibited in the eponymous museum in Lyon (currently held in the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, inv. nos. MGL1, and MGL597 to 674). The journal L’Illustration reproduced it in 1910 and many articles were published in the French press.

One might imagine Monet’s curiosity and interest in such a work; he substituted the flying cranes with these cultivars which had recently been introduced to France. ‘Plants on a ground of bluish water act like a gold ground, plants that the hand of man has not assembled in a bouquet, but rather huge plants, larger than life—plants that are not arranged in a traditional manner and which seemed to extend beyond the boundaries’ (Dorival, B., 1977, p. 48).

Interested in this symphony of water, flowers, and grass, Claude Monet transmitted his own vision to the viewer: the indescribable union of man and nature, as he perceived it through art and Far-Eastern culture. As he declared to Claude Roger-Marx (1888–1977) who came to interview him in 1909: ‘If you must (…) affiliate me with something, then liken me to the ancient Japanese: I have always admired the rarity of their taste and I approve of their aesthetic choices, which evoke presence through shadows, and the ensemble through fragments’ (June 1909, pp. 523–531).

The collection

Thanks to Michel Monet’s donation to the Musée Marmottan-Monet, (no commentary), Claude Monet’s collection of Japanese prints, one of the rare ones to have survived—if not entirely then at least in its unity—was placed in its original setting, when his residence in Giverny was reopened in 1980.

Post-death inventory

After the artist’s death, a brief inventory was drawn up by Maître Legendre on 14 January 1927. He counted the number of frames, rather than the number of prints (as a frame might house several woodblock prints), followed by the presentation area and the estimated price. Hence: ‘Fifty-one Chinese and Japanese prints’ kept ‘in the studio near the entrance door’, for 1,256 francs; ‘Thirteen Chinese and Japanese prints’, kept ‘in the hallway’, for 330 francs; ‘Forty-nine Japanese prints in the small salon’ for 2,500 francs; and, lastly, ‘fifty-nine prints in the dining room’ for 1,300 francs; that is to say a total of 172 items, with a total value of 5,386 francs.

At the Michel Monet bequest, the valuation was drawn up per article and in a detailed manner by taking into account decorative objects and frames (by applying the previously used process). There was a total of 219 items, without including a cardboard box and a lot of unspecified prints, as well as ‘softcover volumes’.

The collection at Giverny currently comprises 230 items (simple sheets, triptychs—some of which are incomplete—, and diptychs are counted as one article). The Japanese library, held in the Musée Marmottan, houses thirty-six small-format albums that may be dated between 1795, with Ryakugashiki by Kitao Masayoshi (北尾政美, 1764–1824), and 1864, with the volume of the EhonEdo Miyage, Illustrated Book: Souvenir of Edo by Hiroshige. The name Hokusai is mentioned twenty-two times and comprises twelve of the fifteen volumes of the Mangwa.

The Japanese print as decor

Old photos of the dining room and the blue—or purple—salon, depending on the era, show the cosey decor of the country house, whose walls were decorated with ukiyo-e prints. The latter also adorned the hallway, the stairway leading to the bedrooms of Alice Hoschedé and Monet, and even the cabinets de toilette.

This environment has convincingly and realistically reflected the passion of an artist and his era, many years after the craze for Japanese art had vanished. Monet was not the only artist to collect the ukiyo-e, but this exceptional ensemble is one of the only collections that visitors can still see as it existed—or almost—in the artist’s daily life. This rarity accounts for its tremendous historical interest. Giverny enables visitors to embark on a marvellous journey back in time to discover what a Japanese collection truly looked like in the life of an Impressionist artist.

An analysis of the collection

This collection can be viewed in two ways: on the one hand, the prints selected by the artist based on pictorial criteria reflect the artist’s love of colours and lines; and on the other, it is an ensemble collected by a lover of Japanese curiosities who was well advised by connoisseurs and dealers, which accounts for the quality of the prints, the printing, and the state of conservation. This resulted in a varied collection that comprised famous works such as Make-Up by Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿) (1753–1806), Under the Wave off Kanagawaby Hokusai (1760–1849), and Great Bridge:Sudden Rain at Atake (Ohashi)by Hiroshige (1797–1858).

