BEURDELEY (EN)

Family History: From Dealers to Collectors

Originally from Burgundy but established in Paris, on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Jean Beurdeley (1771-1853) founded a shop selling curiosities around 1817, which was taken over and run by his son Louis-Auguste-Alfred Beurdeley (1808-1882), then his grandson Alfred-Emmanuel-Louis Beurdeley (1847-1919). From the outset, Jean was associated with trade in furniture and second-hand goods, but it was his son Alfred Beurdeley (known as “Beurdeley père”) who considerably developed their activity.

Under the Second Empire, Beurdeley père became one of the most important dealers in curiosities and works of art in the capital. Under the July Monarchy, his shop was moved to the Pavillon de Hanovre, at the corner of Boulevard des Italiens, in a building acquired by the family in 1830. The store was thus located in the heart of chic Paris at the time and there one could find a quantity of varied and precious goods: marble statuary, ivories, glassware, antique jewellery, bronze clocks, paintings, chandeliers, furniture in marquetry or lacquer decoration, hard stones, antique jewellery, Sèvres porcelain, and porcelain from China and Japan, both mounted and unmounted. From the middle of the century, Beurdeley père added to the antique trade the design of modern objects in the style of the Renaissance and the 18th century. As such, he participated in the great universal exhibitions, in 1855 and then in 1867, where he won a gold medal. After a law degree, his son, Alfred-Emmanuel-Louis (known as “Beurdeley Fils”), took over the family business in 1875. He undertook the construction of a workshop for the manufacture of "bronzes and furniture" in the Epinettes district, on the rue Dautancourt. He therefore jointly carried out the activities of dealer in curiosities and manufacturer of furniture and works of art. His participation in major exhibitions was noticed in Paris in 1878, in 1889, and even in Chicago in 1893, which enabled him to win over an American clientele. Despite this transatlantic expansion, he closed the house in 1895. From then on, he devoted himself to his personal collection of drawings, engravings and works of art, mainly Chinese porcelain. It was moreover as a collector, in the midst of his boxes of drawings and prints, that he was portrayed by the Swedish Anders Zorn (1860-1920; 1907 Salon; Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 1979 48).

The borders are sometimes blurred between the business and the personal assets of the Beurdeleys, the practices of the collection and the profession being completely intertwined. The status of “collector” in fact signified the success of the dealer and the elevation of his social status — an ascent testifying to a new value system regarding old objectsthat gradually established itself over the century, in which an increasing number of goods become collectibles. This system was based on knowledge and expertise, and dealers played a key role in it. Throughout their careers, the Beurdeleys fulfilled a dual role of merchant and collector with museums and exhibition committees, a position that was not unique at the time if we think of Frédéric Spitzer (1815-1890), whose boutique home was referred to as the “Musée Spitzer” (Cordera, 2015), or ofthe expert-dealer Charles Mannheim (1833-1910). These dealers also benefitted from the various retrospective exhibitions that proliferated, particularly under the auspices of the Union centrale (created in 1863). In 1862, Alfred Beurdeley had his portrait painted by Paul Baudry (1828-1886), which is now in the Musée d'Orsay (inv. no. RF 1979 47). The choice of a painter who had won the Grand Prix de Rome was a testimony to his social and financial success. Two years earlier, he moved with his wife Virginie Fleytas (1804-1861), a wealthy aristocrat from New Orleans, into the private mansion at 79 rue de Clichy which was to house his collections and then those of Alfred Beurdeley Fils. The latter kept the family home, but put his father's collections up for auction, which led to two major sales in 1883. The history of this dynasty of Parisian merchants is also punctuated by numerous auctions, which, in addition to notarised acts, make it possible to understand both the contents of the business, their areas of expertise, and their personal collections. After the shop closed in 1895, sales of all wares "made Beurdeley's name legendary at the Hôtel Drouot, where it was on display for so many years", reports Marcel Nicolle (1920, p. 7). Conversely, it was also in the auction rooms that collections were formed, as testified by his friend Léonce Bénédite: "Beurdeley is present at all sales, without disdaining even the most modest ones, because he knows that it is where he will find the unexpected piece" (1920). As an art dealer, he had developed an eye and was accustomed to market practices. He was therefore well-prepared to develop collections.

Collections of Chinese and Japanese Porcelain from a Curiosities Dealer

Following a tradition that goes back at least to the 17th century, Chinese and Japanese porcelains were collected as objects of luxury, curiosities, and decoration, as were the silks and lacquers that the marchands merciersbought from European import companies. This tradition was continued by 19th century curio dealers, such as the Beurdeleys, and Oriental porcelain formed a large part of their stock. The most sought-after pieces at the time were decorative and evocative of 18th century taste, such as the large covered jars. Most of the Beurdeley's stock was made up of pieces acquired on the Parisian art market and originally designed for export, even if they were of old manufacture. From the first mentions of the stock, in the years 1830-1840, there were porcelains from China or Japan, for the most part associated with bronze mounts. As Jules Labarte wrote in 1847, it was still difficult for aficionados to differentiate Chinese and Japanese porcelain. It was not until the second half of the century that an understanding of Chinese art developed. From the 1860s, oriental ceramics gradually became objects of study, following the entry of Asian porcelain collections into museums and Albert Jacquemart's attempt at classification (1862). The sack of the Summer Palace in Beijing prompted many pieces of historical importance to enter Europe, triggering a specific market for Chinese art objects in Paris from 1861. It was also at the end of the 1860s that the Bottin du commerce de Paris dedicated a section to "Chinoiseries and Japoneries". Although he was not listed there as a specialist dealer, Alfred Beurdeley père’s stock also increased in this realmover the decade. As shown by a recent study, the latter was among the 20 principal buyers of objects of imperial provenance in sales of Asian works of art between 1861 and 1863 (Howald C., Saint-Raymond L., 2018, p. 14-15); his role, however, was relatively weak compared to that of other dealers, such as M. and Mme Malinet, for example (Nicolas Joseph Malinet, 1805-1886, and Marie Antoinette Malinet née Schlotterer, 1812-1881).

If we compare the wares of his shop from the 1860s until its closing in 1895, it is clear that the quantity of oriental porcelains and their proportional value increased during the second half of the century (Mestdagh C., 2019). The share of porcelain, all sources combined, remained stable and fluctuated around 15% of the total value of the store's stock. On the other hand, while porcelains from China and Japan represented 37% of the total value of porcelains in the 1870s (compared to 51% for Sèvres porcelains), they had risen to more than 55% by the end of the century. From 1886, Alfred Beurdeley Fils also enjoyed a situation that may have simplified the supply of Chinese porcelain since the dealers Myrtille and Isaë Oppenheimer, specialising in "articles from China and Japan", settled in rue de Cléry, but also in Hong Kong and Kobe, were tenants of part of the building of the Beurdeley ateliers on rue Dautancourt where they store a large stock of porcelain.

Mounted and Unmounted Porcelains

The tradition of mounted porcelains was inherited from the marchands merciers who specialised in this type of embellishment through association with Parisian bronziersfrom the time of Louis XIV (Castelluccio S., 2014). From the 1840s to the 1860s, almost all the Chinese porcelain in the shop was mounted, as candelabras, lamps, decorative vases, cups, or planters which were embellished with bronze mounts. At the time, the value of porcelain was generally considered to be increased by mounting, but during the 19th century this was tempered. Gradually, the increased interest shown by collectors and intellectuals explains why oriental porcelains were no longer systematically mounted. Thus, the sale of the Alfred Beurdeley collection in 1883 (Hôtel Drouot 23-25 April) lists a small section of ancient Chinese and Japanese porcelain comprising six large "famille verte" vases and numerous figurines, a total of 30 pieces of which only three were mounted, described as "Louis XV period".

A personal notebook of Alfred Beurdeley Fils, dating from the 1870s (private collection), shows a large number of hand-drawn pencil sketches: drawings of unmounted Asian porcelain and Sèvres porcelain, accompanied by coded prices, probably objects bought while traveling or which were offered to him. This notebook shows how Beurdeley Fils mixed his interests in oriental porcelain and the Sèvres porcelain that also constituted an important part of his stock. During the sales that followed the shop’s closing in 1895, a section was devoted to oriental porcelain, within the objects of art and furniture of the 18th century, described as "ancient porcelain", half of which was mounted (Galerie G. Petit, May 27 -June 1, 1895). Two subsequent sales were entirely devoted to "Chinese and Japanese porcelain", composed of vases and other unmounted porcelain pieces (Hôtel Drouot, March 24-25 and December 17, 1898).

Celadons mounted in gilded bronze were still highly sought after, a preference which demonstrates the resilience of the taste for the 18th century. In accordance with this taste and in the continuity of a Parisian tradition, the Beurdeleys created modern gilt bronze mounts for Asian porcelain of ancient quality. Alfred Beurdeley Fils developed his own workshop, but before that, his father already subcontracted many craftsmen: bronziers, carvers, and gilders, to produce various objects and in particular mounted vases (Mestdagh C., 2020, p. 172, fig. 1). Certain drawings in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs also document this practice and show projects for mounted vases in Chinese porcelain (CD 3062). The sale of works from the studio of Alfred Beurdeley Fils, following the closure of the company, opened with around 20 vases mounted in "Chinese porcelain of ancient quality" (Galerie G. Petit, May 6-9 1895). Knowing old porcelain from his activity and conscientious of the taste for 18th century pieces, he chose mainly 18th century Chinese porcelain: celadon, turquoise blue or Chinese blue ground, evocative of pieces made in the Louis XVI period. Some porcelains were decorated in relief, others with flowers, sometimes with incised ornamentation. The choice of these porcelains, their quality as well as the quality of the gilt bronze mounts, explain why these vases are confused with ancient works. Also from the 19th century, as Alfred de Champeaux reports in his Dictionnaire des fondeurs: "Large Chinese porcelain vases mounted in gilt bronze were made in the workshop of Mr. Beurdeley [...] some of which were sold as old pieces” (1886, p. 120). One of the most famous cases was the celadon porcelain vase, which is now preserved at Waddesdon Manor (WI/59/4). Beurdeley Fils himself wrote of the celadon pieces he created: “They will one day be of great value. My name will be replaced by that of a man from the 18th century, but the work will have been done in 1879 and 80” (Letter to A. de Champeaux, 1886, A.MAD X49).

Personal Collections

The contents of Alfred Beurdeley père’s collections testify to an assimilation between commerce and personal taste. After his death on November 29, 1882 and according to the will of his son, his collection was dispersed during two sales, which took place at the Hôtel Drouot (April 9-10 and April 23-25, 1883). Its collections were divided between two large sets which perfectly reflect the orientation of their trade: curiosities, works of art from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and objects from the 18th century, including the Chinese porcelains which represented about 30 lots, less numerous than European porcelains. Already, his participation in the "Musée oriental” exhibition organised by the Union centrale in 1869 was modest, as he only presented a pair of bronze figurines, compared to Mrs. Malinet, a specialised dealer who presented nearly 150 pieces of porcelain and whose collection had already been published by Albert Jacquemart (1862).

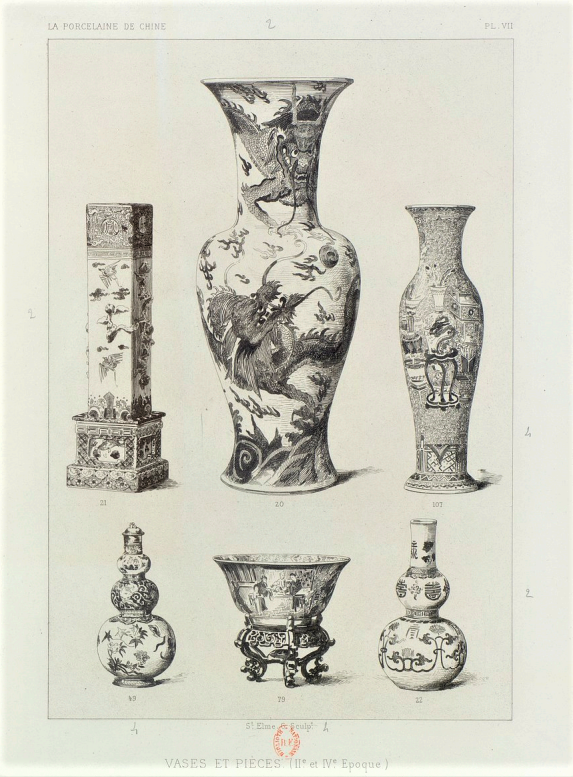

Unlike his father, Alfred Beurdeley Fils devoted a large part of his personal collection to Asian, primarily Chinese, porcelain. Mention was made of this collection at the time of his marriage in 1882 (Marriage contract with Charlotte Portier AN/MC/ETCII). Then aged 35, he owned a collection of "objects from China and Japan" estimated at 80,000 francs and a collection of ornamental drawings, prints, and art books worth 150,000 Francs. 20 years later, following the death of his wife, the collection of "objects from China and Japan" was inventoried by the expert Charles Mannheim and revalued at 371,390 Francs, a considerable increase certainly due to the increasing values and expanding the collection in the meantime. The inventory lists 797 pieces from China and about ten pieces from Japan. The collection consists of various forms of porcelain pieces, from the 16th to the beginning of the 19th century (periods of the Ming and Qing dynasties): snuffboxes, dishes, plates, bowls, cups, teapots, vases, bottles, vases, incense burners, figurines, etc. Some pieces, among the most expensive, were listed as coming from the Marquis sale (Hôtel Drouot, February 12-15, 1883), where Alfred Beurdeley Fils acquired around 20 lots and several contemporary collectors, such as Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), also made purchases. Other pieces, among the oldest, are listed and illustrated by Octave du Sartel in his work on Chinese porcelain (1881, Fig. 13-14; Fig. 88; Pl. VII), including a pair of mounted pots, a large bottle, and a large vase from the Ming period.

In 1906, the collection was exhibited in London by Thomas Joseph Larkin (1848-1915), one of London's first expert dealers in Chinese art, in his "Renaissance Galleries" shop, 104 New Bond Street. Larkin published a brochure on this occasion: The Alfred Beurdeley Collection of rare old Chinese porcelain (1906). This exhibition certainly preceded the dispersion of the collection since it was no longer in the possession of Beurdeley at the time of his death in 1919. It is likely that Larkin sold certain pieces to William Hesketh Lever (Lord Leverhulme) or Charles Lang Freer, who were his most important customers. A stoneware vase and a Yongzheng porcelain lantern vase, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum (C.993-1910 and C1457-1910 respectively), were probably purchased by the collector George Salting (1835-1909) who donated them to the museum in 1910.

The place of Asian works of art and in particular Chinese porcelain in the history of the Beurdeley trade and their collections testifies to the evolution of taste, appreciation and expertise of these objects in the second half of the 19th century. Theyparticipated in the continuation of a tradition, inherited from the 18th century, of opening up to shifts in practices,as well as in a more historical and scientific approach reflectinga progressive change in attitude during the 19th century regarding the reception of these objects in the West.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Personne / personne

Personne / personne