The three major and well-known engravers of these ‘images of passing time’—Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige—account for more than half of the collection.

Attracted by the elegance of the eighteenth-century courtesans of Torii Kiyonaga (鳥居清長) (1752–1815) and Utamaro, Monet seemed to be less fascinated by the graceful figures of Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春) (1724–1829), represented by two prints: no. 4 and no. 5. Out of preference and influenced by the shop owners, he collected, like the japonisants, triptychs by Chōbunsai Eishi (鳥文斎栄之) (1756–1829) and Utagawa Toyokuni (歌川豊国) (1769–1825), whose colours have unfortunately faded. Less famous than their master Eishi, Rekisentei Eiri (礫川亭永理, 永理) (active in the 1790s) and Chōkōsai Eishō (鳥高斎栄昌) (active in the 1790s) represented, for the former, a winter scene—The Three Visits—, and, for the latter, the famous A Bust Portrait of Kokin. Tōshūsai Sharaku (東洲斎写楽) (active in 1794–1795), whose work was very rare, was represented by three portraits of actors immortalised on a micaceous black and white ground: no. 56, no. 57, and no. 58.

The nineteenth century was represented, initially, by Hokusai, all of whose works were very refreshing, in particular Kajikazawa in the Province of Kai and Snow on the Sumida River. The landscapes executed in the environs of Edo by Utagawa Kunisada (歌川国貞) (1786–1865) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (1798–1861) attracted the painter’s attention. At the end of the nineteenth century, at the Expositions Universelles, Westerners initially discovered Yokohama’s engravings, which aroused much enthusiasm for this marvellous world amongst Monet and his contemporaries. Subject matter comprising war scenes emerged (Sino-Japanese, 1894–1895, then Russo-Japanese, 1904–1905) and the representation of foreigners in Japan captured in scenes from real life, using bright aniline colours, sometimes seen as brash by Westerners.

This highly eclectic ensemble provides an almost complete panorama of the ukiyo-e production from the 1750s until 1870, with the exception of the primitive black and white prints and (erotic) shunga, absent from the painter’s collection. The core of his collection consisted of themes that reflected the artist’s tastes: landscapes, and the fauna and flora of Hokusai and Hiroshige. The former was represented by twenty-two plates, nine of which came from the famous series of the ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ (nos. 59 to 67), and three from the series of large flowers (nos. 68 to 70). Monet wrote about this to Maurice Joyant (1864–1930): ‘I would like to thank you for thinking of me with regard to Hokusai’s flowers (…). You are not talking about the poppies, and that’s important, as I already have the irises, chrysanthemums, peonies, and morning glories’ (W. letter 1322). As for Hiroshige, Monet purchased fifty plates extracted in particular from the series of the ‘Fifty-Three Stations on the Tokaido Road’ (nos. 114 to 116, and nos. 136–137), Views of Edo (nos. 124 to 127, no. 132), and ‘Sixty-Odd Provinces’ (nos. 138 to 148), as well as kakemono featuring cranes (nos. 133–134) and prints from the series of ‘Fish’ (nos. 120 to 123).

The discovery of Japanese prints: a well-nurtured myth

Monet claimed that he discovered his first Japanese prints at the age of sixteen in 1856 in Le Havre, in a shop ‘where one looked through the curiosities brought back by long-haul ships’ (Elder, M., 1924, pp. 63–64). But, questioned about this by Gustave Geffroy (1855–1926), his biographer, Monet accredited the idea that he discovered Japanese prints in Holland (Zaandam) in 1871. And his friend Octave Mirbeau (1848–1917) expanded on this version: ‘I often thought, on this trip, about the magical day when Claude Monet, having come to Holland, around fifty years ago to paint there, found a brochure, a packet, the first ever Japanese prints that he set eyes upon (…). When he came home, Monet delightedly spread out “his images”. Amongst the finest of these, the rarest prints, he was unaware that they were works by Hokusai and Utamaro (…). This was the beginning of a famous collection (…)’ (Mirbeau, O., 1977, pp. 219–220). Wherever he first saw Japanese prints by Hiroshige or Hokusai—in Le Havre, Paris, Zaandam, Amsterdam, or London—, he remained faithful to these images throughout his long life.

Siegfried Bing and Hayashi Tadamasa: dealers, collectors and advocates of the new form of painting

In his Journal, Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896) recounted on 17 February 1892 that ‘I often come across Monet at Siegfried Bing’s (1838–1905), in the small attic with the Japanese prints’. In 1878, Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) opened a shop of Japanese art at 19, Rue Chauchat in Paris, listed in the Annuaire du Commerce under the heading ‘curiosités’. This place, as attested by the writer, became a veritable place for social gatherings for artists and writers. Aside from Monet, Henri Rivière (1864–1951) also used to visit Bing’s attic; and it was here too that Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), during his stay in Paris between March 1886 and February 1888, admired Japanese albums and prints.

Monet met Hayashi Tadamasa (林忠正) (1853–1906), who came to France as an interpreter at the 1878 Exposition Universelle; and exchanges were made with the collector of Western art: pictures ‘for prints. Fifteen extremely rare prints acquired by the artist bear the cachet of Hayashi and that of Wakai Kenzaburo (若井兼三郎) (1834–1908), with whom Hayashi worked until 1889; some of Eishi’s triptychs and the fine Utamaros and Hokusais collected by Monet came from Hayashi. The latter was regularly solicited by connoisseurs of Japanese art to find the rarest objects, to inform them about the traditions and customs of the Japanese, decipher the meaning of the images of the ukiyo-e, and translate it for these neophytes. The works of Louis Gonse (1846–1921) about L’Art japonais (1883) or by Edmond de Goncourt on Outamaro (1891) and Hokousai (1896) and the collections owned by Monet and de Rivière would never have existed without his learning. Their richness and quality, as well as their great familiarity with Japanese woodblock prints are indebted to this discreet man who was devoted to their art.

An insight into Monet’s Japan-inspired culture

Although he was living in the countryside, Monet kept track of Parisian events, as evident in this letter sent to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922): ‘The Japanese exhibition is not opening on Tuesday [the retrospective of Japanese Art held by Louis Gonse in 1883 in the Galerie Georges Petit] but tomorrow, Monday. So, I will come tomorrow’ (W. letter 339, dated 8 March 1883, Villa Saint-Louis, Poissy). And in 1893, Camille Pissarro told his son Lucien (1863–1944) that he had been to see the exhibition ‘Estampes d’Outamaro et de Hiroshighé’ (‘Prints by Utamaro and Hiroshige’), held by Bing in the Galerie Durand-Ruel: ‘An admirable Japanese exhibition. Hiroshige is a wonderful Impressionist. I, Monet, and Rodin love his work (…) these Japanese artists confirm our visual approach’ (Pissarro, C., 1950, p. 298).

Monet’s library in Giverny now houses several books on Japan dedicated to the painter: Critique d’Avant-Garde (1885) by Théodore Duret (1838–1927), in which a chapter is devoted to Hokusai, Essai sur le génie japonais (1918) by Henri Focillon (1881–1943), and Au Japon, promenades aux sanctuaires de l’art (1908) by Gustave Migeon (1861–1930). Studies on Hokusai dating from 1896, signed by Michel Revon (1867–1943), Edmond de Goncourt, and Siegfried Bing for La Revue Blanche highlight the fashion for Hokusai and the painter’s preference for the engraver’s work.

Conclusion

A famous photograph (Piguet Collection, Giverny) shows Monet sitting proudly in the middle of the dining room. Here, he invited his friends Gustave Geffroy, Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929), and Octave Mirbeau (1848–1917); Japanese prints were an essential element in this room for social gatherings. Another photograph shows Monet showing his garden to the collector and shipowner Matsukata Kōjirō (松方幸次郎) (1865–1950) and his niece, Princess Kuroki.

Monet’s basin, with its reflections, water lilies, and Japanese bridge, was the paradigmatic example of this immersion in the world of Japan. From the prints to the garden, from the interior to the exterior, from the two-dimensionality of art to the three-dimensionality of nature, the immersion in all things Japan was no longer simply visual, but extended to everything, from the living areas to the pictorial space.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne